The Castle at Heverlee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overzicht Hinder Voor Dienstverlening

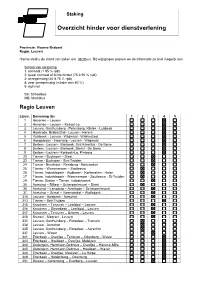

Staking Overzicht hinder voor dienstverlening Provincie: Vlaams-Brabant Regio: Leuven Hierna vindt u de stand van zaken om 06.00uur. Bij wijzigingen passen we de informatie zo snel mogelijk aan. Schaal van verstoring 1: normaal (+ 95 % rijdt) 2: quasi normaal of lichte hinder (75 à 95 % rijdt) 3: onregelmatig (40 à 75 % rijdt) 4: zeer onregelmatig (minder dan 40 %) 5: rijdt niet SB: Schoolbus MB: Marktbus Regio Leuven Lijnnr. Benaming lijn 1 2 3 4 5 1 Heverlee – Leuven 2 Heverlee – Leuven – Kessel-Lo 3 Leuven, Gasthuisberg - Pellenberg, Kliniek - Lubbeek 4 Haasrode, Brabanthal - Leuven - Herent 5 Vaalbeek - Leuven - Wijgmaal - Wakkerzeel 6 Hoegaarden - Neervelp - Leuven - Wijgmaal 7 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Sint-Kamillus - De Borre 8 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Bremt - De Borre 9 Bertem - Leuven - Korbeek-Lo, Pimberg 22 Tienen – Budingen – Diest 23 Tienen - Budingen - Sint-Truiden 24 Tienen - Neerlinter - Ransberg - Kortenaken 25 Tienen – Wommersom – Zoutleeuw 26 Tienen, Industriepark - Budingen - Kortenaken - Halen 27 Tienen, Industriepark - Wommersom - Zoutleeuw - St-Truiden 29 Tienen, Station – Tienen, Industriepark 35 Aarschot – Rillaar – Scherpenheuvel – Diest 36 Aarschot – Langdorp – Averbode – Scherpenheuvel 37 Aarschot – Gijmel – Varenwinkel – Wolfsdonk 310 Leuven - Holsbeek - Aarschot 313 Tienen – Sint-Truiden 315 Kraainem – Tervuren – Leefdaal – Leuven 316 Kraainem – Sterrebeek – Leefdaal – Leuven 317 Kraainem – Tervuren – Bertem – Leuven 318 Brussel - Moorsel - Leuven 333 Leuven, Gasthuisberg – Rotselaar – Tremelo 334 Leuven -

Ons Gazetje Van Juni

Ons Gazetje Uitgever: Senioren KBC kring Leuven Jaargang: 06 Nummer: 06 Datum: 06/2016 Juni: boeren maaien nu hun grasjes, stedelingen pakken hun terrasjes! Vrienden Zal de zomermaand ons effectief terrasjesweer brengen? Mei was koud en nat, zon werd ons niet veel gegund, en toch voltrok zich in de natuur het wonder van ieder jaar. Geuren en kleuren in overvloed! Die schoonheid lokt een mens naar buiten. Een omkadering in vele tinten groen beperkt mijn gezichtsveld, zelfs het huis van onze achterbuur is slechts een dak. Solitair in het midden van het weiland staat een stoere eik in harmonische symbiose van kracht en waardigheid, koning te wezen. In de grasberm langs de gracht bloeit een weelde aan margrieten. Veldbloemen bekoren door hun eenvoud, ze ontplooien zich gaaf en puur zonder een hand die ze beschermt of leidt. Het malse gras van het hooiland is precies op tijd aan maaien toe; in de aangrenzende weiden grazen wit- zwart gevlekte koeien of liggen er urenlang te herkauwen. Een leger bruine konijntjes wipt en rent door de wei waarin de paarden staan, één paard kan dat niet verdragen en gaat furieus achter de langoortjes aan. Enkele dagen geleden is er een veulen geboren, we zagen nog net hoe het op zijn ranke benen leerde staan. Nu volgt het de merrie en vlijt zijn hoofd vertederend tegen moeders hals aan, een prachtig beeld van intimiteit en verbondenheid. In de tuin is het een explosie van rood en wit, lila en roze nu de rododendrons bloeien; prunus en blauwe regen lokken je met een fijn parfum dichterbij. -

Jaar Verslag

JAAR VERSLAG 2020 INHOUD WOORD VOORAF ...................................................................................................... 5 01 OPERATIONEEL EN REGLEMENTAIR KADER .............................................................7 1. Juridisch kader ........................................................................................... 9 2. Verruimde opdracht ................................................................................... 9 3. Interne financieringsfondsen ......................................................................10 4. Personeel .................................................................................................10 5. Verankering binnen de provincie ..................................................................10 6. Relevante ontwikkelingen ...........................................................................10 02 WOONOPDRACHT ............................................................................................... 13 1. Opdracht .................................................................................................. 15 2. Grondbeleid ............................................................................................. 16 2.1 Prospectie .....................................................................................17 2.2 Aankopen 2020 ..............................................................................17 2.3 Verkopen 2020 ..............................................................................17 2.4 Gronden in eigendom .................................................................... -

Carte Du Reseau Netkaart

AMSTERDAM ROTTERDAM ROTTERDAM ROOSENDAAL Essen 4 ESSEN Hoogstraten Baarle-Hertog I-AM.A22 12 ANTWERPEN Ravels -OOST Wildert Kalmthout KALMTHOUT Wuustwezel Kijkuit Merksplas NOORDERKEMPEN Rijkevorsel HEIDE Zweedse I-AM.A21 ANTW. Kapellen Kaai KNOKKE AREA Turnhout Zeebrugge-Strand 51A/1 202 Duinbergen -NOORD Arendonk ZEEBRUGGE-VORMING HEIST 12 TURNHOUT ZEEBRUGGE-DORP TERNEUZEN Brasschaat Brecht North-East BLANKENBERGE 51A 51B Knokke-Heist KAPELLEN Zwankendamme Oud-Turnhout Blankenberge Lissewege Vosselaar 51 202B Beerse EINDHOVEN Y. Ter Doest Y. Eivoorde Y.. Pelikaan Sint-Laureins Retie Y. Blauwe Toren 4 Malle Hamont-Achel Y. Dudzele 29 De Haan Schoten Schilde Zoersel CARTE DU RESEAU Zuienkerke Hamont Y. Blauwe Toren Damme VENLO Bredene I-AM.A32 Lille Kasterlee Dessel Lommel-Maatheide Neerpelt 19 Tielen Budel WEERT 51 GENT- Wijnegem I-AM.A23 Overpelt OOSTENDE 50F 202A 273 Lommel SAS-VAN-GENT Sint-Gillis-Waas MECHELEN NEERPELT Brugge-Sint-Pieters ZEEHAVEN LOMMEL Overpelt ROERMOND Stekene Mol Oostende ANTWERPEN Zandhoven Vorselaar 50A Eeklo Zelzate 19 Overpelt- NETKAART Wommelgem Kaprijke Assenede ZELZATE Herentals MOL Bocholt BRUGGE Borsbeek Grobbendonk Y. Kruisberg BALEN- Werkplaatsen Oudenburg Jabbeke Wachtebeke Moerbeke Ranst 50A/5 Maldegem EEKLO HERENTALS kp. 40.620 WERKPLAATSEN Brugge kp. 7.740 Olen Gent Boechout Wolfstee 15 GEEL Y. Oostkamp Waarschoot SINT-NIKLAAS Bouwel Balen I-AM.A34 Boechout NIJLEN Y. Albertkanaal Kinrooi Middelkerke OOSTKAMP Evergem GENT-NOORD Sint-Niklaas 58 15 Kessel Olen Geel 15 Gistel Waarschoot 55 219 15 Balen BRUGGE 204 Belsele 59 Hove Hechtel-Eksel Bree Beernem Sinaai LIER Nijlen Herenthout Peer Nieuwpoort Y. Nazareth Ichtegem Zedelgem BEERNEM Knesselare Y. Lint ZEDELGEM Zomergem 207 Meerhout Schelle Aartselaar Lint Koksijde Oostkamp Waasmunster Temse TEMSE Schelle KONTICH-LINT Y. -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

Lijst Erkende Inrichtingen Afdeling 0

Lijst erkende inrichtingen 1/09/21 Afdeling 0: Inrichting algemene activiteiten Erkenningnr. Benaming Adres Categorie Neven activiteit Diersoort Opmerkingen KF1 Amnimeat B.V.B.A. Rue Ropsy Chaudron 24 b 5 CS CP, PP 1070 Anderlecht KF10 Eurofrost NV Izegemsestraat(Heu) 412 CS 8501 Heule KF100 BARIAS Ter Biest 15 CS FFPP, PP 8800 Roeselare KF1001 Calibra Moorseelsesteenweg 228 CS CP, MP, MSM 8800 Roeselare KF100104 LA MAREE HAUTE Quai de Mariemont 38 CS 1080 Molenbeek-Saint-Jean KF100109 maatWERKbedrijf BWB Nijverheidsstraat 15 b 2 CS RW 1840 Londerzeel KF100109 maatWERKbedrijf BWB Nijverheidsstraat 15 b 2 RW CS 1840 Londerzeel KF100159 LA BOUCHERIE SA Rue Bollinckx 45 CS CP, MP, PP 1070 Anderlecht KF100210 H.G.C.-HANOS Herkenrodesingel 81 CS CC, PP, CP, FFPP, MP 3500 Hasselt KF100210 Van der Zee België BVBA Herkenrodesingel 81 CS CP, MP 3500 Hasselt KF100227 CARDON LOGISTIQUE Rue du Mont des Carliers(BL) S/N CS 7522 Tournai KF100350 HUIS PATRICK Ambachtenstraat(LUB) 7 CS FFPP, RW 3210 Lubbeek KF100350 HUIS PATRICK Ambachtenstraat(LUB) 7 RW CS, FFPP 3210 Lubbeek KF100378 Lineage Ieper BVBA Bargiestraat 5 CS 8900 Ieper KF100398 BOURGONJON Nijverheidskaai 18 b B CS CP, MP, RW 9040 Gent KF100398 BOURGONJON Nijverheidskaai 18 b B RW CP, CS, MP 9040 Gent KF1004 PLUKON MOUSCRON Avenue de l'Eau Vive(L) 5 CS CP, SH 7700 Mouscron/Moeskroen 1 / 196 Lijst erkende inrichtingen 1/09/21 Afdeling 0: Inrichting algemene activiteiten Erkenningnr. Benaming Adres Categorie Neven activiteit Diersoort Opmerkingen KF100590 D.S. PRODUKTEN Hoeikensstraat 5 b 107 -

Acquisition of the Oase Aarschot Wissenstraat Site

PRESS RELEASE Regulated information 10 July 2014 – After closing of markets Under embargo until 17:40 CET Press release Acquisition of the Oase Aarschot Wissenstraat site Aedifica is pleased to announce the acquisition1 of 100 % of the shares of the BVBA Woon & Zorg Vg Aarschot on 10 July 2014. Woon & Zorg Vg Aarschot is the current owner of a plot of land and buildings in Aarschot (Wissenstraat) and was a subsidiary of the B&R group. This transaction is a part of the agreement in principle (announced on 12 June2) for the acquisition of a portfolio of five rest homes in the province of Flemish Brabant in partnership with Oase and B&R. The site in Aarschot (Wissenstraat)3 is well located in a residential area close to the city centre, approx. 20 kilometres from Leuven. The site was completed in June and recently became operational. It comprises 164 units, of which a rest home of 120 beds and an assisted-living complex of 44 apartments. Both buildings are connected underground and by an aboveground pedway. The rest home is operated by a non-profit organisation of the Oase group, on the basis of a triple net long lease of 27 years, which generates an initial triple net yield of approx. 6 %. The Oase Group operates the assisted-living apartments under an agreement for the right of use with a duration of 27 years. Aedifica may consider selling these assisted-living apartments to third parties in the short term, since they are in this transaction considered by the Company as nonstrategic assets. -

Serviceflats En Assistentiewoningen in Vlaams-Brabant (PDF)

Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid Afdeling Woonzorg Koning Albert II-laan 35 bus 33, 1030 Brussel Tel. 02-553 35 09 Adressen serviceflats en groepen van assistentiewoningen Provincie Vlaams-Brabant AARSCHOT Dossiernr.: 201.201 Erkenningsnr.: CE1882 Gesloten Hof Beheersinstantie Statiestraat 3 OCMW Openbaar Centrum voor 3200 Aarschot Maatschappelijk Welzijn van Aarschot tel. : 016 55 08 38 Ten Drossaarde 1 fax: 016 57 22 92 3200 Aarschot e-mail: [email protected] url: www.ocmw-aarschot.be Erkende capaciteit: 24 Einddatum: Onbepaalde duur Dossiernr.: 201.203 Erkenningsnr.: PE2955 Residentie Demerhof Beheersinstantie Wissenstraat 20 3200 Aarschot CVBA VULPIA VLAANDEREN tel. : 016 26 96 00 Ruiterijschool 6 fax: 2930 Brasschaat e-mail: [email protected] url: www.vulpia.be Erkende capaciteit: 44 Einddatum: Onbepaalde duur Pagina 2 van 79 22-sep-2021 Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid Afdeling Woonzorg Koning Albert II-laan 35 bus 33, 1030 Brussel Tel. 02-553 35 09 Dossiernr.: 201.204 Erkenningsnr.: CE3121 Orleanshof Beheersinstantie Leuvensestraat 148 OCMW Openbaar Centrum voor 3200 Aarschot Maatschappelijk Welzijn van Aarschot tel. : 016 48 24 40 Ten Drossaarde 1 fax: 3200 Aarschot e-mail: [email protected] url: www.ocmw-aarschot.be Erkende capaciteit: 35 Einddatum: Onbepaalde duur Dossiernr.: 201.207 Erkenningsnr.: PE3080 Residentie De Laak Beheersinstantie Mathildelaan 2 - 4 3200 Aarschot VZW RESIDENTIE DE LAAK tel. : 016 26 96 08 Ruiterijschool 6 fax: 2930 Brasschaat e-mail: [email protected] url: www.vulpia.be Erkende capaciteit: 48 Einddatum: Onbepaalde duur Dossiernr.: 201.208 Erkenningsnr.: PE3115 Poortvelde Beheersinstantie Jan Hammeneckerlaan 4 A 3200 Aarschot CVBA VULPIA VLAANDEREN tel. -

Baanrotsen in Brabant

KU Leuven Faculty of Arts Blijde Inkomststraat 21 box 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË Baanrotsen in Brabant Title, power and nobility in the duchy of Brabant in the long fourteenth century Sarah De Decker Presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Advanced Master of Arts in Medieval and Renaissance Studies Supervisor: prof. dr. Hans Cools Academic year 2014-2015 164 096 characters ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In comparison to my dear friends and colleagues from the Advanced Master, it took me some time longer to finish my thesis. The main reason for this was the uncertainty that prevailed at the beginning of this research concerning the question whether I could find baanrotsen in sources for the thirteenth and fourteenth century other than the chronicle of Jan van Heelu. Every time this uncertainty came up, it was met with the positive and motivating spirit of my supervisor prof. dr. Hans Cools. For his patience with me these last two years, for his constant support and for all the encouraging discussions about baanrotsen and Brabant, I would like to sincerely thank him. The completion of this thesis would also never have been realised without the support of my family and friends. To my aunt in particular, Tante Mie, I owe special thanks. She always made time to scrutinize the spelling and grammar of this entire thesis and in doing so, she ensured that I did not had to be embarrassed about my English writing. I would also like to thank my best friends Marjon and Lies, my sister, for the reading, their support and all the hours they sacrificed to listening to all my thoughts and concerns. -

Bibliotheeknet Vlaams-Brabant

Bibliotheeknet Vlaams-Brabant Raadpleeg de online catalogus van Bibliotheeknet Vlaams-Brabant In welke bibliotheken kan je terecht met een lidkaart van Bibliotheeknet Vlaams-Brabant? Bibliotheek Asse Bibliotheek Beersel catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Bertem Bibliotheek Bierbeek catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Diest Bibliotheek Dilbeek catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Galmaarden Bibliotheek Geetbets catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Glabbeek Bibliotheek Gooik catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Grimbergen Bibliotheek Halle catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Herent Bibliotheek Herne catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Huldenberg Bibliotheek Kapelle-op-den-Bos catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Keerbergen Bibliotheek Kortenaken catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Kortenberg Bibliotheek Lennik catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Leuven Bibliotheek Linter catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Londerzeel Bibliotheek Machelen catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Meise Bibliotheek Merchtem catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Opwijk Bibliotheek Oud-Heverlee catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Pepingen Bibliotheek Roosdaal catalogus - contact catalogus - contact Bibliotheek Rotselaar Bibliotheek -

"Demervallei Tussen Aarschot En Diest" in Aarschot, Diest En Scherpenheuvel-Zichem

/,. I J : J, , ' I I Vlaamse Regering ~l~ • )~ - Ministerieel besluit tot definitieve aanduiding van de ankerplaats "Demervallei tussen Aarschot en Diest" in Aarschot, Diest en Scherpenheuvel-Zichem DE VLAAMSE MINISTER VAN BESTUURSZAKEN, BINNENLANDS BESTUUR, INBURGERING, TOERISME EN VLAAMSE RAND, Gelet op het decreet van 16 april 1996 betreffende de landschapszorg, gewijzigd bij de decreten van 21 oktober 1997, 18 mei 1999, 8 december 2000, 21 december 2001, 19 juli 2002, 13 februari 2004, 10 maart 2006, 16 juni 2006 en 27 maart 2009; Gelet op het besluit van de Vlaamse Regering van 13 juli 2009 tot bepaling van de bevoegdheden van de leden van de Vlaamse Regering, gewijzigd bij besluiten van 24 juli 2009, 4 december 2009, 6 juli 2010 en 7 juli 2010, 24 september 2010, 19 november 2010, 13 mei 2011, 10 juni 2011, 9 september 2011 en 14 oktober 2011; Gelet op het ministerieel besluit van 13 maart 2013 tot voorlopige aanduiding van de ankerplaats Demervallei tussen Aarschot en Diest; Gelet op het advies van de Koninklijke Commissie voor Monumenten en Landschappen van 21 november 2013, BESLUIT: Artikel 1. "Demervallei tussen Aarschot en Diest" in Aarschot, Diest en Scherpenheuvel-Zichem wordt definitief aangeduid als ankerplaats overeenkomstig de bepalingen van het decreet van 16 april 1996 betreffende de landschapszorg, gewijzigd bij de decreten van 21 oktober 1997, 18 mei 1999, 8 december 2000, 21 december 2001, 19 juli 2002, 13 februari 2004, 10 maart 2006, 16 juni 2006 en 27 maart 2009. Art. 2. § 1. Het algemeen belang dat de aanduiding verantwoordt, wordt door het gezamenlijk voorkomen en de onderlinge samenhang van de volgende intrinsieke waarden gemotiveerd: ./ . -

Startersgids VLAA M S -B RA B ANT

V.U: FRANÇOIS DE VLEESCHOUWER - PLATANENLAAN 9 - 2200 HERENTALS // ECD MEMO VLAAMS-BRABANT - WINGERDSTRAAT 14 - 3000 LEUVEN Familiegroepen P Jongdementie ROVINCIE Dementie & Dementie Programma’s 2020 Programma’s Startersgids VLAA M S Jongdementie -B Dementie & Dementie Praatcafés RA B ANT Overzicht Familiegroepen Dementie en Jongdementie en Praatcafés (Jong)Dementie in de provincie Vlaams-Brabant: Praatcafés Dementie: Aarschot, Asse, Beersel, Bertem/Herent, Bierbeek, Buizingen, Druivenstreek, Grimbergen/Kapelle-op-den-bos/Londerzeel/Wol- vertem/Meise, Haacht, Halle, Heikruis, Holsbeek, Kampenhout, Leuven, Rotselaar, Sint-Pieters-Leeuw, Tielt-Winge, Tienen, Zaventem, Zemst en Zoutleeuw Familiegroepen Dementie: Aarschot, Dilbeek, Grimbergen, Londerzeel Jongdementie, Pajotten- land (Heikruis), Steenokkerzeel-Melsbroek-Perk en Tienen 2 Wat is een Praatcafé Dementie? • Informatiemoment over dementie • Vast programma met gastdeskundige rond een vooraf bepaald thema • Nadien gelegenheid tot vragen stellen en ervaringen uitwisselen • Voor familieleden van personen met dementie en andere geïnteresseerden • Gratis, zonder inschrijven Waarvoor kan je bij regionaal Expertisecentrum Dementie Memo (ECD Memo) terecht? • Informatie- en adviesvragen • Ondersteuning en doorverwijzing • Voor actuele informatie uit uw regio zoals: o Vorming- en opledingsaanbod o Overlegplatform dementie o Sociale kaart dementie o … www.dementie.be/memo Memo 3 Wat is een Familiegroep Dementie en Jongdementie? • Lotgenotencontact • Ervaringen, tips en steun uitwisselen • Voor