9MB-Snow-Leopards-New-Friend.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

Surveys at a Tibetan Antelope Pantholops Hodgsonii Calving Ground Adjacent to the Arjinshan Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, China: Decline and Recovery of a Population

Surveys at a Tibetan antelope Pantholops hodgsonii calving ground adjacent to the Arjinshan Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, China: decline and recovery of a population W illiamV.Bleisch,PaulJ.Buzzard,HuibinZ hang,DonghuaX U¨ ,ZhihuL iu W eidong L i and H owman W ong Abstract Females in most populations of chiru or Tibetan Leslie & Schaller, 2008). Despite the remoteness of chiru antelope Pantholops hodgsonii migrate each year up to 350 km habitat, however, there was an upsurge in poaching during to summer calving grounds, and these migrations charac- the 1980s and 1990s for its extraordinarily fine wool known terize the Tibet/Qinghai Plateau. We studied the migratory as shahtoosh (Wright & Kumar, 1998). Poaching raised the chiru population at the Ullughusu calving grounds south- threat of extirpation for many chiru populations (Harris west of the Arjinshan Nature Reserve in Xinjiang, China. et al., 1999; Bleisch et al., 2004; Fauna & Flora International, 2 The 750–1,000 km of suitable habitat at Ullughusu is at 2004). Competition with livestock for grazing has been and 4,500–5,000 m with sparse vegetation. We used direct meth- continues to be a threat and, more recently, infrastructure ods (block counts, vehicle and walking transects and radial development, fencing of pasture and gold mining have point sampling) and an indirect method (pellet counts) become increasing problems (Bleisch et al., 2004; Fauna & during six summers to assess population density. We also Flora International, 2004; Xia et al., 2007; Fox et al., 2009). witnessed and stopped two major poaching events, in 1998 Chiru are categorized on the IUCN Red List as Endangered and 1999 (103 and 909 carcasses, respectively). -

Of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet

RANGELANDS 18(3), June 1996 91 Rangelands of the Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve in Tibet Daniel J. Millerand George B. Schaller eastern part of the cious steppes and mountains that Chang Tang Reserve sweep along northern Tibet for almost based on our research in 800 miles east to west. The chang the fall of 1993 and sum- tang, a vast and vigorous landscape mer of 1994. We also comparable in size to the Great Plains discuss conservation of North America, is one of the highest, issues facing the reserve most remote and least known range- and the implications lands of the world. The land is too cold these have for develop- and arid to support forests and agricul- ment, management and ture; vegetation is dominated by cold- conservation. desert grasslands,with a sparse cover of grasses, sedges, forbs and low shrubs. It is one of the world's last Descriptionand great wildernessareas. Location The Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve was established by the Tibetan Located in the north- Autonomous governmentin of the Region western part 1993 to protect Tibet's last, major Tibetan Autonomous wildlife populationsand the grasslands Region (see Map 1), the depend upon. In the wildernessof Reserve they Chang Tang the Chang Tang Reservelarge herdsof encompasses approxi- Tibetan antelope still follow ancient mately 110,000 square trails on their annual migrationroutes to A nomad bundled the wind while Tibetan lady up against miles, (an area about birthing grounds in the far north. Wild herding. of the size Arizona), yaks, exterminated in most of Tibet, and is the second in maintain their last stronghold in the he Chang Tang Wildlife Reserve, area in the world. -

Identification Guidelines for Shahtoosh & Pashmina

Shahtoosh (aka Shah tush) is the trade name for woolen garments, usually shawls, made from the hair of the Tibetan antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii). Also called a chiru, it is considered an endangered species, and the importation of any part or product of Pantholops is prohib- ited by U.S. law. Chiru originate in the high Himalaya Mountains of Tibet, western China, and far northern India where they are killed for their parts. Their pelts are converted into shahtoosh, and horns of the males are taken as trophies. No chirus are kept in captivity, and it reportedly takes three to five individuals to make a single shawl (Wright & Kumar 1997). Trophy Head with Horns of male Pantholops hodgsonii SHAWL COLORS Off-white and brownish beige are the natural colors of the chiru’s pelage. Shahtoosh shawls in these natural colors are the most traditional. How- ever, shahtoosh can be dyed almost any color of the spectrum. Unless the fibers are dyed opaque black, most dyed fibers allow the transmission of light so that the internal characteristics are visible under a compound microscope. (See "Microscopic Characteristics" in Hints for Visual Identification.) DIFFERENT PATTERNS AND/OR DECORATION SIZES - Solid color - Standard shawl 36" x 81" - Plaid - Muffler 12" x 60" - Stripes - Man-size, Blanket 108" x 54" - Edged in wispy fringe - Couturier length (4' x 18' +) - Double color (each side of shawl is a different color) - All-over embroidery APPROXIMATE PRICE RANGES Cost Wholesale Retail Plain $550-$1,000 $700-$2,500 $1,500-$2,450 Pastels $700-$850 $1,300-$2,600 $1,800-$3,000 Checks/Plaids $600-$1,500 $800-$1,180 $1,300-$2,450 Stripe $600-$800 $1,300-$1,800 $2,450-$3,200 Double color $800-$1,000 $1,380-$2,800 $2,100-$3,200 Border embroidery $850-$3,050 $1,080-$1,600 $1,500-$3,200 All-over embroidery $800-$5,000 $1,380-$5,500 $3,000-$6,500 White $1,800 $2,300 $4,600 Above prices are for standard size shawls in year 2000. -

Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Chapter 92A)

1 S 23/2005 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 11th January 2005 at 5:00 pm. NO.S 23 ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (CHAPTER 92A) ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (AMENDMENT OF FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD SCHEDULES) NOTIFICATION 2005 In exercise of the powers conferred by section 23 of the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act, the Minister for National Development hereby makes the following Notification: Citation and commencement 1. This Notification may be cited as the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Amendment of First, Second and Third Schedules) Notification 2005 and shall come into operation on 12th January 2005. Deletion and substitution of First, Second and Third Schedules 2. The First, Second and Third Schedules to the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act are deleted and the following Schedules substituted therefor: ‘‘FIRST SCHEDULE S 23/2005 Section 2 (1) SCHEDULED ANIMALS PART I SPECIES LISTED IN APPENDIX I AND II OF CITES In this Schedule, species of an order, family, sub-family or genus means all the species of that order, family, sub-family or genus. First column Second column Third column Common name for information only CHORDATA MAMMALIA MONOTREMATA 2 Tachyglossidae Zaglossus spp. New Guinea Long-nosed Spiny Anteaters DASYUROMORPHIA Dasyuridae Sminthopsis longicaudata Long-tailed Dunnart or Long-tailed Sminthopsis Sminthopsis psammophila Sandhill Dunnart or Sandhill Sminthopsis Thylacinidae Thylacinus cynocephalus Thylacine or Tasmanian Wolf PERAMELEMORPHIA -

GNUSLETTER Vol 37#2.Pdf

GNUSLETTER Volume 37 / Number 2 December 2020 ANTELOPE SPECIALIST GROUP IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group GNUSLETTER is the biannual newsletter of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Antelope Specialist Group (ASG). First published in 1982 by first ASG Chair Richard D. Estes, the intent of GNUSLETTER, then and today, is the dissemination of reports and information regarding antelopes and their conservation. ASG Members are an important network of individuals and experts working across disciplines throughout Africa, Asia and America. Contributions (original articles, field notes, other material relevant to antelope biology, ecology, and conservation) are welcomed and should be sent to the editor. Today GNUSLETTER is published in English in electronic form and distributed widely to members and non-members, and to the IUCN SSC global conservation network. To be added to the distribution list please contact [email protected]. GNUSLETTER Editorial Board - David Mallon, ASG Co-Chair - Philippe Chardonnet, ASG Co-Chair ASG Program Office - Tania Gilbert, Marwell Wildife The Antelope Specialist Group Program Office is hosted and supported by Marwell Wildlife https://www.marwell.org.uk The designation of geographical entities in this report does not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of IUCN, the Species Survival Commission, or the Antelope Specialist Group concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or concerning the delimitation of any frontiers or boundaries. Views expressed in GNUSLETTER are those of the individual authors, Cover photo: Young female bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), W National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Niger (© Daniel Cornélis) 2 GNUSLETTER Volume 37 Number 2 December 2020 FROM IUCN AND ASG………………………………………………………. -

Fa Sh Io N Ed Fo R Ex Tin Ctio N

FA SH IO N ED FO R EX T IN C T IO N W PSI S - 25 P a n ch sh ee l P a rk , N ew D e lh i – 110 0 17, In d ia w w w .w p si- in d ia .o rg FA SH IO N ED FO R EX T IN C T IO N W PSI S - 25 P a n ch sh ee l P a rk , N ew D e lh i – 110 0 17, In d ia w w w .w p si- in d ia .o rg FA SH IO N ED FO R EX T IN C T IO N W PSI Fashioned for Extinction An Exposé of the Shahtoosh Trade Foreword The herd of Tibetan antelope or chiru poured over a ridge and headed past the turquoise waters of Luotuo Hu, Camel Lake, towards the glacier-capped peaks of the Aru Range. I watched the animals pass, two thousand of them, all females with their month-old young, migrating south in late July after giving birth in the bleak uplands somewhere in north-western Tibet. Here at 16,500 feet (5,000 m), I saw a last vestige of the past when chirus roamed the Chang Tang (meaning Northern Plain in Tibetan) in many hundreds of thousands. British explorers around the turn of the century marveled at the sight of twenty thousand or more chirus dotting the steppe before them. The chiru is confined to the Tibetan Plateau of China, except for a few animals which seasonally enter the Ladakh area of India. -

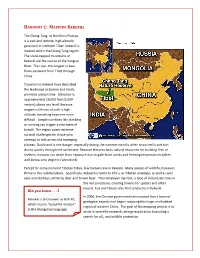

Kekexili Student Activity Booklet

HANDOUT 1: MAPPING KEKEXILI The Chang Tang, or Northern Plateau, is a vast and remote, high altitude grassland in northern Tibet. Kekexili is located within the Chang Tang region. The snow‐capped mountains of Kekexili are the source of the Yangtze River. The river, the longest in Asia, flows eastward from Tibet through China. Travelers to Kekexili have described the landscape as barren and harsh, primitive and pristine. Elevation is approximately 16,000 feet (5,000 meters) above sea level. Because oxygen is thinner at such a high altitude, breathing becomes more difficult. Simple exertions like climbing or running can trigger a shortness of breath. The region poses extreme survival challenges for those who attempt to trek across the sweeping plateau. Quicksand is one danger, especially during the summer months when snow melts and rain drains quickly through the sandstone. Because the area lacks natural resources for building fires or shelters, humans risk death from exposure due to gale‐force winds and freezing temperatures (often well below zero degrees Fahrenheit). Except for some nomadic Tibetan tribes, few humans live in Kekexili. Many species of wildlife, however, thrive in this isolated place. Specifically, Kekexili is home to Chiru, or Tibetan antelope, as well as wild yaks and donkeys, white lip deer and brown bear. The Himalayan marmot, a type of rodent, burrows in the red sandstone, creating havens for spiders and other insects. Fox and falcons also find sanctuary in Kekexili. Did you know . .? In 2006, the Chinese government announced that a team of Kekexili is also known as Hoh Xil, geological experts had begun mapping this large uninhabited which means “beautiful maiden” region of western China. -

Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION RECOGNITION The family Bovidae, which includes Antelopes, Cattle, Duikers, Gazelles, Goats, and Sheep, is the largest family within Artiodactyla and the most diverse family of ungulates, with more than 270 recent species. Their common characteristic is their unbranched, non-deciduous horns. Bovids are primarily Old World in their distribution, although a few species are found in North America. The name antelope is often used to describe many members of this family, but it is not a definable, taxonomically based term. Shape, size, and color: Bovids encompass an extremely wide size range, from the minuscule Royal Antelope and the Dik-diks, weighing as little as 2 kg and standing 25 to 35 cm at the shoulder, to the Asian Wild Water Buffalo, which weighs as much as 1,200 kg, and the Gaur, which measures up to 220 cm at the shoulder. Body shape varies from relatively small, slender-limbed, and thin-necked species such as the Gazelles to the massive, stocky wild cattle (fig. 1). The forequarters may be larger than the hind, or the reverse, as in smaller species inhabiting dense tropical forests (e.g., Duikers). There is also a great variety in body coloration, although most species are some shade of brown. It can consist of a solid shade, or a patterned pelage. Antelopes that rely on concealment to avoid predators are cryptically colored. The stripes and blotches seen on the hides of Bushbuck, Bongo, and Kudu also function as camouflage by helping to disrupt the animals’ outline. -

Gnusletter October2014 II.Indd

Volume 32 Number 1 ANTELOPE SPECIALIST GROUP October 2014 GNUSLETTER VOL. 31 NO. 1 In this Issue... From the Gnusletter Editor • This issue: S. Shurter Reports and Projects • “Five Minutes to Midnight” for Arabian gazelles in Harrat, Uwayrid, northwestern Saudi Arabia. T. Wron- ski, T. Butynski • Have protected areas failed to conserve Nilgai in Nepal? Hem Sagar Baral • Large mammals back to the Gile’ National Reserve, Mozambique. A. Fusari, J. Dias, C.L. Pereira, H. Bou- let, E. Bedin, P. Chardonnet • Status of Hirola in Ishaqbini Community Conservancy. J. King, I. Craig, M. Golicha, M.I. Sheikh, S. Leso- wapir, D. Letoiye, D. Lesimirdana, J. Worden Meetings and Updates • Dama Gazelle Workshop, H. Senn Recent Publications • Historical incidence of springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) in the northeastern Cape: J.M. Feely. South African Journal of Wildlife Research • A Retrospective Evaluation of the Global Decline of Carnivores and Ungulates. M. DiMarco, L. Boitani, D.Mallon, M. Hoffman, A. Iacucci, E. Meijaard, P. Visconti, J. Schipper, C. Rondinini. Conservation Biol- ogy • Just another island dwarf? Phenotypic distinctiveness in the poorly known Soemmerring’s Gazelle, Nanger soemmerringi of Dahlak Kebir Island. G. Chiozzi, G. Bardelli, M. Ricci, G. DeMarchi, A. Cardini. Biologi- cal Journal of the Linnean Society • Response to “ Are there really twice as many bovid species as we thought?” F.P.D. Cotterill, P.J.Taylor, S. Gippoliti, J.M. Bishop, C. Groves. Systematic Biology Antelope News • CITES Notifi cation to the Parties – Tibetan Antelope ISSN 2304-0718 page 6 GNUSLETTER VOL. 31302932 NO. 1 From the Gnusletter Editor... presence of Arabian gazelles has not been confi rmed at any of the north-western sites since before 2002 and, for most sites, not since Antelope aren’t on the news forefront in this age of social media the mid-1990s. -

Tibetan Antelope and New Rangeland Management Activities in and Around the Aru Basin, Chang Tang Nature Reserve

Report to the Tibet Autonomous Region Forestry Bureau Tibetan antelope and new rangeland management activities in and around the Aru Basin, Chang Tang Nature Reserve Joseph L. Fox Kelsang Dhondup Tsechoe Dorji 5 February 2008 Report to the Tibet Autonomous Region Forestry Bureau Tibetan antelope and new rangeland management activities in and around the Aru Basin, Chang Tang Nature Reserve University of Tromsø, Norway research program, in cooperation with agencies in the Tibet Autonomous Region: 1999-2007 5 February 2008 Joseph L. Fox1, Kelsang Dhondup2,1 and Tsechoe Dorji 3,1 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Tromsø, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway [email protected] 2Tibet Academy Agricultural and Animal Science, Jin Zhu Rd. No. 130, Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 860000, China [email protected] 3Department of Plant Science and Technology, College of Agriculture and Animal Husbandry, Tibet University, College Rd. No. 8, Bayi Township, Nyingchi District, Tibet Autonomous Region 860000, China [email protected] Executive summary Based on wildlife and human resource use research in the western Chang Tang Nature Reserve conducted over the past eight years, we report on new policy initiatives and consequent changes in human use that may strongly and negatively affect conservation goals in the nature reserve. Using our Aru Basin study area in the western reserve, we show how the implementation of standard “household responsibility contract system” and “returning pasture to grassland” policy directives, with some unusual applications in this area of high wildlife abundance, are likely to severely affect the populations of several large herbivore species in the western reserve, but primarily the endangered Tibetan antelope Pantholops hodgsoni.