SIT Digital Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Traffic Survey and Traffic Demand Forecast

Final Report – Executive Summary The Study on Greater Kampala Road Network and Transport Improvement in the Republic of Uganda November 2010 CHAPTER 5 TRAFFIC SURVEY AND TRAFFIC DEMAND FORECAST 5.1 TRAFFIC SURVEY The Study Team conducted a traffic survey in January 2010 to identify the current traffic condition and to forecast the future traffic demand. A supplemental traffic survey was also conducted on major junctions in June 2010 to study the current intersection condition and problems. The objective, method and coverage of six types of traffic survey are summarized as below: Table 5.1.1 Outline of Traffic Survey Survey Objectives Method Coverage To obtain traffic volumes on 12 locations (12hr) Traffic Count Survey Vehicular Traffic Count major roads 2 locations (24hr) Origin-Destination (O-D) To capture trip information of Interview with drivers at 9 locations Survey vehicles roadsides To obtain traffic volumes and Intersection Traffic Count movement at major Vehicular Traffic Count 2 locations Survey intersections To collect information about Taxi (Minibus) Passenger and Interview with taxi public transport driver and 5 major taxi parks Driver Interview Survey drivers and users users, and their opinions Boda-Boda (Bike Taxi) To collect information about Interview with boda-boda 6 areas on major Passenger and Driver boda-boda drivers and users, drivers and users roads Interview Survey and their opinions To collect information on Actual driving survey by Travel Speed Survey present traffic situation on passenger car major roads Source: JICA Study Team Actual traffic survey was conducted from January to February 2010. Each type of survey schedule is shown in below figure: 2009 2010 Survey Dec. -

Handbook on Environmental Law in Uganda

HANDBOOK ON ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN UGANDA Editors: Kenneth Kakuru Volume I Irene Ssekyana HANDBOOK ON ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN UGANDA Volume I If we all did little, we would do much Second Edition February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................... v Forward ........................................................................................................................................................................vi Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION TO ENVIRONMENTAL LAW ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 A Brief History of Environmental Law ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Religious, Cultural and historical roots .................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2 The Green Revolution ............................................................................................................................ 2 1.1.3 Environmental Law in the United States of America -

Vol. CX No. 25 5Th May, 2017

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Registered at the — General Past Officefor transmission within East Africa as a Newspaper Hiettiuedl ty Vol. CX No. 25 5th May, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 yr CONTENTS PAGE General Notice No. 348 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice... ae sais 433 The Companies Act—Notices.. F wise 433 THE COMPANIES ACT, LAWS OF UGANDA,2000. The Electoral Commission Act—Notices ... 434-436 (Cap. 110). The Bank of Uganda Act—Notices_... .. 437-438 The Electricity ‘Act—Notices 439-440 NOTICE. The Trademarks Act— Registration of Applications 440-446 PURSUANT to Section 40(4) of the Companies Act, (No. Advertisements.. w. 446-452 SUPPLEMENTS 1/2012) Laws of Uganda, 2000, notice is hereby given that Statutory Instruments KIKAGATE SERVICE STATION LIMITED,has been by a No. 21—The Non-Governmental Organisations (Fees) special resolution passed on 14th March, 2017, and with the Regulations, 2017. approval of the Registrar of Companies, changed in nameto No. 22—The Non-Governmental Organisations Regulations, EDDIES' SERVICE STATION LIMITED, and that such 2017. No, 23—The Electoral Commission (Appointment of Date of new name has been entered in myRegister. Completion of Update of Voters' Register in Tororo Dated at Kampala, this 15th day of March, 2017. District) Instrument, 2017. AYALO VIVIENNE, CORRIGENDUM Assistant Registrar of Companies. Take notice that General Notice No. 276 of 2017, was erroneously advertised in The Uganda Gazette Vol. CX, No. 20 of 5th April, 2017. The name was wrongly typeset as General Notice No. 349 of 2017. Namusoke Rose instead of NAMUKOSE ROSE, the THE COMPANIES ACT, LAWS OF UGANDA,2000. -

E464 Volume I1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM

E464 Volume i1;Wj9,GALIPROJECT 4 TOMANSMISSIONSYSTEM Public Disclosure Authorized Preparedfor: UGANDA A3 NILE its POWER Richmond;UK Public Disclosure Authorized Fw~~~~I \ If~t;o ,.-, I~~~~~~~ jt .4 ,. 't' . .~ Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: t~ IN),I "%4fr - - tt ?/^ ^ ,s ENVIRONMENTAL 111teinlauloln.al IMPACT i-S(. Illf STATEME- , '. vi (aietlph,t:an,.daw,,, -\S_,,y '\ /., 'cf - , X £/XL March, 2001 - - ' Public Disclosure Authorized _, ,;' m.. .'ILE COPY I U Technical Resettlement Technical Resettlement Appendices and A e i ActionPlan ,Community ApenicsAcinPla Dlevelopment (A' Action Plan (RCDAP') The compilete Bujagali Project EIA consists of 7 documents Note: Thetransmission system documentation is,for the most part, the same as fhat submittedto ihe Ugandcn National EnvironmentalManagement Authority(NEMAI in December 2000. Detailsof the changes made to the documentation betwoon Dccomber 2000 and the presentsubmission aro avoiloblo from AESN P. Only the graphics that have been changed since December, 2000 hove new dates. FILE: DOChUME[NTC ,ART.CD I 3 fOOt'ypnIp, .asod 1!A/SJV L6'.'''''' '' '.' epurf Ut tUISWXS XillJupllD 2UI1SIXg Itb L6 ... NOJIDSaS1J I2EIof (INY SISAlVNV S2IAIlVNTIuaJ bV _ b6.sanl1A Puu O...tp.s.. ZA .6san1r^A pue SD)flSUIa1DJltJJ WemlrnIn S- (7)6. .. .--D)qqnd llH S bf 68 ..............................................................--- - -- io ---QAu ( laimpod u2Vl b,-£ 6L ...................................... -SWulaue lu;DwIa:43Spuel QSI-PUU'l Z btl' 6L .............................................----- * -* -SaULepunog QAfjP.4SlUTtUPad l SL. sUOItllpuo ltUiOUOZg-OioOS V£ ££.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~A2~~~~~~~~~3V s z')J -4IOfJIrN 'Et (OAIOsOa.. Isoa0 joJxxNsU uAWom osILr) 2AX)SO> IsaIo4 TO•LWN ZU£N 9s ... suotll puoD [eOT20olla E SS '' ''''''''..........''...''................................. slotNluolqur wZ S5 ' '' '' '' ' '' '' '' - - - -- -........................- puiN Z'Z'£ j7i.. .U.13 1uu7EF ................... -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00002916 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (IDA-43670) ON A CREDIT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 22.0 MILLION (US$ 33.6 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA FOR A KAMPALA INSTITUTIONAL AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT ADAPTABLE PROGRAM LOAN (APL) PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 27, 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Urban Development & Services Practice 1 (AFTU1) Country Department AFCE1 Africa Region CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective July 31, 2007) Currency Unit = Uganda Shillings (Ushs) Ushs 1.00 = US$ 0.0005 US$ 1.53 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR July 1 – June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS APL Adaptable Program Loan CAS Country Assistance Strategy CRCS Citizens Report Card Surveys CSOs Civil Society Organizations EA Environmental Analysis EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP Environment Management Plan FA Financing Agreement FRAP Financial recovery action plan GAAP Governance Assessment and Action Plan GAC Governance and Anti-corruption GoU Government of Uganda HDM-4 Highway Development and Management Model HR Human Resource ICR Implementation Completion Report IDA International Development Association IPF Investment Project Financing IPPS Integrated Personnel and Payroll System ISM Implementation Support Missions ISR Implementation Supervision Report KCC Kampala City Council KCCA Kampala Capital City Authority KDMP Kampala Drainage Master Plan KIIDP Kampala Institutional and Infrastructure Development Project -

EXAMING POOR DRAINAGE in BWAISE II PARISH, KAWEMPE DIVISION, KAMPALA the Streams in Bwaise II Parish Are No Longer in Their Natural State

2011 Mubiru Katya Paul Written by Sarah Namulondo EXAMING POOR DRAINAGE IN BWAISE II PARISH, KAWEMPE DIVISION, KAMPALA The streams in Bwaise II Parish are no longer in their natural state. They flow in straight courses and carry polluted water. This is because of the various forms of the both direct and indirect human interferences. Changes on the land surface consequent to urbanization constitute an indirect interference. EXAMINING POOR DRAINAGE IN BWAISE II PARISH, KAWEMPE DIVISION, KAMPALA BY MUBIRU KATYA PAUL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE REQUIREMENTS FOR AWARD OF MASTERS DEGREE IN NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT OF NKUMBA UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 2011 2 DECLARATION I, MUBIRU KATYA PAUL, hereby declare that this dissertation is my original work and has never been published or submitted to any university or institution of higher learning for the award of a Post graduate Degree. SIGNED……………………………………………………………………………….. DATE…………………………………………………………………………………… i APPROVAL This dissertation has been produced under my supervision and has been submitted with my approval as the university supervisor for examination and award of Masters of Science degree in Natural Resources Management. Professor Eric Edroma ………………. ..................... SUPERVISOR Signed Date ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to: I. The people who will find my research data useful in helping to implement and cover the gaps of Environmental law, II. The members of my family who have supported me emotionally and financially throughout my academic career, III. My mother and father Mr and Mrs Katya II Difasi (Senior of Nawansenga Iganga District) and my Aunt Hanifa Nadongo Walangira (Bulebi- Bugiri) who sacrificed a lot for my education, and IV. -

Approved Bodaboda Stages

Approved Bodaboda Stages SN Division Parish Stage ID X-Coordinate Y-Coordinate 1 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1001 32.563999 0.317146 2 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1002 32.564999 0.317240 3 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1003 32.566799 0.319574 4 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1004 32.563301 0.320431 5 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1005 32.562698 0.321824 6 CENTRAL DIVISION BUKESA 1006 32.561100 0.324322 7 CENTRAL DIVISION INDUSTRIAL AREA 1007 32.610802 0.312010 8 CENTRAL DIVISION INDUSTRIAL AREA 1008 32.599201 0.314553 9 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1009 32.565701 0.325353 10 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1010 32.569099 0.325794 11 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1011 32.567001 0.327003 12 CENTRAL DIVISION KAGUGUBE 1012 32.571301 0.327249 13 CENTRAL DIVISION KAMWOKYA II 1013 32.583698 0.342530 14 CENTRAL DIVISION KOLOLO I 1014 32.605900 0.326255 15 CENTRAL DIVISION KOLOLO I 1015 32.605400 0.326868 16 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1016 32.567101 0.305112 17 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1017 32.563702 0.306650 18 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1018 32.565899 0.307312 19 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1019 32.567501 0.307867 20 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1020 32.567600 0.307938 21 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1021 32.569500 0.308241 22 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1022 32.569199 0.309950 23 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1023 32.564800 0.310082 24 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1024 32.567600 0.311253 25 CENTRAL DIVISION MENGO 1025 32.566002 0.311941 26 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1026 32.567501 0.314132 27 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1027 32.565701 0.314559 28 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD KAMPALA 1028 32.566002 0.314855 29 CENTRAL DIVISION OLD -

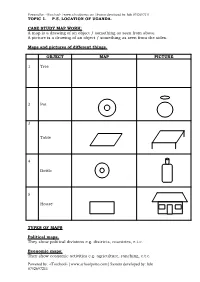

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

Characteristics of Macrophytes in the Lubigi Wetland in Uganda

Vol. 10(10), pp. 394-406, October 2018 DOI: 10.5897/IJBC2018.1206 Article Number: 98C504658827 ISSN: 2141-243X Copyright ©2018 International Journal of Biodiversity and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJBC Conservation Full Length Research Paper Characteristics of macrophytes in the Lubigi Wetland in Uganda John K. Kayima and Aloyce W. Mayo* Department of Water Resources Engineering, University of Dar es Salaam, P. O. Box 35131, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Received 1 July, 2018; Accepted 16 August, 2018 The Lubigi wetland, which is located in the north-western part of Kampala, the capital city of Uganda has been severely strained from anthropogenic encroachment and activities. These activities include harvesting of Cyperus papyrus and other plants, land filling for reclamation, human settlements and disposal of wastewater into the wetland among others. As a result of these anthropogenic activities, the macrophytes diversity and biomass in the wetland have been affected, which in turn affects the effectiveness of wetland for removal of pollutants. It is therefore important to investigate the characteristics of wetland macrophytes in the Lubigi wetland. Pertinent field investigations, surveys, data collection and laboratory tests and analyses were carried out. The problem being addressed was the current lack of information and knowledge about the biomass and biodiversity of the Lubigi wetland to protect the downstream Mayanja River and Lake Kyoga. Three transects each of 1.0 m wide was cut across this zone at about 700 m downstream of the main wastewater inlet, the second at about 1,440 m downstream of the main wastewater inlet and the third at about 1,930 m downstream of the main wastewater inlet. -

3.3 Current Situation and Key Issues of the Public Transport Sector in Gkma

Final Report The Study on Greater Kampala Road Network and Transport Improvement in the Republic of Uganda November 2010 3.3 CURRENT SITUATION AND KEY ISSUES OF THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT SECTOR IN GKMA 3.3.1 OVERVIEW OF THE PUBLIC TRANSPORT The privately owned Uganda Transport Company (UTC) held the exclusive franchise for bus services in Kampala until its nationalization in 1972. At that time, its only competition came from shared taxis which are saloon or estate cars. Following its nationalization, UTC contracted and focused more closely on its long-distance services. As a result, the market for urban transport services in Kampala became open to private sector operators using small minibus vehicles. In 1994 a commercial vehicle distributor established City Link as a private-sector large bus operation with some 40 vehicles in service. However, UTODA was able to organize an effective competition to this initiative. City Link meanwhile did not succeed by operating similar to that of minibus services based on fill-and-run principle, rather than operating based on scheduled services. Thus, the company shortly collapsed. Feedback from these results indicates that although City Link was popular, its operations were too thinly spread over the network and were not able to provide a reliable service. Public transport passengers within Kampala have very limited choice such as minibus services or motorcycle services with the majority as minibus services locally called taxis. 3.3.2 TAXI/MINIBUS Main supply of public transport in Kampala is now by minibuses, which are known locally as taxi (photographs bellow). KCC estimated that in 2003, there were nearly 7,000 minibuses based in the GKMA. -

Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development V1: Vote Overview I

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Ministerial Policy Statement FY 2019/20 Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development V1: Vote Overview I. Vote Mission Statement ³To ensure reliable, adequate and sustainable exploitation, management and utilization of energy and mineral resources for the inclusion and benefit of all people in Uganda´ II. Strategic Objective a. To meet the energy needs of Uganda's population for social and economic development in an environmentally sustainable manner b. To use the country's oil and gas resources to contribute to early achievement of poverty eradication and create lasting value to society c. To develop the mineral sector for it to contribute significantly to sustainable national economic and social growth III. Major Achievements in 2018/19 ENERGY PLANNING MANAGEMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT Karuma HPP (600MW) physical progress was as at 89% as at 15th February 2019; Isimba HPP (183MW) final commissioning tests have been done and is already delivering power to the grid. The official commissioning is expected on 21st March 2019; Agago ±Achwa (42MW): The plant is undergoing final commissioning test. Electricity Transmission Projects: The following transmission projects were completed: Kawanda-Masaka T-Line 220kV, 137km line; Kawanda and Masaka substations; Nkenda-Fort Portal -Hoima 220kV, 226km line and associated Substations; Mbarara-Nkenda 132kV 160km; and the Isimba- Bujagali Interconnection project132kV, 41km line, Mbarara-Mirama 220kV, 65km line. The following transmission lines -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests .........................................................................