Let's Talk Fish- Guide for Journalists and Media to Report on These Topics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook on Environmental Law in Uganda

HANDBOOK ON ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN UGANDA Editors: Kenneth Kakuru Volume I Irene Ssekyana HANDBOOK ON ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN UGANDA Volume I If we all did little, we would do much Second Edition February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................... v Forward ........................................................................................................................................................................vi Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION TO ENVIRONMENTAL LAW ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 A Brief History of Environmental Law ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Religious, Cultural and historical roots .................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2 The Green Revolution ............................................................................................................................ 2 1.1.3 Environmental Law in the United States of America -

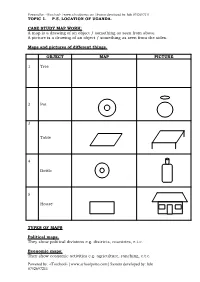

Lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION of UGANDA

Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 TOPIC 1. P.5. LOCATION OF UGANDA. CASE STUDY MAP WORK: A map is a drawing of an object / something as seen from above. A picture is a drawing of an object / something as seen from the sides. Maps and pictures of different things. OBJECT MAP PICTURE 1 Tree 2 Pot 3 Table 4 Bottle 5 House TYPES OF MAPS Political maps. They show political divisions e.g. districts, countries, e.t.c. Economic maps: They show economic activities e.g. agriculture, ranching, e.t.c. Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Physical maps; They show landforms e.g. mountains, rift valley, e.t.c. Climate maps: They give information on elements of climate e.g. rainfall, sunshine, e.t.c Population maps: They show population distribution. Importance of maps: i. They store information. ii. They help travellers to calculate distance between places. iii. They help people find way in strange places. iv. They show types of relief. v. They help to represent features Elements / qualities of a map: i. A title/ Heading. ii. A key. iii. Compass. iv. A scale. Importance elements of a map: Title/ heading: It tells us what a map is about. Key: It helps to interpret symbols used on a map or it shows the meanings of symbols used on a map. Main map symbols and their meanings S SYMBOL MEANING N 1 Canal 2 River 3 Dam 4 Waterfall Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Powered by: -iToschool- | www.schoolporto.com | System developed by: lule 0752697211 Railway line 5 6 Bridge 7 Hill 8 Mountain peak 9 Swamp 10 Permanent lake 11 Seasonal lake A seasonal river 12 13 A quarry Importance of symbols. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Journal of Conflictology Vol 4, No 2

Volume 4, Issue 2 (2013) ISSN 2013-8857 http://journal-of-conflictology.uoc.edu Table of Contents Editorial Sovereignty Conflicts. Eduard Vinyamata ............................................................................................................................... 2 Articles Legalizing Secession: The Catalan Case. Lluís Pérez and Marc Sanjaume ......................................................................... 3 The Fractured sland:I Divided Sovereignty, Identity and Politics in Ireland. Alan Bruce .................................................. 13 Sovereignty over Jerusalem. Hani Albasoos ............................................................................................................................. 23 Migingo Island: Kenyan or Ugandan Territory? Jack Shaka .................................................................................................. 32 Equatorial Guinea: An Eternal Present. Eduardo Soto-Trillo ............................................................................................... 36 Roadblocks to Peacebuilding Activities in Cyprus: International Peacebuilding Actors’ Handling of the Recognition Issue. Bülent Kanol and Direnç Kanol .................................................................................................... 39 E-journal promoted by the Campus for Peace, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya http://journal-of-conflictology.uoc.edu EDITORIAL Sovereignty Conflicts Most social unrest and international conflicts are a result of sovereignty issues. When a state -

Innovation Systems and Development the Journey of a Beleaguered Nile Perch Fishery in Uganda

Innovation Systems and Development The Journey of a Beleaguered Nile Perch Fishery in Uganda Maastricht Economic and social Research and training centre on Innovation and Technology © Copyright Rose Kiggundu, Maastricht 2006 ISBN-13: 978-90-5278-580-6 ISBN-10: 90 5278-580-5 Productie: Datawyse / Universitaire Pers Maastricht Innovation Systems and Development The Journey of a Beleaguered Nile Perch Fishery in Uganda PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Maastricht, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, Prof.mr G.P.M.F. Mols, volgens het besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 26 oktober 2006 om 12.00 uur door Rose Kiggundu UMP UNIVERSITAIRE PERS MAASTRICHT Promotor Prof. dr. Lynn K. Mytelka Co-promotor Prof. dr. Banji Oyelaran-Oyeyinka Beoordelingscommissie Prof. dr. Robin Cowan (voorzitter) Prof. dr. ir. Wiebe Bijker Prof. Joanna Chataway, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, UK Acknowledgement When I started this research and learning journey six years ago, I thought I was going to write some kind of report like I always did in my past working life with banks, non- government organizations and donor agencies. A couple of years and mentoring exer- cises later, not only did I find that the world of academia had a completely different set of principles defining its values and character but also that a dissertation had its own life. My children, family and I chose to adapt our lives to the many demands of this dissertation. The path was far from easy but we were all determined to keep going and I must say we enjoyed the rollercoaster ride. -

Economic Viability of Fishing Enterprises on Lake Victoria, Uganda

Economic viabilty of fishing enterprises on Lake Victoria, Uganda Item Type monograph Authors Wegoye, J.; Kaidhiwa, M. Publisher National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI) Download date 05/10/2021 10:31:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32861 SOCIO-ECONOMIC RESEARCH REPORT 5 LAKE VICTORIA ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROJECT ECONOMIC VIABILITY OF FISHING ENTERPRISES ON LAKE VICTORIA, UGANDA Net Annual Profits of Fishing Enterprises by Category 6,000,000 5,000,000 Net annual profits (USh/unit) profits 4,000,000annual Net 3,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 0 Paddled Paddled gill Motorised Motorised Mosquito longline nets longline gill nets seines Fishing enterprise categories Jonah Wegoye and Michael Kaidhiwa FISHERIES RESOURCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH ORGANISATION Jinja, Uganda. October, 2005 Republic of Uganda Copyright: Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF), National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) and Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project (LVEMP). This publication may be reproduced in whole or part and in any form for education or non-profit uses, without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. MAAIF, NARO and LVEMP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication which uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purpose without the prior written permission of MAAIF, NARO and LVEMP Citation: Wegoye J and M. Kaidhiwa:, 2005: Economic -

Masters Research ABSTRACTS 2013

Uganda Martyrs University SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH Masters Research ABSTRACTS 2013 Compiled by John Bosco Bampabwire Jimmy Spire Ssentongo Bruce Twesigomwe Copyright ©2018 School of Postgraduate Studies and Research All rights reserved No part of this compilation may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the School of Postgraduate Studies and Research, Uganda Martyrs University. School of Post Graduate Studies and Research Uganda Martyrs University P.O. Box 5498 Kampala - Uganda Tel: +256-382-410611 email: [email protected] ii Contents FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES ..................................................................................... 1 Master of Science in Health Services Management ...................................................................................... 1 FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES ................................................................................... 17 Master of Science Hospital Management ..................................................................................................... 17 INSTITUTE OF ETHICS AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES .......................................... 39 Masters of Arts in Development Studies ..................................................................................................... 39 FACULTY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT ............................................................... -

LVFO Strategic Plan 2016-2020

STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 - 2020 Vision “A Competitive and Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture Industry in the East African Community” Mission “To promote Sustainable Management and Development of Fisheries and Aquaculture in the East African Community for Food Security and Wealth creation” Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... vii 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Overview of the Strategic Plan 2016- 2020 ........................................................................... 2 2. Si tuation Analysis .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Legal and Policy Framework ...................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Institutional Framework ............................................................................................................. 6 2.3 Institutional Linkages................................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Functional Analysis ...................................................................................................................... -

Review of the Fisheries of Uganda Waters of Lake Albert No.3,1966.Pdf

A review of the fisheries of the Uganda waters of Lake Albert East Africa, 1928-1965/66, with catch data mainly from 1953 Item Type monograph Authors Cadwalladr, D.A.; Stoneman, J. Publisher East African Common Services Organization Download date 28/09/2021 15:22:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32856 A REVIEW OF THE FISHERIES OF THE UGANDA WATERS OF LAKE ALBERT East Africa, 1928-1965/66, witb catcb data mainly from 1953 by D. A. CADWALLADR* AND ]. STONEMAN Uganda Fisheries Department p.o. Box 4, Entebbe, Uganda, • Former address: E.A. FRESHWATER FISHERIES RESEARCH ORGANIZATION P.O. Box 343, JINJA, UGANDA , CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 t HISTORICAL 1 f Growth of Fisheries 1 Fishing Methods 3 Nets 4 e Canoes 5 CATCH DATA 6 • Methods of Collecting Data 6 Total Annual Catch and Exports to the Congo 7 Seine-net Catches 10 Long Lines 10 Gill-nets 11 Annual Catches by Species 13 PRESENT-DAY FISH PROCESSING AND MARKETING 14 DISCUSSION 17 SUMMARY 18 e ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 18 REFERENCES 18 ~. ""', 13 12~--- TOTAL ANNUAL C II 0----0 EXPORTS TO CON4 10 __.. UGANDAN CONSUMPTION LIST OF TABLES 9 1. Total annual catch, total weight of fish exported to Congo, and the \I) 8 percentage of exports to total catch 1935-1965 (1962 data not 0 7 0 available). Q 6 2. Price per ton of cured fish exports paid in the Congo, 1938-196I. I 5 II) 3. Annual production (in tons) of the Congo waters of Lake Albert, z 4 / 0 I 1950-1958. -

TERM ONE Topic: Map Work Sub Topic: Elements of a Good Map a Map (A) a Map Is a Drawing of an Object As Seen from Above

STANDARD SOCIAL STUDIES PRIMARY FIVE LESSON NOTES TERM ONE Topic: map work Sub topic: elements of a good map A map (a) A map is a drawing of an object as seen from above. Or: A map is a representation of an object as seen from above. A picture Is a drawing of an object as seen from the sides. A picture is a representation of an object seen from the sides. Difference between maps and picture - A map is a drawing of an object as seen from above while a picture is a drawing of an object as seen from the sides. - A map is not easy to understand while a picture is easy to understand. Similarities between maps and pictures - Both represent objects - Both are drawings Types of maps Political maps They show boundaries of regions, districts and countries Physical maps They show landscapes highlighting lakes, rivers and mountains Thematic maps They show comparisons between regions and countries in terms of population and tourism and minerals / energy. Elements of a good map - Map key - Map title - Map compass direction / a compass rose - Map scale - Map frame © 2018 Page 1 Map Key It is a table bearing symbols used on a map and their meaning The main function of a key is to interpret symbols and signs used on a map - Symbols are signs that represent real objects ona map Importance of map symbols - They prevent over crowding on a map - They make the map tidy - They make map reading easy. Examples Symbol meaning Quarry Bridge Rift valley Water falls River Dam Railway line Map Title It is the name or heading of a map It helps us to know what the map is all about Map Compass direction: It is a symbol that is used to show direction of places on a map Primary / cardinal points North East West South Secondary points Northwest North east South west South east Finding directions using a compass direction B A - What is the direction of point A from B? © 2018 Page 2 - Give any other examples of finding directions. -

Copyright © Anthony C.K. Kakooza, 2014 All Rights Reserved

Copyright © Anthony C.K. Kakooza, 2014 All rights reserved THE CULTURAL DIVIDE: TRADITIONAL CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS AND THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES BY ANTHONY C.K. KAKOOZA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of the Science of Law in Law in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jay Kesan, Chair Professor Bob Lawless Professor Anna-Marie Marshall Professor Thomas Ulen ABSTRACT This study addresses a number of pertinent issues concerning Traditional Cultural Expressions [TCEs], specifically in relation to what they are and the dilemma surrounding ownership vis-à-vis custodianship in an environment that is biased towards protection of Intellectual Property Rights. The present inadequate legal recognition and, ultimately, insufficient international recognition and protection of TCEs has orchestrated the misappropriation of such works for the benefit of the entertainment industry and other economic sectors as well. The biggest underlying issue therefore is – whether TCEs should be recognized within the domain of Intellectual Property Rights. The fact that TCEs are considered as part of the public domain raises a key issues as to how they can be protected so as to serve the interests of ethnic communities, States, as well as the users of the TCEs. The claim made in this study is that because of the communal nature of ownership and difficulty in defining TCEs, this has contributed to their abuse by all users. The current origin-based I.P regimes are considered as inadequate in protecting TCEs which are mainly characterized by communal ownership and absence of fixation. -

Uganda: Selected Fish Landing Sites and Fishing Communities

Uganda: Selected Fish Landing Sites and Fishing Communities Survey Undertaken by Fisheries Training Institute for the DFID Project Impacts of globalisation on fish utilisation and marketing systems in Uganda Contents Survey Information Landing Sites on Lake Victoria 1. Kasensero, Rakai District 3 2. Kasenyi, Wakiso District 7 3. Katosi, Mukono District 15 4. Kigungu, Wakiso District 20 5. Kyabasimba Rakai District 27 6. Masese, Jinja District 30 7. Ssenyi, Mukono District 34 8. Wairaka, Jinja District 38 Landing Sites on Lake Kyoga 9. Kayago, Lira District 42 10. Kikaraganya, Nakasongola District 45 11. Kikarangenye, Nakasongola District 58 12. Lwampanga, Nakasongola District 61 13. Namasale, Lira District 74 Landing Sites on Lake Albert 14. Abok, Nebbi District 78 15. Dei, Nebbi District 80 16. Kabolwa, Masindi District 84 17. Wanseko, Masindi District 88 Landing Sites on Lakes Edward and George 18. Kasaka, Bushenyi District 93 19. Katunguru, Bushenyi District 98 20. Katwe, Kasese District 99 21. Kayanja, Kasese District 105 The fieldwork was undertaken by former students at the Fisheries Training Institute in July and August 2002. They recorded their observations on the landing sites and conducted a semi-structured discussion with a group of women at each. The topics covered in the discussion are outlined on the next page. Report edited June 2004. FISHERIES GOBALISATION SURVEY PART III: FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (to be used for case study) Group: To identify women leader and those women specifically dealing in fisheries business at landing sites. 1. Can you narrate the development of fisheries over time (before export boom, when exports had just started and now) in terms of the following.