I the EFFECTS of STATE SUBVENTIONS to POLITICAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic First for the Glebe!

February 14, 2014 Vol. 42 No. 2 Serving the Glebe community since 1973 www.glebereport.ca ISSN 0702-7796 Issue no. 456 FREE Historic first for the Glebe! PHOTO: JOHN DANCE PHOTO: Back row, left to right: Old Ottawa East Hosers: Andrew Matsukubo, Charlie Hardwick-Kelly, Marcus Kelly, Cindy Courtemanche, Cameron Stewart. Glebe Goal-Getters: Liam Perras, Sophie Verroneau, Adam Perras, David Perras, Keavin Finnarty, Rachael Dillman, Councillor David Chernushenko. Kneeling, left to right: Old Ottawa East Hosers: Ian White, Natalie Saunders, Mike Souilliere. SMALL PHOTOS: CASSIE HENDRY; PHOTO OF HERON PARK HACKERS: JOHN DANCE For the next year, the Glebe Goal-Getters hockey team can honestly lay claim to and Heron Park Hackers (in red) In the end, the Glebe Goal-Getters triumphed, win- bragging rights for their win – a historic first – of the annual Capital Ward Coun- ning the championship round 8–7. cillor’s Cup. Reportedly “friendly but intense, ” the tournament was played January The tournament rules make sure this faceoff among friends remains a true shinny- 25, and participants were encouraged to be timely, appropriately dressed and sport- fest – hockey players 14 years and older play four-on-four without goalies, with at ing the right “shinny attitude.” First introduced in 2008 by former Councillor Clive least one female player per team at all times. Guaranteed at least three games of 20 Doucet, complete with trophy, the shinny tournament is now in its seventh iteration. minutes each, the four teams’ skaters must wear helmets and abide by guidelines The tradition is being carried on by Councillor David Chernushenko, who happily to keep the puck on the ice at all times. -

MARKUS BUCHART Has a BA (Hons.)

Number 77 WITH Markus Buchart, former leader, the Green Party of Manitoba MARKUS BUCHART has a B.A. (Hons.) from the University of Manitoba and an M.A. from McGill University, both in economics. He worked for six years as a Manitoba government economist, primarily in the finance department in tax policy and federal- provincial fiscal relations, and later in the environment department. He subsequently earned an LL.B. from the University of Manitoba and currently practices law, mostly civil litigation, at the Winnipeg firm of Tupper & Adams. Mr. Buchart was the leader of the Green Party of Manitoba from 1999 to 2005. He sometimes describes himself as "a recovering economist and politician.” This interview followed a speech, “Dissipated Energy,” delivered at a Frontier Centre breakfast on September 6, 2006. Frontier Centre: To what degree do you think the power. But they become efficient in other ways, too. Take, Province of Manitoba is under-pricing the domestic sale for example, Japan or Germany, or some of the western of electricity? It’s called “power at cost,” but isn’t it European economies. They have high-cost energy, but they actually “power below cost”? Manitoba Hydro says it get used to that cost environment and they end up costs about four cents a kilowatt hour to produce, but becoming more competitive generally, not just in terms of they sell it locally for about three. their power consumption. In a way, we’re attracting the dinosaurs and non-competitive industries to come here, and Markus Buchart: Yes, they admit that. At a Public Utility that’s just a losing game. -

It June 17/04 Copy

Strait of Georgia VOTE! Monday Every Second Thursday & Online ‘24/7’ at islandtides.com June 28th Canadian Publications Mail Product Volume 16 Number 11 Your Coastal Community Newspaper June 17–June 30, 2004 Sales Agreement Nº 40020421 Tide tables 2 Saturna notes 3 Letters 4 What’s on? 5 Advance poll 7 Bulletin board 11 Closely watched votes: Saanich–Gulf Islands race may be critical The electoral battle for the federal parliamentary seat in the Saanich-Gulf Islands riding has drawn national attention. It’s not just that the race has attracted four strong candidates from the Conservative, Liberal, NDP and Photo: Brian Haller Green parties. It’s that the riding has the Haying at Deacon Vale Farm, one of Mayne Island’s fourteen farms. Mayne’s Farmers Market begins in July. best chance in Canada to actually elect a Green Party member. The Green Party is running candidates in all 308 federal ridings in Elections, then and now ~ Opinion by Christa Grace-Warrick & Patrick Brown this election, the first time it has done this. Nationally, polls have put the Green t has been said that generals are always fighting the previous war. It in debate and more free votes. If this is the case, the other parties will vote at a couple of percentage points. might also be said that politicians are always fighting the last election, eventually have to do the same. The polls (as we write) indicate the possibility But the Greens have plenty of room to Iand that the media are always reporting the last election. -

List of Participants to the Third Session of the World Urban Forum

HSP HSP/WUF/3/INF/9 Distr.: General 23 June 2006 English only Third session Vancouver, 19-23 June 2006 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE WORLD URBAN FORUM 1 1. GOVERNMENT Afghanistan Mr. Abdul AHAD Dr. Quiamudin JALAL ZADAH H.E. Mohammad Yousuf PASHTUN Project Manager Program Manager Minister of Urban Development Ministry of Urban Development Angikar Bangladesh Foundation AFGHANISTAN Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Dhaka, AFGHANISTAN Eng. Said Osman SADAT Mr. Abdul Malek SEDIQI Mr. Mohammad Naiem STANAZAI Project Officer AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN Ministry of Urban Development Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Mohammad Musa ZMARAY USMAN Mayor AFGHANISTAN Albania Mrs. Doris ANDONI Director Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Telecommunication Tirana, ALBANIA Angola Sr. Antonio GAMEIRO Diekumpuna JOSE Lic. Adérito MOHAMED Adviser of Minister Minister Adviser of Minister Government of Angola ANGOLA Government of Angola Luanda, ANGOLA Luanda, ANGOLA Mr. Eliseu NUNULO Mr. Francisco PEDRO Mr. Adriano SILVA First Secretary ANGOLA ANGOLA Angolan Embassy Ottawa, ANGOLA Mr. Manuel ZANGUI National Director Angola Government Luanda, ANGOLA Antigua and Barbuda Hon. Hilson Nathaniel BAPTISTE Minister Ministry of Housing, Culture & Social Transformation St. John`s, ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 1 Argentina Gustavo AINCHIL Mr. Luis Alberto BONTEMPO Gustavo Eduardo DURAN BORELLI ARGENTINA Under-secretary of Housing and Urban Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Development Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ms. Lydia Mabel MARTINEZ DE JIMENEZ Prof. Eduardo PASSALACQUA Ms. Natalia Jimena SAA Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Session Leader at Networking Event in Profesional De La Dirección Nacional De Vancouver Políticas Habitacionales Independent Consultant on Local Ministerio De Planificación Federal, Governance Hired by Idrc Inversión Pública Y Servicios Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ciudad Debuenosaires, ARGENTINA Mrs. -

GCA Board Meeting Minutes Tuesday, September 25, 7:00 P.M

GCA Board Meeting Minutes Tuesday, September 25, 7:00 p.m. Glebe Community Centre Present: Board members: Elizabeth Ballard, Dan Chook Reid, June Creelman, Sylvia Grandi, Rochelle Handleman, Sam Harris, Jennifer Humphries, Bruce Jamieson, Angela Keller-Herzog, Sylvie Legros, Carol MacLeod, Liz McKeen, Nini Pal, Brenda Perras, Bill Price, Jennifer Raven, Bhagwant Sandu, Laura Smith, Josh VanNoppen Others: Braeden Cain, David Chernushenko, Vaughn Guy, Rose LaBrèche, Zoe Langevin, Colleen Leighton, Marianna Locke, Chari Marple, Shawn Menard, Mike Reid Regrets: Louise Aronoff, Carolyn Mackenzie, Matthew Meagher, Sue Stefko, Elspeth Tory, Sarah Viehbeck WELCOME June welcomed everyone to the meeting, and acknowledged that the GCA meets on the unceded territory of the Algonquin people. She acknowledged the municipal election candidates present (Rose LeBreche for school trustee; Shawn Menard, David Chernushenko for councillor) and welcomed Marianna Locke, a University of Ottawa PhD student studying the relationship between Landowne Park and the surrounding community. AGENDA AND MINUTES The agenda was approved as presented (moved by Nini Pal, seconded by Carol MacLeod), as were the minutes (moved by Bill Price, seconded by Elizabeth Ballard). REPORT FROM THE COUNCILLOR David Chernushenko provided updates on several items: - Anyone who needs assistance with cleaning up or recovering from the weekend’s storm can be in touch with David’s office, which has a list of volunteers who are ready to assist. - New boards have been ordered for a rink in Sylvia Holden Park. - The design to approve the drainage in Central Park West is proceeding; consultation can be found at ottawa.ca. The deadline for comments is October 10. -

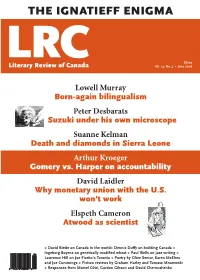

The Ignatieff Enigma

THE IGNATIEFF ENIGMA $6.00 LRCLiterary Review of Canada Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 Lowell Murray Born-again bilingualism Peter Desbarats Suzuki under his own microscope Suanne Kelman Death and diamonds in Sierra Leone Arthur Kroeger Gomery vs. Harper on accountability David Laidler Why monetary union with the U.S. won’t work Elspeth Cameron Atwood as scientist + David Biette on Canada in the world+ Dennis Duffy on building Canada + Ingeborg Boyens on genetically modified wheat + Paul Wells on jazz writing + Lawrence Hill on Joe Fiorito’s Toronto + Poetry by Olive Senior, Karen McElrea and Joe Cummings + Fiction reviews by Graham Harley and Tomasz Mrozewski + Responses from Marcel Côté, Gordon Gibson and David Chernushenko ADDRESS Literary Review of Canada 581 Markham Street, Suite 3A Toronto, Ontario m6g 2l7 e-mail: [email protected] LRCLiterary Review of Canada reviewcanada.ca T: 416 531-1483 Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 F: 416 531-1612 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie 3 Beyond Shame and Outrage 18 Astronomical Talent [email protected] An essay A review of Fabrizio’s Return, by Mark Frutkin ASSISTANT EDITOR Timothy Brennan Graham Harley Alastair Cheng 6 Death and Diamonds 19 A Dystopic Debut CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Anthony Westell A review of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and A review of Zed, by Elizabeth McClung the Destruction of Sierra Leone, by Lansana Gberie Tomasz Mrozewski ASSOCIATE EDITOR Robin Roger Suanne Kelman 20 Scientist, Activist or TV Star? POETRY EDITOR 8 Making Connections A review of David Suzuki: The Autobiography Molly -

Politicizing Bodies

This article was downloaded by: [Linda Trimble] On: 08 August 2015, At: 14:07 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Women's Studies in Communication Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uwsc20 Politicizing Bodies: Hegemonic Masculinity, Heteronormativity, and Racism in News Representations of Canadian Political Party Leadership Candidates Linda Trimblea, Daisy Raphaelb, Shannon Sampertc, Angelia Wagnerd & Bailey Gerritse a Department of Political Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada b Click for updates Doctoral Student, Department of Political Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada c Department of Political Science, University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada d Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) Postdoctoral Fellow, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada e Doctoral Student, Department of Political Studies, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada Published online: 29 Jul 2015. To cite this article: Linda Trimble, Daisy Raphael, Shannon Sampert, Angelia Wagner & Bailey Gerrits (2015): Politicizing Bodies: Hegemonic Masculinity, Heteronormativity, and Racism in News Representations of Canadian Political Party Leadership Candidates, Women's Studies in Communication, DOI: 10.1080/07491409.2015.1062836 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2015.1062836 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. -

Canadian Jurisprudence and Electoral Reform1

1 Understanding Democracy as a Cause of Electoral Reform: Canadian Jurisprudence and Electoral Reform1 Richard S. Katz Dept. of Political Science The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore MD, USA This paper addresses the question of the sources of electoral reform that lie outside of the partisan political realm. In particular, it examines the case of electoral reforms that have been imposed, or that realistically might be imagined to be imposed, by the courts in Canada. The paper consists of three major sections. The first introduces the idea of judicial review as a source of electoral reform. The second lays out the major cases relevant to electoral reform that have been decided by the Canadian courts. The third attempts to impose some theoretical consistency on the Canadian jurisprudence in this field,2 and to suggest the possible consequences of adherence to this line of development. Introduction In an often cited article, Kenneth Benoit (2004: 363) presents a theory that “predicts that electoral laws will change when a coalition of parties exists such that each party in the coalition expects to gain more seats under an alternative electoral institution, and that also has sufficient power to effect this alternative through fiat given the rules for changing electoral laws.” In a similar vein, Josep Colomer (2005: 2) presents “a logical model and discussion of the choice of electoral systems in settings with different numbers of previously existing political parties.” These articles take clear positions on two long-standing and related debates. First (and most obviously the case with Colomer, but certainly implicit in Benoit) - and following a line dating at least to John Grumm’s 1958 article on the adoption of PR in Europe - they argue that party systems are best understood as a cause rather than a consequence of electoral systems. -

Canadion Political Parties: Origin, Character, Impact (Scarborough: Prentice-Hail, 1975), 30

OUTSIDELOOKING IN: A STUDYOF CANADIANFRINGE PARTIES by Myrna J. Men Submitted in partial fulnllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1997 O Copyright by Myrna Men Nationai LiBrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services sewices bibliographiques 395 WelJiiStreet 395. nie Wellington OtEawaON KIAW -ON K1AûN4 canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Iicence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Biblioihèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, ioan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or elecîronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts Eom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. As with any thesis, there are many people to pay tribute to who helped me with this effort. It is with this in mind that 1 mention Dr. Herman Bakvis, whose assistance, advice and patience was of great value. Thanks also to Dr. Peter Aucoin and Dr. David Cameron for their commentary and suggestions. FinaLiy, 1 wish to thank my family and fnends who supported and encouraged me in my academic endeavours. -

EC 20193 Week 1

CONTESTANT'S WEEKLY LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGN RETURN X For the period beginning on the first day of the leadership contest and ending on the day that is four weeks before the end of the contest For the week ending three weeks before the end of the contest For the week ending two weeks before the end of the contest For the week ending one week before the end of the contest [Section 435.31 of the Canada Elections Act ] RAPPORT HEBDOMADAIRE DE CAMPAGNE DU CANDIDAT À LA DIRECTION Pour la période commençant le premier jour de la campagne de la course à la direction et se terminant quatre semaines avant la fin de la course Pour la semaine se terminant trois semaines avant la fin de la course Pour la semaine se terminant deux semaines avant la fin de la course Pour la semaine se terminant une semaine avant la fin de la course [Article 435.31 de la Loi électorale du Canada ] EC 20193 (12/03) CONTESTANT'S WEEKLY LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGN RETURN RAPPORT HEBDOMADAIRE DE CAMPAGNE DU CANDIDAT À LA DIRECTION PART - PARTIE - 1 Declaration [435.3(1)(c ) and (d )] Déclaration [435.3(1)c ) et d )] EC 20193-P1 (12/03) SECTION A - CAMPAIGN INFORMATION - INFORMATIONS SUR LA CAMPAGNE SECTION E - DECLARATION - DÉCLARATION Period of contest - Période de campagne Contribution reporting period - Période de rapport Beginning date Y-A M D-J Ending date Y-A M D-J Beginning date Y-A M D-J Ending date Y-A M D-J I hereby solemnly declare that to the best of my knowledge and belief: Je déclare solennellement qu'au meilleur de ma connaissance et croyance : Date de début 06 04 21Date -

Green Party of Canadamedia

Green Party of Canada Media Kit History of the Green Party around the World The first Green Party in the world, the Values Party, was started in the early 1970s in New Zealand. In the western hemisphere, the first Green Party was formed in the Maritimes in the late seventies and was called the Small Party after E.F. Schumacher's book, Small is Beautiful. In Britain, the first Green Party was called the Ecology Party, before the name "green" became common. But it wasn't until the West German Green Party -- die Groenen -- crossed the vote threshold of 5% and entered the German legislature in the late 1970s, that the green political movement started in earnest. Presently there are over 100 Green parties world-wide, and there are Green members elected in dozens of countries. Green parties have served in coalition governments in Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia and Ukraine. Legislative Achievements of Green Parties Members of Green parties around the world have been successful in their push for legislation that is consistent with the Global Green Charter, balancing ecological preservation with socially progressive values. In Paris, Deputy Mayor and Green Party member Denis Baupin, has helped push plans to ban all traffic in its congested downtown core by 2012, when Paris hopes to stage the Olympic Games. The ban will affect a nearly 5 kilometre-square area where only residents, buses, delivery vans and emergency vehicles will be allowed. In Spain, a Green party inspired bylaw has been passed which obliges builders to install solar panels to supply 60% of the hot water needs in new and fully rehabilitated residential blocks of 14 or more units, in all new heated pools, and for hospitals, clinics, schools, shopping centres and hotels. -

October, 2019

The OSCAR l October 2019 Page 1 THE OSCAR www.BankDentistry.com 613.241.1010 The Ottawa South Community Association Review l The Community Voice Year 47, No. 9 October 2019 Food, friends and fun At the Brighton Beach Clambake Friends, neighbours and alumni from Brighton Avenue gathered for the 41st Annual Brighton Beach Clambake on September 14th. See page 4 for the story. PHOTO BY PETER MCPARTLAND COMMUNITY CALENDAR Wednesday, October 2, 12:00 Doors Open for Music - The Bow Street Runners, Southminster United Thursday, October 3, 18:30 Marketing workshop, Sunnyside Library Thursday, October 3, 7:15-8:45 Christianity Explored Course Starts, Featuring live Sunnyside Wesleyan Church SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6 October 5-13 Butterfly Show, Carleton University - music by B� Mus�� Fo�d Con��t� Nesbitt Building Gentlemen of Gam�� an� MO�! Saturday, October 5, 9:00-14:00 Trinity Anglican Church Dog Wash ! Fundraiser the Woods 11:00AM-2:00P Sunday, October 6, 11:00-14:00 OSCA Fall Fest, Windsor Park Win��r Par� Wednesday, October 9, 12:00 Doors Open for Music - Foreign 1 Win��r Ave. Inspirations, Southminster United Fre� ad��so� Thursday, October 10, 19:30 - Master Piano Recital Series - Ben 21:30 Rosenblum Trio, Southminster United Wednesday, October 16, 12:00 Doors Open for Music - Inner Dialogues, www.oldottawasouth.ca Southminster United Saturday, October 19, 14:00 National Capital Opera Society Brian Law Opera Competition, Southminster United OSCA Presents Saturday, October 19, 14:00- Trinity Anglican Church’s 140th year Terrifying 16:00 Anniversary