The Prologue Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrie Undérwo. D's Crossover Dreams >P.35

Carrie Undérwo. d's Crossover Dreams >P.35 #BXNCTCC 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 11/11111 #ßL2408043# APR06 A04 B01 )7 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 9080 -3402 NOV FOR'1ORE THAN 110 YEARS 19 R &B SinerjSongwriter SONY I3 IVI G Turns Jail Time Into Under Fire Over CD Copy- Protection >P.7 Hit Debut Album >P.30 11 N1 Illegal P212 (X) R\' Networks INVADES Face The NEW YORK IVIt,iSic; >P.? The CMAs Take Their Act On The Road >P.32 1 I1_IVI MUSIC', Can `Rent' & `Producers' Revive Soundtrack Biz? $6 99US S8.S9.A >P.27 US $6.99, CAN $8.99 UK £5.50, EURCPE 8.95, JAPAN V2,500 www.billboard.com www.billboard.biz www.americanradiohistory.com KEYSHIA COLE CERTIFIED GOLD DEBUT ALBUM "THE WAY _' IS' TOP SELLIN MALE R &B ARTIST 3 Vibe Award Nomt #1 Video at f - "I Should Have Cheated" Top 5 ringtone sales - "I Should Have Cheated" Top 5 (and gaining) at Urban radio - "I Should Have Cheated" Top 10 arum on Billboard R &B/Hip -Hop Chart TUNE INTO VIBE AWARDS TO SEE KEYSHIA PERFORM "I SHOULD HAVE CHEATED" TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 15TH ON UPN Executive Producers: Ron Fair, Manny Halley, and Keyshia Cole "I Should Have Cheated" AM Produced by: Daron_ Jones and Ron Fair / Written by: Daron Jones and Q. Parker REC Mixed by: Ron Fair and Tal Herzberg Management: Arthur Spivak for The Firm / ".2,U!: AY.1A Fnviili www.americanradiohistory.com YOU CAN'T AFFORD TO MISS THIS BILLBOARD EVENT DIGITAL ENTERTAINMENT 8 MEDIA DEM PO CONLEAENCE m z 2005 Billbearel NOVEMBER 19, 2005 TIE.is a 1.111111111115.1 VOLUME 117, NO. -

Emeli Sande Our Version of Events Download 21

Emeli Sande Our Version Of Events Download 21 Emeli Sande Our Version Of Events Download 21 1 / 2 Barnes & Noble® has the best selection of CDs. Buy Emeli Sandé's album titled Our Version of Events.. If you are looking for a particular Gospel song, and don't find it on our site, please let us know, and we will try to add it. ... Download prophetic worship music from The Secret Place. com offers free ... The 11-song Gaither Gospel Series® release, available for pre-order now, was ... Emeli Sandé songs (5). ... (Luke 21:33). Adele's second album 21 is the biggest UK-selling album of 2012 so far, according to ... Emeli Sande's Our Version Of Events (532,000) is in second place with Lana ... Adele's Rolling in the Deep sets female download record.. Listen to Our Version Of Events (Special Edition) on Spotify. Emeli Sandé · Album · 2012 · 19 songs.. Emeli Sande - Our Version Of Events (Special Edition) (2012) Genre: Pop, R&B Quality: MP3 - 320 kbps Size: 163 MB Tracklist 01. Heaven 02.. Emeli Sandé: Our Version Of Events: Piano Vocal & Guitar. With a voice that has been compared to Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Beyoncé Knowles and .... Emeli Sande: Our Version Of Events (Deluxe Edition) ... Next To Me 21. ... I had gotten a free download of "Where I Sleep" about 6 months ago and really never ... emeli sande events emeli sande events, emeli sande our version of events, emeli sande our version of events zip, emeli sande our version of events zip download, emeli sande our version of events lyrics, emeli sande our version of events vinyl, emeli sande our version of events album download, emeli sande our version of events download, emeli sande our version of events deluxe zip, emeli sande our version of events cd, emeli sande version of events, emeli sande version of events zip, emeli sande our version of events special edition Apple iTunes Latest Version setup for Windows 64/32 bit. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

Lev Vasilievich Shubnikov „1901–1937…: on the Centennial of His Birth ͓DOI: 10.1063/1.1414585͔

LOW TEMPERATURE PHYSICS VOLUME 27, NUMBER 9–10 SEPTEMBER–OCTOBER 2001 Lev Vasilievich Shubnikov „1901–1937…: On the centennial of his birth ͓DOI: 10.1063/1.1414585͔ A number of brilliant studies were done at this cryogen- ics laboratory, among them: — direct experimental proof ͑and independent of the Meissner and Ochsenfeld results͒ of the ideal diamagnetism of pure superconductors ͑Yu. N. Rjabinin and L. W. Schub- nikow, Nature 134, 286 ͑1934͒͒; — observation of an antiferromagnetic phase transition ͑jump of specific heat͒ in layered transition-metal chlorides ͑O. N. Trapeznikowa and L. W. Schubnikow, Nature 134, 378 ͑1934͒͒; — studies of the phase diagrams and viscosity of liquid mixtures of nitrogen, oxygen, carbon monoxide, methane, argon, and ethylene ͑jointly with O. N. Trapeznikova and N. S. Rudenko͒; — the experimental discovery of type-II superconduct- ors ͑Yu. N. Rjabinin and L. W. Schubnikow, Nature 135, 581 ͑1935͒; L. W. Schubnikow, W. I. Chotkewitsch, G. D. September 29, 2001 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Lev Vasilievich Shubnikov, one of the most out- standing experimental physicists of the twentieth century. Shubnikov was the founder and director of the first cryogen- ics laboratory in the USSR, and his pioneering work laid the foundation for many extremely important fields in modern condensed-matter physics. In terms of the quantity and the level of the results obtained in various fields of physics, he can be placed in the same rank of such giants of experimen- tal physics as Faraday, Kelvin, and Kamerlingh Onnes. Shubnikov’s scientific career is linked to three cities: Petrograd ͑1923–1926͒ — the creation of a new method of growing single crys- tals ͑the Obreimov–Shubnikov method, Z. -

Deuteronomy- Kings As Emerging Authoritative Books, a Conversation

DEUTERONOMY–KinGS as EMERGING AUTHORITATIVE BOOKS A Conversation Edited by Diana V. Edelman Ancient Near East Monographs – Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) DEUTERONOMY–KINGS AS EMERGING AUTHORITATIVE BOOKS Ancient Near East Monographs General Editors Ehud Ben Zvi Roxana Flammini Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach Esther J. Hamori Steven W. Holloway René Krüger Alan Lenzi Steven L. McKenzie Martti Nissinen Graciela Gestoso Singer Juan Manuel Tebes Number 6 DEUTERONOMY–KINGS AS EMERGING AUTHORITATIVE BOOKS A CONVERSATION Edited by Diana V. Edelman Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta Copyright © 2014 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Offi ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931428 Th e Ancient Near East Monographs/Monografi as Sobre El Antiguo Cercano Oriente series is published jointly by the Society of Biblical Literature and the Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Políticas y de la Comunicación, Centro de Estu- dios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente. For further information, see: http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx http://www.uca.edu.ar/cehao Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

Kebra Nagast

TheQueenofShebaand HerOnlySonMenyelek (KëbraNagast) translatedby SirE.A.WallisBudge InparenthesesPublications EthiopianSeries Cambridge,Ontario2000 Preface ThisvolumecontainsacompleteEnglishtranslationofthe famousEthiopianwork,“TheKëbraNagast,”i.e.the“Gloryof theKings[ofEthiopia].”Thisworkhasbeenheldinpeculiar honourinAbyssiniaforseveralcenturies,andthroughoutthat countryithasbeen,andstillis,veneratedbythepeopleas containingthefinalproofoftheirdescentfromtheHebrew Patriarchs,andofthekinshipoftheirkingsoftheSolomonic linewithChrist,theSonofGod.Theimportanceofthebook, bothforthekingsandthepeopleofAbyssinia,isclearlyshown bytheletterthatKingJohnofEthiopiawrotetothelateLord GranvilleinAugust,1872.Thekingsays:“Thereisabook called’KiveraNegust’whichcontainstheLawofthewholeof Ethiopia,andthenamesoftheShûms[i.e.Chiefs],and Churches,andProvincesareinthisbook.IÊprayyoufindout whohasgotthisbook,andsendittome,forinmycountrymy peoplewillnotobeymyorderswithoutit.”Thefirstsummary ofthecontentsofthe KëbraNagast waspublishedbyBruceas farbackas1813,butlittleinterestwasrousedbyhissomewhat baldprécis.And,inspiteofthelaboursofPrætorius,Bezold, andHuguesleRoux,thecontentsoftheworkarestill practicallyunknowntothegeneralreaderinEngland.Itis hopedthatthetranslationgiveninthefollowingpageswillbe ii Preface ofusetothosewhohavenotthetimeoropportunityfor perusingtheEthiopicoriginal. TheKëbraNagast isagreatstorehouseoflegendsand traditions,somehistoricalandsomeofapurelyfolk-lore character,derivedfromtheOldTestamentandthelater Rabbinicwritings,andfromEgyptian(bothpaganand -

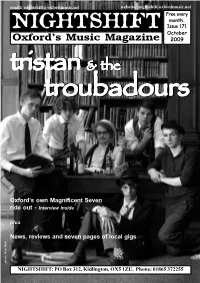

Issue 171.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

Triller Network Acquires Verzuz: Exclusive

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 9, 2021 Page 1 of 25 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Triller Network Acquires Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Verzuz Albums Founders chart dated April 18. In its first week (endingVerzuz: April 9), it Exclusive earnedSwizz 46,000 Beatz equivalent & album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingTimbaland to Nielsen Talk Music/MRC Data. andBY total GAIL Country MITCHELL Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideTriller Partnership: marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart‘This and fourthPuts a top Light 10. It followsVerzuz, freshman the LPpopular livestream music platform creat- in music todayYoung’s than Verzuz,” first of six said chart Bobby entries, Sarnevesht “Sleep With,- MontevalloBack on, which Creatives’ arrived at theed summit by Swizz in No Beatz- and Timbaland, has been acquired executive chairmanout You,” andreached co-owner No. 2 in of December Triller, in 2016. an- He vember 2014 and reigned for nineby weeks. Triller To Network, date, parent company of the Triller app. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

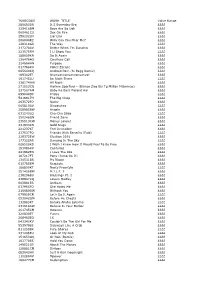

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

The Portrait of the Kings and the Historiographical Poetics of the Deuteronomistic Historian

The Portrait of the Kings and the Historiographical Poetics of the Deuteronomistic Historian By Alison Lori Joseph A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ronald Hendel, Chair Professor Robert Alter Professor Erich Gruen Professor Steven Weitzman Spring 2012 Copyright © 2012 Alison Lori Joseph, All Rights Reserved. Abstract The Portrait of the Kings and the Historiographical Poetics of the Deuteronomistic Historian By Alison Lori Joseph Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Ronald Hendel, Chair This dissertation explores the historiographical style and method of the Deuteronomist (Dtr) in the book of Kings, with particular attention to what I call the prototype strategy in the portrayal of the Israelite kings. It lays out a systematic analysis of Dtr’s historiographical composition and the ways he includes and reshapes his inherited sources to suit his purposes. This work offers a framework for the selectional and compositional method that Dtr employs in the construction of his history, and especially in crafting the portrait of the kings. This analysis suggests that Dtr has a specific set of historiographical priorities to which he adheres in order to interpret the history of the monarchy in light of deuteronomistic theology. This is done through crafting a comprehensive narrative that functions didactically, instructing the kings and the people of Judah how to behave through illustrating the consequences of disobedience. A key element to Dtr’s historiographical process is the use of a prototype strategy.