Conversation with Sri Lankan Director Dharmasena Pathiraja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewers in a More Effective Manner Are Also Compiled

Insight: A guide to films on coexistence Insight: A guide to films on coexistence Publisher FLICT – Facilitating Initiatives for Social Cohesion and Transformation ISBN 978-955-1534-18-9 Cover Design and Page Layout TSdM : civilians Edited by Hasini Haputhanthri Authors Sunil Wijesiriwardena Thilina Surath de Mel Photographs With assistance of Film directors Contents Foreword 06 Lago Rahe Munna Bhai 14 Avatar 16 Invictus 18 Dhobi Ghat 20 Lemon Tree 22 Freedom Writers 24 Lagaan 26 Machan 28 Rang De Basanti 30 Japanese Wife 32 Bombay 34 Ankur 36 Bambaru Evith 38 Mr & Mrs Iyer 40 Foreword Sri Lanka has suffered for a prolonged period of time due to the fierce conflict caused by ethnic division. Although the war is over, a complete ending to the grief is yet to happen. The social body ails not only from the ethnic conflict. Society also bleeds from violence erupting from various social fault lines such as caste, gender and many other lines of division, which may not be obvious to the naked eye. In terms of the ethnic conflict, although the protracted war has ended, it is impossible to state that the structural and cultural elements in its background have transformed and that society has developed positive peace and integration. It is time that we organized efforts that would transform Sri Lanka into a cultured, peaceful society, which incorporates integration and co- existence in its human relationships and transforms the said numerous social conflicts in a positive manner. We would like to reinforce, however, that the dominant social forces’ mere desire to contribute to such a reformist campaign is insufficient. -

The Fukuoka City Public Library Movie Hall Ciné-Là Film Program Schedule December 2015

THE FUKUOKA CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY MOVIE HALL CINÉ-LÀ FILM PROGRAM SCHEDULE DECEMBER 2015 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ARCHIVE COLLECTION VOL.9 ACTION FILM ADVENTURE WITH YASUAKI KURATA December 2-6 No English subtitles ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SRI LANKA FILMS CENTERED ON LESTER JAMES AND SUMITRA PERIES December 9-26 English subtitles ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Our library and theater will be closed for the New Year Holidays from December 28-January 4 ENGLISH HOME PAGE INFORMATION THE FUKUOKA CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY http://www.cinela.com/english/ This schedule can be downloaded from: http://www.cinela.com/english/newsandevents.htm http://www.cinela.com/english/filmarc.htm ARCHIVE COLLECTION VOL.9 Action Film Adventure with Yasuaki Kurata A collection of films starring action film star Yasuaki Kurata. December 2-6 No English subtitles TATAKAE! DRAGON VOL.1 Director: Toru Toyama, Shozo Tamura Cast: Yasuaki Kurata, Bruce Liang, Makoto Akatsuka 1974 / Digital / Color / 80 min./ No English subtitles STORY: 4 episodes from the 1974 TV series pitting a karate expert as the protagonist who goes against an underworld syndicate. (Episodes 1-4) TATAKAE! DRAGON VOL.2 Director: Toru Toyama Cast: Yasuaki Kurata, Fusayo Fukawa, Noboru Mitani / Digital / Color / 80 min./ No English subtitles STORY: 4 episodes from the 1974 TV series pitting a karate expert as the protagonist who goes against an underworld syndicate. (Episodes 14, 15, 25, 26) FINAL FIGHT SAIGO NO ICHIGEKI Director: Shuji Goto Cast: Yasuaki Kurata, Yang Si, Simon Yam 1989 / 35mm/ Color / 96min./ No English subtitles STORY: A former Asian karate champion struggles as he makes a comeback. A big hit that was shown in 33 countries. -

Silence in Sri Lankan Cinema from 1990 to 2010

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright SILENCE IN SRI LANKAN CINEMA FROM 1990 TO 2010 S.L. Priyantha Fonseka FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Sydney 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Representation of Tamils in Post War Sinhala Movies

Proceeding of International Conference on Contemporary Management - 2016 (ICCM-2016), pp 312-320 REPRESENTATION OF TAMILS IN POST WAR SINHALA MOVIES: SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MOVIES PRODUCED DURING 2010- 2012 Sivapriya.S ABSTRACT An exciting aspect of inter cultural communication is the communication processes through which one culture's perceptions of another culture are created and recreated. From a Symbolic Interactions perspective, the perceptions one culture has of another are constructed through interaction with and about the target culture. Media messages are primary sources of messages that shape one culture's perceptions of another. The existing literature insists that dominant culture often try to maintain their role as powerful and superiors among the subordinate cultures. This study uses content analysis of Sinhala movies to explore the ways in which Tamils are represented in the post war Sinhala movies and to analyze how those images contribute to the development of cultural perceptions about Tamils in Sri Lanka. The quantitative data collected through content analysis were further analyzed using qualitative approaches. The results indicate that Tamils are portrayed as cruel soldiers who are very strong about their mission and even kill their own corps for their mission, minority characters who depend on Sinhalese for their survival, depended who could be rescued by the army, emotionally weak and violent. Overall, the findings prove that Sri Lankan Sinhala war movies produced during the post war period develop a negative perception about Tamils in Sri Lanka. Keywords: Inter- cultural communication, Symbolic interactionism, Sinhala movies 1. INTRODUCTION visual medium as it can be utilized as a Cinema is one of the most important dominant tool of propaganda. -

SAARC Film Festival 2017 (PDF)

Organised by SAARC Cultural Centre. Sri Lanka 1 Index of Films THE BIRD WAS NOT A BIRD (AFGHANISTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Ahmad Zia Arash THE WATER (AFGHANISTAN/ SHORT) Directed by Sayed Jalal Rohani ANIL BAGCHIR EKDIN (BANGLADESH/ FEATURE) Directed by Morshedul Islam OGGATONAMA (BANGLADESH/ FEATURE) Directed by Tauquir Ahmed PREMI O PREMI (BANGLADESH/ FEATURE) Directed by Jakir Hossain Raju HUM CHEWAI ZAMLING (BHUTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Wangchuk Talop SERGA MATHANG (BHUTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Kesang P. Jigme ONAATAH (INDIA/ FEATURE) Directed by Pradip Kurbah PINKY BEAUTY PARLOUR (INDIA/ FEATURE) Directed by Akshay Singh VEERAM MACBETH (INDIA/ FEATURE) Directed by Jayaraj ORMAYUDE AtHIRVARAMBUKAL (INDIA/ SHORT) Directed by Sudesh Balan TAANDAV (INDIA/ SHORT) Directed by Devashish Makhija VISHKA (MALDIVES/ FEATURE) Directed by Ravee Farooq DYING CANDLE (NEPAL/ FEATURE) Directed by Naresh Kumar KC THE BLACK HEN (NEPAL/ FEATURE) Directed by Min Bahadur Bham OH MY MAN! (NEPAL/ SHORT) Directed by Gopal Chandra Lamichhane THE YEAR OF THE BIRD (NEPAL/ SHORT) Directed by Shenang Gyamjo Tamang BIN ROYE (PAKISTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Momina Duraid and Shahzad Kashmiri MAH-E-MIR (PAKISTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Anjum Shahzad FRANGIPANI (SRI LANKA/ FEATURE) Directed by Visakesa Chandrasekaram LET HER CRY (SRI LANKA/ FEATURE) Directed by Asoka Handagama NAKED AMONG PUBLIC (SRI LANKA/ SHORT) Directed by Nimna Dewapura SONG OF THE INNOCENT (SRI LANKA/ SHORT) Directed by Dananjaya Bandara 2 SAARC CULTURAL CENTRE SAARC Cultural Centre is the multifaceted realm of to foray into the realm of the SAARC Regional Centre the Arts. It aims to create an publications and research and for Culture and it is based in inspirational and conducive the Centre will endeavour to Sri Lanka. -

Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna Film Free 21

Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna Film Free 21 1 / 4 Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna Film Free 21 2 / 4 3 / 4 00:00 [sil.] 02:40 SANHINDA FILMS PRESENTS. BE POSITIVE MEDIA GROUP CREATION. A FILM .... Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna (Flying with one Wing) (Sinhala: තනි තටුවෙන් පියාඹන්න) is a 2003 Sri Lankan Sinhala drama thriller film directed by Asoka .... History. Film by Name : Search ... 21. SUJATHA. 1953. 23. WARADA KAGEDA. 1954. 25. SARADIYEL. 1954. 27 ... THANI THATUWEN PIYABANNA. 2003. 1005.. A film by Prasanna Jayakody Poetic travelogue in breathtaking countryside of Sri Lanka counterpointed with the journey of two simple men and .... Chain Reaction (film) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chain Reaction is a 1996 American ... Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna Sinhala Movie Video by Asoka Handagama Thani Thatuwen ... Par celaya oscar le mercredi, février 27 2013, 21:20 .... 06/27/18--21:22: _Musicreader Pdf 4 0. ... Download YIFY Movies torrents free in smallest size and awesome quality. ... thani thatuwen piyabanna movie 18. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia ... Films of Prasanna Vithanage, Sri Lankan Cinema and 25 Years of Civil War ... Roger Seneviratna, Anusha Sonali, Anusha Damayanthi, 18+, Adult, Released on 21 February ... Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna · Asoka Handagama, Anoma Janadari, Mahendra Perera, Gayani Gisanthika, .... to block our freedom of expression just because we see ... special jury prize at the 17th International Film. Festival ... masterpiece, Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna ... 21 Total. 22 Chatter. 26 Trendsetter. 27 Many times. 28 Tedium.. TALLINN BLACK NIGHTS FILM FESTIVAL Main Competition European Premiere Asandhimitta by director Asoka Handagama Sri Lanka, 2018.. a film Festival of the French Speaking Countries will be held from the March 16 to 20 at the Elphinstone Theatre. -

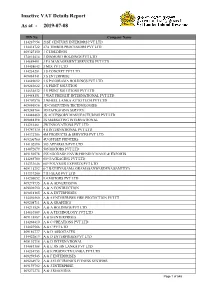

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

Journal of Visual& Performing Arts Research

1 Journal of Visual & Performing Arts Research Journal of Visual & Volume 2 Number 1 Arts & Performing Visual Research Journal of Performing Arts Research Volume 2 Number 1 Articles 5-12 Historicizing the Presentation of Sri Lankan 75-88 Vivienne Westwood and her Fashion Mantra Dancers in Colonial Exhibitions W. ADIKARAM and A.T.P. WICKRAMASINGHE SUDESH MANTILLAKE 89-101 Re-Shaping National Culture: 13-23 Gamelan Serdang and Gamelan Shanghai: Sean-nós Dance in Twenty-First Century Creative Dealing with Non-Appropriation Ireland and Academic Categorizations in Asia BRIDGET RYAN GISA JÄHNICHEN 103-127 inr.uq l,jdk k¾;k rx. ffY,sfha Ndú; velals 25-35 Silence as ‘Weapon’: Listening to ‘Silent’ jdok l,dj ms<sn| úu¾Ykd;aul wOHhkhla Characters in Sri Lankan Cinema y¾IK uOqIxl ú;drK PRIYANTHA FONSEKA Volume 2 Number 1 Volume 37-49 Sri Lankan String Instruments and their 129-139 Beyond Shakespeare’s Globe: National Presentation: The Case of the Women Playwrights of Golden Age Spain “Ravanhatta” HARLEY ERDMAN CHINTHAKA PRAGEETH MEDDEGODA 51-73 hg;Aúð; YS% ,dxflah jd¾;d PdhdrEmj, ksrEms; iajfoaYsl foayh ms<sn`o wOHhkhla ^ls%'j' 1843-1948& tia' tï' ÿ,dÍ .h;s%ld iQßhnKavdr Rs. 800 ISSN 2651-0286 FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES University of the Visual & Performing Arts, Sri lanka ISSN 2651-0286 https://vpa.ac.lk/faculty-of-graduate-studies 2 CHIEF EDITOR Journal of Visual & Prof. Saumya Liyanage Performing Arts Research EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Faculty of Graduate Studies Samal Vimukthi Hemachandra Natasha Hillary Volume 2 Number 1 - 2019 Dr Achala Abeykoon EDITORIAL BOARD Dr Indika Ferdinando Dr Chinthaka Prageeth Meddegoda JOURNAL AIM AND SCOPE Dr Priyantha Udagedara FGS Journal of Visual and Performing Arts Research is an annual ADVISORY BOARD research journal published by the Faculty of Graduate Studies, Senior Prof. -

LUNGOMETRAGGI in CONCORSO FILIPPINE TAMBOLISTA Fino All’Ultimo Battito / Drum Beat Adolfo Alix Jr

LUNGOMETRAGGI IN CONCORSO FILIPPINE TAMBOLISTA Fino all’ultimo battito / Drum beat Adolfo Alix jr. Sceneggiatura / Screenplay Regina Tayag Fotografia / Photography Albert Banzon Montaggio / Editing Aleks Castaneda Suono / Sound Ditoy Aguila Interpreti / Cast Sid Lucero, Coco Martin, Jiro Manio,Ricky Davao, Anita Linda Produzione / Production Creative Programs Inc. & Bicycle Pictures (Arlen Cuevas), Cinema One Originals Anno di produzione / Year of production 2007 Durata / Running time 90 Formato / Format DV Adolfo Alix jr. Hai mai desiderato così tanto una cosa da fare qualsiasi cosa per ottenerla? Tambolista parla del desiderio di un ragazzo di Si è laureato a Manila in comunicazio- possedere una batteria. Ambientato nei quartieri degradati di ni. All’età di 18 anni ha vinto il primo premio della competizione nazionale Manila, il film è girato dal punto di vista di un adolescente di della Fondazione per lo Sviluppo 14 anni, Jason, che sta per diventare uomo. Quando suo fra- Cinematogarfico come sceneggiatore. tello maggiore Billy mette in cinta la ragazza, i due fratelli, Ha co-sceneggiato Mgna Munting insieme al compagno di strada Pablo, cercano di procurarsi i Tinig di Gil Portes, che ha vinto diver- soldi per pagarle l’aborto. Questi tre caratteri ci mostrano si premi, Beautiful Life di Gil Portes, Homecoming and Mourning Girls e come la lotta per sopravvivere a una vita da disperati, diventa D’Anothers di Joyce Bernal ed è stato anche una lotta per conservare la propria umanità. Un ritratto scenografo in Mano Po di Joel Laman- intimo di due fratelli che vivono privi di mezzi, dove ogni bat- ga. Il suo primo lungometraggio come tito ha la sua importanza. -

Annual Report of the University of the Visual

VISION To be the centre of excellence for serenity of the mankind through Visual and Performing Arts. MISSION To offer culturally enriching opportunities to all students and members of the University. To obtain prominence in the Asian region while conforming to the technological advancement in relation to Arts and Crafts in an environment which stimulates creativity. CONTENT 1. Executive Summary of the Vice Chancellor-2017 158-164 1.1 Organizational Structure 165 1.2 University Council 166 2. Details of Students and Resources 167-170 3. Postgraduate Degree Program - Sinhala (Medium) 170 4. External Degree Programmes 170 5. Details of the payment of Research Allowance 171 5.1 Details of the Research papers presented at the research symposium held from 171-174 15.11.2017 to 17.11.2017 6. Details of Staff 175 6.1 Approved Cardre 175 6.2 Details of Distribution of Academic and Academic Support Staff in Corresponding 175 units/Faculties 6.3 Details of Administrative and Non Academic Staff Staff in Corresponding 176 units/Faculties 6.4 Total Staff Movement 177 7. Staff Development 178 7.1 Details of Workshops, Seminars participated by Administrative Staff members 178-179 7.2 Details of Workshops, Seminars participated by Non Academic Staff members 180 8 .Details of Infrastructure Facilities 181 9. Comparative Details of the Library Books Collection 2016/2017 181 10. Details of Mahapola Scholarship and Bursary Recipients - 2016/2017 181 11. Audit Committee Report- 2017 182 12. Statement of Financial Performance -2017 183-214 13. Auditor General's Report on Accounts for the 215-223 Year Ending 31st December 2017 14. -

D E Sig Ng Ra Ph Iq Ue

4€ Design graphique : Marion Tigréat / www.mariontigreatportfolio.com Lyannaj ! Une expression découverte ici à la faveur du mouvement populaire qui a agité La Guadeloupe, La Martinique… Et la « métropole » au début du printemps. Si le vocable Pwofitation a lui aussi connu un grand succès public, c’est au Lyannaj que nous dédions notre 9ème édition. Formidable langue créole qui nous offre ce mot en partage… Littéralement « lianer », c’est nouer, relier, vivre ensemble, et faire ensemble. Or depuis 2001, notre propos est justement de créer ce « Lyannaj » à Groix. Les insulaires et les amoureux des îles s’y retrouvent autour du cinéma, de la musique, et des débats. Lyannaj… à Sri Lanka. Notre île invitée en a bien besoin ! L'actuelle défaite militaire de la rebellion séparatiste tamoul met fin à près de 30 ans d'un conflit qui aura fait plus de 80 000 morts. Sans partis pris, autre que celui des populations civiles, nous avons invité des personnalités qui défendent la paix, la démocratie, et le « vivre ensemble », toutes confessions et ethnies confondues. En partenariat avec Amnesty International, nous vous proposons une vingtaine de films en provenance de l’île « aux mille sourires » et aux mille peines, en majorité inédits en France. Lyannaj toujours, mais cette fois contre la pwofitation. Nous vous invitons, par des films et des débats, à revenir sur le formidable séisme qui a secoué La Guadeloupe et la Martinique, avant de nous arrêter une nouvelle fois chez leur voisine Haïti. Nous la fêterons à travers des documentaires et des concerts afin d’amorcer notre futur partenariat avec la commune des Abricots et son maire Jean-Claude Fignolé. -

34Thsarasaviya Awards

34TH SARASAVIYA AWARDS SALUTES TO THE LEGACY OF DR JAMES PERIES SACHITRA MAHENDRA hen the 45-year old journalist who had already made his career as a filmmaker entered WAsoka Hall in 1964, he sensed the limelight. He was a mere Lester James Peries with no credentials to Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe hands over a special Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe reminiscing the his name. Yet he could reach for many trophies with award to Dr Lester James Peries’ wife, Sumitra Peries. first Sarasaviya Awards Festival. much ease. The limelight was soon to be in his favour. The strange turn of fate brought another audience member who was only 20 years back then. 54 years Distinguished audience later, he graced the occasion as the country’s Prime Minister to recall how things unfolded back then a few metres away from the conventional VIP lecture pedestal. The 34th Cargills Sarasaviya Film Festival, held at the BMICH on August 3, was themed to pay tribute to Dr Lester James Peries. Dr Peries is known not only for his meteoric rise to the ecclesiastical echelons of local cinema but also for the illumed presence right through- out the Sarasaviya Film Festival chronology. BEST DIRECTOR AND SCRIPTWRITER OF 2016, SPECIAL JURY AWARD RECIPIENT, The country’s oldest film festival returned to the SHAMEERA RANGANA NAOTUNNA (MOTOR BICYCLE) Sarasvathi performance PRASANNA VITHANAGE (USAVIYA NIHANDAI DOCUMENTARY). stellar gallery following a brief spell of absence. The return was not easy as quite a few festivals have already joined the ring to steal the show. The Sarasaviya fest was nevertheless armed with superior weaponry.