Pickles and Pastrami: the Core of the American Jew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leo's Delicatessen Offers Daily Specials. Inquire by Visit Or Phone

Leo’s Delicatessen Leo’s Delicatessen is open the following offers daily hours to serve you. specials. Inquire Weekdays by visit or phone Monday - Thursday 11:00am - 7:00pm for today’s Friday 11:00am - 4:00pm selection. Traditional NY Weekends Saturday - Closed Delicatessen food Sunday - 11:00am-6:00pm served right here in Rochester, NY! Leo’s accepts cash and credit cards as forms of payment. 585/784-6825 Established 2008 Leo’s Deli is a service of the Jewish Home of Rochester 2021 Winton Road S. Rochester, NY 14618 585/784-6825 Soups Signature Sandwiches Traditional Favorites Leo’s Delicatessen uses only the freshest Delicatessen specialties offered every day at Leo’s. Choose from the following traditional ingredients when preparing their soups. Sandwiches are served with kosher dill pickle, and choice delicatessen favorites. Each day we offer a specialty ‘Soup of of cole slaw, macaroni or potato salad. the Day’. Be sure to ask us for today’s Knish $3.50 A classic deli favorite. special! Hot Corned Beef $10.95 A Jewish Home favorite! Corned Beef, tender and piled Latkes $3.50 Soup of the Day $2.75 cup high, served on Rye bread. Served with apple sauce and tofutti $3.50 bowl A delicious homemade soup sour cream. $8.75 quart $10.95 prepared fresh daily. Hot Pastrami Supremely delicious beef pastrami. Stuffed Cabbage $5.95 Matzo Ball Soup $2.75 cup Ground beef and rice cooked in $3.50 bowl Just like mom makes! cabbage leaves and served with a tangy $8.75 quart Traditional Deli Sandwiches tomato sauce. -

Russian Restaurant & Vodka Lounge M O SC O W

Moscow on the hill Russian Restaurant & Vodka Lounge Appetizers Russian meals always start with zakuski. Even in the most modest households there is some simple dish, if only a her- ring, to go with a glass of vodka. Zakuski become more elaborate and lavish according of to the wealth of each family. Appetizer Tasting Platter (served with bread basket) 19.95 Chef’s selection of appetizers. Today’s selection is presented on our Specials menu Russian Herring 7.95 Chilled Beet Soup Svekolnick 4.95 Cured herring filet, onion, olives, pickled beets,baby potatoes, Beets broth, lemon juice, chopped cucumber, hardboiled egg, dill, cold-pressed sunflower oil green onion, dill, sour cream Blini with Chicken 7.95 Borscht 4.95 Two crepes stuffed with braised Wild Acres chicken, served Classic Russian beet, cabbage and potato soup garnished with with sour cream sour cream and fresh dill Blini with Caviar 9.95 Piroshki (Beef and Cabbage) 7.95 Salmon roe rolled in crepe with dill, scallions, sour cream Two filled pastries, dill-sour cream sauce Duck “Faux” Gras Pate 5.95 Assorted Pickled Vegetables 4.95 Wild Acres farm duck liver pate, fruit chutney, toasts Seasonal variety of house pickled vegetables Lamb Cheboureki 7.95 Russian Garden Salad 6.95 Ground lamb-stuffed pastries puffed in hot oil, Tomato, cucumber, bell pepper, sweet onion, lettuce tossed with served with tomato-garlic relish cold-pressed sunflower oil vinaigrette, green onion & fresh dill Escargot 9.95 Side Salad 5.95 White wine garlic butter sauce and sprinkled with cheese Mixed greens, -

Amelia Answers 5 Questions About the Seasonal

Five Questions for Amelia Saltsman To paraphrase the age-old question, how is this Jewish cookbook different from all others? We tend to compartmentalize the different aspects of our lives. We have one box for the seasonal, lighter, healthier way we eat today, and another for Jewish food, which is often misunderstood as heavy, only Eastern European (Ashkenazic), or irrelevant to today’s lifestyle. (This box also often holds wistful memories for beloved foods we think we’re no longer supposed to eat.) In The Seasonal Jewish Kitchen, I want to open up all those boxes and show how intertwined tradition and modern life actually are. I’ve read the Bible for history and for literature, but now I’ve mined it for food, agriculture, and sustainable practices, and wow, what a trove of delicious connections I discovered! What kind of surprises will readers discover? First, the great diversity of Jewish cuisine. The Jewish Diaspora, or migration, is thousands of years old and global. Jewish food is a patchwork of regional cuisines that includes the deli foods of Eastern Europe and the bold flavors of North Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and more. My hope is that The Seasonal Jewish Kitchen will keep you saying, “That’s Jewish food? Who knew?” Remember the line from Ecclesiastes about there being nothing new under the sun? The ancient Hebrews were among the world’s early sustainable farmers, and many of today’s innovative practices have their roots in the Bible. Also, the Bible contains quite a few “recipes” that are remarkably current (think freekeh, fire-roasted lamb, and red lentil stew). -

Ingredients HANUKKAH 2020

Ingredients HANUKKAH 2020 Herb Roasted Carrots Chocolate Hazelnut Babka Main Dishes GLUTEN-FREE, VEGAN Enriched unbleached flour (wheat flour, Carrots, canola/olive oil blend, minced malted barley flour, niacin, iron, thiamin Red Wine Braised Brisket garlic in water (dehydrated garlic, water, mononitrate, riboflavin, folic acid), Brisket, salt, pepper, canola/olive oil blend, citric acid), parsley, mint, salt, pepper. Chocolate hazelnut spread (sugar, palm oil, shallots, celery, garlic, thyme, Manischewitz hazelnuts, skim milk, cocoa, soy lecithin, Concord Grape Wine, chicken stock, bay Roasted Asparagus vanillin), Water, chocolate chips (sugar, leaves. GLUTEN-FREE, VEGAN chocolate, milkfat, cocoa butter, soy lecithin, Asparagus, lemon zest, canola/olive oil natural flavor), Brown sugar (sugar, Chicken Marbella blend, salt, pepper. molasses), milk, eggs, unsalted butter Olive oil, red wine vinegar, prunes, green (sweet cream, natural flavoring). Contains olives, capers, bay leaves, garlic, oregano, Roasted Fingerling Potatoes 2% or less of each of the following: salt, black pepper, chicken, white wine, salt, yeast. brown sugar, parsley. with Rosemary GLUTEN-FREE, VEGAN Allergens: Wheat, Milk, Eggs, Tree Nuts Roasted Salmon on Cedar Plank Fingerling potatoes, canola/olive oil blend, salt, pepper, rosemary. Cinnamon Babka Lemon Pepper, BBQ, Tom Douglas Salmon, Enriched unbleached flour (wheat flour, spices, salt, pepper. Wild Rice Pilaf malted barley flour, niacin, iron, thiamin GLUTEN-FREE, VEGAN mononitrate, riboflavin, folic acid), Water, Wild Rice, Brown Rice, Pink Lady Apples, brown sugar (sugar, molasses), milk, eggs, Pecans, Celery, Green Onion, Cranberries, unsalted butter (sweet cream, natural Prepared Foods Zupan’s Orange Juice, Honey, Orange Zest, flavoring), cane sugar. Contains 2% or less Latkes (Potato Pancakes) Canola Oil, Olive Oil, Lemon Juice, Salt, of each of the following: salt, yeast, VEGETARIAN Pepper. -

Downtown BREAKFAST SANDWICHES SPECIAL SMOKED TROUT SALAD

3150 24TH STREET, SAN FRANCISCO / (415) 590-7955 / WISESONSDELI.COM SIGNATURE SANDWICHES TOASTED BAGELS ise Sons is all sandwiches served with pickles W EVERYTHING SESAME POPPY PLAIN committed to crafting add potato salad or coleslaw +3 fries +4 authentic Jewish deli ONION SALT & PEPPER BIALY using the very best CINNAMON RAISIN CHOICE OF MEAT: ingredients available. each 2 / half dozen 11 / dozen 20 PASTRAMI CORNED BEEF SMOKED TURKEY add coriander & pepper brined with garlic & brined & lightly We SMOKE OUR tomato, radish, red onion, lettuce, hippie greens crust, smoked over a special blend smoked turkey OWN pastrami over real salted cucumber or capers +50¢ each add smashed avocado +2 real hickory of spices breast hickory wood, we bake our breads and bagels BAGEL & SHMEAR....................................... THE PURIST................................................12 FRESH. .5 choice of meat served on our double-baked rye SHMEARS – plain 3 veggie 4 scallion 4 We use cage-free eggs, smoked salmon* 4.5 .5 THE REUBENS...........................................13 free-range poultry, vegan sunflower 'cream cheese' 4.5 OG – russian dressing, swiss & sauerkraut LOCAL produce and SPREADS – butter 3 smashed avocado 4 preserves 4 KIMCHI – russian dressing, melted cheese & kimchi beef from cattle that have NEVER, EVER CLASSIC SMOKED SALMON*....closed 11 open 13.75 VEGETARIAN – sub 12 roasted mushrooms been treated with smoked salmon with capers, red onion & plain shmear hormones or antibiotics. THE NO. 19................................................13.5 VEGGIE DE-LUXE........................................8 our tribute to Langer's Deli in LA! untoasted with coleslaw, veggie shmear, salted cucumber, red onion, hippie greens & capers russian dressing & cold swiss on rye Downtown BREAKFAST SANDWICHES SPECIAL SMOKED TROUT SALAD.......................... -

Homemade Pastrami with Coriander-Pepper Rub

HOMEMADE PASTRAMI WITH CORIANDER-PEPPER RUB SERVES: 6 TO 8 | PREP TIME: 10 MINUTES | SOAKING TIME: 8 TO 16 HOURS | COOKING TIME: 4½ TO 5½ HOURS STANDING TIME: 1 HOUR | CHILLING TIME: AT LEAST 8 HOURS | SPECIAL EQUIPMENT: SPICE MILL; WATER SMOKER; 2 LARGE HANDFULS APPLE WOOD CHUNKS; HEAVY-DUTY ALUMINUM FOIL; SPRAY BOTTLE FILLED WITH WATER; INSTANT-READ THERMOMETER RUB A butcher in a New York deli might take weeks to make cured, spice-crusted, and smoked pastrami from raw 1½ tablespoons black peppercorns brisket, but my streamlined version starts with a store-bought corned beef, greatly reducing the prep time. 1½ tablespoons coriander seed 1½ teaspoons yellow mustard seed 1½ teaspoons paprika 1 In a spice mill coarsely grind the peppercorns, aluminum foil. Spray the brisket on both ¾ teaspoon granulated garlic coriander seed, and mustard seed (see tip sides with water, and then tightly wrap in the ¾ teaspoon granulated onion No. 2 below). Put the ground spices in a bowl foil. Return the brisket to the smoker and ¾ teaspoon crushed red pepper flakes and add the remaining rub ingredients. continue cooking over indirect low heat, with the lid closed, until an instant-read thermometer 1 corned beef brisket, about 2 Drain the brisket and rinse well under cold inserted into the thickest part of the meat 4 pounds, preferably the flat end running water. If necessary, trim the fat cap so registers 190°F to 195°F, 2½ to 3½ hours more. Vegetable oil it is about ⅓ inch thick, but no less. Place the Remove from the grill, open the foil, lift the brisket in a deep roasting pan or other food-safe brisket from the juices, and place it on a clean container and cover it completely with cold piece of foil. -

Nutritionals Updated

Nutritionals Updated - TooJay's Menu Please be aware that during normal kitchen operations involving shared cooking and preparation areas, the possibility exists for cross contact with allergens and gluten- free products. Please be aware that we use common fryer oil so cross-contact with any fried items may occur and could include egg, fish, milk, nut, soy and wheat allergens. Every opportunity is taken to minimize the exposure where possible. Due to these Calories Sugars (g) Protein (g) Total fat (g) Trans fat (g) circumstances, we are unable to guarantee that any menu item can be completely free Sodium (mg) Dietary fiber (g) Dietary Potassium (mg) Saturated fat (g) Calories from fat Calories (mg) Cholesterol Poly unsat fat (g) Carbohydrates (g) Carbohydrates of allergens. fat (g) Mono unsat Limited Time Offer (LTO) Seasonal Items Turkey Cranberry Griller (with slaw, fries and pickle) 1000 390 44 17 0 5 4.0 125 3250 470 109 6 34 Pastrami Grilled Cheese Roasted Veggie Pasta 1410 770 87 18 23 37 30 1310 770 131 10 8 Roasted Veggie Pasta with Chicken 1730 840 95 20 24 40 200 1590 1280 131 10 8 Roasted Veggie Pasta with Shrimp 1530 780 89 18 23 38 270 1580 990 131 10 8 Red Velvet Cake (Slice) 680 290 33 15 0 5 4.5 85 860 160 88 1 64 33 Red Velvet Cake (Whole) 5640 2410 272 120 2.0 44 39 680 7160 1330 731 8 526 265 Starters Beer Battered Onion Rings w/ Remoulade sauce 1490 1050 119 19 25 2180 30 95 19 10 Cheese Blintzes (2) - plain 880 560 63 25 0 15 8 290 760 250 62 39 19 Cheese Blintzes (2) w/ blueberry topping 1030 560 63 25 0 15 8 290 -

Chanukah Cooking with Chef Michael Solomonov of the World

Non-Profit Org. U.S. POSTAGE PAID Pittsfield, MA Berkshire Permit No. 19 JEWISHA publication of the Jewish Federation of the Berkshires, serving V the Berkshires and surrounding ICE NY, CT and VT Vol. 28, No. 9 Kislev/Tevet 5781 November 23 to December 31, 2020 jewishberkshires.org Chanukah Cooking with Chef The Gifts of Chanukah Michael Solomonov of the May being more in each other’s presence be among World-Famous Restaurant Zahav our holiday presents On Wednesday, December 2 at 8 p.m., join Michael Solomonov, execu- tive chef and co-owner of Zahav – 2019 James Beard Foundation award winner for Outstanding Restaurant – to learn to make Apple Shrub, Abe Fisher’s Potato Latkes, Roman Artichokes with Arugula and Olive Oil, Poached Salmon, and Sfenj with Cinnamon and Sugar. Register for this live virtual event at www.tinyurl.com/FedCooks. The event link, password, recipes, and ingredient list will be sent before the event. Chef Michael Solomonov was born in G’nai Yehuda, Israel, and raised in Pittsburgh. At the age of 18, he returned to Israel with no Hebrew language skills, taking the only job he could get – working in a bakery – and his culinary career was born. Chef Solomonov is a beloved cham- pion of Israel’s extraordinarily diverse and vibrant culinary landscape. Chef Michael Solomonov Along with Zahav in Philadelphia, Solomonov’s village of restaurants include Federal Donuts, Dizengoff, Abe Inside Fisher, and Goldie. In July of 2019, Solomonov brought BJV Voluntary Subscriptions at an another significant slice of Israeli food All-Time High! .............................................2 culture to Philadelphia with K’Far, an Distanced Holidays? Been There, Israeli bakery and café. -

BREAKFAST Sabich Platter Hummus, Tahina, Jerusalem Salad, Eggplant, Latke, Egg, Mint, Parsley, Amba & Harissa with Pita

BREAKFAST Sabich Platter Hummus, tahina, Jerusalem salad, eggplant, latke, egg, mint, parsley, amba & harissa with pita..............10.95 Served until 2:00 Weekdays, 3:00 Weekends Kasha Varnishkes (v optional) Hash Browns Mon-Thurs / Home Fries Fri-Sun Buckwheat groats and pasta with a baked egg and sautéed vegetables. Served with sour Two strictly fresh eggs Any style ...........................8.95 cream ..............................................................................................9.95 With grilled pastrami, salami or sausage .....................12.25 Brisket au jus, no vegetables ....................................................12.95 Eggs & Onions Scrambled Eggs and Onions ..........9.95 Egg Za’atar Pita With labne, tahina, zhoug, Jerusalem salsa, mint and parsley ................................................................7.75 LEO The classic. Lox, Eggs, and Onions .....................15.25 Shakshouka (v) One egg baked in rich, spicy tomato sauce TEO Same as above, sub 3 oz smoked trout...............14.95 with cumin, oregano and parsley. Served with pita, labne, Kippers & Eggs Half kipper, two eggs any style and zhoug ..............................................................................................9.95 grilled onions .....................................................................14.95 Saul’s Deli Hash Delectable morsels of corned beef, Plain Omelette ...............................................................8.95 pastrami, salami and hash browns with two poached eggs and Add sauteéd -

Delicatessen Catering

PARTY SLOPPY JOES 12 Serves 6 to 7 peop ...............................le ... 22 – 24 pieces per tray 14 Serves 9 to 10 peop ...............................le . 36. – 38 pieces per tray 12" Party Joes 12" Salad Party Joe Ham .................................................... 40.00 Tuna .................................................... 45.00 Turkey ................................................. 41.00 Egg Salad ............................................. 39.00 TRIO .................................................... 42.00 Chicken Salad ..................................... 42.00 Corned Beef ........................................ 43.00 Pastrami .............................................. 43.00 Individual Sandwiches Roast Beef ........................................... 43.00 per sandwich Grilled Chicken and 14" Party Joes Roasted Peppers ............................ $9.95 Eggplant, Fresh Mozzarella, Ham .................................................... 50.00 Roasted Peppers .............................. 9.95 Turkey ................................................. 51.00 Grilled Vegetables ................................. 9.95 Roast Beef ........................................... 53.00 Sloppy Joes ......................................... 10.00 Open 7 Salad s TRIO ................................................... 52.00 Days Cold Cut s Corned Beef ........................................ 53.00 in quarters on rye, wraps or roll A Sloppy Jo e .................. 9.50 Week Sandwiche s Tea Sandwiches Consists of Tuna, Egg -

A Taste of Teaneck

.."' Ill • Ill INTRODUCTION In honor of our centennial year by Dorothy Belle Pollack A cookbook is presented here We offer you this recipe book Pl Whether or not you know how to cook Well, here we are, with recipes! Some are simple some are not Have fun; enjoy! We aim to please. Some are cold and some are hot If you love to eat or want to diet We've gathered for you many a dish, The least you can do, my dears, is try it. - From meats and veggies to salads and fish. Lillian D. Krugman - And you will find a true variety; - So cook and eat unto satiety! - - - Printed in U.S.A. by flarecorp. 2884 nostrand avenue • brooklyn, new york 11229 (718) 258-8860 Fax (718) 252-5568 • • SUBSTITUTIONS AND EQUIVALENTS When A Recipe Calls For You Will Need 2 Tbsps. fat 1 oz. 1 cup fat 112 lb. - 2 cups fat 1 lb. 2 cups or 4 sticks butter 1 lb. 2 cups cottage cheese 1 lb. 2 cups whipped cream 1 cup heavy sweet cream 3 cups whipped cream 1 cup evaporated milk - 4 cups shredded American Cheese 1 lb. Table 1 cup crumbled Blue cheese V4 lb. 1 cup egg whites 8-10 whites of 1 cup egg yolks 12-14 yolks - 2 cups sugar 1 lb. Contents 21/2 cups packed brown sugar 1 lb. 3112" cups powdered sugar 1 lb. 4 cups sifted-all purpose flour 1 lb. 4112 cups sifted cake flour 1 lb. - Appetizers ..... .... 1 3% cups unsifted whole wheat flour 1 lb. -

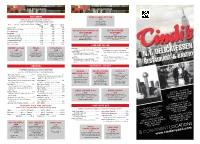

5 Convenient Locations

EGG VARIETY CINDI’S COMBO PLATTER Served with a Choice of Grits, Hash Browns or Home Fries and 13.95 a Choice of Toast, Buttermilk Pancakes, Biscuits and Gravy, or Bagel. One Stuffed Cabbage, Cottage Cheese or sliced Tomatoes may be substituted for Hash Browns. One Potato Pancake, Cheese . .add .95 Egg substitutes available: Egg Whites . .add .95 Egg Beaters . .add .95 and One Meat Knish 3 EGGS 2 EGGS 1 EGG Eggs (Any Style) . 7.75 . 7.25. 6.75 Link or Patty Sausages & Eggs . 9.00 . 8.50. 8.00 Bacon Strips & Eggs . 9.00 . 8.50. 8.00 OPEN FACED CORNED BEEF HOT ROAST BEEF Ham & Eggs . 9.25 . 8.75. 8.25 OR PASTRAMI OR TURKEY Canadian Bacon & Eggs . 10.25 . 9.70. 9.20 13.95 12.95 Ground Beef Patty & Eggs . 10.25 . 9.70. 9.20 Served over Grilled Potato Knish, Potato Salad Served Open Faced on White Bread with Gravy. or Cole Slaw w/Gravy Chicken Fried Steak & Eggs . 10.00 . 9.50. 9.00 Served with French Fries or Potato Salad With Meat Knish 14.95 and Cole Slaw Corned Beef Hash & Eggs. 10.25 . 9.70. 9.20 Pork Chops & Eggs . 11.50 . 11.00. 10.50 Ribeye Steak & Eggs. 16.00 . 15.50. 15.00 SOME LIKE IT COLD CHORIZO & EGGS MIGAS LOX & EGGS Fruit Platter . 9.95 Egg Salad . 8.95 9.50 9.50 12.95 Assorted Seasonal Fruit "You'll love this one" Served with Lettuce, Tomatoes, Cole Slaw and Mexican Sausage mixed 2 Eggs, Jalapenos, Onions, 3 Scrambled Eggs, Lox, Onions Chicken Salad .