“Headlong” Into Pieter Bruegel's Series of the Seasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOBKOWICZ PALACE Lobkovický Palác

which is currently used as the offices of the Goethe Institute. Until 1939 the Embassy of the German Reich was located in the The Lobkowicz Palace Thunovská Street 18. The Lobkowicz Palace is one of the grandest and most impressive Baroque palaces in Prague. It was built by the Master of the Court Mint Count Karel Přehořovský of Kvasejovice, who probably 1989 commissioned the architect Giovanni Battista Alliprandi (1655– The Lobkowicz Palace played an important role in recent German 1720). The palace was built between 1703 and 1707 on the site history, thanks to the events of summer and autumn 1989. East of the house “At the Three Musketeers” and the former brewery German citizens, hoping to emigrate to the West, sought sanctuary of the Strahov Monastery. Count Přehořovský overstretched his at the Embassy. Initially they were able to camp down in the attic, resources and was forced to sell the palace in 1713. After changing but as their numbers grew rapidly, they were allowed to stay in hands several times, in 1753 the palace ended up in the hands of the offices and reception rooms of the palace. In the end tents had the Lobkowicz family as a dowry. For the next 175 years it was to be put up in the garden. By the end of September there were the main Prague seat of the Hořín-Mělník branch of the family, about 4,000 East German citizens on the Embassy premises. On 30 founded in 1753. After a fire, the family employed the architect September 1989, the West German Foreign Minister, Hans-Dietrich Ignaz Palliardi (1737–1824) to add the top floor. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Prezentace Aplikace Powerpoint

PROPOSAL FOR Ms. Helena Novakova US trip, 40 pax May, 2018 PRAGUE/Czech Republic About destination PRAGUE – THE GOLDEN CITY About destination PRAGUE – THE GOLDEN CITY About destination PRAGUE – THE GOLDEN CITY ‘Prague – the golden city.’ There can hardly be another town in the whole of central Europe that has been so often and so variously praised by the figures from all spheres of the arts. Rainer Maria Rilke described his birthplace, as “a vast and rich of epic of architecture”, and Goethe labeled it “the most beautiful jewel in the Bohemian crown”. The 19th-century Czech writer and journalist Jan Neruda, whose characteristically humorous literary depictions of Prague are still popular with readers today, claimed that “there is no other town to rival Prague in beauty”. The city of 100 spires, “Golden Prague” a jewel in the heart of the new Europe. Culture, tradition and a lively atmosphere present themselves in beautifully restored cultural monuments and former aristocratic palaces. The awe-inspiring panorama of the castle and St. Vitus Cathedral capture the heart of every visitor, a walk across Charles Bridge is a must… About destination CZECH REPUBLIC – BASIC FACTS Official title Czech Republic (Česká republika) Area 78,864 square kilometres Neighbouring countries Germany, Poland, Austria and Slovakia Population 10,300,000 inhabitants Capital Prague (1.2 million inhabitants) Other major cities Brno (388,596), Ostrava (325,827), Pilsen (171,908), Olomouc (106,278) Administrative language Czech Religion Predominantly Roman Catholic (39.2 %), Protestant (4.6%), Orthodox (3%), Atheist (39.8%) Political system Parliamentary democracy Currency Czech crown - CZK (Kč), 1 Kč = 100 h (haléřů) coins: 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 Kč banknotes: 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000 and 5000 Kč About destination CZECH REPUBLIC – BASIC FACTS Time zone Central European Time (CET), from April to October - summer time (GMT + 1, GMT + 2) Climate temperate, four seasons, a mix of ocean and inland climate, changeable winters, warm summers. -

Shakespeare Theatre Association Conference in Prague, Czech Republic

PRAGUE COMPANY INVITES YOU TO THE CITY OF A HUNDRED SPIRES PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC JANUARY 2019 PRECONFERENCE January 6-8, 2019 . 2019 STA CONFERENCE January 9-12, 2019 STA 2019 SPECS & WELCOME PACKET (more info coming later in 2018) STA Prague Conference 2019 Celebrate Shakespeare's global impact with the January 2019 Shakespeare Theatre Association Conference in Prague, Czech Republic. Prague Shakespeare Company is honored to host the STA 2019 Conference with a special focus on Shakespeare performance and production practices from around the world. Featuring exciting exchanges of artistic, managerial and educational methodologies between native and non-native English- speaking Shakespeare theatres and opportunites to attend performances in the evenings, STA 2019 Prague will offer valuable insights into new ways of thinking about and producing Shakespeare while allowing STA members to share their own proven practices with fellow Shakespeare artists from around the world. Highlights include a day of workshop sessions, panels and a performance at the National Theatre's historic Estates Theater (where Mozart premiered Don Giovanni in 1787) and a final banquet at the Lobkowicz Palace at Prague Castle. General Conference Itinerary: Pre-Conference - daily from 10am-4pm on 6, 7, 8 January 2019 Conference - daily from 10am-4pm on 9, 10, 11, 12 January 2019 Optional Evening performances (with purchase of ticket package) - 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 January 2019 Conference Day & Evening performance at the National Theatre's historic Estates Theater - 11 -

Download All Beautiful Sites

1,800 Beautiful Places This booklet contains all the Principle Features and Honorable Mentions of 25 Cities at CitiesBeautiful.org. The beautiful places are organized alphabetically by city. Copyright © 2016 Gilbert H. Castle, III – Page 1 of 26 BEAUTIFUL MAP PRINCIPLE FEATURES HONORABLE MENTIONS FACET ICON Oude Kerk (Old Church); St. Nicholas (Sint- Portugese Synagoge, Nieuwe Kerk, Westerkerk, Bible Epiphany Nicolaaskerk); Our Lord in the Attic (Ons' Lieve Heer op Museum (Bijbels Museum) Solder) Rijksmuseum, Stedelijk Museum, Maritime Museum Hermitage Amsterdam; Central Library (Openbare Mentoring (Scheepvaartmuseum) Bibliotheek), Cobra Museum Royal Palace (Koninklijk Paleis), Concertgebouw, Music Self-Fulfillment Building on the IJ (Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ) Including Hôtel de Ville aka Stopera Bimhuis Especially Noteworthy Canals/Streets -- Herengracht, Elegance Brouwersgracht, Keizersgracht, Oude Schans, etc.; Municipal Theatre (Stadsschouwburg) Magna Plaza (Postkantoor); Blue Bridge (Blauwbrug) Red Light District (De Wallen), Skinny Bridge (Magere De Gooyer Windmill (Molen De Gooyer), Chess Originality Brug), Cinema Museum (Filmmuseum) aka Eye Film Square (Max Euweplein) Institute Musée des Tropiques aka Tropenmuseum; Van Gogh Museum, Museum Het Rembrandthuis, NEMO Revelation Photography Museums -- Photography Museum Science Center Amsterdam, Museum Huis voor Fotografie Marseille Principal Squares --Dam, Rembrandtplein, Leidseplein, Grandeur etc.; Central Station (Centraal Station); Maison de la Berlage's Stock Exchange (Beurs van -

58Th Annual World Congress • ICA Social Program

th 58 Annual World Congress • ICA Social Program All tours include transfers to and from the Congress venue (HOTEL PYRAMIDA), entrance fees and a professional English-speaking guide. The link for registration for the social programme is: Guided Tours: http://www.gsymposion.com/event-detail/10/. Thursday, 2 June 2016 10.30 h. – 15.00 h. (10:30 am – 3:00 pm) SOCIAL PROGRAMME #1 PRAGUE CASTLE HALF-DAY CITY TOUR Prague Castle (Hradschin [Hradcany: hrad=castle]) is the largest castle complex in the world, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. Originally dating back to the 9th century, this landmark, which surrounds St. Veit’s Cathedral, bears the mark of each architectural and historical era that it has lived through. To this day it serves as the seat of the Czech state. In the picturesque Golden Lane, the little shops, built into the outer wall of the castle, which once housed the guards of the castle, cooks and alchemists to produce gold or an elixir of life, now house art, book and gift shops. Participants will be picked-up promptly by bus at the Congress venue (Hotel Pyramida) at 10:30 am to drive to the nearby Castle. During this tour, the participants will see Loreta (a large pilgrimage destination in Hradcany), the Prague Castle including the St. Vitus Cathedral, the Old Royal Palace and the Golden Lane. A break will be arranged (at an additional cost) in a typical Czech café. The cost per person for this tour is 50 € (excluding coffee break, which is an additional cost). -

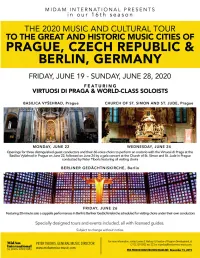

Published on February 11, 2019; Disregard All Previous Documents 1

Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 1 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 2 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 3 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 4 2020 Music Tour to Prague and Berlin Registration Deadline: November 15, 2020 Two performances in The Basilica Vyšehrad and The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude On Monday, June 22 and Wednesday, June 24 Mozart’s Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339 Earl Rivers, conductor College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati, Ohio And Director of Music Knox Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati, Ohio Virtuosi di Praga Oldřich Vlček, Artistic Director & World-class soloists PLUS Friday, June 26 An a cappella solo performance opportunity by visiting choirs In Berliner Gedächtniskirche A minimum of three groups must agree to perform for this concert to go forward. The Basilica Vyšehrad The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude Berliner Gedächtniskirche MidAm International, Inc. · 39 Broadway, Suite 3600 (36th FL) · New York, NY 10006 Tel. (212) 239-0205 · Fax (212) 563-5587 · www.midamerica-music.com Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 5 2020 MUSIC TOUR TO PRAGUE AND BERLIN: Itinerary Day 1 – Friday, June 19, 2020 – Arrive Prague • Arrive in Prague. MidAm International, Inc. staff and The Columbus Welcome Management staff will meet you at the airport and transfer you to Hotel Don Giovanni (http://www.hotelgiovanni.cz/en) for check-in. -

Hradcany 16 Lesser Town 62 Old Town and Jewish

HRADCANY 16 The Emperor and his City: Charles IV 76 Franz Kafka Museum 78 Prague Castle 18 Kampa Island, Vltava 80 Prague Castle: St Vitus Cathedral 26 Kampa Museum 82 "Saint Wenceslas, Mostecka Street 84 Duke of the Czech Land" 34 Lesser Town Square 86 Prague Castle: Old Royal Palace 36 St Nicholas Church, Lesser Town 88 Prague Castle: St George's Basilica 38 St Thomas, St Joseph 90 Prague Castle: Golden Lane 40 Nerudova Street 92 Classic of Literary Modernism: Symbols and Miracles 94 Franz Kafka 42 New Castle Stairs 96 Prague Castle: Belvedere Palace 44 Wallenstein Palace 98 Hradcany Square 46 A Vision of Prague: Palace Gardens 100 Collections of the National Gallery Lobkowicz Palace 102 on the Hradcany 50 Vrtba Palace, Vrtba Garden 104 Loreto Sanctuary 52 Church of Our Lady Victorious 106 Reformation and Wars of Religion 54 Petrin Hill 108 Novy svet, Pohorelec 56 Strahov Monastery 58 OLD TOWN AND JEWISH Author, Civil Rights Activist, President: QUARTER 110 Vaclav Havel 60 J Knights of the Cross Square 112 LESSER TOWN 62 Clementinum 114 My Quay, my Music, my Fatherland: The River, the King, his Wife and Smetana 116 her Lover 64 Charles Street 118 Charles Bridge 66 Clam-Gallas Palace 120 http://d-nb.info/1021832235 Prague Puppetry: The Emperor and his Banker 178 ENVIRONS 226 Artists on a String 122 Old Jewish Cemetery • 180 Church of St Giles 124 Pinkas Synagogue 182 Letna Park 228 Gall Town 126 Rudolfinum 184 Trade Fair Palace 230 Estates Theater 128 Museum of Decorative Arts 186 Royal Enclosure, Exhibition Grounds 232 Carolinum 130 -

Nelahozeves Castle and Lobkowicz Palace Our Current Security System at Nelahozeves Castle and in the Lobkowicz Palace with Task More Sophisticated Technology

1 The Lobkowicz Collections OVERVIEW & SPECIAL PROJECTS 2018 3 Welcome Message from the Director Contents Thank you for your interest in the Lobkowicz and corporate donors, members, friends and The Collections Collections. For the past 20 years, Lobkowicz visitors from around the world. We greatly About the Lobkowicz Collections 6 Collections o.p.s.*, a non-profit organization appreciate this support and look forward to Highlights 7 registered in the Czech Republic, has been building new relationships as we plan our All is Lost... And Regained 8 working to preserve, protect and share with path for the future. Architecture 9 the public the magnificent art, artifacts and This document presents a brief overview Portraits and Decorative Arts 10 buildings returned to the Lobkowicz family of our past accomplishments, current activi- Furniture and Music 11 in restitution after the Velvet Revolution of ties and a selection of priority projects. Its The Lobkowicz Library and Archives 12 1989. purpose is to provide background and con- Through bold vision, careful planning text for the numerous initiatives underway. Activities and great determination, Lobkowicz Col- We hope this information will stimulate The Mission of Lobkowicz Collections o. p. s. 14 lections o.p.s. has opened exhibitions to further interest and engagement from the The Activities of Lobkowicz Collections o. p. s. 15 thousands of visitors, making tens of thou- general public, friends and benefactors in our American Friends for the Preservation of Czech Culture 16 sands of cultural objects available for scholars mission to make the Lobkowicz Collections Educational Programs 17 and the general public. -

Summary FINAL Copy

19 – 21 JUNE 2018 PRAGUE EUROPEAN SUMMIT SUMMARY LOBKOWICZ PALACE & CZERNIN PALACE Základní varianty značky Úřadu vlády České republiky: Of�ice of the Government of the Czech Republic ORGANIZERS Of�ice of the Government of the Czech Republic STRATEGIC PARTNER Of�ice of the Government of the Czech Republic MAIN INSTITUTIONAL PARTNER MAIN INSTITUTIONAL PARTNER INSTITUTIONAL PARTNER Colors of O ci l Logo BLUE GREY BLACK CMYK 070-000-020-000 CMYK 000-000-000-060 CMYK 000-000-000-100 P ntone Co ted 3115 C P ntone Cool Gr y 5 C P ntone Bl ck C P ntone Unco ted 3105 U P ntone Cool Gr y 5 U P ntone Bl ck U RGB 003-191-215 RGB 102-102-102 RGB 000-000-000 WEB #03BFD7 WEB #666666 WEB #000000 MAIN PARTNER MAIN PARTNER MAIN PARTNER PARTNER PARTNER SUPPORTER Prague SUPPORTER SUPPORTER SUPPORTER PRAGUE TALKS PARTNER FOREWORD Dear Reader, we are proud to present to you summary of the fourth annual Prague European Summit conference. At the time when the sense of acute crisis of European political community had finally withered but uncertainty remained as the EU was to become a union of one less, trust in the public institutions was challenged across the continent, social paranoia empowered the prophets of easy solutions to complex problems, disinformat on campaigns posed ever increasing challenges that the external environment submitted no shortage of either, an illustrious crowd of statesmen, public servants, academics, businessmen, journalists and young leaders gathered in Prague again to engage in a frank debate about which direction the EU should take to advance the European idea and the vision of peace and prosperity on the continent. -

The Prague Card Offers You This

The Prague Card offers you this: AIRPORT EXPRESS BUS FREE ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK MEMORIAL FREE ENTRY ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK MUSEUM FREE ENTRY ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATORY FREE ENTRY AUDIOGUIDE TOURS - 30% BEDŘICH SMETANA MUSEUM FREE ENTRY BEER MUSEUM - 30% BÍLEK VILLA FREE ENTRY BLACK LIGHT THEATRE - 30% BRICK GATE FREE ENTRY BUS TOUR HISTORICAL PRAGUE FREE BUS TRIPS OUT OF PRAGUE - 25% CHAPEL OF THE HOLY CROSS -20% CHARLES BRIDGE MUSEUM - 50% CHOCO STORY - 30% CHOCOLATE HOUSE - 50% CITY OF PRAGUE MUSEUM FREE ENTRY COMENIUS PEDAGOGICAL FREE ENTRY MUSEUM CONCERTS AT ST.NICHOLAS - 100 Kč CHURCH CONVENT OF ST.AGNES OF FREE ENTRY BOHEMIA CTĚNICE CASTLE FREE ENTRY CZECH MUSEUM OF MUSIC FREE ENTRY DALIBORKA TOWER FREE ENTRY DINNER NIGHT CRUISE - 30% FILM SPECIAL EFFECTS MUSEUM - 25% FOLKLORE GARDEN -25% FRANZ KAFKA MUSEUM - 20% GALLERY CAFÉ -15% GHOST AND LEGENDS MUSEUM - 30% GHOSTS & LEGENDS OF OLD - 40% TOWN GOLDEN LANE FREE ENTRY GOLDEN RING HOUSE FREE ENTRY GOTHIC CELLAR FREE ENTRY HARD ROCK CAFE FREE DESERT with Main Course HOP ON - HOP OFF - 25% ICE PUB 2 free drinks JEWISH MUSEUM FREE KINSKÝ SUMMER HOUSE FREE ENTRY KLEMENTINUM - 25% KNIGHTS OF THE CROSS - 100 Kč CONCERTS LAPIDARIUM FREE ENTRY LESSER TOWN BRIDGE TOWERS - 50% LOBKOWICZ PALACE - 50% LORETO PRAGUE - 30 Kč LUNCH RIVER CRUISE - 25% MODEL OF PRAGUE - 40% MOZART DINNER - 20% MUCHA MUSEUM - 20% MUNICIPAL HOUSE - 15% MUNICIPAL LIBRARY FREE ENTRY MUSÉE GREVIN - 30% MUSEUM OF ALCHEMISTS - 20% MUSEUM OF DECORATIVE ARTS FREE ENTRY MUSEUM OF LEGO - 40% NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM FREE ENTRY NATIONAL MEMORIAL VÍTKOV -

Prague European Summit Day One, 19 June 2018 Venue: Lobkowicz Palace

Prague European Summit Day One, 19 June 2018 venue: Lobkowicz Palace 12:15 – 13:00 Registration, coffee and refreshment 13:00 – 13:15 Words of Welcome: Vladimír Bartovic, Director, EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy Ondřej Ditrych, Director, Institute of International Relations Prague 13:15 – 14:00 Key-Note Address. EU: Ever Closer to the Citizens? Andrej Babiš, Prime Minister of the Czech Republic Věra Jourová, European Commissioner, Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Plenary Session: Populism and Demagogy: Are We Really out of the Woods? The year 2017 was dubbed by some, perhaps too quickly, as the year that populist parties were defeated in crucial elections, especially with the defeat of Marine Le Pen and the realization that BREXIT will be a slow and mostly painful process. Is the influence of populist parties on the decline? Have the underlying factors of their rise been identified, and are mainstream politicians acting upon them? What is the danger of traditional parties appropriating themselves the rhetoric and sometimes even policies from these populist movements? Rosa Balfour, Senior Fellow, Europe programme, German Marshall Fund of the US Yves Bertoncini, President of the European Movement-France Josip Brkić, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina Monica Frassoni, Co-Chair, European Green Party Isabell Hoffmann, Senior Expert, Head of the Research Project eupinions, Bertelsmann Foundation Chair: Ondřej Ditrych, Director, Institute of International Relations Prague 15:00 – 15:30 Coffee break 1 15:30 – 17:00 Breakout Sessions: Session A: Quo Vadis European Neighbourhood? The European Neighbourhood Policy was conceived with the aim of creating a ring of peaceful, stable and prosperous states at the EU’s borders.