Libuše's Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploration of Chemical Space by Machine Learning

Skolkovo Instutute of Science and Technology EXPLORATION OF CHEMICAL SPACE BY MACHINE LEARNING Doctoral Thesis by Sergey Sosnin Doctoral Program in Computational and Data Science and Engineering Supervisor Vice-President for Artificial Intelligence and Mathematical Modelling, Professor, Maxim Fedorov Moscow – 2020 © Sergey Sosnin, 2020 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis was carried out by myself at Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Moscow, except where due acknowledgement is made, and has not been submitted for any other degree. Candidate: Sergey Sosnin Supervisor (Prof. Maxim V. Fedorov) 2 EXPLORATION OF CHEMICAL SPACE BY MACHINE LEARNING by Sergey Sosnin Submitted to the Center for Computational and Data-Intensive Science and Engineering and Innovation on September 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctoral Program in Computational and Data Science and Engineering Abstract The enormous size of potentially reachable chemical space is a challenge for chemists who develop new drugs and materials. It was estimated as 1060 and, given such large numbers, there is no way to analyze chemical space by brute-force search. However, the extensive development of techniques for data analysis provides a basis to create methods and tools for the AI-inspired exploration of chemical space. Deep learning revolutionized many areas of science and technology in recent years, i.e., computer vision, natural language processing, and machine translation. However, the potential of application of these methods for solving chemoinformatics challenges has not been fully realized yet. In this research, we developed several methods and tools to probe chemical space for predictions of properties of organic compounds as well as for visualizing regions of chemical space and for the sampling of new compounds. -

Prague Participatory Budget

PRAGUE PARTICIPATORY BUDGET CASE STUDY REPORT & ANALYSIS Prepared by AGORA CE Author: Vojtěch Černý The publication is a result of the project ”Participatory Budgeting for Sustainable Development of V4 Capital Cities” supported by International Visegrad Fund. Project coordinator: Collegium Civitas, Warsaw, Poland Partners of the project: Mindspace - Budapest, Agora CE - Prague, Utopia - Bratislava, Inicjatywy - Warsaw 2 This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license 3 This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the IVF cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. CONTENTS Preface ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Prague – main facts about the city .......................................................................................................... 6 Origins of PB in Prague ............................................................................................................................ 8 Development of the Participative Budget(s) in Prague ......................................................................... 15 Preparation of the PB procedure ...................................................................................................... 16 Participatory budgeting ..................................................................................................................... 19 -

Dokument B.Indd

část B - nová infrastruktura Rozvoj linek PID v Praze 2019-2029 Rozvoj linek PID 2019-2029 část B (nová infrastruktura) © Odbor městské dopravy, Ropid 2018 sazba a design: Ing. arch. Václav Brejška, provozní bilance: David Marek výpočet výkonů: Ing. Blanka Brožová strategie snižování emisí autobusů: Ing. Jan Barchánek zástupce vedoucího projektu: Ing. Martin Šubrt vedoucí projektu: Ing. Martin Fafejta 3 Obsah Úvod Dokument „Rozvoj linek PID v Praze 2019-2029“ zachycuje předpokládaný vývoj linkového vedení Úvod 5 PID na území hl. m. Prahy v následujících deseti letech. Tento vývoj je zpracován v kontextu realizací no- vých projektů na síti kolejové dopravy, v souvislosti s další komerční a bytovou zástavbou v jednotlivých Vysvětlivky, symboly a struktura hesel 6 lokalitách Prahy, s předpokládaným růstem přepravní poptávky a v řadě míst reaguje i na výhledové po- Opatření B.01-B.19 – Úvod k novým infrastrukturním projektům 9 žadavky městských částí. Základním cílem dokumentu je poskytnout městské samosprávě i veřejnosti podrobnější před- Opatření B.01 - TT Levského - Libuš, Autobusové obratiště Šabatka 11 stavu o tom, jakou podobu hromadné dopravy mohou v okolí svého bydliště očekávat po dokončení no- vých tras metra, tratí tramvají, modernizací železničních tratí a po dostavbě dalších obytných a adminis- Opatření B.02 - Tramvajová smyčka Depo Hostivař 17 trativních celků. Opatření B.03 - TT Divoká Šárka - Dědina 21 Dokument si dále klade za cíl popsat, jaký objem hromadné dopravy bude na nových úsecích možné očekávat. Bude sloužit jako podklad pro výpočet vývoje objemu objednaných vozokilometrů PID Opatření B.04 - TT Sídliště Barrandov - Slivenec, Železniční trať Smíchov - Radotín 27 na území hl. -

Twenty Years After the Iron Curtain: the Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010

Twenty Years after the Iron Curtain: The Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010 Assistant Professor at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic n November of last year, the Czech Republic commemorated the fall of the communist regime in I Czechoslovakia, which occurred twenty years prior.1 The twentieth anniversary invites thoughts, many times troubling, on how far the Czechs have advanced on their path from a totalitarian regime to a pluralistic democracy. This lecture summarizes and evaluates the process of democratization of the Czech Republic’s political institutions, its transition from a centrally planned economy to a free market economy, and the transformation of its civil society. Although the political and economic transitions have been largely accomplished, democratization of Czech civil society is a road yet to be successfully traveled. This lecture primarily focuses on why this transformation from a closed to a truly open and autonomous civil society unburdened with the communist past has failed, been incomplete, or faced numerous roadblocks. HISTORY The Czech Republic was formerly the Czechoslovak Republic. It was established in 1918 thanks to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his strong advocacy for the self-determination of new nations coming out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the World War I. Although Czechoslovakia was based on the concept of Czech nationhood, the new nation-state of fifteen-million people was actually multi- ethnic, consisting of people from the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia), Slovakia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia (today’s Ukraine), and approximately three million ethnic Germans. Since especially the Sudeten Germans did not join Czechoslovakia by means of self-determination, the nation- state endorsed the policy of cultural pluralism, granting recognition to the various ethnicities present on its soil. -

8Th RD 50 Workshop, Prague, 25 – 28 June 2006 Venue: CTU in Prague – Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technicka 4, Praha 6 - Dejvice, Czech Republic

8th RD 50 Workshop, Prague, 25 – 28 June 2006 Venue: CTU in Prague – Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technicka 4, Praha 6 - Dejvice, Czech Republic ACCOMMODATION FORM Please type or fill in this form in CAPITALS and mail or fax to this address: CTU in Prague, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technicka 4, 166 07 Praha 6 - Dejvice, Czech Republic Fax: +420 224 310 292, Phone: +420 224 355 688, E-mail: [email protected] Mr. Mrs. Ms. Surname : First name: Address: City: Country: Post code/ZIP: Phone: Fax: E-mail: RESERVATION OF ACCOMMODATION: Arrival: date Departure: date Nights total: Your chosen accommodation cannot be guaranteed unless the accommodation form is received by April 30, 2006. Hotel assignment will be made on the first-come, first-serve basis, therefore it is advisable to make reservation of accommodation as soon as possible. The prices are valid if your order is sent to the above-mentioned address, only (not to the hotel). Hotel/hostel - category: Single Room Double Room # Nights total Amount Due 1. Palace ***** 220 EUR 240 EUR × = EUR 2. Diplomat **** 150 EUR 170 EUR × = EUR 3. Pyramida **** 100 EUR 120 EUR × = EUR 4. Novomestsky hotel *** 90 EUR 110 EUR × = EUR 5. Hotel Denisa *** 75 EUR 95 EUR × = EUR 6. Hotel Krystal *** 55 EUR 65 EUR × = EUR 7. Masarykova kolej *** 45 EUR 55 EUR × = EUR 8. Student hostel ** 28 EUR 38 EUR × = EUR # shared with accompanying person participant of the workshop (name): The price of accommodation includes bed, breakfast (except student hostels **), city charges and VAT. Hotel voucher will be mailed to you upon receipt of payment (minimum one night deposit is required, the balance will be paid at the workshop registration desk). -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Prague Guide Prague Guide Money

PRAGUE GUIDE PRAGUE GUIDE MONEY Currency: Koruna (crown), 1 Kč = 100 haléř Domestic beer (0.5 liter, draught) – 25-45 CZK Essential Information Souvenir t-shirt – 150-200 CZK Money 3 You can exchange your currency at any bank and Gasoline (1 liter) – 36 CZK most tourist offices. Avoid the unofficial money Hostels (average price/night) – 400-600 CZK Communication 4 The capital of the Czech Republic is also called exchange offices; most of them will only scam 4* hotel (average price/night) – 2000-3000 CZK the City of One Hundred Spires. The metrop- you. Always ask first about the exchange rate. Car-hire (medium-sized car/day) – 1000 CZK Holidays 5 olis is well-known for its amazing mix of many Credit cards are accepted at most stores and Taxi from the airport to the city centre – restaurants – identified by the relevant stickers 550-700 CZK Transportation 6 architectural styles, both old and new. Prague is also one of the best destinations in Europe on the door. You will need cash for the smaller Tipping Food 8 for history buffs – literally every street here has businesses. Larger stores and hypermarkets also witnessed some historical event. accept Euro, although you’ll get the change back Tipping is welcomed, especially in bars, restau- Events During The Year 9 The city center, with its churches, bridges, old in crowns and the exchange rate is generally un- rants and by taxi drivers. The usual amount is houses and cobbled alleys, was left nearly un- favorable. 5-10% of the bill or you can round up to the next 10 Things to do damaged by the WWII and, as such, has a ten or twenty crowns. -

Famous People from Czech Republic

2018 R MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Tennessee Academic Standards 2018 EDUCATION CURRICULUM GUIDE MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Celebrates the Czech Republic in 2018 Celebrating the Czech Republic is the year-long focus of the 2018 Memphis in May International Festival. The Czech Republic is the twelfth European country to be honored in the festival’s history, and its selection by Memphis in May International Festival coincides with their celebration of 100 years as an independent nation, beginning as Czechoslovakia in 1918. The Czech Republic is a nation with 10 million inhabitants, situated in the middle of Europe, with Germany, Austria, Slovakia and Poland as its neighbors. Known for its rich historical and cultural heritage, more than a thousand years of Czech history has produced over 2,000 castles, chateaux, and fortresses. The country resonates with beautiful landscapes, including a chain of mountains on the border, deep forests, refreshing lakes, as well as architectural and urban masterpieces. Its capital city of Prague is known for stunning architecture and welcoming people, and is the fifth most- visited city in Europe as a result. The late twentieth century saw the Czech Republic rise as one of the youngest and strongest members of today’s European Union and NATO. Interestingly, the Czech Republic is known for peaceful transitions; from the Velvet Revolution in which they left Communism behind in 1989, to the Velvet Divorce in which they parted ways with Slovakia in 1993. Boasting the lowest unemployment rate in the European Union, the Czech Republic’s stable economy is supported by robust exports, chiefly in the automotive and technology sectors, with close economic ties to Germany and their former countrymen in Slovakia. -

Název Obce Kód Obce Městský Obvod V Praze Obvod Podle Zákona Č. 36

Městský obvod Kód Kód Počet Počet Kód části Kód části Domy k Název obce Kód obce v Praze obvod podle zákona č. městského Městská část městské Název části obce Název části obce dílu obyvatel k obyvatel k obce obce dílu 1. 3. 2001 36/1960 Sb. obvodu části 3. 3. 1991 1. 3. 2001 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Holešovice 490067 Holešovice (Praha 1) 414956 000 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Hradčany 490075 Hradčany (Praha 1) 400041 1 166 1 056 132 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Josefov 127001 Josefov 127001 2 354 1 997 66 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Malá Strana 490121 Malá Strana (Praha 1) 400033 6 364 5 264 409 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Nové Město 490148 Nové Město (Praha 1) 400025 19 666 15 733 850 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Staré Město 400017 Staré Město 400017 13 040 10 531 627 Praha 554782 Praha 1 Praha 1 500054 Vinohrady 490229 Vinohrady (Praha 1) 400050 000 Praha 554782 Praha 2 Praha 2 500089 Nové Město 490148 Nové Město (Praha 2) 400068 15 325 12 380 550 Praha 554782 Praha 2 Praha 2 500089 Nusle 490156 Nusle (Praha 2) 400084 4 867 4 311 191 Praha 554782 Praha 2 Praha 2 500089 Vinohrady 490229 Vinohrady (Praha 2) 400076 39 629 32 581 1 359 Praha 554782 Praha 2 Praha 2 500089 Vyšehrad 127302 Vyšehrad 127302 2 052 1 731 114 Praha 554782 Praha 3 Praha 3 500097 Strašnice 490181 Strašnice (Praha 3) 400122 241 Praha 554782 Praha 3 Praha 3 500097 Vinohrady 490229 Vinohrady (Praha 3) 400114 20 636 17 431 597 Praha 554782 Praha 3 Praha 3 500097 Vysočany 490245 Vysočany (Praha 3) 400092 661 Praha 554782 -

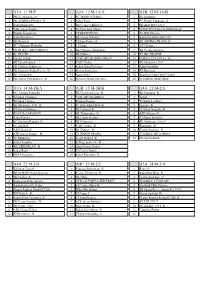

A1a 11 M-P A2a 12 M-1A/A A2b 13 M-1A/B A3a 14 M-1B/A A3b 15 M-1B

A1A 11 M-P A2A 12 M-1A/A A2B 13 M-1A/B 1 FK Újezd nad Lesy 1 FC TEMPO PRAHA 1 SK Modřany 2 FK ADMIRA PRAHA B 2 Sokol Troja 2 FC Přední Kopanina B 3 Sokol Kolovraty 3 SK Čechie Uhříněves 3 FK ZLÍCHOV 1914 4 AFK Slavoj Podolí 4 FC Háje Jižní Město 4 SPORTOVNÍ KLUB ZBRASLAV 5 Přední Kopanina 5 TJ BŘEZINĚVES 5 TJ AFK Slivenec 6 Sokol Královice 6 SK Union Vršovice 6 Sportovní klub Libuš 838 7 SK Hostivař 7 TJ Kyje Praha 14 7 SK ARITMA PRAHA B 8 SC Olympia Radotín 8 TJ Praga 8 1999 Praha 9 FK DUKLA JIŽNÍ MĚSTO 9 SK Viktoria Štěrboholy 9 SK Čechie Smíchov 10 FC ZLIČÍN 10 SK Ďáblice 10 TJ ABC BRANÍK 11 Uhelné sklady 11 TJ SPARTAK HRDLOŘEZY 11 LOKO VLTAVÍN z.s. B 12 SK Újezd Praha 4 12 ČAFC Praha 12 SK Střešovice 1911 13 FK Viktoria Žižkov a.s. 13 Sokol Dolní Počernice 13 Sokol Stodůlky 14 FK Motorlet Praha B s.r.o. B 14 Slovan Kunratice 14 FK Řeporyje 15 SK Třeboradice 15 Spoje Praha 15 Sportovní klub Dolní Chabry 16 FK Slavoj Vyšehrad a.s. B 16 Xaverov Horní Počernice 16 TJ SOKOL NEBUŠICE A3A 14 M-1B/A A3B 15 M-1B/B A4A 21 M-2/A 1 FC Tempo Praha B 1 FK Újezd nad Lesy B 1 SK Modřany B 2 TJ Sokol Cholupice 2 TJ SPARTAK KBELY 2 Točná 3 TJ Sokol Lipence 3 Partisan Prague 3 TJ Sokol Lochkov 4 SK Střešovice 1911 B 4 FC Háje Jižní Město B 4 Lipence B 5 TJ Slovan Bohnice 5 SK Hostivař B 5 TJ Sokol Nebušice B 6 TJ AVIA ČAKOVICE 6 SK Třeboradice B 6 AFK Slivenec B 7 Sokol Písnice 7 FK Union Strašnice 7 TJ Slavoj Suchdol 8 SC Olympia Radotín B 8 FK Klánovice 8 SK Střešovice 1911 C 9 FC Zličín B 9 ČAFC Praha B 9 Řeporyje B 10 ABC Braník B 10 SK Ďáblice -

Delegates Handbook Contents

Delegates Handbook Contents Introduction 5 Czech Republic 6 - Prague 7 Daily Events and Schedule 10 Venue 13 Accreditation/ Registration 20 Facilities and Services 21 - Registration/Information Desk 21 - Catering & Coffee Breaks 21 - Business Center 21 - Additional Meeting Room 21 - Network 22 - Working Language and Interpretation 22 Accommodation 23 Transportation 24 - Airport Travel Transportation 24 - Prague Transportation 25 3 Tourism in Prague 27 Introduction - Old Town Hall with Astronomical Clock 27 - Prague Castle, St. Vitus Cathedral 28 - Charles Bridge 29 As Host Country of the XLII Antarctic Treaty - Petřín Lookout tower 30 Consultative Meeting (ATCM XLII), the Czech - Vyšehrad 30 Republic would like to give a warm welcome - Infant Jesus of Prague 31 to the Representatives of the Consultative and - Gardens and Museums 31 Non-Consultative Parties, Observers, Antarctic Treaty System bodies and Experts who participate in this Practical Information 32 meeting in Prague. - Currency, Tipping 32 This handbook contains detailed information on the - Time Zone 33 arrangements of the Meeting and useful information - Climate 33 about your stay in Prague, including the meeting - Communication and Network 34 schedule, venues and facilities, logistic services, etc. It is - Electricity 34 recommended to read the Handbook in advance to help - Health and Water Supply 35 you organize your stay. More information is available - Smoking 35 at the ATCM XLII website: www.atcm42-prague.cz. - Opening Hours of Shops 35 ATS Contacts 36 HCS Contacts 36 4 5 the European Union (EU), NATO, the OECD, the United Nations, the OSCE, and the Council of Europe. The Czech Republic boasts 12 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. -

PDF Download

15 November 2019 ISSN: 2560-1628 2019 No. 9 WORKING PAPER Development of Czech-Chinese diplomatic and economic relationships after 1949 Ing. Renata Čuhlová, Ph.D, BA (Hons) Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 [email protected] china-cee.eu Development of Czech-Chinese diplomatic and economic relationships after 1949 Abstract The cooperation between Czechia and PRC went through an extensive development, often in the context of contemporary political changes. The paper analyses the impact of bilateral diplomacy on the intensity of trade and investment exchange and it investigates the mutual attractiveness of the markets. Based on this analysis, the third part focuses on the existing problems, especially trade deficit, and it highlights the potential fields for further strengthening of partnership. The methodology framework is based on empirical approach and it presents a comprehensive case study mapping the evolution of Czech-Chinese dialogue in terms of diplomacy, economic exchange and existence of supporting organizations. Keywords: Czech-Chinese relationships, bilateral investment, diplomacy, economic and trade cooperation Introduction Despite of the transcontinental geographic distance and intercultural differences including languages barrier, Czechia, a Central European country, formerly known as Czechoslovakia until 1993, and People´s Republic of China (PRC) have experienced a great deal of discontinuity during last decades starting from big expectations in 1950s based on past time investment trade tradition during 1920s-1930s through very cold estrangement till the current strong partnership. The approach of the Czechia towards PRC has rapidly evolved and changed through the history, mainly due to contemporary political forces.