Roswell and Walker AFB Closure: History, Analysis, and Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

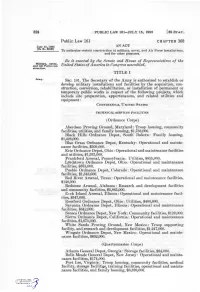

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Join Today! Year (January Through December), and Can Be Paid for Through Paypal Or by Check

If you love all things aviation, World War II history, and Join now by contacting the Museum (575-347-2464, online military history, your membership opens the door to all at www.wafbmuseum.org) or fill out the attached form and sorts of fun and education. We are a private museum, with send it, with your check, to Walker Aviation Museum, P.O. no other source of revenue, other than the support from Box 4080, Roswell, NM 88202. those who appreciate what we have done to create the Museum. We keep our doors open with donations. Without your support and those in our aviation community, we are not sustainable, so sign up for a membership at the level you wish contribute. All memberships are for the calendar Join today! year (January through December), and can be paid for through PayPal or by check. Charter, Life, and Corporate Walker Aviation memberships can be paid quarterly through PayPal. Museum Foundation Join Us! Membership & Donor Program Mailing Address: Individual Membership PO Box 4080 $25.00 annually Roswell, NM 88202 Charter Membership Physical Address: $1,000 one time charge 1 Jerry Smith Circle, Includes membership for life and a permanent plaque Roswell, NM 88203 honoring your contribution (in the airport terminal) Open Mon-Sat 10:00 a.m. - 3:30 p.m. Life Membership $500 one time charge www.wafbmuseum.org [email protected] Corporate or Group Membership $500 Annually Advertising and publicity & sponsorship in the Museum 575-347-2464 Membership Application Yes! I would love to help the Walker Aviation Museum and join as a member. -

16004491.Pdf

-'DEFENSE ATOMIC SUPPORT AGENCY Sandia Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico ,L/PE - 175 Hi%&UhIiT~ SAIdDIA BASE ALBu2umxJE, la$ mXIc0 7 October 1960 This is to cert!e tlmt during the TDY period at this station, Govement Guarters were available and Goverrrment Fessing facilities were not availzble for the following mmoers of I%Ki: Colonel &w, Og~arHe USA Pi3 jor Andm~n,Qaude T. USAF Lt. Colonel fsderacn, George R. USAF Doctor lrndMvrsj could Re Doctor Acdrem, Howard L. USPIG Colonel ksMlla stephen G. USA Colonel Ayars, Laurence S. USAF Lt. Colonel Bec~ew~ki,Zbignie~ J. USAF Lt. Colonel BaMinp, George S., Jr. USAF bjor Barlow, Lundie I:., Jr. UMG Ckmzzder m, h3.llian E. USPHS Ujor Gentley, Jack C. UskF Colonel Sess, Ceroge C. , WAF Docto2 Eethard, 2. F. Lt. c=Jlonel Eayer, David H., USfiF hejor Bittick, Paul, Jr. USAF COlOIle3. Forah, hUlhm N. USAF &;tail? Boulerman, :!alter I!. USAF Comander hwers, Jesse L. USN Cz?trin Brovm, Benjamin H, USAF Ca?tain Bunstock, lrKulam H. USAF Colonel Campbell, lkul A. USAF Colonel Caples, Joseph T. USA Colonel. Collins, CleM J. USA rmctor Collins, Vincent P. X. Colonel c0nner#, Joseph A. USAF Cx:kain ktis, Sidney H. USAF Lt. Colonel Dauer, hxmll USA Colonel kvis, Paul w, USAF Captsir: Deranian, Paul UShT Loctcir Dllle, J. Robert Captain Duffher, Gerald J. USN hctor Duguidp Xobert H. kptain arly, klarren L. use Ca?,kin Endera, Iamnce J. USAF Colonel hspey, James G., Jr. USAF’ & . Farber, Sheldon USNR Caifain Farmer, C. D. USAF Ivajor Fltzpatrick, Jack C. USA Colonel FYxdtt, Nchard s. -

The Missile Plains: Frontline of America's Cold

The Missile Plains: Frontline of America’s Cold War Historic Resource Study Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, South Dakota Prepared for United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Midwest Regional Office 2003 Prepared under the supervision of: Dr. Jeffrey A. Engel, Principal Investigator Authors: Mead & Hunt, Inc. Christina Slattery Mary Ebeling Erin Pogany Amy R. Squitieri Recommended: Site Manager, Minuteman Missile National Historic Site Date Superintendent, Badlands National Park Date Concurred: Chief, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Associate Regional Director Date Cultural Resources and Stewardship Partnerships Approved: Regional Director Date Midwest Region Minuteman Missile National Historic Site Historic Resource Study Table of Contents List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................ iv List of Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................viii Preface....................................................................................................................................x Introduction ..........................................................................................................................xi Establishment and Purpose................................................................................................................... xi Geographic Location ............................................................................................................................ -

Brigadier General Eugene W. Gauch Jr

BRIGADIER GENERAL EUGENE W. GAUCH JR. Retired Sep. 1, 1975. Brigadier General Eugene W. Gauch Jr., is director of automated mobility requirements, Deputy Chief of Staff, Plans and Operations, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, with duty station at Langley Air Force Base, Va. General Gauch was born in 1922, in Newark, N.J. He graduated from Jefferson High School in Elizabeth, N.J., in 1941, attended Syracuse University, and is a graduate of the National War College, 1969. In March 1943 he entered active military service with the Army Air Corps and as an aviation cadet attended pilot training and graduated as a flight officer from Pampa Army Air Force Base, Texas, in November 1944. After bomber crew training assignments at Liberal, Kan.; Tonapah, Nev.; and Walla Walla, Wash., he went to Okinawa and served with the 346th and 22d Bombardment Groups as a B-29 pilot. In June 1948 General Gauch returned to the United States and was assigned to the Air Training Command as an instructor for aviation cadets in single- and twin- engine aircraft at Randolph and Perrin Air Force bases, Texas, and Barksdale Air Force Base, La. In July 1949 he was assigned to the 509th Bombardment Group of the Strategic Air Command, Walker Air Force Base, N.M. He next was assigned to the Military Airlift Command in Japan; however, with the onset of the Korean War, he was transferred to the 19th Bombardment Group at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, and flew B-29 combat missions over Korea for which he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters. -

Historical Handbook of NGA Leaders

Contents Introduction . i Leader Biographies . ii Tables National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Directors . 58 National Imagery and Mapping Agency and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Deputy Directors . 59 Defense Mapping Agency Directors . 60 Defense Mapping Agency Deputy Directors . 61 Defense Mapping Agency Directors, Management and Technology . 62 National Photographic Interpretation Center Directors . 63 Central Imagery Office Directors . 64 Defense Dissemination Program Office Directors . 65 List of Acronyms . 66 Index . 68 • ii • Introduction Wisdom has it that you cannot tell the players without a program. You now have a program. We designed this Historical Handbook of National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Leaders as a useful reference work for anyone who needs fundamental information on the leaders of the NGA. We have included those colleagues over the years who directed the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and the component agencies and services that came together to initiate NGA-NIMA history in 1996. The NGA History Program Staff did not celebrate these individuals in this setting, although in reading any of these short biographies you will quickly realize that we have much to celebrate. Rather, this practical book is designed to permit anyone to reach back for leadership information to satisfy any personal or professional requirement from analysis, to heritage, to speechwriting, to retirement ceremonies, to report composition, and on into an endless array of possible tasks that need support in this way. We also intend to use this book to inform the public, especially young people and students, about the nature of the people who brought NGA to its present state of expertise. -

166 Public Law 86-500-.June 8, 1960 [74 Stat

166 PUBLIC LAW 86-500-.JUNE 8, 1960 [74 STAT. Public Law 86-500 June 8. 1960 AN ACT [H» R. 10777] To authorize certain construction at military installation!^, and for other pnriwses. He it enacted hy the Hemite and House of Representatives of the 8tfiction^'Acf°^ I'raited States of America in Congress assemoJed, I960. TITLE I ''^^^* SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army may establish or develop military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, con- \'erting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public works, including site preparation, appurtenances, utilities, and equip ment, for the following projects: INSIDE THE UNITED STATES I'ECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Training facilities, medical facilities, and utilities, $6,221,000. Benicia Arsenal, California: Utilities, $337,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Utilities and ground improvements, $353,000. Picatinny Arsenal, New Jersey: Research, development, and test facilities, $850,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, Colorado: Operational facilities, $369,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Community facilities and utilities, $1,000,000. Umatilla Ordnance Depot, Oregon: Utilities and ground improve ments, $319,000. Watertow^n Arsenal, Massachusetts: Research, development, and test facilities, $1,849,000. White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico: Operational facilities and utilities, $1,2'33,000. (Quartermaster Corps) Fort Lee, Virginia: Administrative facilities and utilities, $577,000. Atlanta General Depot, Georgia: Maintenance facilities, $365,000. New Cumberland General Depot, Pennsylvania: Operational facili ties, $89,000. Richmond Quartermaster Depot, Virginia: Administrative facili ties, $478,000. Sharpe General Depot, California: Maintenance facilities, $218,000. (Chemical Corps) Army Chemical Center, Maryland: Operational facilities and com munity facilities, $843,000. -

Georgetown University Alumni Magazine

Georgetown University Alumni Magazine Volume 15 Number 2 GEORGETOWN ALUMNI CLUB ROSTER • Officers of local and regional Georgetown Alumni Clubs are listed here us a regulur fea ture of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Club Secreturies are requested to notify the Executive Secretary of the Alumni Association of any changes as soon as they occur. Los Angeles, Calif. Northeastern N. Y. Pres.: Edward S. Kuglen, Jr., FS '52, California Motor Express Pres.: Dr. Ernest Beaudoin, '54, 67 Chestnut St., Albany, N. Y. Co., 1751 South Santa Fe, Los Angeles, Calif. MAdison 7-8251 HO 3-4668 Secy.: Jay F. MacNulty, '58, 143 Pawling Ave., Troy, N. Y. Northern California Binghamton, N. Y. Lesser, '41, 54 Belden St., San Francisco 4, Pres.: Alvin M. St., Binghamton, 6-0292 Pres.: Jeremiah E. Ryan, '38, 107 Murray Calif. YUkon N. Y. 3-6161 Denver, Colo. Buffalo, N. Y. er, Col. Pres. : Charles P. Gallagher, '49, Central Bank, Denv Pres. : John F. Connell y, Jr., '52, 295 Voorhees Ave., Buffalo, N.Y. AC 2-0771 Secy.: John H. Napier, '47, 235 Cleveland Drive, Kenmore, Connecticut N. Y. BEdford 1646 Pres. : Bernard J. Dolan, '49, 207 Greenwood Ave., Beth el, Conn. Metropolitan N. Y. Delaware Pres.: George Harvey Cain, '42, Cerro de Pasco Corp., 300 Pres. : Joseph T. Walsh, '54, 2230 Pi ne St., Wilmington, Del. Park Avenue, New York 22,, N. Y. MUrray Hill 8-8822 Washington, D. C. Mid-Hudson Valley, N. Y. Pres. : James J. Bierbower, '47, 1625 K St., N.W. Washington 6, Pres. John J. Gartland, Jr., '35, 226 Union St., Poughkeepsie, D. -

Washington, Wednesday, December 7, 1955 TITLE 9—ANIMALS

VOLUME 20 NUMBER 237 Washington, Wednesday, December 7 , 1955 TITLE 9— ANIM ALS AND (vi) That part of the City of Peabody lying south of Farm Avenue, northwest of CONTENTS Lynnfield Street, and east of Farm Avenue; ANIMAL PRODUCTS Page that part of the City of Peabody lying south Agricultural Marketing Service Chapter I— Agricultural Research of State Route No, 128, north of Lynnfield Rules and regulations: Service, Department of Agriculture Street, west of Summit Street, and east of Limes grown in Florida; con Farm Avenue; that part of the City of Pea tainer regulation_____ '______ 8986 Subchapter C— Interstate Transportation of body lying north of Lowell Street, east of Oranges, navel, grown in Ari Animals and Poultry U. S. Route No. 1, and west of Prospect zona and designated part of [B. A. I. Order 383, Revised, Arndt. 67] Street; and that part of the City of Peabody lying north of Lowell Street and' west of California; limitation of han Part 76—H og C h o le r a , S w i n e P l a g u e , Birch Street. dling____________ _____________ 8985 and O ther C ommunicable S w i n e Potatoes, Irish, grown in certain 5. Subdivisions (ii), (v ), and (viii) of D iseases designated counties in Idaho subparagraph (4) of paragraph (c), re and Malheur County, Oregon; Subpart B — V e s ic u l a r E x a n t h e m a lating to Hampden County in Massachu limitation of shipments______ 8985 changes i n areas quarantined setts, are deleted. -

Crash Claims Life of 'Amazing Young Man' from Gainesville

Gainesville team wins ShowMe Games! SEE PAGE 2 Ozark COunTy 75¢ GAINESVILLE,Times Mo. www.ozArkcouNtytimes.coM wEdNESdAy, JuLy 31, 2019 Three perish in head-on collision on Highway 5 north Crash claims life of ‘amazing young man’ from Gainesville A search warrant executed July 22 at John Bass’s residence in Caulfield turned up 98 grams of pure crystal methamphetamine. Ozark County Sheriff’s deputies estimate the street price of the drug somewhere around $20,000. Search warrant yields meth with street value estimated at $20,000 A Caulfield man is in the Ozark County Jail for traf- ficking methamphetamine after officers found approxi- mately $20,000 worth of meth at his residence when a July 22 search warrant was executed there. Officers also reportedly found empty bags, metric scales and other paraphernalia commonly used in processing and sell- John Bass ing meth. John William Bass, 52, faces charges of traf- ficking drugs and receiving stolen property. He was arrested July 24, and a bond-reduction hearing was scheduled to be held Tuesday before Associate Judge Raymond Gross. Results of that court appearance were not available at press time. According to the probable cause statement in the case prepared by Ozark County Sheriff’s Deputy Cpl. Curtis Dobbs, officers executed a Rachel Klessig says her son Danial, shown here with newborn brother Reuben, search warrant on the Bass house at 1988 Gene born earlier this year, was always helpful and kind to his eight siblings. “I’ve found Bean Drive in Caulfield in connection with infor- all these pictures of him snuggling his baby siblings, every one of them as they mation that Howell County officers obtained dur- came along,” she said. -

LCOL Jesse A. Marcel Sr USAAF W5CYI in the U.S.A.A.F

LCOL Jesse A. Marcel Sr USAAF W5CYI in the U.S.A.A.F. This was based upon his *1907-1986* To Theodule (laborer oyster experience analyzing aerial photography. He was industry) and Adelaide Bergeron Marcel, of sent to Harrisburg, Pa for training as a combat Bayou Blue, Houma, Terrebonne Parish, La. The photograph interpreter/Intel Officer. Marcel children consisted of 4 brothers Jesse, Paul, Willey and Dennis Marcel - Sisters Our subject requested combat October of 1943 Laurentine, Lucy, Louise and Jennie. and was assigned to the 5th Bomber Group command in S.W. Pacific Theater New Guinea. It appears you are going to receive more material For two years Marcel served first as a Squadron than you probably want to know, but bear with us. Intel Officer then Group Intel Officer, First we view the location Blue Bayou, it strikes participating in several campaigns that resulted in me as a hit tune that was a national the retaking of the Philippine treasure written by Roy Orbison Islands. Marcel had a total of 468 and Joe Melson in the early 60s hours of combat time, was and later a national hit by Linda intelligence officer for bomb wing, Ronstadt in 1977. Many of our flew as a pilot, waist gunner and dear friends loved that song and bombardier at different times. Was our subject Jesse Marcel was born downed one time, the third mission there. I could easily retire off the out of Port Moresby, his chest pack residuals that song still brings. chute saved his life. His commander rewarded his Jesse was a grad of Terrebonne dedication and abilities with 5 air High School Huoma Louisiana.