Understanding the Complexities and Origins of Gun Violence in Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Estimating the Causal Effect of Gangs in Chicago†

Competition in the Black Market: Estimating the Causal Effect of Gangs in Chicago† Bravo Working Paper # 2021-004 Jesse Bruhn † Abstract: I study criminal street gangs using new data that describes the geospatial distribution of gang territory in Chicago and its evolution over a 15-year period. Using an event study design, I show that city blocks entered by gangs experience sharp increases in the number of reported batteries (6%), narcotics violations (18.5%), weapons violations (9.8%), incidents of prostitution (51.9%), and criminal trespassing (19.6%). I also find a sharp reduction in the number of reported robberies (-8%). The findings cannot be explained by pre-existing trends in crime, changes in police surveillance, crime displacement, exposure to public housing demolitions, reporting effects, or demographic trends. Taken together, the evidence suggests that gangs cause small increases in violence in highly localized areas as a result of conflict over illegal markets. I also find evidence that gangs cause reductions in median property values (-$8,436.9) and household income (-$1,866.8). Motivated by these findings, I explore the relationship between the industrial organization of the black market and the supply of criminal activity. I find that gangs that are more internally fractured or operate in more competitive environments tend to generate more crime. This finding is inconsistent with simple, market-based models of criminal behavior, suggesting an important role for behavioral factors and social interactions in the production of gang violence. Keywords: Competition, Crime, Gangs, Neighborhoods, Urban, Violence JEL classification: J46, K24, O17, R23, Z13 __________________________________ † Previously circulated under the title "The Geography of Gang Violence.” * Economics Department, Brown University. -

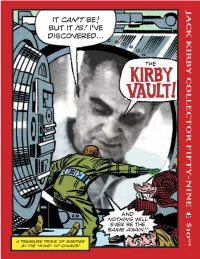

J a C K Kirb Y C Olle C T Or F If T Y- Nine $ 10

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-NINE $10 FIFTY-NINE COLLECTOR KIRBY JACK IT CAN’T BE! BUT IT IS! I’VE DISCOVERED... ...THE AND NOTHING WILL EVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!! 95 A TREASURE TROVE OF RARITIES BY THE “KING” OF COMICS! Contents THE OLD(?) The Kirby Vault! OPENING SHOT . .2 (is a boycott right for you?) KIRBY OBSCURA . .4 (Barry Forshaw’s alarmed) ISSUE #59, SUMMER 2012 C o l l e c t o r JACK F.A.Q.s . .7 (Mark Evanier on inkers and THE WONDER YEARS) AUTEUR THEORY OF COMICS . .11 (Arlen Schumer on who and what makes a comic book) KIRBY KINETICS . .27 (Norris Burroughs’ new column is anything but marginal) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .30 (the shape of shields to come) FOUNDATIONS . .32 (ever seen these Kirby covers?) INFLUENCEES . .38 (Don Glut shows us a possible devil in the details) INNERVIEW . .40 (Scott Fresina tells us what really went on in the Kirby household) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .42 (Adam McGovern & an occult fave) CUT-UPS . .45 (Steven Brower on Jack’s collages) GALLERY 1 . .49 (Kirby collages in FULL-COLOR) UNEARTHED . .54 (bootleg Kirby album covers) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .55 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) GALLERY 2 . .56 (unused DC artwork) TRIBUTE . .64 (the 2011 Kirby Tribute Panel) GALLERY 3 . .78 (a go-go girl from SOUL LOVE) UNEARTHED . .88 (Kirby’s Someday Funnies) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .90 PARTING SHOT . .100 Front cover inks: JOE SINNOTT Back cover inks: DON HECK Back cover colors: JACK KIRBY (an unused 1966 promotional piece, courtesy of Heritage Auctions) This issue would not have been If you’re viewing a Digital possible without the help of the JACK Edition of this publication, KIRBY MUSEUM & RESEARCH CENTER (www.kirbymuseum.org) and PLEASE READ THIS: www.whatifkirby.com—thanks! This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. -

COMICS Viva Il Re! L a Vita E Le Opere Del Co-Creatore Della Marvel

ADM Editore - nr. 35 settembre/ottobre 2017 Metti in collaborazione con Sui Fu FuMetti e Ale A StA Digit lA Rivi FUMETTO E SCUOLA l a parola a laura Scarpa e Paolo Forni SBAM!COMICS VIVA IL RE! l a vita e le opere del co-creatore della Marvel www.sbamcomics.it RE DEL TERRORE 100 ANNI DI JACK KIRBY ... IN CAMPO l otti e Mainardi ci raccontano Drawing by Ron Frenz, inks by Sal Buscema - Captain America © Marvel Comics America © Marvel - Captain Sal Buscema by inks Frenz, Ron by Drawing INTERVISTA ESCLUSIVA A il Diabolik “calcistico” FUMETTI RON FRENZ b ondi-leone-nanni L’ulTIMO DEI KIRBYANI! antonio Pannullo Fascinella-Zuppini NOVITÀ! arrivano in libreria gli IN QUESTO NUMERO 35 4 Pre-cover Dall’esperienza della rivista digitale fumettosa più bella di tutti i tempi, lo Sbam-sito ecco nelle migliori librerie i primi titoli della nostra nuovissima collana http://sbamcomics.it/ di volumi: sono nati gli Sbam! libri. Tutti i dettagli dell’iniziativa. 12 i n copertina SBAM!COMICS Il centenario del Re del Fumetto, Jack Kirby: per celebrarlo come si deve, abbiamo intervistato l’eccellente Ron Frenz, ultimo dei kirbyani e copertinista d’eccezione di questo numero di Sbam!, e ripercorso Sbam! Comics è la rivista digitale l’incredibile carriera del King! completamente gratuita per tutti 76 Fumetto e scuola Fortunatamente, sono ormai molto lontani i tempi in cui nelle scuole gli appassionati di fumetti: è diffusa la Sbam-vetrina dei nostri libri www.sbamcomics.it/sbamlibri vigeva il più assoluto ostracismo per i fumetti. Ma oggi, che rapporto c’è tra scuola e Nona Arte? Lo abbiamo chiesto a chi di insegnamento ogni due mesi tramite il sito del Fumetto se ne intende, laura Scarpa, e a un docente che propone www.sbamcomics.it. -

CRIME and VIOLENCE in CHICAGO a Geography of Segregation and Structural Disadvantage

CRIME AND VIOLENCE IN CHICAGO a Geography of Segregation and Structural Disadvantage Tim van den Bergh - Master Thesis Human Geography Radboud University, 2018 i Crime and Violence in Chicago: a Geography of Segregation and Structural Disadvantage Tim van den Bergh Student number: 4554817 Radboud University Nijmegen Master Thesis Human Geography Master Specialization: ‘Conflicts, Territories and Identities’ Supervisor: dr. O.T Kramsch Nijmegen, 2018 ii ABSTRACT Tim van den Bergh: Crime and Violence in Chicago: a Geography of Segregation and Structural Disadvantage Engaged with the socio-historical making of space, this thesis frames the contentious debate on violence in Chicago by illustrating how a set of urban processes have interacted to maintain a geography of racialized structural disadvantage. Within this geography, both favorable and unfavorable social conditions are unequally dispersed throughout the city, thereby impacting neighborhoods and communities differently. The theoretical underpinning of space as a social construct provides agency to particular institutions that are responsible for the ‘making’ of urban space in Chicago. With the use of a qualitative research approach, this thesis emphasizes the voices of people who can speak about the etiology of crime and violence from personal experience. Furthermore, this thesis provides a critique of social disorganization and broken windows theory, proposing that these popular criminologies have advanced a problematic normative production of space and impeded effective crime policy and community-police relations. Key words: space, disadvantage, race, crime & violence, Chicago (Under the direction of dr. Olivier Kramsch) iii Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 § 1.1 Studying crime and violence in Chicago .................................................................... 1 § 1.2 Research objective ................................................................................................... -

Examining Crime Hotspots in Chicago Using Bayesian Statistics

Examining Crime Hotspots in Chicago Using Bayesian Statistics Abstract Chicago currently leads the United States with the greatest number of homicides and violent crimes in recent years. Using police data from the City of Chicago’s Data Portal, we examined crime hot spots in Chicago and whether crime rates differ by geographic and demographic information. In general, we found that crime rate in Chicago has decreased between 2010 and 2015, though the rates differed between violent and non-violent crimes. Change in crime rate also varied geographically. We found that for areas with lower white populations, crime decreased as income rose. For areas with larger non-white populations, crime rate increased as income increased 1 1 Introduction Chicago currently leads the United States with the greatest number of homicides and violent crimes in recent years. In 2016, the number of homicides in Chicago increased 58% from the year before (Ford, 2017). Using police data from the City of Chicago’s Data Portal, we examined crime hot spots in Chicago and whether crime rates differ by geographic and demographic information. In this report, we defined hot spots as zipcodes with greater increases, or smaller decreases, in crime rates over time relative to other zipcodes in Chicago. In addition, we examined hot spots for both violent and non-violent crimes. Understanding crime hot spots can prove advantageous to law enforcement as they can better understand crime trends and create crime management strategies accordingly (Law, et al. 2014). A common approach to defining crime hot spots uses crime density. Thus, hot spots by this definition are areas with high crime rates that are also surrounded by other high-crime areas for one time period. -

The Impact of COVID-19 on Crime: a Spatial Temporal Analysis in Chicago

International Journal of Geo-Information Article The Impact of COVID-19 on Crime: A Spatial Temporal Analysis in Chicago Mengjie Yang 1 , Zhe Chen 1, Mengjie Zhou 1,2,* , Xiaojin Liang 3 and Ziyue Bai 1 1 College of Resources and Environmental Science, Hunan Normal University, Changsha 410081, China; [email protected] (M.Y.); [email protected] (Z.C.); [email protected] (Z.B.) 2 Key Laboratory of Geospatial Big Data Mining and Applications, Changsha 410081, China 3 School of Resources and Environmental Science, Wuhan University, 129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had tremendous and extensive impacts on the people’s daily activities. In Chicago, the numbers of crime fell considerably. This work aims to investigate the impacts that COVID-19 has had on the spatial and temporal patterns of crime in Chicago through spatial and temporal crime analyses approaches. The Seasonal-Trend decomposition procedure based on Loess (STL) was used to identify the temporal trends of different crimes, detect the outliers of crime events, and examine the periodic variations of crime distributions. The results showed a certain phase pattern in the trend components of assault, battery, fraud, and theft. The largest outlier occurred on 31 May 2020 in the remainder components of burglary, criminal damage, and robbery. The spatial point pattern test (SPPT) was used to detect the similarity between Citation: Yang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, the spatial distribution patterns of crime in 2020 and those in 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016, and to M.; Liang, X.; Bai, Z. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

TwoMorrows 2015 Catalog SAVE 15 ALL BOOKS, MAGS WHEN YOU% & DVDs ARE 15% OFF ORDER EVERY DAY AT ONLINE! www.twomorrows.com *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. Four Ways To Order: • Save us processing costs by ordering Print or Digital Editions ONLINE at www.twomorrows.com and you get at least 15% OFF cover price, plus exact weight-based postage (the more you order, the more you save on shipping—especially overseas customers)! Plus you’ll get a FREE PDF DIGITAL EDITION of each PRINT item you order, where available. OR: • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL DIGITALEDITIONS and add $1 per magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US for Media Mail shipping. AVAILABLE OUTSIDE THE US, PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! OR: • Download our new Apps on the Apple and Android App Stores! OR: • Use the Diamond Order Code to order at your local comic book shop! CONTENTS DIGITAL ONLY BOOKS . 2 AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES . .3 MODERN MASTERS SERIES . 4-5 COMPANION BOOKS . 6-7 ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES . 8-9 COMICS & POP CULTURE BOOKS . 10 ROUGH STUFF & WRITE NOW . 11 DRAW! MAGAZINE . 12 HOW-TO BOOKS . 13 COMIC BOOK CREATOR MAGAZINE . 14 COMIC BOOK ARTIST MAGAZINE . 15 JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR . 16-19 ALTER EGO MAGAZINE . 20-27 BACK ISSUE! MAGAZINE . 28-32 To be notified of exclusive sales, limited editions, and new releases, sign up for our mailing list! All characters TM & ©2015 their respective owners. -

GUN VIOLENCE in CHICAGO, 2016 GUN VIOLENCE in CHICAGO, 2016 January 2017 University of Chicago Crime Lab1

GUN VIOLENCE IN CHICAGO, 2016 GUN VIOLENCE IN CHICAGO, 2016 January 2017 University of Chicago Crime Lab1 Acknowledgments: The University of Chicago Crime Lab is a privately-funded, independent, non-partisan academic research center founded in 2008 to help cities identify the most effective and humane ways to control crime and violence, and reduce the harms associated with the administration of criminal justice. We are grateful to the Chicago Police Department for making available the data upon which this report is based, to Ben Hansen for help assembling data on Chicago weather patterns, and to Aaron Chalfin, Philip Cook, Aurélie Ouss, Harold Pollack, and Shari Runner for valuable comments. We thank the Joyce Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the McCormick Foundation, and the Pritzker Foundation for support of the University of Chicago Crime Lab and Urban Labs, as well as Susan and Tom Dunn, and Ira Handler. All opinions and any errors are our own and do not necessarily reflect those of our funders or of any government agencies. 1 This report was produced by Max Kapustin, Jens Ludwig, Marc Punkay, Kimberley Smith, Lauren Speigel, and David Welgus, with the invaluable assistance of Roseanna Ander, Nathan Hess, and Julia Quinn. Please direct any comments and questions to [email protected]. 2 INTRODUCTION A total of 764 people were murdered in Chicago in 2016. They were sons, brothers, and fathers; sisters, daughters, and mothers; they were, as the title of The New York Times reporter Fox Butterfield’s book on urban violence noted,All God’s Children. -

Street Code Adherence, Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Capacity of Violent Offending Versus Non-Offending Urban Youth to Mentalize About Disrespect Murder

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Street Code Adherence, Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Capacity of Violent Offending versus Non-Offending Urban Youth to Mentalize About Disrespect Murder Zoe A. Berko Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/523 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Street Code Adherence, Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Capacity of Violent Offending versus Non-Offending Urban Youth to Mentalize About Disrespect Murder by Zoë A. Berko A dissertation proposal submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 Zoë A. Berko All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________ ________________________ Date Steven Tuber, Ph.D. Chair of Examining Committee __________________ ________________________ Date Joshua Brumberg, Ph.D. Executive Officer in Psychology Arietta Slade, Ph.D. L. Thomas Kucharski, Ph.D. Elliot L. Jurist, Ph.D., Ph.D. Diana Puñales-Morejon, Ph.D. Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract STREET CODE ADHERENCE, CALLOUS-UNEMOTIONAL TRAITS AND THE CAPACITY OF VIOLENT OFFENDING VERSUS NON-OFFENDING URBAN YOUTH TO MENTALIZE ABOUT DISRESPECT MURDER By Zoë A. -

Project Safe Neighborhoods in Chicago: Looking Back a Decade Later Ben Grunwald

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 107 | Issue 1 Article 3 Winter 2017 Project Safe Neighborhoods in Chicago: Looking Back a Decade Later Ben Grunwald Andrew V. Papachristos Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Recommended Citation Ben Grunwald and Andrew V. Papachristos, Project Safe Neighborhoods in Chicago: Looking Back a Decade Later, 107 J. Crim. L. & Criminology (2017). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol107/iss1/3 This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 3. GRUNWALD 4/6/2017 6:45 PM 0091-4169/17/10701-0131 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 107, No. 1 Copyright © 2017 by Ben Grunwald and Andrew V. Papachristos Printed in U.S.A. CRIMINOLOGY PROJECT SAFE NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHICAGO: LOOKING BACK A DECADE LATER BEN GRUNWALD* & ANDREW V. PAPACHRISTOS** Project Safe Neighborhoods (PSN) is a federally funded initiative that brings together federal, state, and local law enforcement to reduce gun violence in urban centers. In Chicago, PSN implemented supply-side gun policing tactics, enhanced federal prosecution of gun crimes, and notification forums warning offenders of PSN’s heightened criminal sanctions. Prior evaluations provide evidence that PSN initiatives have reduced crime in the first few years of their operation. But over a decade after the program was established, we still know little about whether these effects are sustained over an extended period of time. -

Barry Latzer on Robert Nixon and Police Torture in Chicago

Elizabeth Dale. Robert Nixon and Police Torture in Chicago, 1871-1972. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2016. 184 pp. $32.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-87580-739-3. Reviewed by Barry Latzer Published on H-Law (September, 2016) Commissioned by Michael J. Pfeifer (John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York) The aim of Elizabeth Dale’s short and com‐ Probably not. Or that the Chicago Police Depart‐ pelling book is to show that the long list of abuses ment has a culture of “torturing” suspects, which of suspects by Chicago police detective Jon Burge, is why Burge cannot be explained merely by which took place between 1972 and 1991, were lapsed supervision (p. 2)? Perhaps. not anomalies. Burge, it will be recalled, ended up Another unresolved issue involves the word in prison and the City of Chicago apologized for “torture,” used matter-of-factly throughout the his abuses, paying out $100,000 in damages to his book. Unlike Dale, I don’t think torture is a self-ex‐ victims, expected to number between ffty and planatory term, though it certainly is an inflam‐ eighty-eight people. Dale intends to prove that it matory one. The United Nations Convention did not start with Burge, that he was just the most Against Torture, which Dale does not reference recent and notorious illustration of a systematic until p. 114 of her book, states that the term effort by Chicago police to “torture” suspects means “any act by which severe pain or suffering, stretching back to the nineteenth century. Her whether physical or mental, is intentionally in‐ goal, she says, is to recapture the history of these flicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining abuses.