Street Codes, Routine Activities, Neighborhood Context, and Victimization: an Examination of Alternative Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

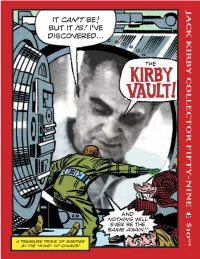

J a C K Kirb Y C Olle C T Or F If T Y- Nine $ 10

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-NINE $10 FIFTY-NINE COLLECTOR KIRBY JACK IT CAN’T BE! BUT IT IS! I’VE DISCOVERED... ...THE AND NOTHING WILL EVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!! 95 A TREASURE TROVE OF RARITIES BY THE “KING” OF COMICS! Contents THE OLD(?) The Kirby Vault! OPENING SHOT . .2 (is a boycott right for you?) KIRBY OBSCURA . .4 (Barry Forshaw’s alarmed) ISSUE #59, SUMMER 2012 C o l l e c t o r JACK F.A.Q.s . .7 (Mark Evanier on inkers and THE WONDER YEARS) AUTEUR THEORY OF COMICS . .11 (Arlen Schumer on who and what makes a comic book) KIRBY KINETICS . .27 (Norris Burroughs’ new column is anything but marginal) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .30 (the shape of shields to come) FOUNDATIONS . .32 (ever seen these Kirby covers?) INFLUENCEES . .38 (Don Glut shows us a possible devil in the details) INNERVIEW . .40 (Scott Fresina tells us what really went on in the Kirby household) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .42 (Adam McGovern & an occult fave) CUT-UPS . .45 (Steven Brower on Jack’s collages) GALLERY 1 . .49 (Kirby collages in FULL-COLOR) UNEARTHED . .54 (bootleg Kirby album covers) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .55 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) GALLERY 2 . .56 (unused DC artwork) TRIBUTE . .64 (the 2011 Kirby Tribute Panel) GALLERY 3 . .78 (a go-go girl from SOUL LOVE) UNEARTHED . .88 (Kirby’s Someday Funnies) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .90 PARTING SHOT . .100 Front cover inks: JOE SINNOTT Back cover inks: DON HECK Back cover colors: JACK KIRBY (an unused 1966 promotional piece, courtesy of Heritage Auctions) This issue would not have been If you’re viewing a Digital possible without the help of the JACK Edition of this publication, KIRBY MUSEUM & RESEARCH CENTER (www.kirbymuseum.org) and PLEASE READ THIS: www.whatifkirby.com—thanks! This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. -

COMICS Viva Il Re! L a Vita E Le Opere Del Co-Creatore Della Marvel

ADM Editore - nr. 35 settembre/ottobre 2017 Metti in collaborazione con Sui Fu FuMetti e Ale A StA Digit lA Rivi FUMETTO E SCUOLA l a parola a laura Scarpa e Paolo Forni SBAM!COMICS VIVA IL RE! l a vita e le opere del co-creatore della Marvel www.sbamcomics.it RE DEL TERRORE 100 ANNI DI JACK KIRBY ... IN CAMPO l otti e Mainardi ci raccontano Drawing by Ron Frenz, inks by Sal Buscema - Captain America © Marvel Comics America © Marvel - Captain Sal Buscema by inks Frenz, Ron by Drawing INTERVISTA ESCLUSIVA A il Diabolik “calcistico” FUMETTI RON FRENZ b ondi-leone-nanni L’ulTIMO DEI KIRBYANI! antonio Pannullo Fascinella-Zuppini NOVITÀ! arrivano in libreria gli IN QUESTO NUMERO 35 4 Pre-cover Dall’esperienza della rivista digitale fumettosa più bella di tutti i tempi, lo Sbam-sito ecco nelle migliori librerie i primi titoli della nostra nuovissima collana http://sbamcomics.it/ di volumi: sono nati gli Sbam! libri. Tutti i dettagli dell’iniziativa. 12 i n copertina SBAM!COMICS Il centenario del Re del Fumetto, Jack Kirby: per celebrarlo come si deve, abbiamo intervistato l’eccellente Ron Frenz, ultimo dei kirbyani e copertinista d’eccezione di questo numero di Sbam!, e ripercorso Sbam! Comics è la rivista digitale l’incredibile carriera del King! completamente gratuita per tutti 76 Fumetto e scuola Fortunatamente, sono ormai molto lontani i tempi in cui nelle scuole gli appassionati di fumetti: è diffusa la Sbam-vetrina dei nostri libri www.sbamcomics.it/sbamlibri vigeva il più assoluto ostracismo per i fumetti. Ma oggi, che rapporto c’è tra scuola e Nona Arte? Lo abbiamo chiesto a chi di insegnamento ogni due mesi tramite il sito del Fumetto se ne intende, laura Scarpa, e a un docente che propone www.sbamcomics.it. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

TwoMorrows 2015 Catalog SAVE 15 ALL BOOKS, MAGS WHEN YOU% & DVDs ARE 15% OFF ORDER EVERY DAY AT ONLINE! www.twomorrows.com *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. Four Ways To Order: • Save us processing costs by ordering Print or Digital Editions ONLINE at www.twomorrows.com and you get at least 15% OFF cover price, plus exact weight-based postage (the more you order, the more you save on shipping—especially overseas customers)! Plus you’ll get a FREE PDF DIGITAL EDITION of each PRINT item you order, where available. OR: • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL DIGITALEDITIONS and add $1 per magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US for Media Mail shipping. AVAILABLE OUTSIDE THE US, PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! OR: • Download our new Apps on the Apple and Android App Stores! OR: • Use the Diamond Order Code to order at your local comic book shop! CONTENTS DIGITAL ONLY BOOKS . 2 AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES . .3 MODERN MASTERS SERIES . 4-5 COMPANION BOOKS . 6-7 ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES . 8-9 COMICS & POP CULTURE BOOKS . 10 ROUGH STUFF & WRITE NOW . 11 DRAW! MAGAZINE . 12 HOW-TO BOOKS . 13 COMIC BOOK CREATOR MAGAZINE . 14 COMIC BOOK ARTIST MAGAZINE . 15 JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR . 16-19 ALTER EGO MAGAZINE . 20-27 BACK ISSUE! MAGAZINE . 28-32 To be notified of exclusive sales, limited editions, and new releases, sign up for our mailing list! All characters TM & ©2015 their respective owners. -

Street Code Adherence, Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Capacity of Violent Offending Versus Non-Offending Urban Youth to Mentalize About Disrespect Murder

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Street Code Adherence, Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Capacity of Violent Offending versus Non-Offending Urban Youth to Mentalize About Disrespect Murder Zoe A. Berko Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/523 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Street Code Adherence, Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Capacity of Violent Offending versus Non-Offending Urban Youth to Mentalize About Disrespect Murder by Zoë A. Berko A dissertation proposal submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 Zoë A. Berko All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Clinical Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________ ________________________ Date Steven Tuber, Ph.D. Chair of Examining Committee __________________ ________________________ Date Joshua Brumberg, Ph.D. Executive Officer in Psychology Arietta Slade, Ph.D. L. Thomas Kucharski, Ph.D. Elliot L. Jurist, Ph.D., Ph.D. Diana Puñales-Morejon, Ph.D. Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract STREET CODE ADHERENCE, CALLOUS-UNEMOTIONAL TRAITS AND THE CAPACITY OF VIOLENT OFFENDING VERSUS NON-OFFENDING URBAN YOUTH TO MENTALIZE ABOUT DISRESPECT MURDER By Zoë A. -

May 5, 2007 (Pages 2083-2168)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 37 (2007) Repository 5-5-2007 May 5, 2007 (Pages 2083-2168) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2007 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "May 5, 2007 (Pages 2083-2168)" (2007). Volume 37 (2007). 18. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2007/18 This May is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 37 (2007) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 37 Number 18 Saturday, May 5, 2007 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 2083—2168 Agencies in this issue The Courts Bureau of Professional and Occupational Affairs Department of Agriculture Department of Banking Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Public Welfare Department of Transportation Fish and Boat Commission Insurance Department Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission State Board of Nursing State Board of Vehicle Manufacturers, Dealers and Salespersons Detailed list of contents appears inside. PRINTED ON 100% RECYCLED PAPER Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): No. 390, May 2007 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA BULLETIN Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- reau, 647 Main Capitol Building, State & Third Streets, (ISSN 0162-2137) Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publication and effectiveness of Com- monwealth Documents). -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

The JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #63 All characters TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. $10.95 SUMMER 2014 THE ISSUE #63, SUMMER 2014 C o l l e c t o r Contents The Marvel Universe! OPENING SHOT . .2 (let’s put the Stan/Jack issue to rest in #66, shall we?) A UNIVERSE A’BORNING . .3 (the late Mark Alexander gives us an aerial view of Kirby’s Marvel Universe) GALLERY . .37 (mega Marvel Universe pencils) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .48 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) JACK F.A.Q.s . .49 (in lieu of Mark Evanier’s regular column, here’s his 2008 Big Apple Kirby Panel, with Roy Thomas, Joe Sinnott, and Stan Goldberg) KIRBY OBSCURA . .64 (the horror! the horror! of S&K) KIRBY KINETICS . .67 (Norris Burroughs on Thing Kong) IF WHAT? . .70 (Shane Foley ponders how Jack’s bad guys could’ve been badder) RETROSPECTIVE . .74 (a look at key moments in Kirby’s later life and career) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .82 (we go “under the sea” with Triton) CUT ’N’ PASTE . .84 (the lost FF #110 collage) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .86 (the return of the return of Captain Victory) UNEARTHED . .89 (the last survivor of Kirby’s Marvel Universe?) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .91 PARTING SHOT . .96 Cover inks: MIKE ROYER Cover color: TOM ZIUKO If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, PLEASE READ THIS: This is copyrighted material, NOT intended Spider-Man is the one major Marvel character we don’t cover this issue, but here’s a great sketch of Spidey that Jack drew for for downloading anywhere except our website or Apps. -

Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish- American Experience Brian Klotz University of Rhode Island, [email protected]

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2009 Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish- American Experience Brian Klotz University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Klotz, Brian, "Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish-American Experience" (2009). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 127. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/127http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Klotz 1 Brian Klotz HPR401 Spring 2009 Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish-American Experience In 1934, the comic book was born. Its father was one Maxwell Charles Gaines (né Ginsberg), a down-on-his-luck businessman whose previous career accomplishments included producing “painted neckties emblazoned with the anti-Prohibition proclamation ‘We Want Beer’” (Kaplan 2). Such things did not provide a sufficient income, and so a desperate Gaines moved himself and his family back in to his mother’s house in the Bronx. It was here, in a dusty attic, that Gaines came across some old newspaper comic strips and had his epiphany. Working with Eastern Color Printing, a “company that printed many of the Sunday newspaper comics sections in the Northeast” (Kaplan 2-3), Gaines began publishing pamphlet-sized collections of old comic strips to be sold to the public (this concept had been toyed with previously, but only as premiums or giveaways, not as an actual retail product). -

100 Top Creators Celebrate Jack Kirby's Greatest Work 100 Top Creators Celebrate Jack Kirby's Greatest Work 100 Top Creators

100100100 TopTopTop CreatorsCreatorsCreators CelebrateCelebrate JackJackJack Kirby’sKirby’sKirby’s GreatestGreatest WorkWork TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by John Morrow..... 6 27. Kyle Baker: 54. José Villarrubia: 80. Kevin Eastman: Captain America.................... 60 Captain America #109......... 112 Kamandi #16 ....................... 162 THE GOLDEN AGE 28. Shannon Wheeler: 55. Joe Sinnott: 81. Thomas Yeates: 1. Paris Cullins: Blue Beetle....... 8 The X-Men #8........................ 62 Fantastic Four #95 ............... 114 Kamandi #19 ....................... 164 2. Allen Bellman: 29. Larry Hama: Sgt. Fury #13... 64 82. Scott Shaw!: Captain America Comics #5 .... 10 DC AND THE FOURTH WORLD 30. Steve Mitchell: 1st Issue Special #6 ............. 166 56. Jerry Ordway: 3. Mike Vosburg: Sgt. Fury #13 ......................... 65 83. Alan Davis: OMAC #4 ....... 170 Stuntman #2 ............................ 12 Mister Miracle #1 ............... 116 31. Fred Hembeck: 84. Batton Lash: 57. Dustin Nguyen: THE 1950s Fantastic Four #34 ................. 66 Our Fighting Forces ............. 172 The Forever People #6......... 117 4. John Workman: 32. W alter Simonson: 85. Alex Ross: 58. Will Meugniot: Boys’ Ranch #3 ........................ 14 Journey Into Mystery #113 ... 68 The Sandman #4 ................. 174 Mattel Comic Game Cards ...118 5. Bill Black: Captain 3-D #1 .... 16 33. Adam Hughes: 59. Al Milgrom: Jimmy Olsen RETURN TO MARVEL 6. T revor Von Eeden: Tales of Suspense #66 .......... 70 Adventures .......................... 120 86. Evan Dorkin: Fighting American #1 .............. 18 34. P . Craig Russell: 60. Cliff Galbraith: Superman’s Captain America’s Fantastic Four #40–70........... 72 7. Bob Burden: Pal, Jimmy Olsen #134........ 123 Bicentennial Battles ............ 176 Fighting American ................... 20 35. Richard Howell: 61. Dan Jurgens: Superman’s 87. Bruce Timm: Fantastic Four #45 ................ -

Understanding the Complexities and Origins of Gun Violence in Chicago

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2021 Understanding the Complexities and Origins of Gun Violence in Chicago Christopher Bilicic [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the American Politics Commons, Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social Justice Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Bilicic, Christopher, "Understanding the Complexities and Origins of Gun Violence in Chicago". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2021. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/866 UNDERSTANDING THE COMPLEXITIES AND ORIGINS OF GUN VIOLENCE IN CHICAGO A thesis presented by Christopher Bilicic to The Political Science Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Political Science Trinity College Hartford, CT April 10, 2021 Professor Anna Terwiel Stefanie Chambers Thesis Advisor Department Chair 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Chicago’s History of Housing Discrimination and Racial Segregation 28 Chapter 3: Legal Cynicism and Chicago’s History of Police Abuse 68 Chapter 4: Public Policy Solutions 83 Chapter 5: Conclusion 134 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 4 Last summer, in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side, Yasmin Miller was driving home from her local laundromat with her 20-month-old son, Sincere Gaston, seated in the back of her car. Several stray bullets from a nearby shooting hit Yasmin’s car, killing her son. At a vigil for Sincere, Yasmin Miller made an emotional plea to her South Side community: “We need your help. -

Jack Kirby Collector #77•Summer 2019•$10.95

THE BREAK OUT DDT AND RUN FOR YOUR LIFE! IT’S THE AND BUGS ISSUE JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #77•SUMMER 2019•$10.95 with ERIC POWELL•MICHAEL CHO•MARK EVANIER•SEAN KLEEFELD•BARRY FORSHAW•ADAM McGOVERN•NORRIS BURROUGHS•SHANE FOLEY•JERRY BOYD 4 5 6 3 0 0 8 5 6 2 8 1 STARRING JACK KIRBY•DIRECTED BY JOHN MORROW•FEATURING RARE KIRBY ARTWORK•A TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING RELEASE Monster, Forager TM & © DC ComicsNew • Goom Gods TM TM & ©& Marvel © DC Characters,Comics. Inc. • Lightning Lady TM & © Jack Kirby Estate Contents THE Monsters & Bugs! OPENING SHOT ................2 ( something’s bugging the editor) FOUNDATIONS ................4 (S&K show the monsters inside us) ISSUE #77, SUMMER 2019 RETROSPECTIVE ..............12 Collector (from Vandoom to Von Doom) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY .....23 (you recall Giganto, don’t you?) KIRBY KINETICS ..............25 (the FF’s strange evolution) INFLUENCEES ................30 (cover inker Eric Powell speaks) GALLERY 1 ..................34 (monsters, in pencil) HORRORFLIK ................42 (Jack’s ill-fated Empire Pictures deal) KIRBY OBSCURA .............46 (vintage 1950s monster stories) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM .........48 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) POW!ER ....................49 (two monster Kirby techniques) UNEXPLAINED ...............51 (three major myths of Kirby’s) BOYDISMS ...................54 (monsters, all the way back to the ’40s) KIRBY AS A GENRE ...........64 (Michael Cho on his Kirby influences) ANTI-MAN ..................68 (we go foraging for bugs) GALLERY 2 ..................72 (the bugs attack!) UNDISCOVERED -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-EIGHT $9 95 IN THE US Jack Kirby (right) Burne Hogarth’s classic Dynamic Figure Drawing was a revelation to me as a budding teenage artist, but deep down I always wondered what a “how-to” book by Kirby would be like. Jack DYNAMIC never produced such a book, and if he had, it’s a safe bet nobody would’ve bought it for the words anyway. So here’s my take on what the cover might’ve FIGURE looked like. Hulk, Thing TM & ©2003 Marvel Characters, Inc. Big Barda TM & ©2003 DC Comics. DRAWING COPYRIGHTS: Atlas, Big Barda, Boy Commandos, Challengers of the Unknown, Darkseid, Demon, Dingbats of Danger Street, Dr. Fate, Forager, Forever People, Green Lantern, Jimmy Olsen, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Mr. Miracle, Negative Man, New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Promethea, Pyra, Spectre, Superman, Toxl the World Killer, Wonder Woman, Young Romance TM & ©2003 DC Comics • Black Bolt, Black Panther, Bucky, Capt. America, Crystal, Dr. Doom, Dr. Strange, Dragon Man, Enchantress, Fantastic Four, Galactus, Gorgon, Hercules, Hulk, Human Torch, Infant Terrible, Inhumans, Invisible Girl, Iron Man, Karnak, Liberty Legion, Magneto, Makarri, Medusa, Melter, Modok, Mr. Fantastic, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Red Skull, Sgt. Fury, Silver Surfer, Spider-Man, Sub-Mariner, Super Skrull, Thing, Thor, Triton, Two-Gun Kid, Warlock TM & ©2003 Marvel Characters, Inc. • Enchantra, Silver Star, The Family, Capt. Glory, Capt. Victory, Satan's Six, Inky, Galaxy Green TM & Spotlighting the artist of ©2003 Jack Kirby Estate • Boys' Ranch, Police Trap TM & ©2003 Simon & Kirby • THE FOURTH WORLD TRILOGY Thundarr TM & ©2003 Ruby-Spears Productions, Inc.