Making Peace-Keeping Peace a Study on Community Con Ict Management in Puttalam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 3 8 147 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 21.7 MILLION (US$32 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A PUTTALAM HOUSING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized JANUARY 24,2007 Sustainable Development South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 13,2006) Currency Unit = Sri Lankan Rupee 108 Rupees (Rs.) = US$1 US$1.50609 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LTF Land Task Force AG Auditor General LTTE Liberation Tigers ofTamil Eelam CAS Country Assistance Strategy NCB National Competitive Bidding CEB Ceylon Electricity Board NGO Non Governmental Organization CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment NEIAP North East Irrigated Agriculture Project CQS Selection Cased on Consultants Qualifications NEHRP North East Housing Reconstruction Program CSIA Continuous Social Impact Assessment NPA National Procurement Agency CSP Camp Social Profile NPV Not Present Value CWSSP Community Water Supply and Sanitation NWPEA North Western Provincial Environmental Act Project DMC District Monitoring Committees NWPRD NorthWest Provincial Roads Department -

Balasooriya Hospital Pvt Ltd 1

“We are proudly abstracting here our journey in medical industry with the gathered pride of excellency…” COMPANY PROFILE BALASOORIYA HOSPITAL PVT LTD 118A, KURUNEGALA ROAD, PUTTALAM. HOT LINE: 032 2266299/ 032 2267153/ 071 4019149 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.balasooriyahospital.com Chairman’s Review Page 1 of 34 Table of Content Contents… Subject Pg. no Vision & Mission 02 Company Overview 03- 04 Our Achievements 05- 06 Our Specialities 07- 09 Our services 1. 24 hrs Laboratory Service 10- 14 2. 24 hrs Pharmacy 15 3. Admissions 16- 18 4. 24 hrs OPD 19 5. Specialists Consultation 20 6. 24 hrs X-Ray 21 7. ECG 21 8. EEG 22 9. Ultra Sound Scanning 22 10. Dental 23 11. Optical Unit 24 12. 24 hrs Ambulance Service 24 13. Physiotherapy 25 14. Spirometry & Lung Function Test 25 15. Cardiac Echo (Pediatric/ Adult) 26 16. Audiometry+ PTA 26 17. Mobile Medical Service 27 18. Home Visits & Nursing Services 27 Branches 28 List of Clients 29 Contact Details 30 Page 2 of 34 vision & Mission Page 3 of 34 Company Overview THE COMMENCENMENT The chief of Balasooriya Hospital (Pvt) Ltd, Mr. B.M.A.P.G. Balasooriya, aforetime was a Medical Laboratory Technologist by profession and on the necessity of the service he got a transfer to Base Hospital, Puttalam on 17th of September, 1998. He identified the requirement of an effective and efficient medical service to Puttalam area and has paid his attention on initiating a Medical Laboratory in a rented small shop committing his hours after duty and government holidays. -

Water Balance Variability Across Sri Lanka for Assessing Agricultural and Environmental Water Use W.G.M

Agricultural Water Management 58 (2003) 171±192 Water balance variability across Sri Lanka for assessing agricultural and environmental water use W.G.M. Bastiaanssena,*, L. Chandrapalab aInternational Water Management Institute (IWMI), P.O. Box 2075, Colombo, Sri Lanka bDepartment of Meteorology, 383 Bauddaloka Mawatha, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka Abstract This paper describes a new procedure for hydrological data collection and assessment of agricultural and environmental water use using public domain satellite data. The variability of the annual water balance for Sri Lanka is estimated using observed rainfall and remotely sensed actual evaporation rates at a 1 km grid resolution. The Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL) has been used to assess the actual evaporation and storage changes in the root zone on a 10- day basis. The water balance was closed with a runoff component and a remainder term. Evaporation and runoff estimates were veri®ed against ground measurements using scintillometry and gauge readings respectively. The annual water balance for each of the 103 river basins of Sri Lanka is presented. The remainder term appeared to be less than 10% of the rainfall, which implies that the water balance is suf®ciently understood for policy and decision making. Access to water balance data is necessary as input into water accounting procedures, which simply describe the water status in hydrological systems (e.g. nation wide, river basin, irrigation scheme). The results show that the irrigation sector uses not more than 7% of the net water in¯ow. The total agricultural water use and the environmental systems usage is 15 and 51%, respectively of the net water in¯ow. -

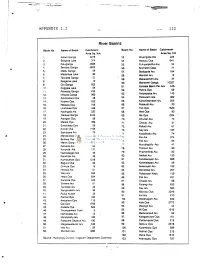

River Basins

APPENDIX I.I 122 River Basins Basin No Name of Basin Catchment Basin No. Name of Basin Catchment Area Sq. Km. Area Sq. Km 1. Kelani Ganga 2278 53. Miyangolla Ela 225 2. Bolgoda Lake 374 54. Maduru Oya 1541 3. Kaluganga 2688 55. Pulliyanpotha Aru 52 4. Bemota Ganga 6622 56. Kirimechi Odai 77 5. Madu Ganga 59 57. Bodigoda Aru 164 6. Madampe Lake 90 58. Mandan Aru 13 7. Telwatte Ganga 51 59. Makarachchi Aru 37 8. Ratgama Lake 10 60. Mahaweli Ganga 10327 9. Gin Ganga 922 61. Kantalai Basin Per Ara 445- 10. Koggala Lake 64 62. Panna Oya 69 11. Polwatta Ganga 233 12. Nilwala Ganga 960 63. Palampotta Aru 143 13. Sinimodara Oya 38 64. Pankulam Ara 382 14. Kirama Oya 223 65. Kanchikamban Aru 205 15. Rekawa Oya 755 66. Palakutti A/u 20 16. Uruhokke Oya 348 67. Yan Oya 1520 17. Kachigala Ara 220 68. Mee Oya 90 18. Walawe Ganga 2442 69. Ma Oya 1024 19. Karagan Oya 58 70. Churian A/u 74 20. Malala Oya 399 71. Chavar Aru 31 21. Embilikala Oya 59 72. Palladi Aru 61 22. Kirindi Oya 1165 73. Nay Ara 187 23. Bambawe Ara 79 74. Kodalikallu Aru 74 24. Mahasilawa Oya 13 75. Per Ara 374 25. Butawa Oya 38 76. Pali Aru 84 26. Menik Ganga 1272 27. Katupila Aru 86 77. Muruthapilly Aru 41 28. Kuranda Ara 131 78. Thoravi! Aru 90 29. Namadagas Ara 46 79. Piramenthal Aru 82 30. Karambe Ara 46 80. Nethali Aru 120 31. -

GEOGRAPHY Grade 11 (For Grade 11, Commencing from 2008)

GEOGRAPHY Grade 11 (for Grade 11, commencing from 2008) Teachers' Instructional Manual Department of Social Sciences Faculty of Languages, Humanities and Social Sciences National Institute of Education Maharagama. 2008 i Geography Grade 11 Teachers’ Instructional Manual © National Institute of Education First Print in 2007 Faculty of Languages, Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Social Science National Institute of Education Printing: The Press, National Institute of Education, Maharagama. ii Forward Being the first revision of the Curriculum for the new millenium, this could be regarded as an approach to overcome a few problems in the school system existing at present. This curriculum is planned with the aim of avoiding individual and social weaknesses as well as in the way of thinking that the present day youth are confronted. When considering the system of education in Asia, Sri Lanka was in the forefront in the field of education a few years back. But at present the countries in Asia have advanced over Sri Lanka. Taking decisions based on the existing system and presenting the same repeatedly without a new vision is one reason for this backwardness. The officers of the National Institute of Education have taken courage to revise the curriculum with a new vision to overcome this situation. The objectives of the New Curriculum have been designed to enable the pupil population to develop their competencies by way of new knowledge through exploration based on their existing knowledge. A perfectly new vision in the teachers’ role is essential for this task. In place of the existing teacher-centred method, a pupil-centred method based on activities and competencies is expected from this new educa- tional process in which teachers should be prepared to face challenges. -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind. -

Dry Zone Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project

Supplementary Appendix L/Puttalam Government of Sri Lanka Asian Development Bank Technical Assistance Project Number: 4853-SRI Sri Lanka: Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project (DZUWSP) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION: PUTTALAM (DRAFT) MARCH 2008 Supplementary Appendix L/Puttalam i CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 1 A. Purpose of the report ............................................................................................................................ 1 B. Extent of IEE study ............................................................................................................................... 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT......................................................................... 4 A. Type, Category and Need..................................................................................................................... 4 B. Location, Size and Implementation Schedule....................................................................................... 5 C. Description of the Sub-projects............................................................................................................. 5 III. DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT ............................................................. 12 A. Physical Resources ............................................................................................................................ 12 B. Ecological Resources ........................................................................................................................ -

Ground Water in the Coconut Triangle

31 COCOS, (1983) 1, 31-34 Printed in Sri Lanka Ground water in the coconut triangle A. DENIS N. FERNANDO Ministry of Mahaweli Development, Colombo INTRODUCTION The major part of Sri Lanka's coconut production comes from the Coconut Triangle, which is the area between Puttalam, Kurunegala and Colombo. More than half the coconut lands in the Coconut Triangle are in the dry and inter mediate climatic rones, where the productivity is relatively low due to insufficient rainfall. It was therefore conceivable that the provision of irrigation facilities, sufficient to over come the rainfall deficit and meet the water requirement of the coconut palms, would lead to a substantial increase in coconut production. In addition the intercropping of the coconut lands would be feasible if there is suffi cient ground water for these crops as well. It was against this background that this study of the ground water potential was initiated. In 1973 the author prepared a reconnaisance level map of ground water potential in Sri Lanka. (Anonymous, 1973) This was a first approximation, as it was based on hydrogeological boundaries at a lower scale of mapping. In 1981 a semi-detailed Hydrogeology map was prepared by the author with more sub - divisions of the hydrogeological categories. Based on this map which was of greater accuracy and on a larger scale, a second approximation of the ground water potential was determined. HYDROGEOLOGY The accompanying Hydrogeology map of the Coconut Triangle (Fig. 1), which includes parts of the districts of Puttalam, Kuruneg3la and Gampaha, has been divided into the following major categories, viz.; 1. -

Puttalam Lagoon System an Environmental and Fisheries Profile

REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) --------------------------------------------------------- An Environmental and Fisheries Profile of the Puttalam Lagoon System (Activity 1.4.1 : Consolidate and finalize reports on physio-chemical, geo-morphological, socio-economic, fisheries, environmental and land use associated with the Puttalam lagoon ecosystem) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Sriyanie Miththapala (compiler) IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Sri Lanka Country Office October 2011 REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) – SRI LANKA An Environmental and Fisheries Profile of the Puttalam Lagoon System (Activity 1.4.1- Consolidate and finalize reports on physio-chemical, geo-morphological, socio-economic, fisheries, environment and land use associated with Puttalam lagoon ecosystem) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Sriyanie Miththapala (compiler) IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Sri Lanka Country Office October 2011 i Disclaimer and copyright text This publication has been made with the financial support of the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation for Development (AECID) through an FAO trust-fund project, the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (RFLP) for South and Southeast Asia. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the opinion of FAO, AECID, or RFLP. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational and other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. -

Of Sri Lanka: a Taxonomic Research Summary and Updated Checklist

ZooKeys 967: 1–142 (2020) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 CHECKLIST https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist Ratnayake Kaluarachchige Sriyani Dias1, Benoit Guénard2, Shahid Ali Akbar3, Evan P. Economo4, Warnakulasuriyage Sudesh Udayakantha1, Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo5 1 Department of Zoology and Environmental Management, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China3 Central Institute of Temperate Horticulture, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, 191132, India 4 Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Onna, Okinawa, Japan 5 Department of Zoology, Government Degree College, Shopian, Jammu and Kashmir, 190006, India Corresponding author: Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo ([email protected]) Academic editor: Marek Borowiec | Received 18 May 2020 | Accepted 16 July 2020 | Published 14 September 2020 http://zoobank.org/61FBCC3D-10F3-496E-B26E-2483F5A508CD Citation: Dias RKS, Guénard B, Akbar SA, Economo EP, Udayakantha WS, Wachkoo AA (2020) The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist. ZooKeys 967: 1–142. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 Abstract An updated checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Sri Lanka is presented. These include representatives of eleven of the 17 known extant subfamilies with 341 valid ant species in 79 genera. Lio- ponera longitarsus Mayr, 1879 is reported as a new species country record for Sri Lanka. Notes about type localities, depositories, and relevant references to each species record are given. -

NATURAL RESOURCES of SRI LANKA Conditions and Trends

822 LK91 NATURAL RESOURCES OF SRI LANKA Conditions and Trends A REPORT PREPARED FOR THE NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY AND SCIENCE AUTHO Sponsored by the United States Agency for International Development NATURAL RESOURCES OF SRI LANKA Conditions and Trends LIBRARY : . INTERNATIONAL REFERENCE CENTRE FOR COMMUNITY WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION (IRQ LIBRARY, INTERNATIONAL h'L'FERi "NO1£ CEiJRE FOR Ct)MV.u•;•!!rY WATEri SUPPLY AND SALTATION .(IRC) P.O. Box 93H)0. 2509 AD The hi,: Tel. (070) 814911 ext 141/142 RN: lM O^U LO: O jj , i/q i A REPORT PREPARED FOR THE NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY AND SCIENCE AUTHORITY OF SRI LANKA. 1991 Editorial Committee Other Contributors Prof. B.A. Abeywickrama Prof.P. Abeygunawardenc Mr. Malcolm F. Baldwin Dr. A.T.P.L. Abeykoon Mr. Malcolm A.B. Jansen Prof. P, Ashton Prof. CM. Madduma Bandara Mr. (J.B.A. Fernando Mr. L.C.A. de S. Wijesinghc Mr. P. Illangovan Major Contributors Dr. R.C. Kumarasuriya Prof. B.A. Abcywickrama Mr. V. Nandakumar Dr. B.K. Basnayake Dr.R.H. Wickramasinghe Ms. N.D. de Zoysa Dr. Kristin Wulfsberg Mr. S. Dimantha Prof. C.B. Dissanayake Prof. H.P.M. Gunasena Editor Mr. Malcolm F. Baldwin Mr. Malcolm A.B, Jansen Copy Editor Ms Pamela Fabian Mr. R.B.M. Koralc Word - Prof. CM. Madduma Bandara Processing Ms Pushpa Iranganie Ms Beryl Mcldcr Mr. K.A.L. Premaratne Cartography Mr. Milton Liyanage Ms D.H. Sadacharan Photography Studio Times, Ltd. Dr. L.R. Sally Mr. Dharmin Samarajeewa Dr. M.U.A. Tcnnekoon Mr. Dominic Sansoni Mr. -

ESOFT Metro Campus International Journal

ESOFT Metro Campus International Journal Publication of ESOFT Metro Campus Volume 1, Issue 1, November 2014 No: 29/1, Milagiriya Avenue, Colombo 4, Sri Lanka 1 Editorial and Review Board Dr. Dayan Rajapakse - Group Managing Director, ESOFT Metro Campus Mr. Nishan Sembacuttiaratchy - CEO, ESOFT Metro Campus Dr. Dilina Herathn- Academic Dean, ESOFT Metro Campus Dr. Shamitha Pathiratne - Head of Special Projects, ESOFT Metro Campus Editorial Coordinator Dr. Shamitha Pathiratne Copyright © 2014 ESOFT Metro Campus All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisherexcept as permitted under theIntellectual Property Act of Sri Lank, No. 36 of 2003. ISSN 2386-1797 When referring to this publication, please use the following: Name, title (2014). ESOFT Metro Campus International Journal, 2(1), pp. (use the online version pages). 2 Table of Contents Group Managing Director’s Message 5 C.E.O’s Message 6 Academic Dean’s Message 7 Editor’s Column 8 Extended Embedding Capacity with Minimum Degradation of Stego Image Naveed Mustafa, Muhammad Bilal Iqbal Muhammad Asif and Abdul Jawad 9 Effectiveness of Governance and Accountability Mechanism for Local Governments in Sri Lanka – Interconnectivity Development Program M .M. Sarath Kumara 22 An Investigation of the Functions of Code Switching as an Instructional Strategy in Teachers’ Classroom Discourse at Tertiary Level W.I.Ekanayaka 34 Anthropogenic Impacts on Urban Coastal Lagoons in the Western and North-western Coastal Zones of Sri Lanka Jinadasa Katupotha 39 Sociological study on the success of the Activity Based Oral English L.