Water Management in Relation to Sdgs and National Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Evaluation of Amaltari Bufferzone Community Homestay of Kawasoti Municipality in Nawalpur, Nepal

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 7, Series 4 (July. 2020) 01-10 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Performance Evaluation of Amaltari Bufferzone Community Homestay of Kawasoti Municipality in Nawalpur, Nepal Dr. Rajan Binayek Pasa Assistant Professor at Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu ABSTRACT:This study analyzed performance evaluation of Amaltari Bufferzone Community Homestay (ABCH) of Kawasoti Municipality. This study followed post-positivist paradigm and survey methodology by applying evaluation indicators such as relevancy, efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability. The research issueshave been theorized from social capital, ecotourism, asset based community developmentand sustainability approach on development.The survey result shows that relevancy got highest mean value 3.9922 with std. deviation 0.90575 which is followed by impact mean value 3.7871 with std. deviation 0.78242 and sustainability mean value 3.6325 with std. deviation 0.79901. It signifies that majority of respondents are relatively satisfied with relevancy, impact and sustainability related variables. More so, effectiveness secured least mean value 3.5145 with std. deviation 0.85903 that is followed by efficiency mean value 3.6052 with std. deviation 0.78690. The value its self is not disagreed views of the respondents but from evaluation perspectives it requires more attention. However, ABCH has performed effectively due to the strong social capital, conservation and mobilization fund, good networks of physical assets, as well as quality leaderships that has brought positive impacts in community and social level. Finally, this study has high implications in the sector of improving the lives of people residing around bufferzone through the tourism activities. -

Tourism in Nepal: the Models for Assessing Performance of Amaltari Bufferzone Community Homestay in Nawalpur

NJDRS 51 CDRD DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/njdrs.v17i0.34952 Tourism in Nepal: The Models for Assessing Performance of Amaltari Bufferzone Community Homestay in Nawalpur Rajan Binayek Pasa, PhD Lecturer at Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu Email for correspondence: [email protected] Abstract This study assesses performance of Amaltari Bufferzone Community Homestay that received best homestay award in 2017. For the survey study, the datacollected from 236 sample respondents were theorized based on social capital, ecotourism, asset-based community development and sustainability approach that are then supported by the empirical findings. An index was developed to describe the overall performance of the homestay by compositing five thematic indexes: relevancy, efficiency, effectiveness, impact, sustainability. The index value 92.65 from the range of minimum 48 and maximum 240 for the overall performance provides the strong quantitative evidence to answer the question “why did Amaltari receive the best award among”. The multiple regression model (R-square value 0.99) for overall performance also proves that independent variables describe the dependent variables by 99 percent. Among the independent variables relevancy and effectiveness indexes are more likely to describe dependent variable- the overall performance index. The evidence shows that Amaltari homestay has performed well due to the technical/financial supports of WWF, proper mobilization/utilization of conservation fund and homestay community fund, strong social capital, and quality leadership that has transforming the livelihoods of Tharu, Bote and Mushar indigeneous people. However, they have some concerns like waste management in bufferzone areas, reviving the cultural organizations for preserving and transmitting culture from generation to generation, minimizing the modernization and demonstrative effects due to the excessive flow of the tourists and upgrading road connectivity. -

Determinants of Poverty, Self-Reported Shocks, and Coping Strategies: Evidence from Rural Nepal

sustainability Article Determinants of Poverty, Self-Reported Shocks, and Coping Strategies: Evidence from Rural Nepal Narayan Prasad Gautam 1,2 , Nirmal Kumar Raut 3 , Bir Bahadur Khanal Chhetri 2 , Nirjala Raut 2, Muhammad Haroon U. Rashid 1 , Xiangqing Ma 1 and Pengfei Wu 1,* 1 College of Forestry, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China; [email protected] (N.P.G.); [email protected] (M.H.U.R.); [email protected] (X.M.) 2 Institute of Forestry, Tribhuvan University, Pokhara 33700, Nepal; [email protected] (B.B.K.C.); [email protected] (N.R.) 3 Central Department of Economics, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur 44618, Nepal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-591-83780261 Abstract: This paper assesses the interrelationship between poverty, climatic and non-climatic shocks, and shock coping strategies adopted by farm-based rural households in Nepal. An analysis is based on a comprehensive data set collected from 300 randomly selected households from three purposively chosen villages of Gandaki province. The study utilizes binary and ordered probit regression models to analyze the determinants of poverty, shocks, and coping strategies. Findings reveal that the Dalit (ethnic group), large-sized, and agricultural households are more likely to be characterized as poor. The study further shows that majority of the households are exposed to the severe shock of climatic types. Patterns of shock exposure vary with the household’s characteristics. In particular, poor households in the hills primarily dependent on forest for livelihood are more likely to experience severe shocks. Further analyses indicate that the households ex-post choose dissaving, borrowing, Citation: Gautam, N.P.; Raut, N.K.; shifting occupation, and migration to cope with severe climatic shocks. -

In Gandaki Province Investment Opportunities in Gandaki Province

Welcome in Gandaki Province Investment Opportunities in Gandaki Province Dr. Giridhari Sharma Paudel Vice-chairman Policy and Planning Commission Gandaki Province, Pokhara, Nepal 11 February 2020 Main subjects highlighted in this presentation • Brief introduction of Gandaki Province • Poverty in Gandaki Province • Development aspiration of Nepal and Gandaki Province • Selected development targets • Seven key drivers and five enablers of prosperity • Existing situation, government sector plan, private sector plan and opportunity for investment to private sector in tourism, energy, agriculture, industry, infrastructure and human resources Brief Introduction of Gandaki Province • Area = 21,974 Square KM • % share of arable land in total land = 22.2 percent • Per capita availability of arable land is = 0.2 hectare • Household Numbers = 577,682 • Population (2018 Projected) =2.49 Million • Economically active population =57 % • Population density per square KM =114 persons • Ethnic groups = 22 • Local dialects = 22 • Life expectancy at birth =71.7 years • Total fertility rate per women =2.0 children • Total GDP 2017/018 = 2.57 Billion USD • Remittance = 1.7 Billion USD • GNI per capita income =1,043 USD • Climate = Sub-tropical to tundra • Perennial snowline = 16,000 feet and > Geography of Gandaki Province Geology of Gandaki Province Tibet China Koralla Jomsom Chame Beni Pokhara Bensisahar Baglung Kusma Tethys Himalaya Gorkha (Sedimentary rocks) Suangja Damauli Higher Himalaya (Metamorphic rocks) Lesser Himalaya (Metamorphic rocks) 70 km -

13Th Bulletin of FORWARD (April 01 2018 to July 16 2018).Pdf

FORWARD Nepal Bulletin – 13 April 01, 2018 – July 16, 2018 Patronage: Netra Pratap Sen, Executive Publication Committee: Mr. Ram Krishna Neupane Dr. Ujjal Tiwari, Ms. Ashmita Pandey FORWARD Nepal’s Bulletin five WHH‐ FORWARD partnership projects This is the thirteenth quarterly Bulletin of FORWARD implemented in Chitwan, in an analytical way. Nepal and includes a brief highlight of major activities WHH team appreciated the better sharing of implemented from April 01 to July 16, 2018. During learning and progress of those projects for a the period, some projects have been phased out and potential correction in future partnership. some new project initiated. The completed projects . Quarterly Programme Review and Planning are Meeting of FORWARD Nepal was held on June 28, 1. Girls’ Act Project (BALIKA SHAKTI) in Morang. 2018, in the chair of Prof. Dr. Durga Devkota, Vice‐chair. In the event, different 2. Gender Transformative ‐ Community Resilient programme/project activities, general (GET‐CR) Project in Morang and Sunsari. administrative and financial issues were reviewed 3. Enhancing Livelihoods of Smallholder Farmers in and discussed along with the sharing of effective Central Terai Districts of Nepal (ELIVES). feedback and suggestions for further During the same period, four New projects have been improvement. The event also remained a initiated: platform for the sharing of learnings from the national and international training attendees. 1. Dairy for Development in Nepal funded by Jersey Overseas Aid, UK in collaboration with Practical . For the programme transparency, FORWARD Action Nepal. Nepal organized a social audit at Jahada Rural Municipality‐06, Pokhariya, Morang in close 2. Girls Agency and Youth Empowerment Project coordination with Jahada Rural Municipality on (GAP) in Morang District. -

Annual Report 2016/17 Has Been Commenced in This Shape After Restless Engagement and Support from Different Personnel

i Foreword Multi dimensional Action for Development (MADE) Nepal has been contributing for the development of country since 1993. During the last 24 years of its journey, it has served in remote and rural communities of Nepal. Throughout the years, we have inclined to serve, with an integrated approach for poverty reduction. Significant achievements have been made in the area of livelihood improvement, food security, disaster risk management, local level institutional development and policy advocacy. Moreover, nutrition, sanitation, women empowerment, child development, gender empowerment and good governance are few cross cutting areas that MADE-Nepal has been covering. In this endeavor, MADE-Nepal has been privileged to serve more than 70,000 households and their families across 37 districts till date and we are honored to have been able to work together with hundreds of grassroots’ institutions across the country. We are pleased to present this annual report, which provides a brief account of the major projects implemented and the key results achieved by MADE-Nepal in the fiscal year 2016/17. It also includes executive summery comprising with food security and nutrition, disaster risk management, social mobilization and capacity building, institutional development and advocacy and networking. Similarly, organizational profile, geographical coverage, lesson learnt and celebration of silver jubilee are some of the major topics of the report. Sustainable livelihood assistance project implemented in partnership with CCS Italy since November 2016, Muchchok Recovery Project since 2015 funded by IM Swedish Development Partner, improving resilience through livelihood improvement since 2015 in partnership with LWR and strengthening small enterprise since 2016 at different districts had been came to end. -

ANSAB Annual Report 2075-76 (Final Copy)

Annual Report 2075/76 ANSAB ANSAB Annual Report Published by ANSAB P.O. Box 11035, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977 1 4497547/4478412 Fax: +977 1 4476586 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ansab.org.np © 2019 ANSAB This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. ANSAB would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from ANSAB. ANSAB Annual Report MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Partners, Donors and Friends, It gives me an immense pleasure to present another issue of ANSAB’s annual report that highlights our activities, achievements and financial situation in FY 2075/76. The past year marked important achievements that signify ANSAB’s strong and continuing recognition in its field, and our persistent focus on building prosperous communities through enterprise-oriented natural resource management. We implemented 10 projects in 2075/76 which have attained promising results and learning at the community level through our work on ecosystem-based commercial agriculture, forest certification of ecosystem services, value chain development, and resilient community development. We worked with the grassroots communities for their capacity development on sustainable forest management, farm and forest based enterprise-oriented activities along with the support on technical education to the poor students. We also worked at national level for the development of sustainable forest management certification standard, and at local level for the demonstration of a sustainable natural products-based enterprises and local economic development model that is environmentally sustainable, economically viable and socially beneficial. -

NEPAL NATIONAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER Standard Operating Procedure Transport and Storage Services December 2020

NEPAL NATIONAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER Standard Operating Procedure Transport and Storage Services December 2020 OVERVIEW This document explains the scope of the logistics services provided by the National Logistics Cluster, in support of the COVID-19 response in Nepal, how humanitarian actors and Nepal Government may access these services, and the conditions under which these services will be provided. The objective of the transport and storage services is to support humanitarian organisations and Government to establish a supply chain of medicines, medical supplies and equipment and humanitarian relief supplies mandated by the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) for Prevention of COVID-19 transmission, control and treatment to the hospitals and primary healthcare facilities. These services are not intended to replace the logistics capacities of responding organisations, nor are they meant to compete with the commercial market. Rather, they are intended to fill identified gaps and provide an option as last resort in case private sector service-providers are limited or unable to provide services due to the lockdown. These services are planned to be available until 28 February 2020, with the possibility of further extension. The services may be withdrawn before this date in part or in full, for any of the following reasons: • Changes in the situation on the ground • No longer an agreed upon/identified gap in transport and storage • Funding constraints The Logistics Cluster in Nepal will provide storage services (non-Cold Chain) for medicines, medical supplies and equipment and humanitarian relief supplies for COVID-19 response at three Humanitarian Staging Areas (HSA's) at Kathmandu Airport, Nepalgunj Airport and Dhangadhi Airport and transport services, provided free-of-cost to the users from Kathmandu to the Provincial capitals and the two provincial HSA's and from the provincial capitals to the district headquarters, as specified below. -

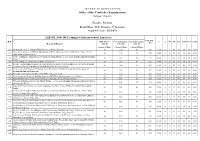

LEE Result 8Th Sem. B.Sc. Forestry 072-073 Final.Xlsx

Agriculture and Forestry University Office of the Controller Examinations Rampur, Chitwan Faculty : Forestry Result Sheet : B.Sc Forestry, 8th Semester Academic Year : 2072-073 LEE 401, 10(0+10) Learning for Entrepreneurial Experience Total (FM = Field Advisor Internal Examiner External Examiner % G GP CH CP TCH TCP OGPA R.N. 250) Research Report (FM=50) (FM=150) (FM=50) Obtained Marks Obtained Marks Obtained Marks 184 An Assessment of the Status of Bird Diversity in Bidur, Nuwakot 46 132 41 219 87.60 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 Assessment of Status and Habitat Distribution of Paha (Nanorana rarica ) in Rara Lake Shore (A Case 185 40 138 38 216 86.40 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 Study of Rara National Park) Status of Human-Common Leopard Conflict in Gulmi District (A Case Study from Resunga Municipality, 186 46 135 44 225 90.00 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 Gulmi) 187 Chemical Properties of Soil under Different Land Use 40 145 41 226 90.40 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 Resource Status, Ethno-botanical Uses and Market Potentiality of Seabuckthorn (A Case Study of Kalika 188 46 135 32 213 85.20 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 Community Forest, Pachaljharana Rural Municipality Ward-08, Kalikot) An Assessment of Roadside Plantation: Floral Diversity and People's Perception (A Case Study of 189 44 132 41 217 86.80 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 Kathmandu Ringroad Plantation) 190 Forest Investment Program (FIP) and REDD+ Linkage in Nepal 44 130 44 218 87.20 A 4 10 40 10 40 4.00 191 An Assessment of Capacity Building Program of REDD Implementation Center in Nepal 42 132 39 213 85.20 A 4 10 40 10 -

Statistices of Strategic Road

Copyright © 2018 Department of Roads All rights reserved Cover: Strategic Road Network of Nepal Pie Chart Showing Various Pavement Types of Strategic Road of Nepal Stacked Bar Chart Showing Strategic Road Length in Various Development Regions Published by: HMIS-ICT Unit, Department of Roads GIS Data: HMIS-ICT Unit, Department of Roads Personnel Involved: Mr. Mukti Gautam, DDG, Planning and Design Branch, DOR Mr. Dinesh Aryal, Unit Chief, HMIS-ICT Unit, DOR Mrs. Sajana Pokharel, Engineer, HMIS-ICT Unit, DOR Ms. Salina Dangol, Computer Engineer, HMIS-ICT Unit, DOR Mr. Prashant Malla, Team Leader/GIS Programmer Mr. Gambir Man Shrestha, Civil Engineer Ms. Prashanna Talchabhandari, GIS Engineer GIS data processing, road status update using route feature class and final GIS map and data preparation is done by AVIYAAN Consulting (P) Ltd, Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Better road planning is essential for safe, reliable and sustainable road development of the country. A good road data is of prime requirement for any effective road planning process. Availability of such data also reflects the performance of the road sector, which also helps in projecting overall growth of road network over the time. To disseminate this information Department of Roads (DoR) has been publishing Nepal Road statistics (NRS) every alternate years. Since 2004, the Nepal Road statistics (NRS) has been renamed as "Statistics of Strategic Roads Networks (SSRN)" focusing on data and information about strategic roads, while the local roads network (LRN) is now under the Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agriculture Roads (DoLIDAR). The present version of the SSRN is an updated version of 2017/18 Road Networks. -

Annual Report

Nepal ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Message from the Regional Director IM South Asia Need To Stay Strong, Now Cover Photo From left to right: Menuka Budhathoki, Kamala Rana, Manuka Pun (single women) and Sita Giri. More Than Ever Leaf plate is one of the materials made from tree leaves served as a plate to a meal. This is one of the environment friendly product. M Swedish Development Partner has been partners supported these families to even get government IM’s partner IRDC Nepal has been promoting working in Nepal since 2010. It has already resources and services for farming. climate resilience entrepreneurship in collaboration with local government. To fulfill entered in its strategic period from 2019-2023 the same objectives, IRDC Nepal supported and working towards empowering civil society This year’s report also has great results in our work leaf plate making machine and dais with towards social inclusion where we have contributed necessary training to the selected rights organizations, promoting social and economic holders from marginalized community. inclusion of the marginalized communities and to women decision making, combating gender-based Isupporting to create enabling environment for civil violence, ending-child marriages and caste-based society following the human rights-based approach. Our discrimination. Together with partners we reached target groups are women and youth from ex-Kamaiya directly to 1,224 women, girls, and youth through 69 and ex-Kamalari, Dalit, Madhesi, Muslim, Janajati groups. Today, these groups are working as vital platforms CONTENTS and other marginalized communities. We work with to discuss the situation of exclusion, discrimination, partner organisations in Dang, Kapilvastu in Lumbini violence, poverty, and empowerment. -

Assessment of Soil Organic Carbon Stock of Churia Broad Leaved Forest of Nawalpur District, Nepal

Grassroots Journal of Natural Resources, Vol. 2 No. 1-2 (2019) http://journals.grassrootsinstitute.net/journal1 -natural-resources/ ISSN: 2581-6853 Assessment of Soil Organic Carbon Stock of Churia Broad Leaved Forest of Nawalpur District, Nepal Bharat Mohan Adhikari*1, Pramod Ghimire1 1Faculty of Forestry, Agriculture and Forestry University, Hetauda, Nepal *Corresponding author (Email: [email protected]) How to cite this paper: Adhikari, B.M. and Ghimire, P. (2019). Assessment of Soil Abstract Organic Carbon Stock of Churia Broad The present article is based on the study carried out to Leaved Forest of Nawalpur District, Nepal. quantify aspect wise variation in Soil Organic Carbon Grassroots Journal of Natural Resources, (SOC) stock of Churia broad leaved forest in Bhedawari 2(1-2): 45-52. Doi: Community Forest of Nawalpur district, Nepal. The total https://doi.org/10.33002/nr2581.6853.02125 amount of SOC stock in upto 30 cm soil depth in Bhedawari Community Forest was found to be 33.91 t/ha. Aspect had made significant difference upon SOC stock with p value of 0.002 (p<0.05). The total SOC was higher in the northern aspect (36.83 ± 1.34 t/ha) than in the Received: 29 April 2019 Reviewed: 02 May 2019 southern aspect (30.98 ± 1.22 t/ha). Hence, soil carbon Provisionally Accepted: 10 May 2019 sequestration through community managed forest is a Revised: 17 May 2019 good strategy to mitigate the increasing concentration of Finally Accepted: 20 May 2019 atmospheric CO2. Published: 20 June 2019 Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and The Grassroots Institute.