Oral History Interview with Leonard Bocour, 1978 June 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Art Supplies for Abstract Painting (#1450)

Basic Art Supplies for Abstract Painting (#1450) Here is a list of all the essentials materials you need to start creating fabulous abstract paintings! I have added links so you can see the supplies. If you’re on a budget (like me:), I recommend looking for supplies at your local Michaels, Hobby Lobby or Joanne’s. I also love the art store Guiry's at 2121 S Colorado Blvd, Denver, CO 80222. Local Favorites Art Stores Guiry's: 2121 S Colorado Blvd, Denver 80222 Recreative: 765 Santa Fe Dr. Denver, CO 80204 (720) 638-3128 Affordable Scrapbooking: 17200 E Iliff, Aurora 80013 Tuesday Morning: 2890 S Colorado Blvd, Denver 80222 1. Gesso I use black gesso as my base layer to add depth to my paintings. • Liquitex BASICS Gesso Surface Prep; http://amzn.to/2htfSMI • DecoArt Deco Art White Gesso Americana Premium Acrylic Medium Paint Tube 2.5oz: https://amzn.to/2KtnRoh Black Gesso • DecoArt Deco Art Black Gesso Americana Premium Acrylic Medium Paint Tube 2.5oz • Deco Art Media Gesso, 4-Ounce, Black: https://amzn.to/2JKnBQJ • Art Alternatives Black Acrylic Gesso - 16oz Jar: https://amzn.to/2HIyRQQ Gesso is used to prep all surfaces. Used Gesso as a base layer for canvas. 2. Acrylic Paints Use student or artist grade paints. Make they’re Archival and Lightfast. • I love and use DecoArt® Americana® Premium™ Acrylic Paint: http://www.michaels.com/decoart-americana-premium-acrylic- paint/10515239.html?cm_mmc=PLASearch-_-google-_- MICH_National_PLA_Shopping_Null_Null_Crafts+and+Hobbies_RLSA-_-crafts- and-hobbies-craft-paint-RLSA&gclid=CjwKCAjwoKDXBRAAEiwA4xnqv4hFQY- TRVUnOBB2bV0ebUKlvvoEsVi8r0NgNq9HGnCBzghLZIZRZBoCiHEQAvD_BwE • I also use Master Touch Paints from Hobby Lobby Craft store. -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

Download Supply List

Awaken your senses to the beautiful symphony that arrives with each Spring. The wonder and awe of nature is the inspiration for this course. We will explore the colours and themes of the season through beautiful florals and sweet garden visitors. Special attention will be given to colour techniques while refining offhand flourishing skills. This course assumes that the student knows the basic pressure and release strokes of the pointed pen. Bring a sense of play with you as we welcome the Spring with these bright and beautiful designs. Supply List: Instructor’s Note: Use what you have on hand. It is not necessary to use the same papers and supplies that I use. Experiment with what you have as you explore these techniques. The only absolute on this list is waterproof ink if you are going to combine your flourishes with watercolour. If you cannot find the suggested waterproof inks, try an acrylic brown ink such as FW or Liquitex. The lines will not be as fine, but the ink will not run when water is added. Practice Paper ( Maruman Imagination suggested), Pencil, Eraser, ruler Practice ink such as Walnut will work for introductory exercises A few coloured pencils in floral colours Note taking supplies Straight pen holder with your favourite nib ( Hunt 22, Hunt 101, Gillott 404 or Zebra G suggested) Waterproof Ink: McCaffery Brown, McCaffery Black or Ziller Buffalo Brown are suggested for the Line and Wash technique Any brand of watercolour that you have for florals. John Neal carries a dot card of my favourite Daniel Smith watercolours. -

Art Hazards List

ART AND CRAFT MATERIALS THAT CANNOT BE PURCHASED FOR USE IN KINDERGARTEN THROUGH 6TH GRADE Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment – California Environmental Protection Agency September 2016 California Education Code Section 32064 prohibits schools from purchasing art or craft materials containing a toxic substance for use by students in kindergarten and grades 1-6 (K- 6). The law also requires the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) to develop a list of products that schools cannot purchase for use by students in K-6. This list (attached) is intended to assist schools, school districts, and governing authorities of private schools in complying with the purchasing requirements. Purchasers must ensure that all art and craft materials to be used by students bear a statement of conformity to ASTM D-4236 (Standard Practice for Labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards), as required by federal law. Items to be used by students in K-6 must not bear acute or chronic health hazard labels. Although not required by law, avoiding art materials that bear acute or chronic health hazard labels when purchasing for grades 7-12 is a good precautionary measure. Schools are encouraged to inventory existing art and craft supplies and remove materials bearing health hazard labels from K-6th grade classrooms. For further information, please see Art and Craft Materials in Schools: Guidelines for Purchasing and Safe Use, accompanying this list or available online (see below). OEHHA compiled the attached list based on product evaluations conducted by other entities1 according to federal requirements. Other art and craft materials that can be listed are products recalled in the past five years2 (no such products are listed at this time), as well as those brought to OEHHA’s attention as bearing health hazard labels. -

Course Syllabus Page 1

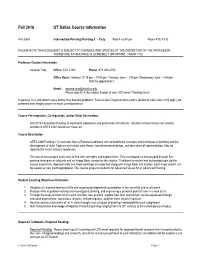

Fall 2016 UT Dallas Course Information Arts 3369 Intermediate Painting/ Painting 2 - Tady Wed 4 - 6:45 pm Room ATC 4.910 PLEASE NOTE THIS DOCUMENT IS SUBJECT TO CHANGES AND UPDATES AT THE DISCRETION OF THE PROFESSOR, THEREFORE ATTENDANCE IS EXTREMELY IMPORTANT. THANK YOU. Professor Contact Information Lorraine Tady Office: ATC 4.903 Phone: 972-883-6753 Office Hours: Monday 12:15 pm – 12:45 pm; Tuesday 3 pm – 3:45 pm; Wednesday 3 pm – 3:45 pm; AND by appointment. Email: [email protected] Please specify in the subject header of your UTD email “Painting Class” In general, let’s talk about issues before they become problems. Face-to-face/ in-person discussions (before or after class or by appt.) are preferred over lengthy phone or email correspondence. Course Pre-requisites, Co-requisites, and/or Other Restrictions Arts 2316 Foundation Painting or equivalent experience and permission of instructor. Students should not be concurrently enrolled in ARTS 4368 Advanced Visual Art. Course Description ARTS 3369 Painting 2 (3 semester hours) Explores traditional and nontraditional concepts and techniques of painting and the development of style. Topics may include color theory, two-dimensional design, and the nature of representation. May be repeated for credit (6 hours maximum). The course encourages each artist to find their strengths and explore them. This investigation is encouraged through five painting strategies or catalysts and an Image Book created by the student. Traditional materials and technology tools aid the course experience. Approximately 3-4 major paintings are expected along with Image Book and studies. Each major project can be viewed as your painting proposal. -

HOME CRAFTING GUIDE at Home All Day? We’Re Here for You

WEEK 7 HOME CRAFTING GUIDE At home all day? We’re here for you. We know this is a tough time for many of us around the world and it’s hard not to feel anxious and overwhelmed. To help you get through the long days, we invite you (and your loved ones) to craft with us! We’ve curated our favorite classes to help you center your mind, start a new hobby, keep your hands busy, and get lost in your own creative headspace – even for just a few minutes. And for those who are home with young ones, we guarantee this is screen time you can feel good about. Remember... You're more creative than you think! HOME CRAFTING GUIDE 2 WEEK 7 Dear Diary Daily Quilting Challenge with Anna Maria Horner https://www.creativebug.com/classseries/ single/dear-diary-daily-quilting-challenge Skill level: Intermediate Video duration: 2 hours Materials: - Straight pins - About 10 yards of quilting weight cotton - Sewing machine fabric (Anna Maria uses the following - Hand-sewing needles colors: rust, black printed, solid black, - Scissors leopard, maroon, lime green, blue and - Rotary cutter and mat yellow plaid, medium blue, pink plaid, - Ruler and templates purple, red, coral/green floral, stripe fabric, - Marking tool light blue, cream, pale pink and yellow, - Fabric glue stick dark grey, yellow, pink, rust, coral, pink and - Aurifil 50 weight thread in a dark and light white pattern, light grey, solid blue, blue - Iron and ironing surface and aqua pattern, and green) - Fusible web for machine appliqué (Anna * Includes pattern PDF Maria uses Steam-a-Seam) Paper templates are included in the PDF but you can find acrylic templates for the appliqué at https://www.annamariahorner.com/quilt-patterns-templates/in-bloom-acrylic- templates, and mylar templates at https://www.annamariahorner.com/quilt-patterns- templates/in-bloom-myylar-templates. -

Landscape Plein Air Painting Halcyon Teed If You Choose to Use Paint, Purchase Student Grade Oil Or Acrylic Paints. Winsor &Am

Landscape Plein Air Painting Halcyon Teed If you choose to use paint, purchase Student Grade Oil or Acrylic Paints. Winsor & Newton WINTON Oil Paint is good. Whatever brand you choose I recommend the following colors or the equivalent in 37ml tubes. HUE is a synthetic student grade version of the color and quite a bit cheaper. Oil Paints: Cadmium Lemon Yellow HUE Cerulean Blue HUE Cadmium Yellow Medium HUE Ultramarine Blue HUE Cadmium Orange HUE Viridian [green] HUE Cadmium Red Light HUE or Vermilion HUE Titanium White Larger tube is better Alizarin Crimson HUE Sets of oil paints maybe cheaper but will contain colors that you don’t need like ochre, umber and black as well as Not include colors you need. WATER MIXABLE OIL Paints are also available and should have the same names. SOLVENT and accessories: Turpenoid for Oil based paint [no odor] Palette Paper pad or if wood [must be varnished] {freezer wrap can be used} Rags or paper towels, Liquid tight Jar for Turpenoid [glass is preferable] Plastic Palette knife or equivalent to clean palette. OR Acrylics: Several brands are good. Liquitex, Grumbacher Academy, Royal Talens. Regular tubes about 60ml, 75ml to 95ml. Liquitex makes a Basic Set of 12 color 22ml tubes but are quite small. Basically the same colors as above for Oil Paint. Manufacturers have their own naming conventions which is confusing. If no Viridian is available look for Hooders Green. SOLVENTS and accessories: Water, Glass or Plastic Water Container, Palette [ceramic metal or plastic] Palette Paper pad {freezer wrap can be used} AND Brushes: Purchase Hog Bristle FLAT brushes. -

Itʼs All About The

ITʼS ALL ABOUT THE WINSOR & NEWTON Winton Oil Colours 37ml Buy any 6* and get a Bonus Titanium White 200ml, valued at over BONUS $44 – FREE TUBE $ 15.30ea *37ml tubes, colour of your choice. REEVES TOMBOW WINSOR & NEWTON Fine Artist Quality Dual Brush Pen Sets Professional Watercolours Acrylic Paints 200ml of 6 & 10 5ml & 14ml Strong, vibrant colours. Flexible Brush and Fine Tip in one Pen. Spend $40 or more on Professional Watercolour Water-based and quick drying. Blendable, water-based Ink. Tubes* and get a Bonus Winsor & Newton Suitable for a variety of techniques Perfect for lettering, Watercolour Visual Diary, A5, 200gsm, and surfaces. illustrations, colouring valued at over $21 – FREE and stamping. NOW FROM % FROM BONUS NOW FROM 10 $ .70ea $ VISUAL 12 $ .60 OFF 19.95ea 200ml Standard Colours 37 Series 1, 5ml DIARY Packaging may vary Set of 6 *5ml or 14ml tube, colour of your choice $2 OFF JASART Individual Pencils Buy any 5 and get a BONUS Bonus Reeves Layflat JOURNAL Visual Journal Ivory valued at over $7 – FREE FROM $ .95ea 1 Drawn with J Sketch Graphite Pencils asart See page 2 for details WINSOR & NEWTON WINSOR & NEWTON WINSOR & NEWTON Cotman Watercolour Cotman Watercolour ProMarkers & BrushMarkers Brush Pen Set 45 Half Pan Studio Set Twin tipped and alcohol-based with streak-free coverage. 12 Half Pans plus a Water Brush Pen. NOW Buy any 3 NOW $ .95 and get an $ 145 HOT 69.95 0421080 Extra 2 – FREE* 0419090 PRICE NOW $ 10.25ea *Colour of your choice. 2 HOT BONUS PRICE MARKERS WINSOR & NEWTON Artisan Water Mixable WINSOR & NEWTON Oil Colours 37ml Brushes Genuine Oil Colour. -

Winsor & Newton

NEW Artwork by David Becerra WINSOR & NEWTON BrushMarker Tour de Force VALUED 42 Piece Set This impressive gift set contains: AT OVER BrushMarkers x 40, Marker Pad 50 sheets and a Weekender Bag. $500 ONLY $149 0066160 NEW REEVES Pencil Wooden Gift Sets 34 Pieces Premium quality Wooden Box Pencil Sets in both Colour and Watercolour assortments. Contains: Pencils x 30, Pad, Eraser, Sharpener and Wooden Box. 0063220 Colour Pencils 0063240 Watercolour Pencils ONLY $59.95ea JASART Byron Paint Starter Sets Everything you need to start painting. Contains: Paint Tubes 12ml x 6, Canvas Panel 5” x 7” and a Brush. 0063180 Acrylic NEW 0063190 Watercolour 0063200 Oil ONLY $15.95ea HOT PRICE WINSOR & NEWTON Cotman Watercolour 45 Half Pan Studio Set A large set containing 45 Cotman Half Pans. NOW $139.95 0421080 BONUS MARKER LIQUITEX Acrylic Ink 30ml Intense, lightfast colours. Permanent & water resistant. BUY ANY 2 LIQUITEX INKS AND GET A 4MM PAINT MARKER, VALUED AT OVER $14 – FREE!* ONLY $17.95ea *Bonus 4mm Acrylic Marker - Colour of your choice. WINSOR & NEWTON Professional Watercolour Field Box* Contains: Half Pans x 12, Pocket Brush, Sponge, Water Bottle and Container. BONUS $219.95 0179451 SERIES 7 SABLE NO. 4 BRUSH & HAND-PAINTED PALETTE BONUS valued at over BONUS when you purchase any of these selected Winsor & Newton Sets*. $139 Total bonus valued at over $139 – FREE* *While stocks last. Acclaimed as the world’s finest watercolour brush, Series 7 Kolinsky Sable Brushes are handmade in England. Experience 96 Winsor & Newton Professional Watercolours Winsor & Newton Professional Watercolours are officially endorsed by featured in the Colour Palette. -

PDF Document

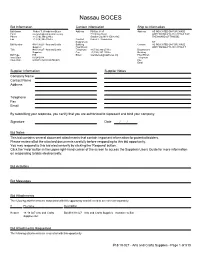

Nassau BOCES Bid Information Contact Information Ship to Information Bid Owner Robert T. Wendelken Buyer Address PO Box 9195 Address AS INDICATED ON PURCHASE Email [email protected] 71 Clinton Road ORDERS ISSUED AS A RESULT OF Phone +1 (516) 396-2240 x Garden City, NY 11530-9195 THE AWARD OF THIS BID. Fax +1 (516) 997-1053 x Contact Robert T. Wendelken Department NY Bid Number #18/19-027 - Arts and Crafts Building Contact AS INDICATED ON PURCHASE Supplies Floor/Room ORDERS ISSUED AS A RESULT Title #18/19-027 - Arts and Crafts Telephone +1 (516) 396-2544 x Department Supplies Fax +1 (516) 997-1053 x Building Bid Type ITB Email [email protected] Floor/Room Issue Date 05/24/2018 Telephone Close Date 6/7/2018 02:00:00 PM (ET) Fax Email Supplier Information Supplier Notes Company Name Contact Name Address Telephone Fax Email By submitting your response, you certify that you are authorized to represent and bind your company. Signature Date / / Bid Notes This bid contains several document attachments that contain important information for potential bidders. Please review all of the attached documents carefully before responding to this bid opportunity. You may respond to this bid electronically by clicking the 'Respond' button. Click the 'Help' button in the upper right-hand corner of the screen to access the Suppliers Users Guide for more information on responding to bids electronically. Bid Activities Bid Messages Bid Attachments The following attachments are associated with this opportunity and will need to be retrieved separately -

Supply List Information for Beginning/Intermediate Painting Students

Supply List Information for Beginning/Intermediate Painting Students For painting you will need to purchase paints, brushes, and a canvas pad or watercolor sketchpad and block. Your personal budget, your skill level, and your interest should dictate how much you choose to spend on these supplies. It can be done very economically or expensively. Paints, brushes, canvas board/pads and watercolor paper can be purchased at United Art and Education (online or at the store on route 42), Michaels, and Hobby Lobby. Online painting supply purchases can be made at Utrecht, Dick Blick, Sax Arts and Crafts, Cheap Joe’s, etc. Paints: Acrylic tube paints, 2 ½ oz. or 4 oz., in red, yellow, blue, white, and black. (For the cheapest version, use student grade tubes in 2-4 ozs.) Watercolor tube paints in red, yellow, blue, white, and black. Some artists will purchase the secondary colors, orange, green, and violet, as well. Some names you will see are Thalo red, alizarin crimson, red madder alizarin, Naples yellow, cadmium yellow, cerulean blue, cobalt blue, hooker’s green dark/light, sap green, etc. You will notice that some colors are bright and some are dull. Try to stick with bright colors for your initial purchases. In acrylic paint, it is nice to also buy orange, green, and violet but only necessary if your primary colors are too warm to mix (a red or yellow that is too “orangey”). Red oxide and yellow oxide are nice to have but not a must. Red oxide and black mix to make a nice brown but brown can be mixed from your primaries as well.