Television Across Europe: Regulation, Policy and Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soluzioni Hospitality Scopri I Prodotti Maxital

SOLUZIONI HOSPITALITY SCOPRI I PRODOTTI MAXITAL ® ELECTRONIC ENGINEERING LO SAPEVI? Con il passaggio allo standard di trasmissione DVB-T2 (HEVC H.265) previsto per giugno 2022, tutte le televisioni che non supportano tale codifica non saranno più in grado di ricevere alcun canale. L’utilizzo di una centrale modulare permette di assicurare la visione di tutti i canali anche dopo lo switch off senza dover sostituire i televisori o dover installare ricevitori in ogni stanza! A SERVIZIO DEGLI OSPITI Maxital offre soluzioni complete e personalizzabili per la realizzazione di impianti per la distribuzione centralizzata dei servizi televisivi da satellite, da digitale terrestre o dati all’interno di contesti Hospitality come hotel, campeggi, strutture commerciali, ospedali o carceri, dove sono distribuiti segnali televisivi tradizionali con l’aggiunta di segnali in lingua straniera. SOLUZIONI PERSONALIZZATE PER HOTEL Scegli la soluzione Hospitality TV-SAT di MAXITAL che fa per te. Con l’utilizzo di una centrale modulare è possibile ricevere e distribuire canali satellitari, canali TivùSAT o entrambi, ottenendo il meglio dei canali TV-SAT sia italiani che stranieri. QUALI SERVIZI È POSSIBILE DISTRIBUIRE? FTA (Free SAT) PIATTAFORMA TIVÙSAT “Free-to-air” (FTA), sta ad indicare la trasmissione “free”, Tivùsat la piattaforma digitale satellitare gratuita italiana ovvero gratuita e non criptata di contenuti televisivi e/o nata per integrare il digitale terrestre dove non è presente radiofonici agli utenti. una buona copertura. Tivùsat trasmette dai satelliti Hot Bird Le soluzioni FTA offrono ua vasta scelta di canali (13° Est) e richiede l’utilizzo di una smartcard tivùsat che internazionali per poter soddisfare ogni richiesta degli ospiti. -

MEDIANE Media in Europe for Diversity Inclusiveness

MEDIANE Media in Europe for Diversity Inclusiveness EUROPEAN EXCHANGES OF MEDIA PRACTICES EEMPS Pair: CMFE 13 OUTPUT MIGRATION POLICIES IN COMPARISON SUMMARY 1. Exchange Partners Partner 1 Partner 2 Name and Surname Marina LALOVIC Gervais NITCHEU Job title Journalist Journalist Organisation / Media Radio RAI 3 France Télévisions (Output never finalised) 2. Summary The goal of our media exchange was to compare the immigration policies and political strategies between Italy and France. My media report consists in a 27 min radio documentary. It starts with a series of vox pops of the citizens of the multicultural district in Paris (La Villette) who all respond to the same question: Is France a racist country? How is life for immigrants in Paris? Rama Yade’s interview follows ordinary citizens’ opinion. A former Minister of the Sarkozy’s government explains how and why she represented a symbol of diversity in this government adding that she just wanted to be a symbol of French citizens as a whole. So she confesses that being considered an ordinary female politician, wasn’t that easy. Rama Yade also gives us an idea of the French model of immigration. The opi nions of some minority groups are reflected through the interviews with the most significant representatives of the Turkish community in Paris. Documentary than continues with the vox pops of the citizens interviewed in one of the most multicultural districts in Rome: Piazza Vittorio. Rama Yade’s Italian counterpart is former Italian Minister for integration: Cécile Kyenge. She explains her work during the year in this first Ministry for Integration in Italy and why she was so important in promoting diversity not just to Italian citizens but also within politicians. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

RAI) on the Draft Waste Incidental to Reprocessing Evaluation for Vitrified Low-Activity Waste Disposed Onsite at the Hanford Site, Washington

Request for Additional Information (RAI) on the Draft Waste Incidental to Reprocessing Evaluation for Vitrified Low-Activity Waste Disposed Onsite at the Hanford Site, Washington Maurice Heath, David Esh, Karen Pinkston, Leah Parks, Steve Koenick, Chris McKenney Division of Decommissioning, Uranium Recovery, and Waste Management (DUWP) Office of Nuclear Material Safety and Safeguards (NMSS) U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) Thursday, November 19, 2020, 9:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. PDT 1 NRC’s Role at the Hanford Site NRC provides independent technical consultation in an advisory manner based on an interagency agreement with DOE. NRC is not part of the Tri-Party Agreement (DOE, EPA, and the State of Washington). NRC’s consultation typically includes: - Scoping meetings or technical exchanges - Document Review (WIR Evaluation, Performance Assessment (PA), etc.) - Requests for Additional Information (RAI) - NRC Technical Evaluation Report (TER) NRC does not have a regulatory or a monitoring role at the Hanford Site. 2 Criteria for Determining Reprocessing Waste is WIR (i.e., not High-Level Waste) From DOE Manual 435.1-1 Have been processed, or will be processed, to remove key radionuclides to the maximum extent that is technically and economically practical; and Will be managed to meet safety requirements comparable to the performance objectives set out in 10 CFR Part 61, Subpart C, Performance Objectives Waste will be incorporated in a solid physical form at a concentration that does not exceed the applicable concentration limits for Class C low-level waste 3 Other Considerations for the Review DOE indicated that although the entire draft WIR evaluation is subject to consultation, DOE requested emphasis on criteria 2 (performance objectives) over criteria 1 (removal of key radionuclides). -

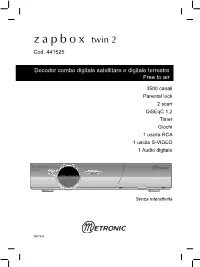

Zapbox Twin 2 Cod

zapbox twin 2 Cod. 441525 Decoder combo digitale satellitare e digitale terrestre Free to air 3500 canali Parental lock 2 scart DiSEqC 1.2 Timer Giochi 1 uscita RCA 1 uscita S-VIDEO 1 Audio digitale TNT/SAT Senza interattività MET632 DA LEGGERE ATTENTAMENTE Per pulire il vostro decoder o il telecomando non usare nè solventi nè detergenti. E’ consigliato l’utilizzo di uno straccio asciutto o leggermente umido per togliere la polvere. Secondo i requisiti della norma EN 60065, prestare particolare attenzione alla seguente guida di sicurezza. Non ostruire le aperture per la ventilazione con oggetti come giornali, vesti- ti, tende ecc.. Lasciare uno spazio di circa 5cm intorno all’apparecchio per consentire una corretta ventilazione. Non posizionare l’apparecchio vicino a oggetti infiammabili come candele accese. Per ridurre il rischio di fuoco o scossa elettrica, non esporre l’apparecchio a gocce o schizzi di alcun liquido e assicurarsi che nessun oggetto contenente liquido, come bicchieri e vasi, siano posizionati sull’apparecchio. Per rispettare l’ambiente, la batteria non va abbandonata: ne’ lungo le strade, ne’ dentro i cassonetti per i normali rifiuti solidi urbani. La batteria va posta negli appositi siti messi a disposizio- ne dai Comuni o nei contenitori che gli operatori della Grande Distribuzione Organizzata mettono a disposizione presso i loro punti vendita (applicabile soltanto se il prodotto è venduto con batterie). Il telecomando necessita di due pile AAA 1.5 V. Rispettate la polarità indica- ta. Per rispetto dell’ambiente e per legge, non buttare mai le pile usate nella spazzatura. L’installazione e l’uso del decoder satellitare si basano su canali pre-program- mati. -

Tina Venturi

Tina Venturi Milano email: [email protected] blog: tinaventuri.it/blog website: tinaventuri.it telefono +39 347 730 6038 Tv Varietà 2012/16 Talent’s today – Membro giuria del 1996/97 Scherzi a parte – Canale 5 talent – Produzione Asa Polaris – 1996/97 State bboni – Antenna 3 Canale Italia 1996 Su le mani – Rai Uno 2004 Il Duello – Rai 2 1995 Quelli che il calcio – Rai Tre 1998 No panic! – Junior Tv 1995 La stangata – Italia 1 1998 Fantastica italiana – Rai Uno 1995 Telethon – Telemontecarlo – voce 1998 Comicissimo – Happy Channel 1993 Freddie Mercury – Italia 1 – voce 1997/98 Milano Bolgia Umana – Rai Uno 1993 Travolti da un insolito capodanno – 1997 Il Muro – Odeon Tv Italia 1 – voce 1997 Gran festa – Canale 10 Serie Tv e web 2016 ToyBoy – serie web tv – in lavorazione 2016 Virtuous Circle – serie web tv – in lavorazione 2015/16 Clouds – serie web animata – autrice e doppiatrice 2010/14 Love XXL – serie web tv – autrice e attrice 2010 Quelli dell’intervallo – Disney Channel – Regia di Laura Bianca 2009 Piloti – Rai Due – Regia di Celeste Laudisio 2009 Lo scontrino alla cassa – Regia di Ivaldo Rulli 2009 Quelli dell'intervallo “At Home 2” (già Fiore e Tinelli) – 1a serie – La signora Serena – Regia di Paolo Massari 2008 Fiore e Tinelli – 3a serie – Ginevra in “Amici e nemici”e altri episodi – Disney Channel – Regia di Paolo Massari 2008 Finalmente soli – Vari episodi – Canale 5 2004 Love Bugs – Italia 1 2004 Finalmente soli – 5a serie – Seduto sull'altra sponda – Canale 5 – Regia di Francesco Vicario 1998/01 Casa Vianello – Vari episodi – Canale 5 1998 La dottoressa Giò 2 – Rete 4 – Regia di Filippo De Luigi 1990 Cristina III (Cri Cri) CV Tina Venturi - p. -

Reports and Financials As at 31 December 2015

Financials Rai 2015 Reports and financials 2015 December 31 at as Financials Rai 2015 Reports and financials as at 31 December 2015 2015. A year with Rai. with A year 2015. Reports and financials as at 31 December 2015 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Rai Separate Financial Statements as at 31 December 2015 13 Consolidated Financial Statements as at 31 December 2015 207 Corporate Directory 314 Rai Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction Statements Statements 5 Introduction Corporate Bodies 6 Organisational Structure 7 Letter to Shareholders from the Chairman of the Board of Directors 8 Rai Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction 6 Statements Statements Corporate Bodies Board of Directors until 4 August 2015 from 5 August 2015 Chairman Anna Maria Tarantola Monica Maggioni Directors Gherardo Colombo Rita Borioni Rodolfo de Laurentiis Arturo Diaconale Antonio Pilati Marco Fortis Marco Pinto Carlo Freccero Guglielmo Rositani Guelfo Guelfi Benedetta Tobagi Giancarlo Mazzuca Antonio Verro Paolo Messa Franco Siddi Secretary Nicola Claudio Board of Statutory Auditors Chairman Carlo Cesare Gatto Statutory Auditors Domenico Mastroianni Maria Giovanna Basile Alternate Statutory Pietro Floriddia Auditors Marina Protopapa General Manager until 5 August 2015 from 6 August 2015 Luigi Gubitosi Antonio Campo Dall’Orto Independent Auditor PricewaterhouseCoopers Rai Financial Consolidated Financial Introduction Statements Statements 7 Organisational Structure (chart) Board of Directors Chairman of the Board of Directors Internal Supervisory -

Who Trusts Berlusconi? an Econometric Analysis of the Role of Television in the Political Arena

KYKLOS, Vol. 65 – February 2012 – No. 1, 111–131 Who Trusts Berlusconi? An Econometric Analysis of the Role of Television in the Political Arena Fabio Sabatini* I. INTRODUCTION Silvio Berlusconi has dominated Italian political life since he was first elected prime minister in 1994. He has been the third longest-serving prime minister of Italy, after Benito Mussolini and Giovanni Giolitti, and, as of May 2011, he was the longest-serving current leader of a G8 country. This political longevity is often difficult to understand for foreign political analysts. The former Italian prime minister has an extensive record of criminal allegations, including mafia collusion, false accounting, tax fraud, corruption and bribery of police officers and judges1. Recently, he has even been charged with child prostitution. In a famous editorial published in April 2001, the respected British newsmagazine The Economist stated that: “In any self-respecting democracy it would be unthinkable that the man assumed to be on the verge of being elected prime minister would recently have come under investigation for, among other things, money-laundering, complicity in murder, connections with the Mafia, tax evasion * Email: [email protected]. Postal address: Sapienza University of Rome, Faculty of Econom- ics, via del Castro Laurenziano 9, 00161, Roma – Italy. Department of Economics and Law, Sapienza University of Rome. European Research Institute on Cooperative and Social Enterprises (Euricse), Trento. The empirical analysis in this paper is based on data collected within a research project promoted and funded by the European Research Institute on Cooperative and Social Enterprises (Euricse), Trento. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the paper are solely of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Euricse. -

Anti-Gay, Sexist, Racist: Backwards Italy in British News Narratives

Filmer, D 2018 Anti-Gay, Sexist, Racist: Backwards Italy in British News Narratives. Modern Languages Open, 2018(1): 6, pp. 1–21, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3828/mlo. v0i0.160 ARTICLE Anti-Gay, Sexist, Racist: Backwards Italy in British News Narratives Denise Filmer University of Catania, IT [email protected] The Berlusconi years have witnessed Italy placed in the uncomfortable spotlight of the international media; however, now that Berlusconi’s power has waned, a timely reflection is due on the extent to which the vestiges of the former Premier’s cultural have coloured images of Italy in British news discourse. How far do cultural myths influence the selection, narration and reception of Italian news reported in British newspapers? Do Berlusconi’s verbal gaffes reverberate in the construal of newsworthiness and evaluative parameters, reinforcing and perpetuating stereotypes of Italians as a whole? These are the key issues this contribution attempts to address. Stemming from a broader research project on the representation of Berlusconi’s non politically correct language in the British press, this study examines the representation of certain aspects of Italian culture that have been the focus of British news narratives in recent years. Four recurring themes are explored and discussed: homophobia, racism, sexism and fascism. Implementing a critical discourse analysis approach, news texts retrieved from a cross-section of British newspapers reporting on Italian affairs are examined. The analysis then focuses on the invisibility of translation in reconstructing discursive events in news narratives across cultural and linguistic barriers, and suggests that decisions taken in translation solutions can reproduce and reinforce myths or stereotypes. -

Tv2000: Un Modello Privato

Tv2000: un modello privato di servizio pubblico Facoltà di Comunicazione e Ricerca sociale Corso di laurea in Comunicazione, valutazione e ricerca sociale per le organizzazioni Cattedra di Sociologia della Comunicazione Candidato Filippo Passantino 1655721 Relatore Christian Ruggero A/A 2018/2019 Indice + Introduzione………………………………………………………………….. P. 4 Cap. 1 – La televisione sociale in Italia 1.1. Una nuova narrazione del sociale: il caso del “Coraggio di vivere” ......…. P. 6 1.2. Gli approfondimenti sociali nelle emittenti pubbliche oggi ………………. P. 8 1.3. Gli approfondimenti sociali nella televisione commerciale ......…….......... P. 12 1.4. Gli approfondimenti sociali su Tv2000 ...……………………...…………. P. 14 1.5. Il servizio pubblico è fornito solo dalla televisione pubblica? …………… P. 16 Cap. 2 – Dal satellite al digitale: la novità sociale di Tv2000 nella televisione italiana 2.1 Storia e mission della televisione della Cei: da Sat2000 a Tv2000…….... P. 20 2.2 Il “servizio pubblico” negli approfondimenti di Tv2000……................... P. 21 2.3 L’approfondimento a trazione sociale: “Siamo Noi” ……........................ P. 24 2.4 Da cronisti a players, una “missione possibile”: l’impegno per i profughi nel Kurdistan e a Lesbo ...…………………...……………………………...... P. 29 2.5 Comunicare il sociale: il piano marketing…….......................................... P. 33 2.6 Ascolti e target di riferimento: il pubblico di Tv2000………......….......... P. 35 Cap. 3 – La prospettiva sociale dell’informazione: il Tg2000 3.1 L’informazione del tg di Tv2000 …...………………………...…….. P. 41 3.2 Le storie di solidarietà in un “post” …………….………………..…. P. 44 3.3 Le buone notizie tra Tg1 e Tg2000 …...………….…………………. P. 45 2 Cap. 4 – La comunicazione social(e) di Tv2000 4.1 La presenza di Tv2000 sui social network ……………………………... -

Report Prepared for Mediaset§ 3 June 2016

Development of the audiovisual markets and creation of original contents Report prepared for Mediaset§ 3 June 2016 Lear Via di Monserrato, 48 00186 - Rome tel. +39 06 68 300 530 fax +39 06 68 68 286 email: [email protected] § This is a working translation of the Study “Evoluzione dei mercati dell’audiovisivo e creazione di contenuti originali” dated 16 May 2016. Index 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 2. The audiovisual system: the birth of new models ......................................................................... 2 2.1. Media convergence ............................................................................................................................ 2 2.2. Audiovisual business models ............................................................................................................. 6 3. The regulatory asymmetry of the audiovisual markets ................................................................. 9 4. The enforcement of copyright .................................................................................................... 12 4.1. Methods and numbers in piracy ...................................................................................................... 12 4.2. Description of loss of earnings by channel of monetisation ............................................................ 15 4.3. Monitoring costs .............................................................................................................................