Principles of Patient Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patient Assessment?

EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIAN ‐ BASIC What is Patient Assessment? Why is Patient Assessment important? MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 2 What are the phases of patient assessment? Review of Dispatch Information Scene Survey Initial Assessment Focused History and Physical Exam Detailed Physical Exam Ongoing Assessment Communication Documentation MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 3 Why is the order of Patient Assessment important? Why is it necessary to develop a method of assessment and use that method on all patients? MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 4 SCENE SIZE‐UP INITIAL ASSESSMENT Trauma FOCUSED HISTORY & FOCUSED HISTORY & PHYSICAL EXAM PHYSICAL EXAM Patient Patient DETAILED DETAILED PHYSICAL EXAM PHYSICAL EXAM Medical ON‐GOING ASSESSMENT MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 5 Begin with receipt of call Location Incident Injured/Injuries MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 6 Continue En Route Further info from dispatcher Observe ▪ Smoke? ▪ Fire? ▪ High line wires? ▪ Railroads? ▪ Water? ▪ Industry? ▪ Other Public Safety units? MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 7 Upon Arrival Observe ▪ Overall scene ▪ Location of victim(s) ▪ Possible Mechanisms of Injury MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 8 Upon Arrival Observe ▪ Hazards ▪ Crowds ▪ HazMat ▪ Electricity ▪ Gas ▪ Fire ▪ Glass ▪ Jagged metal ▪ Stability of environment ▪ Traffic ▪ Environment MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 9 Ensure Safety ▪ Yourself ▪ Partner ▪ Other rescuers/Bystanders ▪ Patient MECTA EMS Learning Assistant 10 Call for assistance ▪ Other EMS Units ▪ Law Enforcement ▪ Fire Department ▪ -

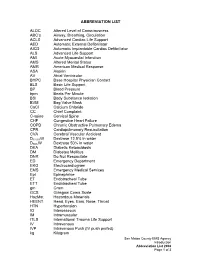

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

Career Technical Credit Transfer (CT²) Emergency Medical Technician-Basic (EMT-B) Career Technical Assurance Guide (CTAG) October 17, 2008

Adopted Career Technical Credit Transfer (CT²) Emergency Medical Technician-Basic (EMT-B) Career Technical Assurance Guide (CTAG) October 17, 2008 The following course or Career-Technical Assurance Number (CTAN) is eligible for transfer between career-technical education, adult workforce education, and post-secondary education. CTEMTB002 – Emergency Medical Technician – Basic (EMT-B) Credits: 7 Semester/10 Quarter Hours Advising Notes: Submitted course work must include proof of laboratory and clinical components. Those persons holding current Ohio certification as an EMT-Basic will be given what the receiving institution is offering as credit for its CT² approved EMT-B course. The awarding of credit for the EMT-B course of s t u d y m a y decrease the time to associate degree completion, when such a degree is offered, but will not replace any portion of the EMT-Intermediate or EMT- Paramedic curricula as the later two are separate courses of study. Prerequisite: Current Ohio EMT-Basic Certification Module I Preparatory Module II Patient Assessment Module III Airway and Cardiac Arrest Management Module IV Trauma Patient Management Module V Medical Patient Management Clinical Experience and/or Pre-Hospital Internship Minimum Hours = 120 Didactic 10 Clinical Experience and/or Pre-Hospital Internship Note: Credit hours assigned to CTANs are “relative values,” which are used to help determine the equivalency of submitted coursework or content. Once approved by a validation panel as a CT² course, students will be given what the receiving institution is offering as credit for its CT² approved course. The CTAN illustrates the learning outcomes that are equivalent or common in introductory technical courses. -

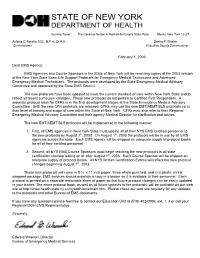

NY State-Wide EMT/AEMT BLS Protocols

STATE OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Corning Tower The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12237 Antonia C. Novello, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H. Dennis P. Whalen Commissioner Executive Deputy Commissioner February 1, 2003 Dear EMS Agency: EMS Agencies and Course Sponsors in the State of New York will be receiving copies of the 2003 version of the New York State Basic Life Support Protocols for Emergency Medical Technicians and Advanced Emergency Medical Technicians. The protocols were developed by the State Emergency Medical Advisory Committee and approved by the State EMS Council. The new protocols have been updated to meet the current standard of care within New York State and to reflect all recent curriculum changes. These new protocols do not pertain to Certified First Responders. A separate protocol book for CFRs is in the final development stages at the State Emergency Medical Advisory Committee. Until the new CFR protocols are released, CFRs may use the new EMT/AEMT BLS protocols up to their level of training and scope of care within the State of New York. CFRs may also refer to their Regional Emergency Medical Advisory Committee and their agency Medical Director for clarification and advise. The new EMT/AEMT BLS protocols will be implemented in the following manner: 1. First, all EMS agencies in New York State must update all of their NYS EMS certified personnel to the new protocols by August 1st, 2003. On August 1st, 2003 the protocols will be in use by all EMS agencies across the state. -

Emergency Care

Emergency Care THIRTEENTH EDITION CHAPTER 14 The Secondary Assessment Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Multimedia Directory Slide 58 Physical Examination Techniques Video Slide 101 Trauma Patient Assessment Video Slide 148 Decision-Making Information Video Slide 152 Leadership Video Slide 153 Delegating Authority Video Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Topics • The Secondary Assessment • Body System Examinations • Secondary Assessment of the Medical Patient • Secondary Assessment of the Trauma Patient • Detailed Physical Exam continued on next slide Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Topics • Reassessment • Critical Thinking and Decision Making Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved The Secondary Assessment Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Components of the Secondary Assessment • Physical examination • Patient history . History of the present illness (HPI) . Past medical history (PMH) • Vital signs continued on next slide Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Components of the Secondary Assessment • Sign . Something you can see • Symptom . Something the patient tell you • Reassessment is a continual process. Emergency Care, 13e Copyright © 2016, 2012, 2009 by Pearson Education, Inc. Daniel Limmer | Michael F. O'Keefe All Rights Reserved Techniques of Assessment • History-taking techniques . -

Patient Assessment-Trauma.Pub

Patient Assessment –Trauma 1 - Scene Size-Up • Body Substance Isolation [INCLUDES, BUT NOT LIMITED TO: GLOVES, MASK, GOWN, HEPA MASK] • Assess for scene safety [IF THE SCENE IS UNSAFE RETREAT TO A SAFE DISTANCE] • Identify Mechanism of Injury (MOI) Age, gender and race • Identify number of patients information • Determine need for additional resources [OTHER BLS, ALS, FD, PD, ETC.] may be used • Application of cervical spine immobilization, as necessary [MANUAL OR MECHANICAL] to identify a patient whose name cannot be 2 - Initial Assessment determined. • General Impression ♦Age, gender, race, position found ♦Determine MOI, if not already done A patient’s ♦Locate and treat life threats/quick CPR Check [EXSANGUINATING BLEEDING, NO PULSE OR RESPIRATIONS, ETC.] dentures ♦Verbalize a general impression of patient [“PALE LOOKING 35 Y/O MALE, BLEEDING FROM FOREHEAD”] may block the airway if • Mental Status they are not ♦ securely in place. Check for responsiveness, if not readily apparent ♦ Determine mental status/level of consciousness (LOC) on AVPU Scale Alert - correctly answers three questions related to Person, Place and Time Verbal - does not correctly answer all of above questions OR the patient only responds to verbal commands To better assess Pain - only responds to painful stimuli the Unresponsive - does not respond to any stimuli chest ♦ Determine chief complaint, if possible during the Initial Assessment, listen • Airway for lung sounds at ♦ the mid-axillary Can patient speak or cry? line. ♦ Are there any unusual breathing sounds? -

EMT Objectives

REQUIREMENTS: EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIAN EDUCATION PROGRAM INITIAL and REFRESHER Emergency Medical Technician programs must be based on this criteria and approved by the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services. Individuals completing non-approved programs shall be ineligible for licensure. 6/85, Revised 7/91, 5/95, 9/01, 9/06, 3/07, 11/12, 04/16, 10/2020 Authority: Act 368, P.A. 1978 as amended Table of Contents Baseline Vital Signs and SAMPLE History .....................................................................................12 MODULE 2 AIRWAY ......................................................................................................................13 Initial Assessment .........................................................................................................................13 MODULE 5 TRAUMA......................................................................................................................15 Injuries to the Head and Spine .....................................................................................................15 MODULE 6 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS .........................................................................................15 Pediatrics .......................................................................................................................................15 MODULE 7 OPERATIONS ..............................................................................................................15 Gaining Access ...............................................................................................................................16 -

Head to Toe Critical Care Assessment for the Trauma Patient

Head to Toe Assessment for the Trauma Patient St. Joseph Medical Center – Tacoma General Hospital – Trauma Trust Objectives 1. Learn Focused Trauma Assessment 2. Learn Frequently Seen Trauma Injuries 3. Appropriate Nursing Care for Trauma Patients St. Joseph Medical Center – Tacoma General Hospital – Trauma Trust Prior to Arrival • Ensure staff have received available details of the case • Notify the entire responding Trauma team • Assign tasks as appropriate for Trauma resuscitation • Gather, check and prepare equipment • Prepare Trauma room • Don PPE (personal protective equipment) • MIVT way to obtain history: Mechanism of injury Injuries sustained Vital signs Treatment given Trauma Trust St. Joseph Medical Center – Tacoma General Hospital – Trauma Trust Primary Survey • Begins immediately on patient’s arrival • Collection of information of injury event and past medical history depend on severity of condition • Conducted in Emergency Room simultaneously with resuscitation • Focuses on detecting life threatening injuries • Assessment of ABC’s Trauma Trust St. Joseph Medical Center – Tacoma General Hospital – Trauma Trust Primary Survey Components Airway with simultaneous c-spine protection and Alertness Breathing and ventilation Circulation and Control of hemorrhage Disability – Neurological: Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] or Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive [AVPU] Exposure and Environmental Controls Full set of vital signs and Family presence Get resuscitation adjuncts (labs, monitoring, naso/oro gastric tube, oxygenation and pain) -

Chest Injury Clinical Guidelines

Chest Injury Guidelines Contents: 1-3 Chest injury management Appendix 1 – Simple thoracosotomy without drain insertion Appendix 2 – Thoracotomy Appendix 3 – Evaluation of Pneumofix needle decompression device by CCPs Appendix 4 – The use of ultrasound devices Appendix 5 - Competency based process for autonomous finger thoracostomy WMAS Clinical Guidelines CG-CLI-009 I Version - 1 Guideline ID CG-CLI-009 Version Version 2 Title Chest Injury Approved by Immediate Care Governance Group Date Issued May 2017 Review Date March 2019 Directorate Immediate Care Governance Group Emergency Care Assistant Consultant paramedics X Authorised Staff Technician HEMS CCPs X For main Advanced Technician X Advanced practitioner X guideline approved by ICGG Student Paramedic X Doctor X Paramedic X Green – Deviation permissible for registered healthcare professionals Clinical Category with application of clinical judgement 1. Scope 1.1. These guidelines are written to support clinicians’ management of patients with chest injuries whilst being treated by West Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust responders. 2. Background 2.1. Chest injuries are significant contributors to major morbidity and mortality. Assessment of thoracic conditions is often difficult within the Prehospital environment and patients may not display classical signs of injury which may delay timely management. 3. Guidelines 3.1. Assessment 3.1.1. In accordance with JRCALC Guidelines; Thoracic Trauma, Trauma Emergencies 3.1.2. The following signs must be actively assessed and/or -

Of 35 DOT OBJECTIVES for THE

D.O.T. CURRICULUM and FUNDAMENTALS OF BASIC EMERGENCY CARE, 2E CORRELATION GUIDE DOT OBJECTIVES BEEBE/FUNK FOR THE EMT-BASIC FUNDAMENTALS OF BASIC EMERGENCY CARE, 2e PAGE MODULE 1 PREPARATORY Lesson 1-1 INTRODUCTION TO CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO EMERGENCY MEDICAL 4 EMERGENCY MEDICAL CARE SERVICES COGNITIVE OBJECTIVES 1-1.1 Define Emergency Medical Services OVERVIEW; Table 1-1 4; 9 (EMS) systems. (C-1) 1-1.2 Differentiate the roles and MODERN EMS 10-14; responsibilities of the EMT-Basic CHAPTER 2: MEDICAL RESPONSIBILITIES; Table 2-1; Table 19-27; 22 from other prehospital care 2-2 providers.(C-3) 1-1.3 Describe the roles and responsibilities Personal Safety 22 related to personal safety.(C-1) 1-1.4 Discuss the roles and responsibilities Crew, Patient and Bystander Safety 23 of the EMT-Basic towards the safety of the crew, the patient and bystanders.(C-1) 1-1.5 Define quality improvement and Continuing Education – Professional Development, Refresher Training 26-27; 28- discuss the EMT-Basic's role in the – Competency Assurance; Continuous Quality Improvement 31 process.(C-1) 1-1.6 Define medical direction and discuss MEDICAL DIRECTION 31 the EMT-Basic's role in the process.(C-1) 1-1.7 State the specific statutes and Refer to your state guidelines regulations in your state regarding the EMS system.(C-1) AFFECTIVE OBJECTIVES 1-1.8 Assess areas of personal attitude and Professional Attributes 23-27 conduct of the EMT-Basic.(A-3) 1-1.9 Characterize the various methods Univeral Access; Emergency Medical Dispatch 11-12 used to access the EMS system in your community.(A-3) PSYCHOMOTOR OBJECTIVES No psychomotor objectives identified. -

Pediatric Trauma Ryan Donlin, BSN, RN, CCRN Edited by Diana Priego BSN, RN, CCRN Objectives

Pediatric Trauma Ryan Donlin, BSN, RN, CCRN Edited by Diana Priego BSN, RN, CCRN Objectives • Review the current prevalence and leading types of Pediatric Trauma • Review and discuss the Pediatric trauma assessment - “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast” • Identify and evaluate Pediatric vs. Adult trauma differences • Examine injuries more commonly seen in the pediatric population • Analyze pediatric trauma prevention practices • Recognizing Child Abuse/Maltreatment Pediatric Trauma Trauma is the leading cause of childhood death and disability in the US. On average 12,175 deaths annually CDC Statistics – (2000-2006) Injury Deaths: • Death rate in Males were almost 2x that of females • #1 Leading cause of death for children were due to transportation related incidents (Occupant, Ped vs. Vehicle, Bicycle vs. Vehicle) • Leading cause of death by age group: < 1yr = Suffocation 1-4yr = Drowning 5-19yr = Occupant in MVC Death Rate Per 100,000 Population Buckle Up! And Buckle Up Correctly! More Nerd Stats • Blunt trauma accounts for more than 80% of all pediatric fatal injuries Body Part Rankings • #1 - Traumatic brain injury (TBI) • #2 – Thoracic • #3 – Abdominal Mechanism of Injury (MOI) Knowledge of the MOI allows for a high index of suspicion for the resultant injuries in the child. •MOI often reflects the age and developmental status of the child •External evidence of injury may be minimal as energy is often absorbed by underlying structures •MUST suspect underlying potential injuries!! Mechanisms of Injury The transfer of kinetic energy arises from several sources: • Blunt (injury to internal organs), • Penetrating (disruption of skin and organ integrity), • Acceleration-Deceleration (abrupt, forceful back and forth movement), • Crushing (direct compression of body structures). -

Alaska Prehospital Trauma Guidelines

PREHOSPITAL TRAUMA GUIDELINES FOR EMTs IN ALASKA Prepared by: Section of Injury Prevention and EMS Division of Public Health Department of Health and Social Services Box 110616 Juneau, AK 99811-0616 (907) 465-3027 (907) 465-4101 (fax) http://www.chems.alaska.gov Revised 1/07 INTRODUCTION These Trauma Guidelines were written in an effort to promote more efficient care and transportation of the severely injured trauma patient. They were designed to be used in the initial, and continuing, training of EMTs. These guidelines provide a framework for individual organizations and Physician Medical Directors for writing their own protocols. NOTHING in these guidelines authorizes an EMT to routinely perform a specific procedure on a particular patient. If a Medical Director wishes to authorize an EMT to perform any procedure, or give any medication that is outside the scope of practice for the EMT (as specified in 7 AAC 26.040) the physician must comply with 7 AAC 26.670. 7 AAC 26.670 requires a training and evaluation plan be submitted to the state, and after approval, list of individuals who have completed the proposed training and testing be submitted to the state. Signing standing orders alone is NOT adequate to add procedures and/or medications to an EMT’s scope of practice. The EMT-I, EMT-II, and EMT-III examinations for certification include questions based on these guidelines. These guidelines are meant to serve as a framework and provide a general approach to the trauma patient. To maximize the benefit of these guidelines on patient care, prehospital emergency care providers should discuss them with their physician medical directors so that, in addition to the recognition and management of the particular type of traumatic injury, each person involved in the prehospital care of the trauma patient knows: 1.