African Boundary Conflicts and International Mediation: the Absence of Inclusivity in Mediating the Bakassi Peninsula Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria - Accessibility to Emonc Facilities in the State of Cross River

Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities in the State of Cross River Last Update: March 2016 Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities for the Cross River State Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Measured indicators and assumptions .................................................................................... 5 3. Tool used for the different analyses: AccessMod 5.0 ............................................................. 7 4. Data and national norms used in the different analyses .......................................................... 8 4.1 Statistical Data ............................................................................................................... 9 4.1.1 LGA Number of pregnant women for 2010 and 2015 ........................................... 9 4.2 Geospatial Data ........................................................................................................... 12 4.2.1 Administrative boundaries and extent of the study area ...................................... 13 4.2.2 Geographic location of the EmONC facilities and associated information ......... 17 4.2.4 Transportation network ........................................................................................ 26 4.2.5 Hydrographic network ........................................................................................ -

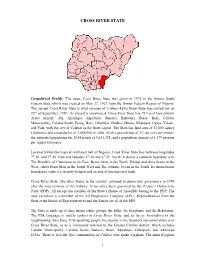

Cross River State

CROSS RIVER STATE Geopolitical Profile: The name Cross River State was given in 1976 to the former South Eastern State which was created on May 27, 1967 from the former Eastern Region of Nigeria. The current Cross River State is what remains of it when Akwa Ibom State was carved out on 23rd of September, 1987. As presently constituted, Cross River State has 18 Local Government Areas namely; Abi, Akamkpa, Akpabuyo, Bakassi, Bekwarra, Biase, Boki, Calabar Municipality, Calabar South, Etung, Ikom, Obanliku, Obubra, Obudu, Odukpani, Ogoja, Yakurr, and Yala; with the city of Calabar as the State capital. The State has land area of 23,000 square kilometres and a population of 2,888,966 in 2006. With a growth rate of 2.9 per cent per annum, the estimated population for 2014 stands at 3,631,328, and a population density of 1,579 persons per square kilometre. Located within the tropical rainforest belt of Nigeria, Cross River State lies between longitudes 7⁰ 50’ and 9⁰ 28’ East and latitudes 4⁰ 28’and 6⁰ 55’ North. It shares a common boundary with The Republic of Cameroun in the East, Benue State in the North, Ebonyi and Abia States in the West, Akwa Ibom State in the South West and The Atlantic Ocean in the South. Its international boundaries make it a security hotspot and an axis of international trade. Cross River State, like other States in the country, returned to democratic governance in 1999 after the interventions of the military. It has since been governed by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). -

NIGERIA: Registration of Cameroonian Refugees September 2019

NIGERIA: Registration of Cameroonian Refugees September 2019 TARABA KOGI BENUE TAKUM 1,626 KURMI NIGERIA 570 USSA 201 3,180 6,598 SARDAUNA KWANDE BEKWARA YALA DONGA-MANTUNG MENCHUM OBUDU OBANLIKU ENUGU 2,867 OGOJA AKWAYA 17,301 EBONYI BOKI IKOM 1,178 MAJORITY OF THE ANAMBRA REFUGEES ORIGINATED OBUBRA FROM AKWAYA 44,247 ABI Refugee Settlements TOTAL REGISTERED YAKURR 1,295ETUNG MANYU REFUGEES FROM IMO CAMEROON CROSS RIVER ABIA BIOMETRICALLY BIASE VERIFIED 35,636 3,533 AKAMKPA CAMEROON Refugee Settlements ODUKPANI 48 Registration Site CALABAR 1,058MUNICIPAL UNHCR Field Office AKWA IBOM CALABAR NDIAN SOUTH BAKASSI667 UNHCR Sub Office 131 58 AKPABUYO RIVERS Affected Locations 230 Scale 1:2,500,000 010 20 40 60 80 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official Kilometers endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Data Source: UNHCR Creation Date: 2nd October 2019 DISCLAIMER: The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. A technical team has been conducting a thorough review of the information gathered so as to filter out any data discrepancies. BIOMETRICALLY VERIFIED REFUGEES REGISTRATION TREND PER MONTH 80.5% (35,636 individuals) of the total refugees 6272 counteded at household level has been 5023 registered/verified through biometric capture of iris, 4025 3397 fingerprints and photo. Refugee information were 2909 2683 2371 also validated through amendment of their existing 80.5% information, litigation and support of national 1627 1420 1513 1583 586 VERIFIED documentations. Provision of Refugee ID cards will 107 ensure that credible information will effectively and efficiently provide protection to refugees. -

The Cross River Super Highway: Fact Sheet

The Cross River Super Highway: Fact Sheet TIMELINE After May 2015: Super highway construction announced severally by Governor FOREST ASSETS Ayade, together with the installation of a deep sea port in the mangroves. Cross River State is host to the largest remaining rainforests of Nigeria. September 2015: Groundbreaking ceremony and visit by President Buhari The Cross River National Park has two distinct, non-contiguous divisions: Oban postponed because of non-existing Environmental Impact Assessment. Re-routing and Okwangwo, with a total area of about 4,000 square km. Protected forests of highway to move it outside the National Park. also exist outside the boundaries of the National Park. In total, Cross River 20 October 2015: Buhari performs the groundbreaking ceremony at Obong State hosts at least 5,524 sq km of protected rainforests. Akamkpa LGA, Cross Rivers State. One of the highest bio-diversity forests in the world, Cross River State is home 22 January 2016: Cross River Government Gazette announces revocation of all to highly threatened species including Cross River gorilla, Nigeria-Cameroon occupancy titles within a 20 kilometre wide corridor of land along the highway chimpanzee, drill monkeys and many others, and hosts about 1,568 plant route. species, of which 77 are endangered including medicinal plants and orchids. February, 2016: Bulldozers enter the Ekuri-Eyeyeng, Etara and Okuni areas and Two new species of orchids were found to be unique to Cross River forests: start clearing and felling of trees. Communities in Old and New Ekuri prevent Tridactyle sp nov. and Hebenaria sp nov. bulldozers from logging in their forest. -

Anti-Bullet Charms, Lie-Detectors and Street Justice: the Nigerian Youth and the Ambiguities of Self-Remaking

At the International Conference, Youth and the Global South: Dakar, Senegal, 13 - 15 October 2006. Anti-Bullet Charms, Lie-Detectors and Street Justice: the Nigerian Youth and the Ambiguities of Self-Remaking Babson Ajibade Cross River University of Technology, Calabar, Nigeria. Abstract The failure of the Nigerian state, its police and judiciary to provide security has eroded citizenship trust. But this failure has tended to implicate the so-called ‘elders’ normally in charge of village, township and urban life-worlds. Disappointedly, Nigeria’s ‘young generations’ creatively assume unofficial yet central positions of ambiguity in the restoration of social order and security. In urban, peri-urban and rural locations ethnic militias and private youth gangs operate as alternative police and adjunct judiciary in place of the state’s failed institutions. These militia and youth gangs use guns, charms and violence to contest pressing concerns and negotiate contemporary realities. While processes of political economy and globalization remain unfavourable, youths – as agents and subjects of social change – are able to subvert status quo by deploying materials appropriated from the local and the global to define ambiguous positions. In one such hybridised situation, youths in Obudu1 have created a device they term ‘lie-detector’ – by fusing ideas gleaned from local and global media spaces. Using this device as central but unconventional social equipment and, drawing validation from traditional social systems, these youths are negotiating new selves in a contemporary milieu. Using the analysis of social practice and popular representation of youth roles, activities and initiatives in Nigeria, this paper shows how sociality and its contestation in urban life moves the Nigerian youth from the periphery to the centre of social, political and economic nationalisms. -

Evaluation of Intensity of Urinary Schistosomiasis in Biase and Yakurr Local Government Areas of Cross River State, Nigeria Afte

Research Journal of Parasitology 10 (2): 58-65, 2015 ISSN 1816-4943 / DOI: 10.3923/jp.2015.58.65 © 2015 Academic Journals Inc. Evaluation of Intensity of Urinary Schistosomiasis in Biase and Yakurr Local Government Areas of Cross River State, Nigeria after Two Years of Integrated Control Measures 1H.A. Adie, 1A. Oyo-Ita, 2O.E. Okon, 2G.A. Arong, 3I.A. Atting, 4E.I. Braide, 5O. Nebe, 6U.E. Emanghe and 7A.A. Otu 1Ministry of Health, Calabar, Nigeria 2Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, University of Calabar, Nigeria 3Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, University of Uyo/University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria 4Federal University, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria 5Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria 6Department of Medical Microbiology/Parasitology, University of Calabar, Nigeria 7Department of Internal Medicine, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Corresponding Author: H.A. Adie, Ministry of Health, Calabar, Nigeria ABSTRACT A parasitological mapping of urinary schistosomiasis using filtration method was conducted in Biase and Yakurr LGAs of Cross River State, Nigeria by the Neglected Tropical Diseases Control unit in collaboration with the schistosomiasis/soil transmitted helminths unit of the Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria in November 2012. The results of the study revealed a mean urinary schistosomiasis prevalence of 49% for the six schools under study in Biase and 30% for the six schools under study in Yakurr LGA. The mean ova load was 0.9 for males and 0.8 for females in the two LGAs. Integrated control measures put in place, included chemotherapy of infected individuals with praziquantel and health education on the predisposing factors responsible for the transmission of urinary schistosomiasis. -

Bakassi Thesis Final

Chapter One General Presentation 1.1 Introduction The eruption of most territorial conflicts around the world generally stems from ideological or religious differences, nationalism, colonialism, and competition for natural resources. While some easily degenerate into prolonged conflicts or wars that eventually involve the use of heavy weaponry, others get settled through diplomatic moves, coercion by the international agencies or agreements. With a compromised historical heritage, it is not surprising that post-colonial Cameroon and Nigeria were marred by a number of border disputes but the territorial claim surrounding the Bakassi Peninsula stands unique; not only was it the most serious of all disputes between the two countries, but it ended in the most spectacularly unexpected manner against all odds. The Bakassi crisis took public stage when it became clear that it was very rich in natural gas, petroleum and fishing. It was even more so after the discovery of potential oil reserves in its surroundings. The mounting of tension between the two countries in the 1990s urged the Cameroonian government to adopt a legal approach by filing a law suit to the ICJ against the Nigerian Federation on March 24, 1994 in which Cameroon sought an injunction for the expulsion of Nigerian forces, which was said to be occupying the territory. Nevertheless, the conflict can be traced back to the colonial era. With the Natives’ loss of control over their lands in the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, new boundaries emerged that did not consider ethnic groupings. These borders were sustained through agreements between the colonial powers, followed by the League of Nations and lastly the UN. -

THE RELIGIOUS RESPONSE to MIGRATION and REFUGEE CRISES in CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Udoh, Emmanuel Williams, Ph. D Department

FAHSANU Journal Journal of the Arts /Humanities Volume 1 Number 2, Sept., 2018 THE RELIGIOUS RESPONSE TO MIGRATION AND REFUGEE CRISES IN CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Udoh, Emmanuel Williams, Ph. D Department of Religious and Cultural Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar - Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected]; GSM: 08034038013 Abstract The movement of people from one country to another in search of greener pasture, peaceful settlement and so on, has become very rampant in the world today. These same reasons have triggered internal migrations as well. Lives have been lost in the bid to circumvent immigration laws of countries by immigrants. The current spate of wars, political crises, natural disasters and hunger has led to increase in illegal migration in the world. Nigeria is not left out. We hear of boundary clashes and insurgencies, which have resulted in illegal emigration to other countries basically in search of job opportunities and better living conditions. Nigerians have severally been repatriated from foreign lands. Recently, over five thousand Nigerians were repatriated from Libya. Nigeria has also played host to migrants from neighbouring countries, and has experienced internal migration in several parts of the country. The frequently asked questions are: “what role can religion play in curbing the spate of illegal migration and refugee crises in Cross River State, Nigeria? The research discovered that religion can be a veritable partner to government in resolving this ever-increasing menace that has become an embarrassment to the state and nation. This work adopted qualitative or explorative research method. It employed the content analysis approach in examining available printed materials on the subject matter. -

CROSS RIVER STATE GOVERNMENT in Collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Transportation /Nigerian Ports Authority in Complia

CROSS RIVER STATE GOVERNMENT in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Transportation /Nigerian Ports Authority In compliance with Infrastructure Concession and Regulatory Commission Est. Act 2005 and the National Policy on Public Private Partnership DESIGN, BUILD, FINANCE, OPERATE AND TRANSFER (DBFOT) OF THE BAKASSI INTEGRATED DEEP SEAPORT AND CALABAR–OGOJA–GAKEM SUPERHIGHWAY REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATION 1. The Cross River State Government (CRSG), in collaboration Design Construct and Finance with the Federal Ministry of Transportation and the Nigeria Tolling and Maintenance Ports Authority are desirous of developing the Bakassi Method of Application: Integrated Deep Seaport (on a perimeter area of approximately 12. The qualification documents for interested investors should be structured 36,000 Hectares) under a Public Private Partnership (PPP) into the following sections: arrangement (“Bakassi Deep Seaport Project”) a. Profile of the Firm or Consortium including contact person, postal 2. An integral component of the project is the development of a address, telephone numbers, and e-mail address. If a consortium or 275-km Calabar–Ogoja–Gakem tolled six lane Superhighway joint venture, provide names and contact details of consortium (“Superhighway Project) in the first instance, with the members, evidence of association or joint venture agreement, and possibility for extension to neighboring states in the future. indicate the lead firm in the consortium or joint venture; 3. The purpose of the above-named greenfield projects (‘the b. Ownership structure of bidding entity. Name(s) of major Projects”) is to enhance the national cargo handling capacities shareholders and percentage shareholding of participants in the and serve as logistics corridor for the proposed Bakassi Deep bidding entity; Seaport respectively. -

The ICJ's Decision on Bakassi Peninsula in Retrospect

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 10; October 2016 The ICJ’s Decision on Bakassi Peninsula in Retrospect: a True Evaluation of the History, Issues and Critique of the Judgement E. E. Alobo PhD Senior Lecturer& Former Head of Public and International Law Faculty of Law, University of Calabarand Adjunct Lecturer, Faculty of Law University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria John Adoga Adams, LL.B (Hons), B.L, LL.M, PhD (Cal) Lecturer Faculty of Law University of Calabar-Nigeria S. P. Obaji, LL.B (Hons), B.L, LL.M (Kent) Lecturer, Faculty of Law University of Calabar-Nigeria Abstract Territorial disputes are endemic in Africa; the Bakassi dispute was one of such. It was submitted by Cameroon to the International Court of Justice at The Hague for its determination. The judgement that followed suffered weighty denunciation particularly in Nigeria, yet it enjoyed great approbation internationally. This article takes a magisterial examination of the legal issues raised by the parties and the decision of the court thereto from two angles. First, it analyses the basis of Cameroon’s claim over Bakassi and Nigeria’s responses as formulated by parties. The second part of the article, which affords a critique, focuses on the general and legal grounds upon which the judgment can be faulted. The conclusion that flowed from this analysis is that the ICJ, with due respect, erred in its findings and should be properly guided when forced with similar dispute in future so as to render a valid narrative of International Law Key Words: Judgement on Bakassi, History, Issues and Critique Introduction It is not in dispute that the Bakassi Peninsula is a Nigerian territory by origin. -

The Nigeria-Cameroon Border Conflict Settlement and Matters Arising1

Brazilian Journal of African Studies | Porto Alegre | v.3, n.5, Jan./Jun. 2018 | p. 65-83 65 POST-CONFLICT PEACE-BUILDING IN A CONTESTED INTERNATIONAL BORDER: THE NIGERIA-CAMEROON BORDER CONFLICT SETTLEMENT AND MATTERS ARISING1 Kenneth Chukwuemeka Nwoko2 Introduction The political solution under the Green Tree Agreement which led to the handover of the contested Bakassi Peninsula to Cameroon by Nigeria following the International Court of Justice (2002) ruling signaled the end of the protracted Nigeria/Cameroon border conflict, at least on the surface. However, some analysts believed that it marked the beginning of what may result into a future conflict (Agbakwuru 2012; The Guardian 2006). From the analysis of the verdict of the Court, it would appear that while the interests of the two states involved in the conflict appeared to have been taken into cognizance, the interest of the indigenes and inhabitants of Bakassi was not. Apart from alienating these local people from their ancestral homes, cultural sites and livelihood opportunities, activities such as fishing; interstate water transportation, trading etc, which were operated as early as the pre- colonial days by the local inhabitants, appear to have been disrupted, thus, endangering their means of livelihood and survival. The Anglo-German agreement of March 1913 which the ICJ ruling relied on for its verdict on the Nigeria-Cameroon border conflict represents the earliest milestone in the process of alienation of the inhabitants of the 1 This study was carried out with grants from the African Peacebuilding Network of the Social Science Research Council, USA. 2 Department of History and International Studies, McPherson University, Seriki Sotayo, Nigeria. -

The Role of Natural Resources in Nigeria- Cameroun Border Dispute

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: H Interdisciplinary Volume 18 Issue 5 Version 1.0 Year 2018 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X The Role of Natural Resources in Nigeria- Cameroun Border Dispute By Lucky Igohosa, Ugbudian Alex Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike Abstract- The paper examines the role of natural resources in Nigeria-Cameroun border dispute. Nigerian state administered the areas commonly known as Bakassi peninsula which falls along the borders between Nigeria and Cameroun for decades peacefully. However from 1991 the Cameroun government challenged the rights of Nigeria government over the peninsula which culminated in a suit at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague. Reflecting on archival materials and relevant documents analysed qualitatively using historical approach revealed that the dispute was driven largely by the availability of natural resources such as crude oil and sea products in the peninsula. The contestation of the ownership of the peninsula made the Cameroonians forces to terrorised Nigerians living in the area which drew the intervention of the Nigerian armed forces in a punitive mission to the peninsula and beyond from 198.1 Consequently, the government of Cameroun took the matter to ICJ for adjudication which ruled in favour of Cameroun relying largely on the 11 March 1913 and 29 April 1913Anglo-German colonial boundaries agreements. The paper posited that the contribution that the exploration of huge natural resources including crude oil deposit that the peninsula possess will do to the economy of both countries influenced the violent dimensions the dispute took including the formation of Bakassi Volunteer Force even after the case was taken to the ICJ.