Language and Power in Cross River State, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Constraint-Based Analysis of Obligatory Contour Principle in Anaang Morphological Constructions

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 466-476, May 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1203.17 A Constraint-based Analysis of Obligatory Contour Principle in Anaang Morphological Constructions Unwana Akpabio Department of Linguistics, Igbo and Other Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Olusanmi Babarinde Department of Linguistics, Igbo and Other Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria George Iloene Department of Linguistics, Igbo and Other Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Abstract—The obligatory contour principle forbids identical consecutive features in the underlying representation. This work undertakes a description of the Anaang tonal structure, the tonal behaviour of compounds and reduplicates in the language, bearing in mind their sensitivity to the OCP and the environments that trigger the adherence. An adapted Ibadan wordlist of 400 Basic Items (Trial) English version was used via interview for data collection from six men and six women within Abak Local Government Area in Akwa Ibom State. The data were analysed using optimality theoretical framework. The analysis shows that Anaang compounds as well as reduplicates exhibit cases of tonal modifications in line with OCP. For compounds, the tone of the second noun changes depending on the tonal sequence. In the HH noun base, the second-high tone of the second noun changes to a low tone, in the LH noun base, the tone of the second noun is raised to a down-stepped high tone, the LL noun base sees the tone of the second noun being raised to a high tone. -

Edim Otop Gully Erosion Site in Calabar Municipality, Cross River State

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Public Disclosure Authorized THE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) FOR EDIM OTOP GULLY EROSION SITE IN CALABAR Public Disclosure Authorized MUNICIPALITY, CROSS RIVER STATE Public Disclosure Authorized State Project Management Unit (SPMU) Cross River State, Calabar TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii List of Figures viii List of Plates ix Executive Summary xi CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Description of the Proposed Intervention 3 1.3 Rationale for the Study 5 1.4 Scope of Work 5 CHAPTER TWO - INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK 7 2.1 Background 7 2.2 World Bank Safeguard Policies 8 2.2.1 Environmental Assessment (EA) OP 4.01 9 2.2.2 Natural Habitats (OP 4.04) 9 2.2.3 Pest Management (OP 4.09) 10 2.2.4 Forest (OP 4.36) 10 2.2.5 Physical Cultural Resources (OP 4.11) 11 2.2.6 Involuntary Resettlement (OP 4.12) 11 2.2.7 Safety of Dams OP 4.37 12 2.2.8 Projects on International Waterways OP 7.50 12 2.3 National Policy, Legal, Regulatory and Administrative Frameworks 13 2.3.1 The Federal Ministry of Environment (FMENV) 13 2.3.2 The National Policy on the Environment (NPE) of 1989 14 2.3.3 Environmental Impact Assessment Act No. 86, 1992 (FMEnv) 14 2.3.4 The National Guidelines and Standards for Environmental Pollution Control in Nigeria 14 2.3.5 The National Effluents Limitations Regulation 15 ii 2.3.6 The NEP (Pollution Abatement in Industries and Facilities Generating Waste) Regulations 15 2.3.7 The Management of Solid and Hazardous Wastes Regulations 15 2.3.8 National Guidelines on Environmental Management Systems (1999) 15 2.3.9 National Guidelines for Environmental Audit 15 2.3.10 National Policy on Flood and Erosion Control 2006 (FMEnv) 16 2.3.11 National Air Quality Standard Decree No. -

Human Migratory Pattern: an Appraisal of Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 16 (July. 2017) PP 79-91 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Human Migratory Pattern: An Appraisal of Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria. 1Iheoma Iwuanyanwu, 1Joy Atu (Ph.D.), 1Chukwudi Njoku, 1TonyeOjoko (Arc.), 1Prince-Charles Itu, 2Frank Erhabor 1Department of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria 2Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria Corresponding Author: IheomaIwuanyanwu ABSTRACT: This study assessed migration in Akpabuyo Local Government Area (LGA) of Cross River State, Nigeria. The source regions of migrants in the area were identified; the factors that influence their movements, as well as the remittances of migrants to their source regions were ascertained. A total of 384 copies of questionnaires were systematically administered with a frequency of 230 and 153 samples for migrants and non-migrants respectively. Amongst other findings from the analyses, it was established that Akpabuyo is home to migrants from other LGAs and States, especially BakassiLGA and EbonyiState. There were also migrants from other countries such as Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. The Pearson‟s correlation analysis depicted significant relationship (P = 0.012) between distance to Akpabuyo and the number of migrants that come into the area, implying that distance significantly influences migration to Akpabuyo. Furthermore, the Correspondence Analysis (CA) showed a weak association between the pull and push factors in the area, buttressed by the chi-square testwhich showed insignificant statistical similarity (p = 0.118). It was also established that migrants remitted 74% of their income to their source regions. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

For Multi-Ethnic Harmony in Nigeria

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1974 Curriculum (English language) for multi-ethnic harmony in Nigeria. M. Olu Odusina University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Odusina, M. Olu, "Curriculum (English language) for multi-ethnic harmony in Nigeria." (1974). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2884. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2884 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S/AMHERST 315DbbD13Sfl3DflO CURRICULUM (ENGLISH LANGUAGE) FOR MULTI-ETHNIC HARMONY IN NIGERIA A Dissertation Presented By Margaret Olufunmilayo Odusina Submitted to the graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial degree fulfillment of the requirements for the DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August, 1974 Major Subject: Education ii (C) Margaret Olufunmilayo Odusina 1974 All Rights Reserved iii ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM FOR MULTI-ETHNIC HARMONY IN NIGERIA A Dissertation By Margaret 0. Odusina Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Norma J/an Anderson, Chairman of Committee a iv DEDICATION to My Father: Isaac Adekoya Otunubi Omo Olisa Abata Emi Odo ti m’Odosan Omo• « • * Ola baba ni m’omo yan » • • ' My Mother: Julianah Adepitan Otunubi Omo Oba Ijasi 900 m Ijasi elelemele alagada-m agada Ijasi ni Oluweri ke soggdo My Children: Omobplaji Olufunmilayo T. Odu§ina Odusina Omobolanle Oluf unmike K. • • » • Olufunmilola I. Odusina Omobolape * • A. -

Case Study of Bekwarra Local Government Area, Cross River State

Journal of Public Administration and Governance ISSN 2161-7104 2019, Vol. 9, No. 3 Funding and Implementation of National Programme on Immunization in Nigeria: Case Study of Bekwarra Local Government Area, Cross River State Adie, Hilary Idiege Department of Public Administration, University of Calabar, Calabar-Nigeria Enang, Agnes Ubana Department of Public Administration University of Calabar, Calabar-Nigeria Received: Aug. 9, 2017 Accepted: Jun. 22, 2019 Online published: Jul. 17, 2019 doi:10.5296/jpag.v9i3.15111 URL: https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v9i3.15111 Abstract This study investigated how funding has affected effective implementation of National Programme on Immunization (NPI) in Bekwarra Local Government of Cross River State, Nigeria from 2003-2016. To achieve this objective, a research hypothesis was formulated. A total of 200 Health workers were randomly selected using survey inferential research design from the population of 320 Health workers in the study area. A well validated Likert type scale instrument called Immunization Related Issues Questionnaire (IRIQ) consisting of 22 items with a reliability index of 0.84 was the instrument for data collection. Data collected from the respondents were subjected to the Chi-Suare statistics to test the hypothesis in the study. The result of the test was significant at 0.05 level and it was concluded that funding significantly influences effective implementation of immunization programme in Bekwarra Local Government Area. The study noted that adequate funds are not provided for effective implementation of National Programme on Immunization (NPI), and whenever funds are provided, it is often mismanaged. Also, it was revealed that non-governmental organization (NGOs) should assist in funding immunization programme by providing logistics and technical equipment for effective programme implementation. -

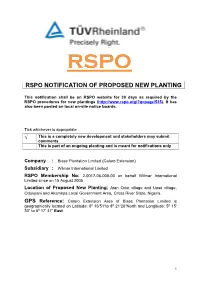

Rspo Notification of Proposed New Planting

RSPO NOTIFICATION OF PROPOSED NEW PLANTING This notification shall be on RSPO website for 30 days as required by the RSPO procedures for new plantings (http://www.rspo.otg/?q=page/535). It has also been posted on local on-site notice boards. Tick whichever is appropriate √ This is a completely new development and stakeholders may submit comments This is part of an ongoing planting and is meant for notifications only Company : Biase Plantation Limited (Calaro Extension) Subsidiary : Wilmar International Limited RSPO Membership No: 2-0017-05-000-00 on behalf Wilmar International Limited since on 15 August 2005 Location of Proposed New Planting: Atan Odot village and Uwet village, Odukpani and Akamkpa Local Government Area, Cross River State, Nigeria. GPS Reference: Calaro Extension Area of Biase Plantation Limited is geographically located on Latitude: 80 16‘51“to 80 21‘26“North and Longitude: 50 15‘ 30“ to 50 17‘ 47“ East. 1 RSPO New Planting Procedure Assessment Report CALARO Extension Estate of Biase Plantation Ltd – Cross River State, Nigeria Location of the Proposed New Planting Total area acquired by Biase Plantation Limited (BPL) according to the MoU between the government of Cross River State of Nigeria and Uwet & Atan Odot Communities / Ikot Eyidok dated on 10 January 2013 and MoU between the landlord communities and Biase Plantation Ltd dated on 10th December 2015 is 3,066.214ha (shown on survey plan no. RIU/CR/191/12). This included potential overlaps with the Uwet-Odot Forest Reserve and the Oban Forest Reserve. Subsequent re-demarcation has excluded the areas of overlap and reduced the total concession area to 2,368.94 Ha (Deed of grant between the government of Cross River State of Nigeria and Biase Plantations Ltd). -

Cassava Farmers' Preferences for Varieties and Seed Dissemination

Cassava farmers’ preferences for varieties and seed dissemination system in Nigeria: Gender and regional perspectives Jeffrey Bentley, Adetunji Olanrewaju, Tessy Madu, Olamide Olaosebikan, Tahirou Abdoulaye, Tesfamichael Wossen, Victor Manyong, Peter Kulakow, Bamikole Ayedun, Makuachukwu Ojide, Gezahegn Girma, Ismail Rabbi, Godwin Asumugha, and Mark Tokula www.iita.org i ii Cassava farmers’ preferences for varieties and seed dissemination system in Nigeria: Gender and regional perspectives J. Bentley, A. Olanrewaju, T. Madu, O. Olaosebikan, T. Abdoulaye, T. Wossen, V. Manyong, P. Kulakow, B. Ayedun, M. Ojide, G. Girma, I. Rabbi, G. Asumugha, and M. Tokula International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan February 2017 IITA Monograph i Published by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) Ibadan, Nigeria. 2017 IITA is a non-profit institution that generates agricultural innovations to meet Africa’s most pressing challenges of hunger, malnutrition, poverty, and natural resource degradation. Working with various partners across sub-Saharan Africa, we improve livelihoods, enhance food and nutrition security, increase employment, and preserve natural resource integrity. It is a member of the CGIAR System Organization, a global research partnership for a food secure future. International address: IITA, Grosvenor House, 125 High Street Croydon CR0 9XP, UK Headquarters: PMB 5320, Oyo Road Ibadan, Oyo State ISBN 978-978-8444-82-4 Correct citation: Bentley, J., A. Olanrewaju, T. Madu, O. Olaosebikan, T. Abdoulaye, T. Wossen, V. Manyong, P. Kulakow, B. Ayedun, M. Ojide, G. Girma, I. Rabbi, G. Asumugha, and M. Tokula. 2017. Cassava farmers’ preferences for varieties and seed dissemination system in Nigeria: Gender and regional perspectives. IITA Monograph, IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria. -

Accessibility of Hiv/Aids Information to Women In

International Journal of Ebola, AIDS, HIV and Infectious Diseases and Immunity Vol.4, No.1, pp.1-11, April 2017 __Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) AVAILABILITY OF HIV/AIDS INFORMATION TO WOMEN IN IKOM LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Felicia U. Iwara CLN Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Library, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: The study was carried out to determine how HIV/AIDS information was made available to women in Ikom Local Government Area. Survey method was used through the administration of questionnaire. 300 copies of the questionnaire were distributed. The return was 90%. It was revealed that, due to poverty and the low level of education, the women found it very difficult to have access to available HIV/AIDS information whenever it was made available. It is therefore, recommended that adult schools should be established in all Local Government Areas of Cross River State especially Ikom Local Government Area to educate the women and sensitize them about the dangers of this deadly disease and how to prevent it especially from mother-child. By educating the women, it will enable them access available HIV/AIDS information at the appropriate time. Women should be empowered so that, they do not rely entirely on men financially. KEYWORDS: Availability, HIV/AIDS, Information, Women, Ikom Local Government, Cross River State INTRODUCTION All over the world HIV/AIDS is causing devastation by its destructive effects on families and economy of the nation. At the end of 2003, a report was issued by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) on the status of HIV/AIDS in the world (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004). -

Print This Article

European Journal of Social Sciences Studies ISSN: 2501-8590 ISSN-L: 2501-8590 Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/soc doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3866894 Volume 5 │ Issue 2 │ 2020 REFUGEE INFLUX: A SOCIOLOGICAL INSIGHT AND EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF ITS CONCOMITANT EFFECT ON FOOD SECURITY IN ETUNG CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Omang, Thomas A.1, Ojong-Ejoh, Mary U.2, Bisong Kenneth B.3, Egom Njin O.4 1&2Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria 3Institute of Public Administration, University of Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria 4Graduate Student, University of Abuja, Nigeria Abstract: The study examines the impact of Cameroun refugee influx and its impact on food security in Etung Local Government Area of Cross River State, Nigeria. The study adopted the survey research method in eliciting information from 400 samples from two political wards in Etung Local Government Area of Cross River State, Nigeria, using the purposive and random sampling technique. a self-administered structured questionnaire was the instrument of Data collection. Data gathered from the field was meticulously collated, coded and analyzed using simple percentages, frequency distribution, figures and simple lineal regression at 0.05 confidence level. Result revealed that there is a significant relationship between refugee influx and Food Security in Etung Local Government Area of Cross River State, Nigeria. The study recommends That the Cross- River state synergizes with the relevant agencies of the Federal Government as well as other international Agencies to stimulate production in Etung through agricultural programs such as farmers smallholders schemes, cassava, banana, yam, plantain plantations schemes, animal husbandry, cottage industries etc. -

Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT

Report of the Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV March 2013 Report of the Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV May 2013 This publication may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced, or translated, in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. The mention of specific organizations does not imply endorsement and does not suggest that they are recommended by the Cross River State Ministry of Health over others of a similar nature not mentioned. Copyright © 2013 Cross River State Ministry of Health, Nigeria Citation: Cross River State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. 2013. Cross River State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment, Nigeria: Cross River State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. The Cross River State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment was supported in part by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). FHI 360 provided assistance to the Cross River State Government to conduct this assessment. Financial assistance was provided by USAID under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-620-A-00002, of the Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/ AIDS Services Project. This report does not necessarily reflect the views of FHI 360, USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Relic Noun-Class Structure in Leggbo

6 RELIC NOUN-CLASS STRUCTURE IN LEGGBO Larry M. Hyman and Imelda Udoh 1. Introduction * In many West African Niger-Congo languages, historical noun class prefixes undergo significant levelling and/or fusion with the noun stem. Starting from a full set of singular-plural markers both on nouns and on agreeing elements, the logical endpoint of such changes can be the total loss of noun classes, as has happened some of the best-known Benue-Congo and Kwa languages, e.g., Akan, Ewe, Yoruba, Igbo. Resistance to this tendency can be found in certain subgroups in Nigeria, e.g., Upper Cross, where languages such as Mbembe (Barnwell 1969a,b), and Lokaa (lwara 1982) have been reported to have full-fledged noun class marking and concord systems. It is thus striking that closely related Leggbo has lost all noun class agreement. Still, it is possible to identify a prefix-stem structure on the basis of a number of arguments. The purpose of this paper is to document relic noun-class structures in Leggbo, an Upper Cross minority language. Leggbo is spoken by an estimated 60,000 Agbo people in two local government areas, recently named Abi and YakuIT, in Cross River State. In §2 and §3 we demonstrate that although Leggbo has lost the inherited noun class system, nouns must still be analyzed as consisting of a prefix-stem structure. Sections §4 and §5 provide further evidence from reduplication and compounding, respectively, and §6 illustrates relics of • The present study is based on a field methods course held at the University of California, Berkeley during the academic year 2001-02, with the second author serving as consultant.