Calabar Municipal Recreation Centre Expression Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edim Otop Gully Erosion Site in Calabar Municipality, Cross River State

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Public Disclosure Authorized THE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) FOR EDIM OTOP GULLY EROSION SITE IN CALABAR Public Disclosure Authorized MUNICIPALITY, CROSS RIVER STATE Public Disclosure Authorized State Project Management Unit (SPMU) Cross River State, Calabar TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii List of Figures viii List of Plates ix Executive Summary xi CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Description of the Proposed Intervention 3 1.3 Rationale for the Study 5 1.4 Scope of Work 5 CHAPTER TWO - INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK 7 2.1 Background 7 2.2 World Bank Safeguard Policies 8 2.2.1 Environmental Assessment (EA) OP 4.01 9 2.2.2 Natural Habitats (OP 4.04) 9 2.2.3 Pest Management (OP 4.09) 10 2.2.4 Forest (OP 4.36) 10 2.2.5 Physical Cultural Resources (OP 4.11) 11 2.2.6 Involuntary Resettlement (OP 4.12) 11 2.2.7 Safety of Dams OP 4.37 12 2.2.8 Projects on International Waterways OP 7.50 12 2.3 National Policy, Legal, Regulatory and Administrative Frameworks 13 2.3.1 The Federal Ministry of Environment (FMENV) 13 2.3.2 The National Policy on the Environment (NPE) of 1989 14 2.3.3 Environmental Impact Assessment Act No. 86, 1992 (FMEnv) 14 2.3.4 The National Guidelines and Standards for Environmental Pollution Control in Nigeria 14 2.3.5 The National Effluents Limitations Regulation 15 ii 2.3.6 The NEP (Pollution Abatement in Industries and Facilities Generating Waste) Regulations 15 2.3.7 The Management of Solid and Hazardous Wastes Regulations 15 2.3.8 National Guidelines on Environmental Management Systems (1999) 15 2.3.9 National Guidelines for Environmental Audit 15 2.3.10 National Policy on Flood and Erosion Control 2006 (FMEnv) 16 2.3.11 National Air Quality Standard Decree No. -

Human Migratory Pattern: an Appraisal of Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 16 (July. 2017) PP 79-91 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Human Migratory Pattern: An Appraisal of Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria. 1Iheoma Iwuanyanwu, 1Joy Atu (Ph.D.), 1Chukwudi Njoku, 1TonyeOjoko (Arc.), 1Prince-Charles Itu, 2Frank Erhabor 1Department of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria 2Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria Corresponding Author: IheomaIwuanyanwu ABSTRACT: This study assessed migration in Akpabuyo Local Government Area (LGA) of Cross River State, Nigeria. The source regions of migrants in the area were identified; the factors that influence their movements, as well as the remittances of migrants to their source regions were ascertained. A total of 384 copies of questionnaires were systematically administered with a frequency of 230 and 153 samples for migrants and non-migrants respectively. Amongst other findings from the analyses, it was established that Akpabuyo is home to migrants from other LGAs and States, especially BakassiLGA and EbonyiState. There were also migrants from other countries such as Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. The Pearson‟s correlation analysis depicted significant relationship (P = 0.012) between distance to Akpabuyo and the number of migrants that come into the area, implying that distance significantly influences migration to Akpabuyo. Furthermore, the Correspondence Analysis (CA) showed a weak association between the pull and push factors in the area, buttressed by the chi-square testwhich showed insignificant statistical similarity (p = 0.118). It was also established that migrants remitted 74% of their income to their source regions. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Fear and Faith: Uncertainty, Misfortune and Spiritual Insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Ligtvoet, I.J.G.C

Fear and faith: uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Ligtvoet, I.J.G.C. Citation Ligtvoet, I. J. G. C. (2011). Fear and faith: uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria. s.l.: s.n. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22696 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/22696 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Fear and Faith Uncertainty, misfortune and spiritual insecurity in Calabar, Nigeria Inge Ligtvoet MA Thesis Supervision: ResMA African Studies Dr. Benjamin Soares Leiden University Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn August 2011 Dr. Oka Obono Dedicated to Reinout Lever † Hoe kan de Afrikaanse zon jouw lichaam nog verwarmen en hoe koelt haar regen je af na een tropische dag? Hoe kan het rode zand jouw voeten nog omarmen als jij niet meer op deze wereld leven mag? 1 Acknowledgements From the exciting social journey in Nigeria that marked the first part of this work to the long and rather lonely path of the final months of writing, many people have challenged, advised, heard and answered me. I have to thank you all! First of all I want to thank Dr. Benjamin Soares, for being the first to believe in my fieldwork plans in Nigeria and for giving me the opportunity to explore this fascinating country. His advice and comments in the final months of the writing have been really encouraging. I’m also grateful for the supervision of Prof. Mirjam de Bruijn. From the moment she got involved in this project she inspired me with her enthusiasm and challenged me with critical questions. -

Accessibility of Hiv/Aids Information to Women In

International Journal of Ebola, AIDS, HIV and Infectious Diseases and Immunity Vol.4, No.1, pp.1-11, April 2017 __Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) AVAILABILITY OF HIV/AIDS INFORMATION TO WOMEN IN IKOM LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Felicia U. Iwara CLN Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Library, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: The study was carried out to determine how HIV/AIDS information was made available to women in Ikom Local Government Area. Survey method was used through the administration of questionnaire. 300 copies of the questionnaire were distributed. The return was 90%. It was revealed that, due to poverty and the low level of education, the women found it very difficult to have access to available HIV/AIDS information whenever it was made available. It is therefore, recommended that adult schools should be established in all Local Government Areas of Cross River State especially Ikom Local Government Area to educate the women and sensitize them about the dangers of this deadly disease and how to prevent it especially from mother-child. By educating the women, it will enable them access available HIV/AIDS information at the appropriate time. Women should be empowered so that, they do not rely entirely on men financially. KEYWORDS: Availability, HIV/AIDS, Information, Women, Ikom Local Government, Cross River State INTRODUCTION All over the world HIV/AIDS is causing devastation by its destructive effects on families and economy of the nation. At the end of 2003, a report was issued by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) on the status of HIV/AIDS in the world (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004). -

Resource Allocation and the Problem of Utilization in Nigeria: an Analysis of Resource Utilization in Cross River State, 1999-2007

Resource Allocation and the Problem of Utilization in Nigeria: An Analysis of Resource Utilization in Cross River State, 1999-2007 By ATELHE, GEORGE ATELHE Ph. D/SOC-SCI/02799/2006-2007 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST- GRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE. JANUARY, 2013 1 DEDICATION This research is dedicated to the Almighty God for His faithfulness and mercy. And to all my teachers who have made me what I am. 2 DELARATION I, Atelhe George Atelhe hereby declare, that this Dissertation has been prepared and written by me and it is the product of my own research. It has not been accepted for any degree elsewhere. All quotations have been indicated by quotation marks or by indentation and acknowledged by means of bibliography. __________________ ____________ Atelhe, George Atelhe Signature/Date 3 CERTIFICATION This Dissertation titled ‘Resource Allocation and the Problem of Utilization in Nigeria: An Analysis of Resource Utilization in Cross River State, 1999-2007’ meets the regulation governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) of Ahmadu Bello University, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. ____________________________ ________________ Dr. Kayode Omojuwa Date Chairman, Supervisory Committee ____________________________ ________________ Dr. Umar Mohammed Kao’je Date Member, Supervisory Committee ___________________________ ________________ Prof. R. Ayo Dunmoye Date Member, Supervisory Committee ___________________________ ________________ Dr. Hudu Abdullahi Ayuba Date Head of Department ___________________________ ________________ Dean, School of Post-Graduate Studies Date 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Words are indeed inadequate to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors, Dr Kayode Omojuwa, Dr Umar Kao’je, and Prof R.A. -

Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT

Report of the Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV March 2013 Report of the Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV May 2013 This publication may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced, or translated, in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. The mention of specific organizations does not imply endorsement and does not suggest that they are recommended by the Cross River State Ministry of Health over others of a similar nature not mentioned. Copyright © 2013 Cross River State Ministry of Health, Nigeria Citation: Cross River State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. 2013. Cross River State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment, Nigeria: Cross River State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. The Cross River State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment was supported in part by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). FHI 360 provided assistance to the Cross River State Government to conduct this assessment. Financial assistance was provided by USAID under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-620-A-00002, of the Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/ AIDS Services Project. This report does not necessarily reflect the views of FHI 360, USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Nigeria - Accessibility to Emonc Facilities in the State of Cross River

Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities in the State of Cross River Last Update: March 2016 Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities for the Cross River State Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Measured indicators and assumptions .................................................................................... 5 3. Tool used for the different analyses: AccessMod 5.0 ............................................................. 7 4. Data and national norms used in the different analyses .......................................................... 8 4.1 Statistical Data ............................................................................................................... 9 4.1.1 LGA Number of pregnant women for 2010 and 2015 ........................................... 9 4.2 Geospatial Data ........................................................................................................... 12 4.2.1 Administrative boundaries and extent of the study area ...................................... 13 4.2.2 Geographic location of the EmONC facilities and associated information ......... 17 4.2.4 Transportation network ........................................................................................ 26 4.2.5 Hydrographic network ........................................................................................ -

Carnival Fiesta and Socio-Economic Development of Calabar Metropolis, Nigeria F

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 2 Issue 6 ǁ June. 2013ǁ PP.33-41 Carnival Fiesta and Socio-economic development of Calabar Metropolis, Nigeria F. M. Attah1, Agba, A. M. Ogaboh2 and Festus Nkpoyen3 1Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. 2(corresponding author) is also a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. 3Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: Purpose- This study examines the relationship between Calabar carnival fiesta and the socio- economic development of Calabar metropolis in Cross River State, Nigeria. Design/methodology/approach- The approach adopted in this study was survey method which employed structured questionnaires,which were administered to 1495 respondents. Data elicited from respondents were analyzed using simple percentage and Pearson product moment correlation. Findings - The study reveals that Calabar carnival fiesta significantly influence the development of infrastructural facilities, level of poverty, standard of living of the people in terms of clean and healthy environment and the sexual behaviour of the people in Calabar Metropolis. Practical implications –Some of the recommendations are, that, a blue print on Calabar carnival fiesta be expanded to include other parts of Cross River State. Originality/value- This research work is the first empirical work to assess the impact of Calabar carnival fiesta on the socio-economic development of Calabar Metropolis. Empirical evidence from the field provides an insight that could assist in redesigning tourism blue print in Cross River State. -

Cross River State

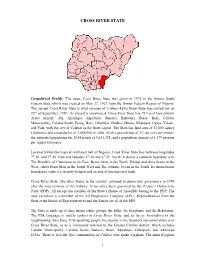

CROSS RIVER STATE Geopolitical Profile: The name Cross River State was given in 1976 to the former South Eastern State which was created on May 27, 1967 from the former Eastern Region of Nigeria. The current Cross River State is what remains of it when Akwa Ibom State was carved out on 23rd of September, 1987. As presently constituted, Cross River State has 18 Local Government Areas namely; Abi, Akamkpa, Akpabuyo, Bakassi, Bekwarra, Biase, Boki, Calabar Municipality, Calabar South, Etung, Ikom, Obanliku, Obubra, Obudu, Odukpani, Ogoja, Yakurr, and Yala; with the city of Calabar as the State capital. The State has land area of 23,000 square kilometres and a population of 2,888,966 in 2006. With a growth rate of 2.9 per cent per annum, the estimated population for 2014 stands at 3,631,328, and a population density of 1,579 persons per square kilometre. Located within the tropical rainforest belt of Nigeria, Cross River State lies between longitudes 7⁰ 50’ and 9⁰ 28’ East and latitudes 4⁰ 28’and 6⁰ 55’ North. It shares a common boundary with The Republic of Cameroun in the East, Benue State in the North, Ebonyi and Abia States in the West, Akwa Ibom State in the South West and The Atlantic Ocean in the South. Its international boundaries make it a security hotspot and an axis of international trade. Cross River State, like other States in the country, returned to democratic governance in 1999 after the interventions of the military. It has since been governed by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). -

NIGERIA: Registration of Cameroonian Refugees September 2019

NIGERIA: Registration of Cameroonian Refugees September 2019 TARABA KOGI BENUE TAKUM 1,626 KURMI NIGERIA 570 USSA 201 3,180 6,598 SARDAUNA KWANDE BEKWARA YALA DONGA-MANTUNG MENCHUM OBUDU OBANLIKU ENUGU 2,867 OGOJA AKWAYA 17,301 EBONYI BOKI IKOM 1,178 MAJORITY OF THE ANAMBRA REFUGEES ORIGINATED OBUBRA FROM AKWAYA 44,247 ABI Refugee Settlements TOTAL REGISTERED YAKURR 1,295ETUNG MANYU REFUGEES FROM IMO CAMEROON CROSS RIVER ABIA BIOMETRICALLY BIASE VERIFIED 35,636 3,533 AKAMKPA CAMEROON Refugee Settlements ODUKPANI 48 Registration Site CALABAR 1,058MUNICIPAL UNHCR Field Office AKWA IBOM CALABAR NDIAN SOUTH BAKASSI667 UNHCR Sub Office 131 58 AKPABUYO RIVERS Affected Locations 230 Scale 1:2,500,000 010 20 40 60 80 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official Kilometers endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Data Source: UNHCR Creation Date: 2nd October 2019 DISCLAIMER: The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. A technical team has been conducting a thorough review of the information gathered so as to filter out any data discrepancies. BIOMETRICALLY VERIFIED REFUGEES REGISTRATION TREND PER MONTH 80.5% (35,636 individuals) of the total refugees 6272 counteded at household level has been 5023 registered/verified through biometric capture of iris, 4025 3397 fingerprints and photo. Refugee information were 2909 2683 2371 also validated through amendment of their existing 80.5% information, litigation and support of national 1627 1420 1513 1583 586 VERIFIED documentations. Provision of Refugee ID cards will 107 ensure that credible information will effectively and efficiently provide protection to refugees. -

Conflict Incident Monthly Tracker

Conflict Incident Monthly Tracker Cross River State: February - M a rch 20 1 8 B a ck gro und Municipal. Others: In February, Cameroonian Criminality was a driver of Violence Affecting gendarmes reportedly killed three fishermen This monthly tracker is designed to update Women and Girls (VAWG) in the state during and injured two others in a border Peace Agents on patterns and trends in the period. In January, for instance, a female community in Ikom LGA. The incident conflict risk and violence, as identified by the medical doctor was abducted in Calabar happened while the gendarmes were in Integrated Peace and Development Unit Municipal. Separately, in January, a female pursuit of separatists agitating for (IPDU) early warning system, and to seek medical doctor was kidnapped in Akamkpa Ambazonia Republic in Southern Cameroon. feedback and input for response to mitigate LGA. areas of conflict. Gang/Cult Violence: In January, four people Recent Incidents or Patterns and Trends were reportedly killed during a rival cult Issues, March 2018 D ec 2 01 7 -Fe b 20 1 8 clash between Bendeghe Mafia and another local cult group in Boki LGA. A policeman Incidents reported during the month related According to Peace Map data (see Figure 1), was reportedly injured during a shootout mainly to communal tensions, criminality, incidents reported during this period with the cultists. Separately, a man was and cult violence. included communal violence, criminality, reportedly shot dead by members of a cult Communal Tensions: Eight people were militancy, cult violence, and child trafficking. group, known as the King Crackers during a reportedly killed during a clash over a land Communal Violence: In February, a political assembly in Calabar South LGA.