THE RELIGIOUS RESPONSE to MIGRATION and REFUGEE CRISES in CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Udoh, Emmanuel Williams, Ph. D Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Migratory Pattern: an Appraisal of Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 16 (July. 2017) PP 79-91 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Human Migratory Pattern: An Appraisal of Akpabuyo, Cross River State, Nigeria. 1Iheoma Iwuanyanwu, 1Joy Atu (Ph.D.), 1Chukwudi Njoku, 1TonyeOjoko (Arc.), 1Prince-Charles Itu, 2Frank Erhabor 1Department of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria 2Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria Corresponding Author: IheomaIwuanyanwu ABSTRACT: This study assessed migration in Akpabuyo Local Government Area (LGA) of Cross River State, Nigeria. The source regions of migrants in the area were identified; the factors that influence their movements, as well as the remittances of migrants to their source regions were ascertained. A total of 384 copies of questionnaires were systematically administered with a frequency of 230 and 153 samples for migrants and non-migrants respectively. Amongst other findings from the analyses, it was established that Akpabuyo is home to migrants from other LGAs and States, especially BakassiLGA and EbonyiState. There were also migrants from other countries such as Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. The Pearson‟s correlation analysis depicted significant relationship (P = 0.012) between distance to Akpabuyo and the number of migrants that come into the area, implying that distance significantly influences migration to Akpabuyo. Furthermore, the Correspondence Analysis (CA) showed a weak association between the pull and push factors in the area, buttressed by the chi-square testwhich showed insignificant statistical similarity (p = 0.118). It was also established that migrants remitted 74% of their income to their source regions. -

Case Study of Bekwarra Local Government Area, Cross River State

Journal of Public Administration and Governance ISSN 2161-7104 2019, Vol. 9, No. 3 Funding and Implementation of National Programme on Immunization in Nigeria: Case Study of Bekwarra Local Government Area, Cross River State Adie, Hilary Idiege Department of Public Administration, University of Calabar, Calabar-Nigeria Enang, Agnes Ubana Department of Public Administration University of Calabar, Calabar-Nigeria Received: Aug. 9, 2017 Accepted: Jun. 22, 2019 Online published: Jul. 17, 2019 doi:10.5296/jpag.v9i3.15111 URL: https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v9i3.15111 Abstract This study investigated how funding has affected effective implementation of National Programme on Immunization (NPI) in Bekwarra Local Government of Cross River State, Nigeria from 2003-2016. To achieve this objective, a research hypothesis was formulated. A total of 200 Health workers were randomly selected using survey inferential research design from the population of 320 Health workers in the study area. A well validated Likert type scale instrument called Immunization Related Issues Questionnaire (IRIQ) consisting of 22 items with a reliability index of 0.84 was the instrument for data collection. Data collected from the respondents were subjected to the Chi-Suare statistics to test the hypothesis in the study. The result of the test was significant at 0.05 level and it was concluded that funding significantly influences effective implementation of immunization programme in Bekwarra Local Government Area. The study noted that adequate funds are not provided for effective implementation of National Programme on Immunization (NPI), and whenever funds are provided, it is often mismanaged. Also, it was revealed that non-governmental organization (NGOs) should assist in funding immunization programme by providing logistics and technical equipment for effective programme implementation. -

Little Genetic Differentiation As Assessed by Uniparental Markers in the Presence of Substantial Language Variation in Peoples O

Veeramah et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2010, 10:92 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/92 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Little genetic differentiation as assessed by uniparental markers in the presence of substantial language variation in peoples of the Cross River region of Nigeria Krishna R Veeramah1,2*, Bruce A Connell3, Naser Ansari Pour4, Adam Powell5, Christopher A Plaster4, David Zeitlyn6, Nancy R Mendell7, Michael E Weale8, Neil Bradman4, Mark G Thomas5,9,10 Abstract Background: The Cross River region in Nigeria is an extremely diverse area linguistically with over 60 distinct languages still spoken today. It is also a region of great historical importance, being a) adjacent to the likely homeland from which Bantu-speaking people migrated across most of sub-Saharan Africa 3000-5000 years ago and b) the location of Calabar, one of the largest centres during the Atlantic slave trade. Over 1000 DNA samples from 24 clans representing speakers of the six most prominent languages in the region were collected and typed for Y-chromosome (SNPs and microsatellites) and mtDNA markers (Hypervariable Segment 1) in order to examine whether there has been substantial gene flow between groups speaking different languages in the region. In addition the Cross River region was analysed in the context of a larger geographical scale by comparison to bordering Igbo speaking groups as well as neighbouring Cameroon populations and more distant Ghanaian communities. Results: The Cross River region was shown to be extremely homogenous for both Y-chromosome and mtDNA markers with language spoken having no noticeable effect on the genetic structure of the region, consistent with estimates of inter-language gene flow of 10% per generation based on sociological data. -

The Relevance of Tourism on the Economic Development of Cross River State, Nigeria

Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Vol. 5(1), pp. 14-20, 4 January, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP DOI: 10.5897/JGRP11.122 ISSN 2070-1845 ©2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper The relevance of tourism on the economic development of Cross River State, Nigeria Ajake, Anim O. and Amalu, Titus E.* Department of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. Accepted 21 December, 2011 This study investigated the relevance of tourism on the economic growth of Cross River State, Nigeria. Special focus was on the difference in visitations over the years under investigation to the various tourists attractions within the state. Information for the study was basically from the questionnaire survey and participatory research method. The generated data were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as mean, simple percentages and graphic illustrations. The study demonstrated that there was a steady increase in the number of tourists visit to the various attraction sites in the area and that the greatest increase was observed in the number of tourists visiting for the purpose of cultural festivals. The result show that tourism influenced employment status, including enhancement of the people’s income in the state. Based on the aforementioned findings, it is recommended that all stakeholders in the tourism industry should be involved in the planning and execution of tourism projects and that tourism activities be organized all through the year to ensure more tourists visitation and avoid seasonality in the tourism industry. Key words: Tourism, influence, cultural enhancement, economic growth, cultural diversity. INTRODUCTION The substantial growth of the tourism activity clearly nearly 30%. -

Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT

Report of the Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV March 2013 Report of the Cross River STATE-WIDE RAPID HEALTH FACILITY ASSESSMENT In Preparation for Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV May 2013 This publication may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced, or translated, in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. The mention of specific organizations does not imply endorsement and does not suggest that they are recommended by the Cross River State Ministry of Health over others of a similar nature not mentioned. Copyright © 2013 Cross River State Ministry of Health, Nigeria Citation: Cross River State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. 2013. Cross River State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment, Nigeria: Cross River State Ministry of Health and FHI 360. The Cross River State-wide Rapid Health Facility Assessment was supported in part by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). FHI 360 provided assistance to the Cross River State Government to conduct this assessment. Financial assistance was provided by USAID under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-620-A-00002, of the Strengthening Integrated Delivery of HIV/ AIDS Services Project. This report does not necessarily reflect the views of FHI 360, USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Nigeria - Accessibility to Emonc Facilities in the State of Cross River

Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities in the State of Cross River Last Update: March 2016 Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities for the Cross River State Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Measured indicators and assumptions .................................................................................... 5 3. Tool used for the different analyses: AccessMod 5.0 ............................................................. 7 4. Data and national norms used in the different analyses .......................................................... 8 4.1 Statistical Data ............................................................................................................... 9 4.1.1 LGA Number of pregnant women for 2010 and 2015 ........................................... 9 4.2 Geospatial Data ........................................................................................................... 12 4.2.1 Administrative boundaries and extent of the study area ...................................... 13 4.2.2 Geographic location of the EmONC facilities and associated information ......... 17 4.2.4 Transportation network ........................................................................................ 26 4.2.5 Hydrographic network ........................................................................................ -

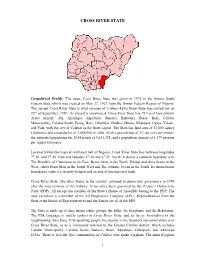

Cross River State

CROSS RIVER STATE Geopolitical Profile: The name Cross River State was given in 1976 to the former South Eastern State which was created on May 27, 1967 from the former Eastern Region of Nigeria. The current Cross River State is what remains of it when Akwa Ibom State was carved out on 23rd of September, 1987. As presently constituted, Cross River State has 18 Local Government Areas namely; Abi, Akamkpa, Akpabuyo, Bakassi, Bekwarra, Biase, Boki, Calabar Municipality, Calabar South, Etung, Ikom, Obanliku, Obubra, Obudu, Odukpani, Ogoja, Yakurr, and Yala; with the city of Calabar as the State capital. The State has land area of 23,000 square kilometres and a population of 2,888,966 in 2006. With a growth rate of 2.9 per cent per annum, the estimated population for 2014 stands at 3,631,328, and a population density of 1,579 persons per square kilometre. Located within the tropical rainforest belt of Nigeria, Cross River State lies between longitudes 7⁰ 50’ and 9⁰ 28’ East and latitudes 4⁰ 28’and 6⁰ 55’ North. It shares a common boundary with The Republic of Cameroun in the East, Benue State in the North, Ebonyi and Abia States in the West, Akwa Ibom State in the South West and The Atlantic Ocean in the South. Its international boundaries make it a security hotspot and an axis of international trade. Cross River State, like other States in the country, returned to democratic governance in 1999 after the interventions of the military. It has since been governed by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). -

NIGERIA: Registration of Cameroonian Refugees September 2019

NIGERIA: Registration of Cameroonian Refugees September 2019 TARABA KOGI BENUE TAKUM 1,626 KURMI NIGERIA 570 USSA 201 3,180 6,598 SARDAUNA KWANDE BEKWARA YALA DONGA-MANTUNG MENCHUM OBUDU OBANLIKU ENUGU 2,867 OGOJA AKWAYA 17,301 EBONYI BOKI IKOM 1,178 MAJORITY OF THE ANAMBRA REFUGEES ORIGINATED OBUBRA FROM AKWAYA 44,247 ABI Refugee Settlements TOTAL REGISTERED YAKURR 1,295ETUNG MANYU REFUGEES FROM IMO CAMEROON CROSS RIVER ABIA BIOMETRICALLY BIASE VERIFIED 35,636 3,533 AKAMKPA CAMEROON Refugee Settlements ODUKPANI 48 Registration Site CALABAR 1,058MUNICIPAL UNHCR Field Office AKWA IBOM CALABAR NDIAN SOUTH BAKASSI667 UNHCR Sub Office 131 58 AKPABUYO RIVERS Affected Locations 230 Scale 1:2,500,000 010 20 40 60 80 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official Kilometers endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Data Source: UNHCR Creation Date: 2nd October 2019 DISCLAIMER: The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. A technical team has been conducting a thorough review of the information gathered so as to filter out any data discrepancies. BIOMETRICALLY VERIFIED REFUGEES REGISTRATION TREND PER MONTH 80.5% (35,636 individuals) of the total refugees 6272 counteded at household level has been 5023 registered/verified through biometric capture of iris, 4025 3397 fingerprints and photo. Refugee information were 2909 2683 2371 also validated through amendment of their existing 80.5% information, litigation and support of national 1627 1420 1513 1583 586 VERIFIED documentations. Provision of Refugee ID cards will 107 ensure that credible information will effectively and efficiently provide protection to refugees. -

The Cross River Super Highway: Fact Sheet

The Cross River Super Highway: Fact Sheet TIMELINE After May 2015: Super highway construction announced severally by Governor FOREST ASSETS Ayade, together with the installation of a deep sea port in the mangroves. Cross River State is host to the largest remaining rainforests of Nigeria. September 2015: Groundbreaking ceremony and visit by President Buhari The Cross River National Park has two distinct, non-contiguous divisions: Oban postponed because of non-existing Environmental Impact Assessment. Re-routing and Okwangwo, with a total area of about 4,000 square km. Protected forests of highway to move it outside the National Park. also exist outside the boundaries of the National Park. In total, Cross River 20 October 2015: Buhari performs the groundbreaking ceremony at Obong State hosts at least 5,524 sq km of protected rainforests. Akamkpa LGA, Cross Rivers State. One of the highest bio-diversity forests in the world, Cross River State is home 22 January 2016: Cross River Government Gazette announces revocation of all to highly threatened species including Cross River gorilla, Nigeria-Cameroon occupancy titles within a 20 kilometre wide corridor of land along the highway chimpanzee, drill monkeys and many others, and hosts about 1,568 plant route. species, of which 77 are endangered including medicinal plants and orchids. February, 2016: Bulldozers enter the Ekuri-Eyeyeng, Etara and Okuni areas and Two new species of orchids were found to be unique to Cross River forests: start clearing and felling of trees. Communities in Old and New Ekuri prevent Tridactyle sp nov. and Hebenaria sp nov. bulldozers from logging in their forest. -

Anti-Bullet Charms, Lie-Detectors and Street Justice: the Nigerian Youth and the Ambiguities of Self-Remaking

At the International Conference, Youth and the Global South: Dakar, Senegal, 13 - 15 October 2006. Anti-Bullet Charms, Lie-Detectors and Street Justice: the Nigerian Youth and the Ambiguities of Self-Remaking Babson Ajibade Cross River University of Technology, Calabar, Nigeria. Abstract The failure of the Nigerian state, its police and judiciary to provide security has eroded citizenship trust. But this failure has tended to implicate the so-called ‘elders’ normally in charge of village, township and urban life-worlds. Disappointedly, Nigeria’s ‘young generations’ creatively assume unofficial yet central positions of ambiguity in the restoration of social order and security. In urban, peri-urban and rural locations ethnic militias and private youth gangs operate as alternative police and adjunct judiciary in place of the state’s failed institutions. These militia and youth gangs use guns, charms and violence to contest pressing concerns and negotiate contemporary realities. While processes of political economy and globalization remain unfavourable, youths – as agents and subjects of social change – are able to subvert status quo by deploying materials appropriated from the local and the global to define ambiguous positions. In one such hybridised situation, youths in Obudu1 have created a device they term ‘lie-detector’ – by fusing ideas gleaned from local and global media spaces. Using this device as central but unconventional social equipment and, drawing validation from traditional social systems, these youths are negotiating new selves in a contemporary milieu. Using the analysis of social practice and popular representation of youth roles, activities and initiatives in Nigeria, this paper shows how sociality and its contestation in urban life moves the Nigerian youth from the periphery to the centre of social, political and economic nationalisms. -

Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Agwagune

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (3), Serial No. 30, July, 2013:261-279 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v7i3.19 Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Agwagune Ugot, Mercy - Centre for General Studies, Cross River University of Technology, Calabar, Nigeria Tel: +234 803 710 2294 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper focuses on the Agwagune language, which belongs to the Niger- Congo phylum and is spoken in Biase local government area of Cross River State, Nigeria. The language has been classified as a minority language because of its paucity in development and demography. The paper examines the phenomenon of lexical enrichment in the language which has been brought about by contact with other languages and the need to develop new vocabulary to cope with new concepts. Such has been achieved through borrowing from other language sources, compounding, hybridization, collocation and so on. Language contact has also led to the phenomena of code-switching and code-mixing. Data for this work was obtained primarily through direct interactions with native speakers and from secondary sources. The language still needs to develop a corpus for the language of technology. Key Words: Code-mixing, collocation, hybridization, metaphorical extensions, superstrate languages. Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 261 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (3) Serial No. 30, July, 2013 Pp.261-279 Introduction Thomason, (1991) views language contacts as something that has existed for a very long time, probably since the beginning of mankind. Language contact has been shown to have far-reaching social, political, and linguistic effects. -

Evaluation of Intensity of Urinary Schistosomiasis in Biase and Yakurr Local Government Areas of Cross River State, Nigeria Afte

Research Journal of Parasitology 10 (2): 58-65, 2015 ISSN 1816-4943 / DOI: 10.3923/jp.2015.58.65 © 2015 Academic Journals Inc. Evaluation of Intensity of Urinary Schistosomiasis in Biase and Yakurr Local Government Areas of Cross River State, Nigeria after Two Years of Integrated Control Measures 1H.A. Adie, 1A. Oyo-Ita, 2O.E. Okon, 2G.A. Arong, 3I.A. Atting, 4E.I. Braide, 5O. Nebe, 6U.E. Emanghe and 7A.A. Otu 1Ministry of Health, Calabar, Nigeria 2Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, University of Calabar, Nigeria 3Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, University of Uyo/University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria 4Federal University, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria 5Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria 6Department of Medical Microbiology/Parasitology, University of Calabar, Nigeria 7Department of Internal Medicine, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria Corresponding Author: H.A. Adie, Ministry of Health, Calabar, Nigeria ABSTRACT A parasitological mapping of urinary schistosomiasis using filtration method was conducted in Biase and Yakurr LGAs of Cross River State, Nigeria by the Neglected Tropical Diseases Control unit in collaboration with the schistosomiasis/soil transmitted helminths unit of the Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria in November 2012. The results of the study revealed a mean urinary schistosomiasis prevalence of 49% for the six schools under study in Biase and 30% for the six schools under study in Yakurr LGA. The mean ova load was 0.9 for males and 0.8 for females in the two LGAs. Integrated control measures put in place, included chemotherapy of infected individuals with praziquantel and health education on the predisposing factors responsible for the transmission of urinary schistosomiasis.