Nicholas Gray – University College London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

Transmissions of Trauma in Junot Díaz's the Brief

PÁGINAS EN BLANCO : TRANSMISSIONS OF TRAUMA IN JUNOT DÍAZ’S THE BRIEF WONDROUS LIFE OF OSCAR WAO Catalina Rivera A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: María DeGuzmán Ruth Salvaggio © 2011 Catalina Rivera ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CATALINA RIVERA: Páginas en blanco: Transmissions of Trauma in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Under the direction of María DeGuzmán) While the titular character of Oscar appears to be unequivocal hero of Junot Díaz’s novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the narrating figure of Yunior drives the text with his plural role as Watcher, teller, and participant in the drama of Oscar’s tragedy. His footnotes, which often perplex readers by their very presence in a work of fiction, allow Yunior an intimate space in which he may bring language to the enigmatic truths of his trauma as a subject who subconsciously carries the burden of Dominican history; an impossible past wrought by Spanish conquest, the slave trade and the consequent economy of breeding people, the U.S. backed dictatorship of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina in the Dominican Republic for most of the presumably enlightened twentieth century, and the alienation of Dominican diaspora seeking liberty and opportunity within the contemporary United States. This paper seeks to uncover Yunior’s surfacing trauma, and explores the possibility of his bearing witness to the violence of his origins. -

Media Industry Approaches to Comic-To-Live-Action Adaptations and Race

From Serials to Blockbusters: Media Industry Approaches to Comic-to-Live-Action Adaptations and Race by Kathryn M. Frank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Lisa A. Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar © Kathryn M. Frank 2015 “I don't remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.” ― Edward W. Said, Palestine For Mom and Dad, who taught me to be my own hero ii Acknowledgements There are so many people without whom this project would never have been possible. First and foremost, my parents, Paul and MaryAnn Frank, who never blinked when I told them I wanted to move half way across the country to read comic books for a living. Their unending support has taken many forms, from late-night pep talks and airport pick-ups to rides to Comic-Con at 3 am and listening to a comics nerd blather on for hours about why Man of Steel was so terrible. I could never hope to repay the patience, love, and trust they have given me throughout the years, but hopefully fewer midnight conversations about my dissertation will be a good start. Amanda Lotz has shown unwavering interest and support for me and for my work since before we were formally advisor and advisee, and her insight, feedback, and attention to detail kept me invested in my own work, even in times when my resolve to continue writing was flagging. -

Moon-Earth-Sun: the Oldest Three-Body Problem

Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem Martin C. Gutzwiller IBM Research Center, Yorktown Heights, New York 10598 The daily motion of the Moon through the sky has many unusual features that a careful observer can discover without the help of instruments. The three different frequencies for the three degrees of freedom have been known very accurately for 3000 years, and the geometric explanation of the Greek astronomers was basically correct. Whereas Kepler’s laws are sufficient for describing the motion of the planets around the Sun, even the most obvious facts about the lunar motion cannot be understood without the gravitational attraction of both the Earth and the Sun. Newton discussed this problem at great length, and with mixed success; it was the only testing ground for his Universal Gravitation. This background for today’s many-body theory is discussed in some detail because all the guiding principles for our understanding can be traced to the earliest developments of astronomy. They are the oldest results of scientific inquiry, and they were the first ones to be confirmed by the great physicist-mathematicians of the 18th century. By a variety of methods, Laplace was able to claim complete agreement of celestial mechanics with the astronomical observations. Lagrange initiated a new trend wherein the mathematical problems of mechanics could all be solved by the same uniform process; canonical transformations eventually won the field. They were used for the first time on a large scale by Delaunay to find the ultimate solution of the lunar problem by perturbing the solution of the two-body Earth-Moon problem. -

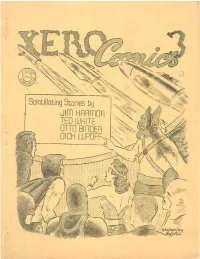

Xero Comics 3

[A/katic/Po about Wkatto L^o about ltdkomp5on,C?ou.l5on% ^okfy Madn.^5 and klollot.-........ - /dike U^eckin^z 6 ^Tion-t tke <dk<dfa............. JlaVuj M,4daVLi5 to Tke -dfec'iet o/ (2apta Ln Video ~ . U 1 _____ QilkwAMyn n 2t £L ......conducted byddit J—upo 40 Q-b iolute Keto.................. ............Vldcjdupo^ 48 Q-li: dVyL/ia Wklie.... ddkob dVtewait.... XERO continues to appall an already reeling fandom at the behest of Pat & Dick Lupoff, 21J E 7Jrd Street, New York 21, New York. Do you want to be appalled? Conies are available for contributions, trades, or letters of comment. No sales, no subs. No, Virginia, the title was not changed. mimeo by QWERTYUIOPress, as usual. A few comments about lay ^eam's article which may or lay not be helpful. I've had similar.experiences with readers joining fan clubs. Tiile at Penn State, I was president of the 3F‘Society there, founded by James F. Cooper Jr, and continued by me after he gafiated. The first meeting held each year packed them in’ the first meeting of all brought in 50 people,enough to get us our charter from the University. No subsequent meeting ever brought in more than half that, except when we held an auction. Of those people, I could count on maybe five people to show up regularly, meet ing after meeting, just to sit and talk. If we got a program together, we could double or triple that. One of the most popular was the program vzhen we invited a Naval ROTO captain to talk about atomic submarines and their place in future wars, using Frank Herbert's novel Dragon in the ~ea (or Under Pressure or 21 st Century Sub, depending upon where you read itj as a starting point. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

Roy Thomas ’ Yul e -B e -Su rprised Comics Fanzine $ No.130 January In8.95 the USA 2015 A SPECIAL HOLIDAY EDITION OF 80 PAGES STARRING CAPTAIN MARVEL with Spy Smasher, Golden Arrow, Bullet- 1 2 man, Mr. Scarlet, Commando Yank, Ibis the Invincible, Lance O’Casey, Phantom Eagle, and many others. 1 82658 27763 5 plus— Heroes TM & © DC Comics or the respective copyright holders. DAN BARRY! Vol. 3, No. 130 / January 2015 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor Paul C. Hamerlinck If you’re viewing a Digital Edition of this publication, J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) PLEASE READ THIS: Comic Crypt Editor This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our Michael T. Gilbert website or Apps. If you downloaded it from another website or torrent, go ahead and Editorial Honor Roll read it, and if you decide to keep it, DO THE RIGHT THING and buy a legal down- Jerry G. Bails (founder) load, or a printed copy. Otherwise, DELETE IT FROM YOUR DEVICE and DO NOT Ronn Foss, Biljo White SHARE IT WITH FRIENDS OR POST IT Mike Friedrich ANYWHERE. If you enjoy our publications enough to download them, please pay for Proofreaders them so we can keep producing ones like this. Our digital editions should ONLY be Rob Smentek downloaded within our Apps and at William J. Dowlding www.twomorrows.com Cover Artist C.C. Beck Contents (colorist unknown) Writer/Editorial: Keeping The “Christmas” In Christmas . 2 With Special Thanks to: The Many Facets Of Dan Barry. -

ISIS: Dark Goddess

ISIS: Dark Goddess by Thomas A. McKean – 11/30/05 http://www.thomasamckean.com (Based upon the “Secrets of Isis” series by Filmation.) Introduction Just to get the boring legal stuff out of the way, I do not own Isis or any of the characters written about in here. Having said that… What follows is a complete outline for a novel based on The Secrets of Isis Saturday morning TV series of the 1970’s, which starred Joanna Cameron (seen in the role of Isis in the picture above). Because of time limitations, I will likely not be writing the complete novel. The story ends here, with the outline. I wrote this for a few reasons. One was simply the outlining exercise. I am still learning how to outline effectively as a writer. When I wrote Soon Will Come the Light , and then later when I wrote Light on the Horizon , they were both written without an outline. Though I was fortunate to have them both published, I do feel they may have been better if I wasn’t working without a net, so to speak. Another reason is because I am a fan of the series. I felt Isis had great potential and I was sad that she never reached it. She had further potential later in the comics, but they were also cancelled before she reached it. I had always wondered about Rick and Andrea. I am sure I am not the only one who wanted to see them finally get together? Here was an opportunity. Alas, one wasted as you will see, for the story took on a mind of its own and went places I never thought it would go, and places I certainly had no intention of taking it. -

The End of the Wor(L)D As We Know It: Textuality, Agency, And

THE END OF THE WOR(L)D AS WE KNOW IT: TEXTUALITY, AGENCY, AND ENDINGS IN POSTCOLONIAL MAGICAL REALISM by Janna Mercedes Urschel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2013 © COPYRIGHT by Janna Mercedes Urschel 2013 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Janna Mercedes Urschel This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency and is ready for submission to The Graduate School. Dr. Robert Bennett Approved for the Department of English Dr. Philip Gaines Approved for The Graduate School Dr. Ronald W. Larsen iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Janna Mercedes Urschel April 2013 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the dedicated members of my thesis committee, who stuck with me through the protracted and messy process of my thought and offered sage advice and splendid encouragement: my chair, Dr. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

Roy Thomas’ Und ea d Comics Fanzine HELLZAPOPPIN’ HALLOWEEN ISSUE! $6.95 In the USA No.53 THOMAS October & GIORDANO’S 2005 DRACULA DICK BRIEFER’S FRANKENSTEIN ANDRU & & ESPOSITO’S ESPOSITO’S MISTER MYSTERY MR. MONSTER’S COMIC CRYPT AND MORE! PLUS:PLUS: [Art ©2005 Dick Giordano; Marvel Dracula TM & ©2005 Marvel Characters, Inc.] Vol. 3, No. 53 / October 2005 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout ChrisTopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. GilberT Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo WhiTe, let me show Mike Friedrich YOU more of my newspaper Production Assistant comic strip Eric Nolen-WeaThingTon samples... Cover Artist Dick Giordano Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko And Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: A-Haunting We Will Go! . 2 ChrisTian VolTar JosTein Hansen Alcala & Family Jack C. Harris Heidi Amash Daniel Herman Three Decades Of Dracula —And Coun ting . 3 Tom Andrae Carmine InfanTino Giordano, Thomas, & Beazley on The 30-year voyage of Stoker’s Dracula . David ArmsTrong Rob Jones Ger Apeldoorn Michael W. KaluTa Happy Halloween! . 15 Joan AppleTon Richard Kyle HaunTed arT by WrighTson, Brunner, HeaTh, KaluTa, Alcala, DiTko, BisseTTe, EvereTT, eT al. Rodrigo Baeza Phil LaTTer PaT BasTienne Mark Luebker Michael BauldersTone Mike Mignola Frankenstein In The Funny Pages? – Part II . 26 AlberTo BecaTTini Mike Mikulolvsky Dick Briefer and his MonsTer-ous newspaper sTrip—a special A/E comics secTion. Richard Beaizley Fred Mommsen Mark Beazley MaTT Moring Allen Bellman Brian K. Morris “Ross Andru And I Had A Handshake Partnership John Benson Frank MoTler Daniel BesT Will Murray That Lasted Until The Day He Died” . -

Ancient Thunder Study Guide 2021 1

BTE • Ancient Thunder Study Guide 2021 1 Ancient Thunder Study Guide In this study guide you will find all kinds of information to help you learn more about the myths that inspired BTE's original play Ancient Thunder, and about Ancient Greece and its infleunce on culture down to the present time. What is Mythology? ...................................................2 The stories the actors tell in Ancient Thunder are called myths. Learn what myths are and how they are associated with world cultures. When and where was Ancient Greece? ..................... 10 The myths in Ancient Thunder were created thousands of years ago by people who spoke Greek. Learn about where and when Ancient Greece was. What was Greek Art like? ..........................................12 Learn about what Greek art looked like and how it inspired artists who came after them. How did the Greeks make Theatre? .......................... 16 The ancient Greeks invented a form of theatre that has influenced storytelling for over two thousand years. Learn about what Greek theatre was like. What was Greek Music like? ..................................... 18 Music, chant, and song were important to Greek theatre and culture. Learn about how the Greeks made music. What are the Myths in Ancient Thunder? ................. 20 Learn more about the Greek stories that are told in Ancient Thunder. Actvities ........................................................................................................... 22 Sources ..............................................................................................................24 Meet the Cast .................................................................................................... 25 2 BTE • Ancient Thunder Study Guide 2021 What is Mythology? Myths are stories that people tell to explain and understand how things came to be and how the world works. The word myth comes from a Greek word that means story. Mythology is the study of myths. -

The Magic Flute

The Magic Flute Opera Box Table of Contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .9 Reference/Tracking Guide . .10 Lesson Plans . .13 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – a biography ......................49 Catalogue of Mozart’s Operas . .51 Background Notes . .53 Emanuel Schikaneder, Mozart and the Masons . .57 World Events in 1791 ....................................63 History of Opera ........................................66 2003 – 2004 SEASON History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .77 The Standard Repertory ...................................81 Elements of Opera .......................................82 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................86 GIUSEPPE VERDI NOVEMBER 15 – 23, 2003 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................92 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .95 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .98 GAETANO DONIZETTI JANUARY 24 – FEBRUARY 1, 2004 Evaluation . .101 Acknowledgements . .102 STEPHEN SONDHEIM FEBRUARY 28 – MARCH 6, 2004 mnopera.org WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART MAY 15 – 23, 2004 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. -

Shazam! : the Golden Age of the Worlds Mightiest Mortal Kindle

SHAZAM! : THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE WORLDS MIGHTIEST MORTAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chip Kidd | 246 pages | 05 Mar 2019 | Abrams | 9781419737473 | English | New York, United States Shazam! : The Golden Age of the Worlds Mightiest Mortal PDF Book Learn more. This is a beautiful book showcasing a visual history with text of one of the Golden Age's most celebrated heroes, Captain Marvel. Start your review of Shazam! You can renew your subscription or continue to use the site without a subscription. Verified purchase: Yes Condition: New. Geoff Johns Hardcover Books. In , the film Shazam! Handling time. Chip Kidd. Abrams , pp. The 8 year-old sent the writer a letter asking for an interview, telling him, "I'm 13, but I'm a professional writer for a fanzine. First Edition. Skip to main content. A must for Shazam fans! Cyberpunk Volume 1: Trauma Team. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. Buy It Now. Detective Comics comes a Chip Kidd is a noted graphic designer and comic enthusiast! In the Johns story, he added a clause that Shazam needed to say his name with meaning to transform, but in the movie any attempt made by Shazam to say his own name will result in him transforming back into Billy Batson. Prometheus: Fire and Stone. No advertising. There are 1 items available. It was also fascinating to read how much the war effort reached out to the young readers of comics, boys and girls. Joe Gill and Steve Ditko. Sign in. Kidd recounts the battle that Captain Marvel lost — the one in the courtroom.