Reflections on the Creative and Technological Development of the Audiovisual Duo—The Rebel Scum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

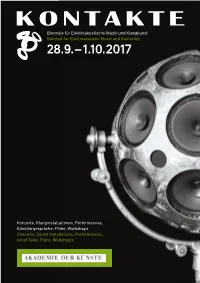

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

French Underground Raves of the Nineties. Aesthetic Politics of Affect and Autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin

French underground raves of the nineties. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin To cite this version: Jean-Christophe Sevin. French underground raves of the nineties. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy. Political Aesthetics: Culture, Critique and the Everyday, Arundhati Virmani, pp.71-86, 2016, 978-0-415-72884-3. halshs-01954321 HAL Id: halshs-01954321 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01954321 Submitted on 13 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. French underground raves of the 1990s. Aesthetic politics of affect and autonomy Jean-Christophe Sevin FRENCH UNDERGROUND RAVES OF THE 1990S. AESTHETIC POLITICS OF AFFECT AND AUTONOMY In Arundhati Virmani (ed.), Political Aesthetics: Culture, Critique and the Everyday, London, Routledge, 2016, p.71-86. The emergence of techno music – commonly used in France as electronic dance music – in the early 1990s is inseparable from rave parties as a form of spatiotemporal deployment. It signifies that the live diffusion via a sound system powerful enough to diffuse not only its volume but also its sound frequencies spectrum, including infrabass, is an integral part of the techno experience. In other words listening on domestic equipment is not a sufficient condition to experience this music. -

An AI Collaborator for Gamified Live Coding Music Performances

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Falmouth University Research Repository (FURR) Autopia: An AI Collaborator for Gamified Live Coding Music Performances Norah Lorway,1 Matthew Jarvis,1 Arthur Wilson,1 Edward J. Powley,2 and John Speakman2 Abstract. Live coding is \the activity of writing (parts of) regards to this dynamic between the performer and audience, a program while it runs" [20]. One significant application of where the level of risk involved in the performance is made ex- live coding is in algorithmic music, where the performer mod- plicit. However, in the context of the system proposed in this ifies the code generating the music in a live context. Utopia3 paper, we are more concerned with the effect that this has on is a software tool for collaborative live coding performances, the performer themselves. Any performer at an algorave must allowing several performers (each with their own laptop pro- be prepared to share their code publicly, which inherently en- ducing its own sound) to communicate and share code during courages a mindset of collaboration and communal learning a performance. We propose an AI bot, Autopia, which can with live coders. participate in such performances, communicating with human performers through Utopia. This form of human-AI collabo- 1.2 Collaborative live coding ration allows us to explore the implications of computational creativity from the perspective of live coding. Collaborative live coding takes its roots from laptop or- chestra/ensemble such as the Princeton Laptop Orchestra (PLOrk), an ensemble of computer based instruments formed 1 Background at Princeton University [19]. -

Phylogenetic Reconstruction of the Cultural Evolution of Electronic Music Via Dynamic Community Detection (1975–1999)

Phylogenetic reconstruction of the cultural evolution of electronic music via dynamic community detection (1975{1999) Mason Youngblooda,b,1, Karim Baraghithc, and Patrick E. Savaged a Department of Psychology, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA bDepartment of Biology, Queens College, City University of New York, Flushing, NY, USA cDepartment of Philosophy, DCLPS, Heinrich-Heine University, D¨usseldorf,NRW, Germany dFaculty of Environment and Information Studies, Keio University SFC, Fujisawa, Japan [email protected] Abstract Cultural phylogenies, or \trees" of culture, are typically built using methods from biology that use similarities and differences in artifacts to infer the historical relationships between the populations that produced them. While these methods have yielded important insights, particularly in linguistics, researchers continue to debate the extent to which cultural phylogenies are tree-like or reticulated due to high levels of horizontal transmission. In this study, we propose a novel method for phylogenetic reconstruction using dynamic community detection that explicitly accounts for transmission between lineages. We used data from 1,498,483 collaborative relationships between electronic music artists to construct a cultural phylogeny based on observed population structure. The results suggest that, although the phylogeny is fun- damentally tree-like, horizontal transmission is common and populations never become fully isolated from one another. In addition, we found evidence that electronic music diversity has increased between 1975 and 1999. The method used in this study is available as a new R package called DynCommPhylo. Future studies should apply this method to other cultural systems such as academic publishing and film, as well as biological systems where high resolution reproductive data is available, to assess how levels of reticulation in evolution vary across domains. -

Spaces to Fail In: Negotiating Gender, Community and Technology in Algorave

Spaces to Fail in: Negotiating Gender, Community and Technology in Algorave Feature Article Joanne Armitage University of Leeds (UK) Abstract Algorave presents itself as a community that is open and accessible to all, yet historically, there has been a lack of diversity on both the stage and dance floor. Through women- only workshops, mentoring and other efforts at widening participation, the number of women performing at algorave events has increased. Grounded in existing research in feminist technology studies, computing education and gender and electronic music, this article unpacks how techno, social and cultural structures have gendered algorave. These ideas will be elucidated through a series of interviews with women participating in the algorave community, to centrally argue that gender significantly impacts an individual’s ability to engage and interact within the algorave community. I will also consider how live coding, as an embodied techno-social form, is represented at events and hypothesise as to how it could grow further as an inclusive and feminist practice. Keywords: gender; algorave; embodiment; performance; electronic music Joanne Armitage lectures in Digital Media at the School of Media and Communication, University of Leeds. Her work covers areas such as physical computing, digital methods and critical computing. Currently, her research focuses on coding practices, gender and embodiment. In 2017 she was awarded the British Science Association’s Daphne Oram award for digital innovation. She is a current recipient of Sound and Music’s Composer-Curator fund. Outside of academia she regularly leads community workshops in physical computing, live coding and experimental music making. Joanne is an internationally recognised live coder and contributes to projects including laptop ensemble, OFFAL and algo-pop duo ALGOBABEZ. -

Download the Conference Abstracts Here

THURSDAY 8 SEPTEMBER 2016: SESSIONS 1‐4 Maciej Fortuna and Krzysztof Dys (Academy of Music, Poznán) BIOGRAPHIES Maciej Fortuna is a Polish trumpeter, composer and music producer. He has a PhD degree in Musical Arts and an MA degree in Law and actively pursues his artistic career. In his work, he strives to create his own language of musical expression and expand the sound palette of his instrument. He enjoys experimenting with combining different art forms. An important element of his creative work consists in the use of live electronics. He creates and directs multimedia concerts and video productions. Krzysztof Dys is a Polish jazz pianist. He has a PhD degree in Musical Arts. So far he has collaborated with the great Polish vibrafonist Jerzy Milian, with famous saxophonist Mikoaj Trzaska, and as well with clarinettist Wacaw Zimpel. Dys has worked on a regular basis with young, Poznań‐based trumpeter, Maciej Fortuna. Their album Tropy has been well‐received by the audience and critics as well. Dys also plays in Maciej Fortuna Quartet, with Jakub Mielcarek, double bass, and Przemysaw Jarosz, drums. In 2013 the group toured outside Poland with a project ‘Jazz from Poland’, with a goal to present the work of unappreciated or forgotten or Polish jazz composers. The main inspiration for Krzysztof Dys is the work of Russian composers Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev, American artists like Bill Evans and Miles Davis, and last but not least, a great Polish composer, Grayna Bacewicz. TITLE Classical Inspirations in Jazz Compositions Based on Selected Works by Roman Maciejewski ABSTRACT A few years prior to commencing a PhD programme, I started my own research on the possibilities of implementing electronic sound modifiers into my jazz repertoire. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

Politizace Ceske Freetekno Subkultury

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ Katedra sociologie POLITIZACE ČESKÉ FREETEKNO SUBKULTURY Diplomová práce Jan Segeš Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Csaba Szaló, Ph.D. UČO: 137526 Obor: Sociologie Imatrikulační ročník: 2009 Brno, 2011 Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji, ţe jsem diplomovou práci „Politizace české freetekno subkultury“ vypracoval samostatně a pouze s pouţitím pramenů uvedených v seznamu literatury. ................................... V Brně dne 15. května 2011 Jan Segeš Poděkování Děkuji doc. PhDr. Csabovi Szaló, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce a za podnětné připomínky, které mi poskytl. Dále děkuji RaveBoyovi za ochotu odpovídat na mé otázky a přístup k archivu dokumentů. V neposlední řadě děkuji svým rodičům a prarodičům za jejich podporu v průběhu celého mého studia. ANOTACE Práce se zabývá politizací freetekno subkultury v České Republice. Politizace je v nahlíţena ve dvou dimenzích. První dimenzí je explicitní politizace, kterou můţeme vnímat jako aktivní politickou participaci. Druhou dimenzí je politizace na úrovni kaţdodenního ţivota. Ta je odkrývána díky re-definici subkultury pomocí post- subkulturních teorií, zejména pak Maffesoliho konceptem neotribalismu a teorie dočasné autonomní zóny Hakima Beye. Práce se snaţí odkrýt obě úrovně politizace freetekno subkultury v českém prostředí pomocí analýzy dostupných dokumentů týkajících se teknivalů CzechTek, CzaroTek a pouličního festivalu DIY Karneval. Rozsah práce: základní text + poznámky pod čarou, titulní list, obsah, rejstřík, anotace a seznam literatury je 138 866 znaků. Klíčová slova: freetekno, politizace, dočasná autonomní zóna, DAZ, neo-kmen, neotribalismus, CzechTek, subkultura, post-subkultury ANNOTATION The presented work focuses on the politicization of the freetekno subculture in the Czech Republic. The politicization is perceived in two dimensions. The first dimension is the explicit politicization, which could be represented as the active political participation. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 60Th Annual Meeting, 2015 Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 60th Annual Meeting, 2015 Abstracts Walking, Parading, and Footworking Through the City: Urban collectively entrained and individually varied. Understanding their footwork Processional Music Practices and Embodied Histories as both an enactment of sedimented histories and a creative process of Marié Abe, Boston University, Chair, – Panel Abstract reconfiguring the spatial dynamics of urban streets, I suggest that a sense of enticement emerges from the oscillation between these different temporalities, In Michel de Certeau’s now-famous essay, “Walking the City,” he celebrates particularly within the entanglement of western imperialism and the bodily knowing of the urban environment as a resistant practice: a relational, development of Japanese capitalist modernity that informed the formation of kinesthetic, and ephemeral “anti-museum.” And yet, the potential for one’s chindon-ya. walking to disrupt the social order depends on the walker’s racial, ethnic, gendered, national and/or classed subjectivities. Following de Certeau’s In a State of Belief: Postsecular Modernity and Korean Church provocations, this panel investigates three distinct urban, processional music Performance in Kazakhstan traditions in which walking shapes participants’ relationships to the past, the Margarethe Adams, Stony Brook University city, and/or to each other. For chindon-ya troupes in Osaka - who perform a kind of musical advertisement - discordant walking holds a key to their "The postsecular may be less a new phase of cultural development than it is a performance of enticement, as an intersection of their vested interests in working through of the problems and contradictions in the secularization producing distinct sociality, aesthetics, and history. For the Shanghai process itself" (Dunn 2010:92). -

Dancecult Bibliography: Books, Articles, Theses, Lectures, and Films About Electronic Dance Music Cultures

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2010 Dancecult Bibliography: Books, Articles, Theses, Lectures, and Films About Electronic Dance Music Cultures Eliot Bates CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/408 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] archive.today Saved from http://www.dancecult.net/bibliography.php search 3 Sep 2013 05:47:40 UTC webpage capture history All snapshots from host www.dancecult.net Linked from en.wikipedia.org » Talk:Trance (music genre)/Archive 1 Webpage Screenshot share download .zip report error or abuse Electronic dance music cultures bibliography Help expand this bibliography by submitting new references to dancecult! Complete list [sort by document type] [printable] [new entries] Abreu, Carolina. 2005. Raves: encontros e disputas. M.A. Thesis (Anthropology), University of São Paulo. [view online] Albiez, Sean and Pattie, David (eds.). 2010. Kraftwerk: Music Non Stop. New York / London: Continuum. [view online] Albiez, Sean. 2003. "'Strands of the Future: France and the birth of electronica'." Volume! 2003(2), 99-114. Albiez, Sean. 2003. "Sounds of Future Past: from Neu! to Numan." In Pop Sounds: Klangtexturen in der Pop- und Rockmusik, edited by Phleps, Thomas & von Appen, Ralf. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 129-152. Albiez, Sean. 2005. "Post Soul Futurama: African American cultural politics and early Detroit Techno." European Journal of American Culture 24(2), 131-152. -

Digital Music Distribution

#149 Feb/Mar 08 www.mushroom-online.com Digital Music Distribution Skazi • Space Buddha • SCM • Materia • Doof psychedelic trance guide Universo Paralello • World Psychedelic Forum mushroom2008-02.indd 1 01.02.2008 15:13:33 Uhr mushroom2008-02.indd 2 01.02.2008 15:13:36 Uhr WELCOME 3 Impressum New Model Army to the Galaxy ... Verlagsanschrift / Address Willkommen im neuen Jahr zu unse- Welcome to the new year, and our Feb- FORMAT Promotion GmbH rer Februar/März-Doppelausgabe und ruary/March double issue. First off a big Arnoldstraße 47 ein ganz großes SORRY, dass wir die- apology for the magazine appearing so 22763 Hamburg sen Monat erst so spät erschienen sind. late this month. The reason for this was Germany Grund dafür war der Trancers Guide To that due to a few delays the Trancers HRB 98417 Hamburg The Galaxy 2008, der aufgrund einiger Guide To The Galaxy 2008 had to be pro- fon: +49 40 398417-0 Verspätungen letztendlich gleichzeitig duced at the same time as mushroom fax: +49 40 398417-50 mit dem mushroom produziert werden magazine. An interesting fact: the TTG [email protected] musste. Der wird übrigens im Laufe des will be translated into Portuguese in www.mushroom-media.com Monats ins Portugiesische übersetzt und the coming month, and 20.000 of it will Herausgeber / Publisher im Frühjahr in einer Zusatzauflage von be distributed n spring in Brazil as an Matthias van den Nieuwendijk (V.i.S.d.P.) 20.000 Heften in Brasilien verteilt. extra edition. Redaktionsleitung / Chief Editor Liese Neue Projekte schießen sowieso wie Lately new projects have been popping Redaktion / Editorial Team Pilze aus dem Boden. -

Networks of Liveness in Singer-Songwriting

Networks of Liveness in Singer-Songwriting: A practice-based enquiry into developing audio-visual interactive systems and creative strategies for composition and performance. Figure 1: Performance of Church Belles at Leeds International Festival of Artistic Innovation, 2016. Photo by George Yonge. Used with permission. Simon Waite P11037253 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2018 Abstract This enquiry explores the creation and use of computer-based, real-time interactive audio- visual systems for the composition and performance of popular music by solo artists. Using a practice-based methodology, research questions are identified that relate to the impact of incorporating interactive systems into the songwriting process and the liveness of the performances with them. Four approaches to the creation of interactive systems are identified: creating explorative-generative tools, multiple tools for guitar/vocal pieces, typing systems and audio-visual metaphors. A portfolio of ten pieces that use these approaches was developed for live performance. A model of the songwriting process is presented that incorporates system-building and strategies are identified for reconciling the indeterminate, electronic audio output of the system with composed popular music features and instrumental/vocal output. The four system approaches and ten pieces are compared in terms of four aspects of liveness, derived from current theories. It was found that, in terms of overall liveness, a unity to system design facilitated both technological and aesthetic connections between the composition, the system processes and the audio and visual outputs. However, there was considerable variation between the four system approaches in terms of the different aspects of liveness.