Kieran Craig Cody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater

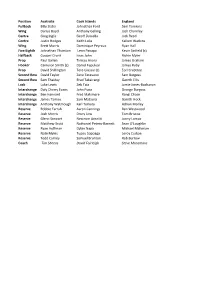

Position Australia Cook Islands England Fullback Billy Slater Johnathan Ford Sam Tomkins Wing Darius Boyd Anthony Gelling Josh Charnley Centre Greg Inglis Geoff Daniella Jack Reed Centre Justin Hodges Keith Lulia Kallum Watkins Wing Brett Morris Dominique Peyroux Ryan Hall Five Eighth Johnathan Thurston Leon Panapa Kevin Sinfield (c) Halfback Cooper Cronk Issac John Richie Myler Prop Paul Gallen Tinirau Arona James Graham Hooker Cameron Smith (c) Daniel Fepuleai James Roby Prop David Shillington Tere Glassie (c) Eorl Crabtree Second Row David Taylor Zane Tetevano Sam Burgess Second Row Sam Thaiday Brad Takairangi Gareth Ellis Lock Luke Lewis Zeb Taia Jamie Jones-Buchanan Interchange Daly Cherry Evans John Puna George Burgess Interchange Ben Hannant Fred Makimare Rangi Chase Interchange James Tamou Sam Mataora Gareth Hock Interchange Anthony Watmough Karl Temata Adrian Morley Reserve Robbie Farrah Aaron Cannings Ben Westwood Reserve Josh Morris Drury Low Tom Briscoe Reserve Glenn Stewart Neccrom Areaiiti Jonny Lomax Reserve Matthew Scott Nathaniel Peteru-Barnett Sean O'Loughlin Reserve Ryan Hoffman Dylan Napa Michael Mcllorum Reserve Nate Myles Tupou Sopoaga Leroy Cudjoe Reserve Todd Carney Samuel Brunton Rob Burrow Coach Tim Sheens David Fairleigh Steve Mcnamara Fiji France Ireland Italy Jarryd Hayne Tony Gigot Greg McNally James Tedesco Lote Tuqiri Cyril Stacul John O’Donnell Anthony Minichello (c) Daryl Millard Clement Soubeyras Stuart Littler Dom Brunetta Wes Naiqama (c) Mathias Pala Joshua Toole Christophe Calegari Sisa Waqa Vincent -

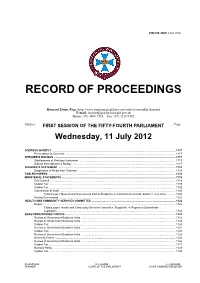

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-assembly/hansard E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-FOURTH PARLIAMENT Page Wednesday, 11 July 2012 ADDRESS-IN-REPLY ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1117 Presentation to Governor ................................................................................................................................................... 1117 SPEAKER’S RULINGS .................................................................................................................................................................. 1117 Disallowance of Statutory Instrument ................................................................................................................................. 1117 Dissent from Speaker’s Ruling ........................................................................................................................................... 1117 SPEAKER’S STATEMENT ............................................................................................................................................................ 1118 Suspension of Media from Chamber .................................................................................................................................. 1118 TABLED PAPERS ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

2010 Annual Report & Statement of Accounts

2010 AnnuAl RepoRt & Statement of Accounts Wellington Rugby Football union (Incorporated) Annual Report 2010 Contents list of officers ................................................................................................................... 2 Honours and Awards ........................................................................................................ 3 Balanced Scoreboard ........................................................................................................ 4 Chairman’s Report ............................................................................................................ 5 Rugby Board Report .......................................................................................................... 7 team Reports ...................................................................................................................... Hurricanes ................................................................................................................ 8 Vodafone Wellington lions ..................................................................................... 11 Wellington pride ..................................................................................................... 15 Wellington Development ........................................................................................ 16 Wellington u20 ...................................................................................................... 17 Wellington u20 Development ................................................................................ -

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson

TO: NZRL Staff, Districts and Affiliates and Board FROM: Cushla Dawson DATE: 28 October 2008 RE: Media Summary Wednesday 29 October to Monday 03 November 2008 Slater takes place among the greats: AUSTRALIA 52 ENGLAND 4. Billy Slater last night elevated himself into the pantheon of great Australian fullbacks with a blistering attacking performance that left his coach and Kangaroos legend Ricky Stuart grasping for adjectives. Along with Storm teammate and fellow three-try hero Greg Inglis, Slater turned on a once-in-a-season performance to shred England to pieces and leave any challenge to Australia's superiority in tatters. It also came just six days after the birth of his first child, a baby girl named Tyla Rose. Kiwis angry at grapple tackle: The Kiwis are fuming a dangerous grapple tackle on wing Sam Perrett went unpunished in last night's World Cup rugby league match but say they won't take the issue further. Wing Sam Perrett was left lying motionless after the second tackle of the match at Skilled Park, thanks to giant Papua New Guinea prop Makali Aizue. Replays clearly showed Aizue, the Kumuls' cult hero who plays for English club Hull KR, wrapping his arm around Perrett's neck and twisting it. Kiwis flog Kumuls: New Zealand 48 Papua New Guinea NG 6. A possible hamstring injury to Kiwis dynamo Benji Marshall threatened to overshadow his side's big win over Papua New Guinea at Skilled Park last night. Arguably the last superstar left in Stephen Kearney's squad, in the absence of show-stoppers like Roy Asotasi, Frank Pritchard and Sonny Bill Williams, Marshall is widely considered the Kiwis' great white hope. -

Your FREE Magazine from Your Local NHS We Meet... Kevin Sinfield Volunteering Opportunities Care for Dementia Competitions and Quizzes Plus

EngageIssue One: October 2014 Your FREE magazine from your local NHS We meet... Kevin Sinfield Volunteering opportunities Care for dementia Competitions and quizzes Plus... lots more! Start as we mean to go on? Well here we are breaking new ground as we launch our first ever community Contents magazine, we hope you 03 Get involved with 10 Making Leeds share this with friends your local NHS child friendly across the city. To help us There’s lots of ways you can Find out more about the Breeze ‘try’ to ‘tackle’ our first game help your local NHS so that programme and a new app we can develop the best tackling the perils of sexting nerves (ok no more rugby possible services metaphors!) we interviewed 11 Cinnamon doesn’t 04 Volunteering makes a quite make the grade Kevin Sinfield, captain of difference at Hollybush Find out why we have done Leeds Rhinos Rugby League 05 Breaking new ground a cinnamon review! club. He tells us about how in patient involvement 12 Spotlight on… Armley he prepares for a game, A first for the CCG… There’s more to Armley than what got him playing in find out why you might think the first place and why he 06 Kevin Sinfield interview 13 News in brief We met up with ‘Sinny’ and Catch up on the latest local never lets asthma get in the talked about rugby, asthma updates you might have missed way of being a world beater. and life as a captain 14 Competition and quizzes So what else have we got in 08 A day in the life of… Win a signed Leeds Rhinos shirt Want to know what life is like 15 Gardening guru our first edition… some great as a pharmacist in the medicines Our resident gardening expert optimisation team gardening tips, a review of takes a break from the outdoors an app protecting children 09 Caring for someone to bring you some top tips with dementia from the perils of sexting 16 Sports round up Barbara tells us more about and a special mention to Local football club celebrates her experience as one of the a special birthday local football club Wortley city’s 70,000 unpaid carers FC for reaching their 40th anniversary. -

2017 Season Review

2017 Season Review Paul Hampton For the first time in Castleford’s 91 year history as a senior club they finished at the top of the table. After the regular season of 23 games the twelve team league split into the Super 8s at the top, with the bottom four joining with the Championship top four in the Qualifiers to determine promotion and relegation. Castleford finished the regular season at the top, ten points clear and maintained the lead to the end of the season. They were so far in front that the shield was awarded to them after only three games of the seven game series as they could not be caught. Final Table 2017 P W D L FOR AGST DIFF PTS Castleford Tigers 30 25 0 5 965 536 429 50 Leeds Rhinos 30 20 0 10 749 623 126 40 Hull FC 30 17 1 12 714 655 59 35 St Helens 30 16 1 13 663 518 145 33 Wakefield Trinity 30 16 0 14 745 648 97 32 Wigan Warriors 30 14 3 13 691 668 23 31 Salford Red Devils 30 14 0 16 680 728 -48 28 Huddersfield Giants 30 11 3 16 663 680 -17 25 The record breaking season was one of many achievements – • Luke Gale voted Man of Steel and RL Writers Association Player of the Year. He also won the League Express magazine Albert Goldthorpe Medal as Player of the Season for the third consecutive time. • Daryl Powell voted Coach of The Year • Castleford Tigers voted Club of The Year • Luke Gale topped the goal scoring list with 145 and was top points scorer in the league with 355 • Greg Eden was top try scorer in the League with 41 in all competitions • The club won the league by a record Super League margin of 10 points and equalled the highest points of 50. -

Critic-2020-1-Pdf.Pdf

1 1 2 2 3 3 4 HEADQUARTERS OTAGO HARBOUR GOLF 10% student discount. HAIRDRESSING CHALLENGE CENTRE CITY & GEORGE STREET 2-for-1 water hire (paddle boards, single and tandem kayaks). Hire one and get CAPERS CAFE Cut & blow-wave + treatment + Wella take another free for a friend with your home product for $100. 2-for-1 gourmet pancakes. Onecard. 9am Monday – 3pm Friday. Monday to Friday only. Subject to availability/weather. T&C’s SHOSHA apply. CORNERSTONE INK 10% student discount. TATTOO STUDIO Phone SURGEONS 10% discount off any tattoo, not in LUMINO THE 50% off all phone, tablet, laptop, computer conjunction with other special. & console repairs (labour only) or 25% off DENTISTS non-branded cases & accessories. $69 new patient exam (and more...). IRESURRECT subway $20 discount on any repair. UBS ON CAMPUS Buy any six-inch meal-deal and upgrade 10% discount off full-priced items. to a foot-long meal-deal for free. NANDO’S Free regular PERi-PERi Chips (or normal) TM AUTOMOTIVE ZAIBATSU HAIR ART with any main meal purchase. $52 warrant of fitness. Half head foil, cut and style treatment for $139. STIRLING SPORTS GELATO JUNKIE LA PORCHETTA 10% student discount on any full-price items. Receive $1 off double scoop ice cream with Onecard. 10% discount off all food and drinks. ONLY UR’S BEAUTY sal’s pizza EPICDOG PARLOUR One large cheese and one large Free fries with any dog over $10 with Brow and Brazilian Maintenance for $39. pepperoni for $40. Wed 26 Feb only. onecard. CHECK OUT MORE DISCOUNTS AT r1.co.nz/onecard 4 5 CRITIC MERCH NOW AVAILABLE ONLINE criticstore.com 5 6 recently, I’ve noticed the quality of Apology sandwich making in Dunedin has slipped to an incredibly inadequate standard. -

The International World of Sport and the Liability for Off-Field Indiscretions

Bond Law Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 3 2011 The nI ternational World of Sport and the Liability for Off-Field Indiscretions Chris Davies Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.bond.edu.au/blr This Article is brought to you by the Faculty of Law at ePublications@bond. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bond Law Review by an authorized administrator of ePublications@bond. For more information, please contact Bond University's Repository Coordinator. The nI ternational World of Sport and the Liability for Off-Field Indiscretions Abstract The recent terminations of the contracts of NRL player, Joel Monaghan and the AFL’s Brendan Fevola, for off-field indiscretions, has highlighted the significance of the bringing the game into disrepute clauses contained in standard player contracts. Tiger Woods’ extra-marital affairs received extensive world wide media attention, and the outcome of this negative coverage was the loss of millions of dollars in sponsorship deals. This indicates that such contracts can be terminated on the basis that a sportsperson’s behaviour was having a negative impact on the sponsor’s image. It is for the same reason that sponsors have put pressure on the governing bodies of team sports to take appropriate action for off-field indiscretions. The Court of Arbitration in D’Arcy v Australian Olympic Committee, has also held that a competitor’s behaviour in an incident where criminal charges were laid, may, in itself be sufficient to bring a sport, or themselves, into disrepute, regardless of whether the competitor is later found guilty or innocent. -

MEDIA GUIDE Cariparma Test Match 2009 FEDERAZIONE ITALIANA RUGBY

NUOVA ZELANDA MILANO SUDAFRICA UDINE SAMOA ASCOLI 8 - 28 novembre 2009 Indice Il saluto del Presidente . 2 La Federazione Italiana Rugby . 3 Calendario Cariparma Test Match 2009 . 4 Calendario Nazionale “A” . 5 Gli arbitri dei Cariparma Test Match . 6 I test-match dell’Italia nel 2008/2009 . 8 La Nazionale Italiana . 14 Gli avversari dei Cariparma Test Match 2009 . 16 Nuova Zelanda . 16 Sudafrica . 17 Samoa . 18 Lo staff azzurro . 19 Gli Azzurri . 30 Lo staff della Nazionale “A” . 48 La Nazionale “A” . 49 Statistiche . 58 Programma stampa . 64 Numeri utili . 68 Il saluto del Presidente La Nazionale ritorna in campo. Dopo l’impegnativo tour estivo , vissuto nell’emisfero australe , gli azzurri di Nick Mallett si pre - sentano al via di una nuova stagione che inizia con il tradiziona - le trittico autunnale rappresentato dai test match Cariparma. Una serie di importanti ed attesi confronti che si esauriscono, in rapida successione, in quindici giorni . L’Italia riprende il cammino da dove, praticamente, l’aveva interrotto. I primi avversari del quindici azzurro, infatti, sono i mitici e leggendari All Blacks, affrontati a fine giugno a Christchurch, che modellano una squadra da sogno. E la sfida, con un antagonista di assoluto richiamo e di simile lignaggio, si disputa nel catino di San Siro che, nell’occasione come nelle più importanti competizioni calcisti - che, fa registrare il tutto esaurito. Dal tempio milanese la Nazionale, sette giorni più tardi, si trasferisce a Udine per soste - nere un esame di elevata insidia e di grande fascino. In Friuli, infatti, gli azzurri affron - tano nientemeno che i campioni del mondo del Sudafrica. -

The House of Oojah Audiobooks New Zealand Kiwi Audio CD Mp3

The House of Oojah AudioBooks New Zealand Kiwi Audio CD mp3 - www.Audio-Books.co.nz Murder hearing told of Mob texts . Murder hearing told of Mob texts The Tuesday, 19 August MURDER ACCUSED: Quentin Duff, accused of murdering his partner, during depositions hearing at Porirua District Court. Dog, can you come to the pad? My Mrs is dead. Duff, a patched Mongrel Mob member, is accused of beating his partner of eight years, Bronwyn Aroha Whakaneke, 33, with a metal scaffolding pipe before dumping her outside a bus at the mob headquarters in Waitangirua. The text message, allegedly sent by murder accused Quentin Duff to a Mongrel Mob associate soon after Duff's partner's death, was among several revealed in Porirua District Court yesterday. Duff, who has yet to enter a plea, appeared expressionless in court yesterday for a depositions hearing. Her naked and battered body was found on January 8. Phone records in court revealed that before police were called, Duff text-messaged a Mongrel Mob associate: . It will determine if he will face trial... Duff later text-messaged the same associate from the police station: Dog, I'm examining at a lot of jail now. dog, can you come to the pad? My Mrs is dead. Tell me you didn't bro. The associate replied: I want to believe you didn't do it. Duff replied: I'm in a lot of sh. Getting no response he added: Come on, bark back. at the moment.. Another text from Duff to the associate said: Dog, I'm sorry I just f. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 1st August 2018 Newsletter #228 We May Not Have Won But It Was Fantastic Meeting All The Fans! What the hell was that? By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan ELL THAT was disappointing. This time last year we were deader than a dead thing, WSomeone forgot to tell the Titans they were canon-fodder for anyone. easy-beats. No one gave us a snowball’s chance in hell of being For the first 40 minutes they looked average, as in anything different this year – pretty much everyone fairness did we, a pretty good Shaun Johnson try tipping us for the wooden-spoon, yet here we are, apart. still eighth even after the disappointment in Queens- land. For the next 40 minutes they looked like world-beat- ers, and it was us who looked like, well, the Titans. But the Titans are a side we really should have had the depth, skill and courage to beat. We were without Tohu Harris, Adam Blair and Issac Luke, and boy did we miss them. If we lose to the Dragons this week, which most would certainly tip us to do, we will be in a tighter Simon Mannering had to wear the No 13 jersey and spot than we deserve. did not have his happiest day. Those who love knocking our boys will be all over On the other hand I was delighted to see Leivaha radio doing what they always do, shouting chokers Pulu back after way too long out. -

Kader Der All Blacks Fã¼r Iveco Series Geschrieben Von King Carlos - 02.06.2009 12:52 ______

Kader der All Blacks für Iveco series Geschrieben von king carlos - 02.06.2009 12:52 _____________________________________ Blues John Afoa – Auckland Jerome Kaino - Auckland Keven Mealamu - Auckland Josevata Rokocoko - Auckland Isaia Toeava - Auckland Ali Williams - Auckland Tony Woodcock - North Harbour Rudi Wulf - North Harbour Hurricanes Cory Jane – Wellington Ma’a Nonu - Wellington Piri Weepu - Wellington Conrad Smith - Wellington Neemia Tialata - Wellington Andrew Hore – Taranaki Chiefs Stephen Donald – Waikato Richard Kahui – Waikato Liam Messam - Waikato Mils Muliaina - Waikato Brendon Leonard - Waikato Tanerau Latimer * - Bay of Plenty Crusaders Wyatt Crockett * - Canterbury Kieran Read - Canterbury Isaac Ross * - Canterbury Brad Thorn - Canterbury Highlanders Adam Thomson - Otago Jimmy Cowan – Southland Hintermannschaft: Mils Muliaina (C), Cory Jane, Joe Rokocoko, Rudi Wulf, Richard Kahui, Conrad Smith, Isaia Toeava, Ma'a Nonu, Stephen Donald, Piri Weepu, Jimmy Cowan, Brendon Leonard. Stürmer: Jerome Kaino, Tanerau Latimer, Adam Thomson, Liam Messam, Kieran Read, Brad Thorn, Ali Williams, Isaac Ross, John Afoa, Neemia Tialata, Tony Woodcock, Wyatt Crockett, Andrew Hore, Keven Mealamu. *Erste Berufung **Verletzte: Richie McCaw, Anthony Boric, Scott Waldrom, Sitiveni Sivivatu, Andy Ellis, Corey Flynn, Daniel Carter...Rodney So'oialo ist nicht verletzt, darf aber pausieren Junior All Blacks: Ryan Crotty, Canterbury, Israel Dagg, Hawke’s Bay Aled de Malmanche, Waikato Tom Donnelly, Otago Jason Eaton,