Learning to Teach As a Rite of Passage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critic-2020-1-Pdf.Pdf

1 1 2 2 3 3 4 HEADQUARTERS OTAGO HARBOUR GOLF 10% student discount. HAIRDRESSING CHALLENGE CENTRE CITY & GEORGE STREET 2-for-1 water hire (paddle boards, single and tandem kayaks). Hire one and get CAPERS CAFE Cut & blow-wave + treatment + Wella take another free for a friend with your home product for $100. 2-for-1 gourmet pancakes. Onecard. 9am Monday – 3pm Friday. Monday to Friday only. Subject to availability/weather. T&C’s SHOSHA apply. CORNERSTONE INK 10% student discount. TATTOO STUDIO Phone SURGEONS 10% discount off any tattoo, not in LUMINO THE 50% off all phone, tablet, laptop, computer conjunction with other special. & console repairs (labour only) or 25% off DENTISTS non-branded cases & accessories. $69 new patient exam (and more...). IRESURRECT subway $20 discount on any repair. UBS ON CAMPUS Buy any six-inch meal-deal and upgrade 10% discount off full-priced items. to a foot-long meal-deal for free. NANDO’S Free regular PERi-PERi Chips (or normal) TM AUTOMOTIVE ZAIBATSU HAIR ART with any main meal purchase. $52 warrant of fitness. Half head foil, cut and style treatment for $139. STIRLING SPORTS GELATO JUNKIE LA PORCHETTA 10% student discount on any full-price items. Receive $1 off double scoop ice cream with Onecard. 10% discount off all food and drinks. ONLY UR’S BEAUTY sal’s pizza EPICDOG PARLOUR One large cheese and one large Free fries with any dog over $10 with Brow and Brazilian Maintenance for $39. pepperoni for $40. Wed 26 Feb only. onecard. CHECK OUT MORE DISCOUNTS AT r1.co.nz/onecard 4 5 CRITIC MERCH NOW AVAILABLE ONLINE criticstore.com 5 6 recently, I’ve noticed the quality of Apology sandwich making in Dunedin has slipped to an incredibly inadequate standard. -

The House of Oojah Audiobooks New Zealand Kiwi Audio CD Mp3

The House of Oojah AudioBooks New Zealand Kiwi Audio CD mp3 - www.Audio-Books.co.nz Murder hearing told of Mob texts . Murder hearing told of Mob texts The Tuesday, 19 August MURDER ACCUSED: Quentin Duff, accused of murdering his partner, during depositions hearing at Porirua District Court. Dog, can you come to the pad? My Mrs is dead. Duff, a patched Mongrel Mob member, is accused of beating his partner of eight years, Bronwyn Aroha Whakaneke, 33, with a metal scaffolding pipe before dumping her outside a bus at the mob headquarters in Waitangirua. The text message, allegedly sent by murder accused Quentin Duff to a Mongrel Mob associate soon after Duff's partner's death, was among several revealed in Porirua District Court yesterday. Duff, who has yet to enter a plea, appeared expressionless in court yesterday for a depositions hearing. Her naked and battered body was found on January 8. Phone records in court revealed that before police were called, Duff text-messaged a Mongrel Mob associate: . It will determine if he will face trial... Duff later text-messaged the same associate from the police station: Dog, I'm examining at a lot of jail now. dog, can you come to the pad? My Mrs is dead. Tell me you didn't bro. The associate replied: I want to believe you didn't do it. Duff replied: I'm in a lot of sh. Getting no response he added: Come on, bark back. at the moment.. Another text from Duff to the associate said: Dog, I'm sorry I just f. -

Drugs, Crime and Statistics a Hangover for Life Prison Needle Exchange Controversy Quit Or Die, You Have Another Choice Contents

Drugs, crime and statistics A hangover for life Prison needle exchange controversy Quit or die, you have another choice Contents matters of substance November 2007 Features Vol 17 No 4 ISSN 1177-200X 02 Cover Story Is alcohol-related brain Mike Webb of the matters of substance is published by the Let’s talk about pot impairment a silent New Zealand Police writes NZ Drug Foundation. All rights reserved. but growing epidemic about a major review of Neither this publication nor any part amongst heavy drinking the Police Act, which is of it may be reproduced without prior permission of the NZ Drug Foundation. New Zealanders? New currently underway, and the research suggests our opportunities this might bring matters of substance invites feedback culture of drunkenness about for harm minimisation and contributions. If you’re interested in may be putting our brains at the frontline of policing. contributing a guest editorial or article, at risk, and most won’t please first contact us: know until it’s too late. [email protected] Marijuana. It’s the most 29 Mythbusters p +64 4 801 6303 widely used and least talked Hard time and about (illicit) recreational Regulars hard numbers Brand development/graphic design drug in New Zealand. In this Origin Design +64 4 801 6644 [email protected] special edition of Matters of 01 The Director’s Cut Substance, we’ve asked Drug Foundation Director interested and interesting NZ Drug Foundation Ross Bell writes about 3rd Floor, 111 Dixon Street people from across the current drug law review in PO Box 3082, Wellington, New Zealand cannabis spectrum to share New Zealand. -

UNIVERSITY of OTAGO ANNUAL REPORT 2007 University of Otago Annual Report

UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO ANNUAL REPORT 2007 UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO ANNUAL REPORT 1 UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO ANNUAL REPORT 2007 UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO CONTACTS UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO Leith Street, Dunedin New Zealand Mail PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand Tel 64 3 479 1100 Fax 64 3 479 8692 Email [email protected] Web www.otago.ac.nz CHRISTCHURCH University of Otago, Christchurch 2 Riccarton Avenue Christchurch, New Zealand Mail PO Box 4345, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Tel 64 3 364 0530 Fax 64 3 364 0525 Email [email protected] WELLINGTON University of Otago, Wellington Mein Street, Newtown Wellington South, New Zealand Mail PO Box 7343, Wellington South 6242, New Zealand Tel 64 4 385 5541 Fax 64 4 389 5725 Email [email protected] University of Otago Stadium Centre Westpac Stadium, Waterloo Quay, Wellington Mail PO Box 400, Wellington 6140, New Zealand Tel 64 4 460 9800 Fax 64 4 460 9801 Email [email protected] AUCKLAND University of Otago Auckland Centre University of Otago House Levels 3 & 4, 385 Queen Street Auckland, New Zealand Mail PO Box 5543, Wellesley Street, Auckland 1141, New Zealand Tel 64 9 373 9700 Fax 64 9 373 9701 Email [email protected] INVERCARGILL College of Education, Southland Campus 100 Nelson Street, Invercargill New Zealand Mail PO Box 886, Invercargill 9840, New Zealand Tel 64 3 211 6724 Fax 64 3 216 1399 Email [email protected] Published May 2008 ISSN 1171-2708 2 VISION A research-led University with an international reputation for excellence. -

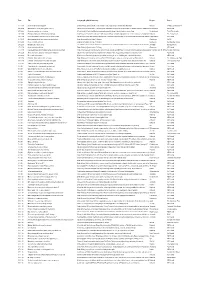

Date Title Category/Key Word Summary Region Paper 22.12.09

Date Title Category/Key Word Summary Region Paper 22.12.09 Public help catches taggers Crime-Waiuku area over/38 yr old refused EBA, $600 fine & 6 mnths disqualification Waiuku Waiuku & Districts Post 24.12.09 Brands succeed by doing good -survey Industry-interest article/64% respondents to poll(6000 consumers) would change to similar product if supportingInternational good cause NZ Herald 25.12.09 Xmas is a mission in recession Mental health-Chch City Mission growing demand for drug & alcohol abuse counselling Christchurch Truth Weekender 26.12.09 Doctors urging care with alcohol and food Health issues-Drs warn to take care with alcohol & food -unwanted pregnancies, vehicle crashes, sexually transmittedNational diseases The Nelson mail 27.12.09 Kerre Woodham: Cheers to bar on "feral" teens Industry-pub/monteiths Brewery Bar/banned <20's/250 youth descend on bar /$2500 damage/pre-load, behaveParaparaumu badly NZ Herald 27.12.09 Man crashes while four times over alcohol limit Drink Driving-40yr old male/1745mcg Gisbourne NZPA 27.12.09 Near-record breath-test Drink Driving-40yr old male/1745mcg Gisbourne Sunday Star Times 27.12.09 Dodging the city clean-up Local Govt-homeless moved on by security guards over Christmas/when there is more incidents of alcohol-fuelledAK violence CBD & mayhem Sunday News 27.12.09 Near-record breath-test Drink Driving-40yr old male/1745mcg Gisbourne NZ Herald 27.12.09 Beware drinkers and bludgers when cycling on life's road Drink Driving-wife on cyclist killed lst yr by70yr old woman gets $400wk on benefit/long -

THE POLITICS ISSUE Issue 27 – 10Th October 2011

THE POLITICS ISSUE Issue 27 – 10th October 2011 Winston Peters Interview | Critic investigates political groups on campus Tea Time at the Milton Hilton | Interviews with OUSA presidential candidates Critic Issue 27 – 1 Critic Issue 27 – 2 Critic – Te Arohi P.O. Box 1436, Dunedin (03) 479 5335 [email protected] www.critic.co.nz Editor: contents Julia Hollingsworth Designer: THE POLITICS ISSUE Andrew Jacombs Issue 27 – 10th October 2011 News Editor: Gregor Whyte News Reporters: Aimee Gulliver, Lozz Holding Editorial 5 Sub Editor: Lisa McGonigle Letters to the Editor 6 Feature Writers: Charlotte Greenfield, Notices 7 Phoebe Harrop, Siobhan Downes, Snippets 8 Joe Stockman Ad Designer: News 10 Karl Mayhew Feature Illustrator: Interrogating the 16 Aimee Gulliver has a chat with the two boys Tom Garden Candidates in line for the OUSA President throne Music Editor: Sam Valentine Tea Time at the Milton 18 Phoebe Harrop discovers there’s more to Film Editor: Hilton prisons than gang bangs and dodgy deals. Sarah Baillie Books Editor: Profile: Garth Badger 21 Sarah Maessen Performance Editor: The Opposite of Apathy 22 Love ‘em or hate ‘em, the political groups on Bronwyn Wallace Campus are a fascinating breed. Food Editor: Niki Lomax The Ring Master 26 Joe Stockman talks to the irrepressible Games Editor: Winston Peters Toby Hills Art Editor: State of the Nation 29 Hana Aoake Poetry Editor: Opinion 31 Tash Smillie Comics Editor: Review 37 Games, Art, Theatre, Music, Books, Food, Film Spencer Hall Child Prodigy: Pick of the Mothras 46 We review the best of the bunch. Basti Menkes And a whole heap of Summer Lovin’ 47 lovely volunteers Poetry 48 Advertising: Kate Kidson, Comics 49 Tim Couch, Dave Eley, Logan Valentine OUSA page 51 For Ad sales contact: (03) 479 5361 [email protected] www.planetmedia.co.nz Critic Issue 27 – 3 ay With Wo Got a W rds? Critic wants you baby.. -

Dunedin | (03) 479 5335 | [email protected] | Critic.Co.Nz

2013/14 WE WANT YOU! obs! Whistler J Product inclusions: $ • Face-to-Face Whistler Blackcomb • Great Resort discounts on 595 interview (Auckland or Queenstown) retail, food & beverage • Staff Housing • Ongoing support from our • Unsuccessful applicants receive Canadian specialists program refund! • In-country support from • Free Season lift pass! Vancouver office (Friendly face on arrival) • Access to our online blog (Connect with work mates pre-departure) • Step-by-Step Visa Assistance • Invitation to our Powder • Meet & Greet Party on pre-departure party Arrival to Canada between Creator : DragonAMondayrt - Friday • 1st Nights Free Accommodation Samesun Hostel Vancouver • Daily Orientations on arrival dragonartz.wordpressto Vancouver.com (Nov only • Arrival Pack - Guide to Living & between Monday - Friday) Working in Canada WHC ™ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ Call 09 973 5913 or go to www.theworkingholidayclub.co.nz E: [email protected] WHC_FPCriticAdvert.indd 1 22/02/13 12:19 PM EDITOR Callum Fredric Issue 02 | March 04, 2013 | critic.co.nz DEPUTY & SUB EDITOR Sam McChesney TECHNCIAL EDITOR Sam Clark DESIGNER Dan Blackball 26 FEATURE WRITER Ines Shennan FEATURE WRITER / BANGING THE EDITOR Maddy Phillipps NEWS FEATURES NEws TEAM Sam McChesney, Zane Pocock, 06 | Hyde Street’s Future 19 | What We Really Mean Claudia Herron, Bella Macdonald in Jeopardy Ines Shennan looks at the hidden agendas behind popular advertisements. SECTION EDITORS Sam McChesney, Basti Menkes, 09 | ODT Invents 19 People Baz McDonald, Josef Alton, Gus Gawn 24 | Lex: Coffee Cowboy 10 | Psycho Man Goes On Ines Shennan interviews enigmatic coffee One-Man Killstreak wizard Lex. CONTRIBUTORS Dennis Larson, John Burton, Greg Hall, Phoebe Harrop, M & G, Glitter Grrl, Dr. -

Kieran Craig Cody

The Contested Terrain of Alcohol Sponsorship of Sport and Social Policy in New Zealand Kieran Craig Cody A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Physical Education (MPhEd) At the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand School of Physical Education Te Kura Mahi-a-korikori Division of Sciences Te Rohi a Ahikaroa University of Otago Te Whare Wananga o Otago ` PO BOX 56, DUNEDIN NEW ZEALAND Abstract This thesis investigates the effects, consequences and contested terrain emerging from alcohol sponsorship of sport in New Zealand. Drawing from the 2010 New Zealand Law Commission report addressing the alcohol issue in New Zealand, this research examined the sport sponsorship debate in relation to one specific recommendation calling for a ban on alcohol sponsorship of sport as part of a three stage process; (1) implementation of regulations based on Loi Evin in France, where sport sponsorship and advertising is banned from sporting arenas and visual mediums; (2) prohibition on alcohol advertising where 10% of participants are under the legal drinking age, including sporting arenas and (3) the eventual complete removal of alcohol sponsorship of sport. Located within a cultural studies framework and employing a qualitative, multi- method approach including document analysis and interviews with key stakeholders, the results highlight the contested terrain of varying interests within particular sectors of New Zealand. Three key findings emerged: (1) alcohol companies have a long history of sponsoring sport and became more powerful following the banning of tobacco sponsorship of sport; (2) the issue of alcohol sponsorship of sport is a contested terrain where particular interest groups (e.g. -

Who's Giving Your Kids Alcohol?

Student drinking: grim and chronic Rap’s bad drug rap Dope and academic doom Eugenics for addicts August 2010 Who’s giving your kids alcohol? Changes to social supply laws are among the most important of the Law Commission’s recommendations. They may help reduce excessive youth drinking and would protect parental rights over who gives alcohol to their children. But in the current political environment, what chance do they have of making it into law? Contents matters of substance August 2010 Features Vol 20 No 3 ISSN 1177-200X 02 Cover Story 14 Experience. Insight. Hope. 10 Opinion matters of substance is published by the The minor issue of social Youth are part NZ Drug Foundation. All rights reserved. supply of the solution Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced without prior Debate about youth drinking permission of the NZ Drug Foundation. has been under the spotlight lately. Sarah Helm argues matters of substance invites feedback that, while youth may be and contributions. If you’re interested in contributing a guest editorial or article, part of the problem, they will please contact us: Two new websites have also play a vital role in [email protected] been launched this month bringing about positive change. p +64 4 801 6303 Young people today face sharing New Zealand stories extreme pressure to drink, about drugs and change. 29 Mythbusters Brand development/graphic design Smoke dope and become one? Origin Design +64 4 801 6644 and under current law, there [email protected] are few restrictions over 22 When drugs and Comparing media hype www.origindesign.co.nz who can supply alcohol to music overlap about cannabis use and minors. -

Tui Motu Interislands Monthly Independent Catholic Magazine September 2011 | $6

Tui Motu InterIslands monthly independent Catholic magazine September 2011 | $6 . editorial sport, earthquakes and elections ugby rules, OK! By the time Sadly they continue . Jim Consedine lives and work together to find a just this edition of Tui Motu points up the resilience of those who common vision . reaches you the Rugby have chosen to remain . Some had Daniel O’Leary gives us a fresh RWorld Cup will dominate sports the means to leave and have done look at the power of personal experi- media worldwide . What has been so; some have gone to relations or ence and the way this opens us to planned for, carefully and some- friends elsewhere . Others remain the Holy Spirit . In vulnerability times with hiccups, has arrived . As a because they want to and can . Many and woundedness, we are open to couch potato rugby spectator, I will have no such options and are strug- the reality of grace — as he puts it, enjoy some of the hoopla and look gling with a situation which is far “…the flavours of God’s presence in forward to revelling in the skill and from ideal . Perseverance, resilience everything that happens to us ”. professionalism of the players lived and courage are words that denote We continue our series on out to the optimum . Mike Riddell’s the endless patience the local people ‘religion and politics’, highlighting article puts the Cup in perspective have shown . matters which may be a stimulus to with wry humour . It all depends Mary Wood’s fairy story high- our thinking and asking questions upon the bounce of the ball! lights the goodness of people who about policy for the forthcoming As a complement to this wit, rise to the occasion of tragedy in general election . -

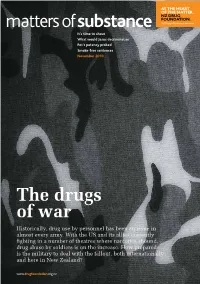

The Drugs of War Historically, Drug Use by Personnel Has Been an Issue in Almost Every Army

It’s time to shout What would Jesus decriminalise Pot’s potency probed Smoke-free sentences November 2010 The drugs of war Historically, drug use by personnel has been an issue in almost every army. With the US and its allies currently fighting in a number of theatres where narcotics abound, drug abuse by soldiers is on the increase. How prepared is the military to deal with the fallout, both internationally and here in New Zealand? Contents matters of substance November 2010 Features Regulars Vol 20 No 4 ISSN 1177-200X 02 Cover Story 01 The Director’s Cut 33 Mythbusters matters of substance is published by the War and drugs Executive Director Ross Bell Cannabis potency NZ Drug Foundation. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part considers public response Police and the media say of it may be reproduced without prior to proposed liquor law ESR tests conducted this permission of the NZ Drug Foundation. changes, and argues there year prove cannabis in is real opportunity to move New Zealand has become matters of substance invites feedback the government further. a whole lot stronger. But and contributions. If you’re interested in contributing a guest editorial or article, just what did these tests please contact us: 18 Guest Editorial examine, and what do the [email protected] Today, more than ever, Compulsory treatment results really mean? p +64 4 801 6303 armies around the world Dutch style are dealing with serious Brand development/graphic design Origin Design +64 4 801 6644 substance abuse problems News [email protected] and the mental health issues www.origindesign.co.nz that result. -

Tuesday, December 22, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI TUESDAY, DECEMBER 22, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PAGE 3 FORGOTTEN VICTIMS ‘OVER THE OF TERROR ATTACK YOUNG AND HOMELESS MOON’ AT MINCE DONATION PAGE 10 PAGE 6 by Mark Peters PEOPLE seen leaping from a launch in the harbour over the weekend have escalated concerns about children and adults jumping into incoming boats’ LIVES AT RISK propeller wash at the harbour boat ramp. This is not an isolated incident, says recreational fisherman Craig Miller. Harbourmaster suggests alternative “But this is the worst we’ve seen. The next worst is other kids who jump off the ice tower. You get eight to 10 kids site for harbour boat ramp jumpers stacked up there waiting to jump off near the boats.” The ramp and pontoon are popular locations for children and adult jumpers but “prop surfers” endanger not only their own lives, but the safety of boaties. The term “prop surfing” refers to the many jumpers who try to leap into a boat’s propeller wash, or jump as close as they can to a boat as it approaches The shipping the ramp. ‘channel is a “We have close calls all the legal road. time,” says Mr Allowing people Miller. “We don’t to swim and want an accident to happen. You jump into the can’t slow or stop harbour is like a four-tonne boat letting them easily.” The boating play on the community do main road not want to be — Craig’ Miller the fun police but neither do boaties want to be responsible for an accident, he says.