Barbosajoseph.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cir Letter-Advent Christmas 2020-ENG.Pdf

15 December 2020 Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, Dear Brothers and Sisters in Saint Benedict and Saint Scholastica, Peace, hope, and divine strength to all Benedictine men and women as we move through these days of Advent toward the celebration of Christ’s Birth. This season which begins the Liturgical Year carries a unique flavor of waiting this year. Quite literally, the whole world awaits a time of blessing: the annual celebration of the Savior’s Birth, the conquest of the pandemic’s invisible yet mighty enemy, a plan for rebuilding the earth’s diminishing resources, and a movement to the “new normal” that will have to unfold before our very eyes. These days of Advent usher us into a time of hope, a hope that can only be fully grounded in the Lord’s love and care, guidance and wisdom, strength, vitality, and promise of Emmanuel, God-with-us. I hope that all Benedictine throughout the world can enter into this holy season with an anticipation that believes that, even though this pandemic has fallen upon the whole world, the Lord will lead us forward. I would like to share some reflections with you about this time. But first, let me give you an update on some matters relating to the Benedictine Order and life at Sant’Anselmo. My own travels and visits to Benedictine communities has been greatly limited because of restrictions related to the Covid-19 virus. However, there have been a few communities with whom I have had some contact. The first week of August, I preached the annual retreat for the monks of Glenstal Abbey in Ireland. -

Missouri River Floodplain from River Mile (RM) 670 South of Decatur, Nebraska to RM 0 at St

Hydrogeomorphic Evaluation of Ecosystem Restoration Options For The Missouri River Floodplain From River Mile (RM) 670 South of Decatur, Nebraska to RM 0 at St. Louis, Missouri Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 Minneapolis, Minnesota Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 15-02 Mickey E. Heitmeyer Joseph L. Bartletti Josh D. Eash December 2015 HYDROGEOMORPHIC EVALUATION OF ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION OPTIONS FOR THE MISSOURI RIVER FLOODPLAIN FROM RIVER MILE (RM) 670 SOUTH OF DECATUR, NEBRASKA TO RM 0 AT ST. LOUIS, MISSOURI Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3 Refuges and Wildlife Minneapolis, Minnesota By: Mickey E. Heitmeyer Greenbrier Wetland Services Advance, MO 63730 Joseph L. Bartletti Prairie Engineers of Illinois, P.C. Springfield, IL 62703 And Josh D. Eash U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 3 Water Resources Branch Bloomington, MN 55437 Greenbrier Wetland Services Report No. 15-02 December 2015 Mickey E. Heitmeyer, PhD Greenbrier Wetland Services Route 2, Box 2735 Advance, MO 63730 www.GreenbrierWetland.com Publication No. 15-02 Suggested citation: Heitmeyer, M. E., J. L. Bartletti, and J. D. Eash. 2015. Hydrogeomorphic evaluation of ecosystem restoration options for the Missouri River Flood- plain from River Mile (RM) 670 south of Decatur, Nebraska to RM 0 at St. Louis, Missouri. Prepared for U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3, Min- neapolis, MN. Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 15-02, Blue Heron Conservation Design and Print- ing LLC, Bloomfield, MO. Photo credits: USACE; http://statehistoricalsocietyofmissouri.org/; Karen Kyle; USFWS http://digitalmedia.fws.gov/cdm/; Cary Aloia This publication printed on recycled paper by ii Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... -

Henry Thoreau’S Journal for 1837 (Æt

HDT WHAT? INDEX 1838 1838 EVENTS OF 1837 General Events of 1838 SPRING JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH SUMMER APRIL MAY JUNE FALL JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER WINTER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Following the death of Jesus Christ there was a period of readjustment that lasted for approximately one million years. –Kurt Vonnegut, THE SIRENS OF TITAN 1838 January February March Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 2 3 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 April May June Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 EVENTS OF 1839 HDT WHAT? INDEX 1838 1838 July August September Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 1 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 October November December Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 1 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Read Henry Thoreau’s Journal for 1837 (æt. -

Conception Seminary College Catalog

ISSUE NO. 124 2016–2018 CONCEPTION SEMINARY COLLEGE CATALOG A community of faith and learning dedicated to the preparation of candidates for the ordained ministry in the Roman Catholic Church ESTABLISHED IN 1886 BY THE BENEDICTINE MONKS OF CONCEPTION ABBEY CONCEPTION, MISSOURI 64433 ACCREDITED BY The Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association contents of Colleges and Secondary Schools Directory . 4 Purpose . 5 Historical Sketch . 9 Campus Map . 12 Campus & Facilities . 13 Student Life . 17 Seminary Programs . 19 MEMBER OF National Association of College Seminaries Admission . 31 American Association of Higher Education Expenses & Financial Aid . 39 American Council on Education Academic Information . 43 National Catholic Educational Association Degree Requirements . .. 55 American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers Divisional & Departmental Goals . 59 Courses of Instruction . 62 Approved for veterans’ educational benefits under Section 1775 of Title 38 of the United States Code Alumni Association . 79 Administration . 81 Conception Seminary College does not discriminate Faculty . 83 on the basis of race, color, national background, or ethnic origin Index . 86 in the conduct of any of its programs and policies. Location . 96 The information in this catalog is current as of the time of publication but is subject to change without notice. The on-line catalog is the official catalog of the college and may differ from the printed version. The on-line catalog can be viewed at the following link: http://www.conception.edu/csc/college-catalogs. The catalog is for information only and is not a contract between Conception Seminary College and any person or entity. on the cover: Conception Seminary College’s crest and motto Caritas Christi Urget Nos — The Love of Christ Impels Us contents 2 www.conception.edu Conception Seminary College 2016–2018 3 purpose directory AREA CODE 660 Conception Seminary College . -

Clinton County in Pictures Would Not Be Completed Without Mention of the Part Harold Played in Its Pioduction

CLINTON COUNTY PICTURES A PICTORIAL REVIEW OF CLINTON COUNTY COMMEM ORATING ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF PROGRESS. FOREWORD In attempting to present the history of Clinton county in picture and story the editor realized that he was undertaking a task of gigantic proportions that would require much time and labor as well as a large financial outlay to complete. But had we known as well the magnitude of that task, and its cost, as we know it now, the work would never have been attempted. But once begun, regardless of the cost or the labor involved we determined to see it through. We did not begin the work with any idea of large profit; if it paid its way and a small compensation for the labor involved we would be satisfied. Having lived in Clinton and being the editor of one of its newspapers for a number of years; we felt some pride in our county and wished to publish a volume that would be the best representation of the county that had ever appeared in print. From the beginning it was our desire and intention to publish a history different from anything heretofore produced. We have followed the modern trend of using pictures with short narrative, descriptive or biographical material of each to tell the story. We have tried to represent Clinton County at its best; to give an attractive presentation of our county's business, educational and social life. The book is ar ranged in sections, the first section being about the county as a whole. This is fol lowed by sections on the towns including the farm homes around them. -

The Vox Populi Is the Vox Dei: American Localism and the Mormon Expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2012 The Vox Populi Is the Vox Dei: American Localism and the Mormon Expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri Matthew Lund Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Lund, Matthew, "The Vox Populi Is the Vox Dei: American Localism and the Mormon Expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri" (2012). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1240. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1240 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VOX POPULI IS THE VOX DEI : AMERICAN LOCALISM AND THE MORMON EXPULSION FROM JACKSON COUNTY, MISSOURI by Matthew Lund A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: __________________________ __________________________ Philip Barlow Daniel J. McInerney Major Professor Committee Member __________________________ __________________________ Anthony A. Peacock Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2012 ii Copyright © Matthew Lund 2012 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The Vox Populi Is the Vox Dei : American Localism and the Mormon Expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri by Matthew Lund, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2012 Major Professor: Philip Barlow Department: History In 1833, enraged vigilantes expelled 1,200 Mormons from Jackson County, Missouri, setting a precedent for a later expulsion of Mormons from the state, changing the course of Mormon history, and enacting in microcosm a battle over the ultimate source of authority in America’s early democratic society. -

Pressespiegel

Pressespiegel Kanton verzichtet auf Sparübung Der Beitrag des Kantons Obwalden an die Stiftsschule bleibt unverändert. Es gehe darum, diese zu erhalten, sagt Regierungsrat Schäli. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 12.7.2019, Seite 25“ Regierung stellt Gymnasien gutes Zeugnis aus Sechs von zehn erfolgreichen Maturanden der Obwaldner Gymnasien machen später einen Bachelorabschluss. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 10.9.2019, Seite 24“ Stiftsschule erhält neuen Rektor Der Rektor von Engelberg möchte nur noch Lehrer sein. Nun übernimmt wieder ein Mönch die Leitung. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 10.9.2019, Seite 25“ The sky ins‘t the limit Glaube und Wissen liegen an der Stiftsschule des Benediktinerklosters Engelberg nahe beieinander. Seit 1120 werden hier junge Menschen fürs Leben geschult. Ganz nahe am Himmel. Und immer im Kontext der Zeit. „Swiss Magazin, Ausgabe November 2019, Seite 94-98“ Mammutprojekt zum Jubiläum Auf eigene Art bringt das Kollegitheater Engelberg ein Stück Kloster-, Schul- und Theatergeschichte auf die Bühne. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 7.2.2020, Seite 25“ Er untersucht die Vergangenheit seiner Schule In seiner Maturaarbeit befasste sich der Engelberger Pietro Parodi mit Flüchtlingen im Zweiten Weltkrieg. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 28.2.2020, Seite 27“ Smartphone-Schäden lassen aufmerken Welche Auswirkungen haben Smartphones auf den jugendlichen Körper? Dem ging Enya Steffen in ihrer Maturaarbeit nach. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 3.3.2020, Seite 23“ Leere Zimmer — auch im Internat Die Privatschulen in Obwalden tragen als Folge der Coronakrise auch das Risiko des Verlusts von Geldern. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 3.4.2020, Seite 19“ Gymnasiasten üben ihre Selbständigkeit Wie in den meisten Schulen steht auch in der Stiftsschule Engelberg der Fernunterricht im Fokus. „Obwaldner Zeitung, 22.4.2020, Seite 15“ 25 Freitag, 12. -

Hawksbury Resource Guide 19JAN2021

Your Neighborhood Resource Guide Welcome to Hawksbury! We would like to take a moment to congratulate and welcome you on the purchase of your new home. The Hawksbury neighborhood has continued to grow and we are excited to have you as a part of it. Be sure to join eNeighbors message board and community website run by FirstService Residential, Inc. for official community communications and the Hawksbury Homeowner’s Association Facebook Page to stay up to date with the latest happenings in the neighborhood. –Your Hawksbury Neighborhood Welcome Committee Community Amenities/Activities: Pool – Open Memorial Day – Labor Day Walking Trail – Open Year Round Food Trucks – Be on the lookout for food trucks in the summertime Social Gatherings – Be on the lookout for summer BBQs and social gatherings Neighborhood Workouts / Walks – Join your neighbors for early morning outdoor workouts or evening wine walks Turkey Trot – Join the neighborhood for a 5K the morning of Thanksgiving Holidays – Join the neighborhood Halloween costume party and the holiday lighting competition Walk-Tails - Ladies walking group (summer evenings) Community HOA & Committee Contacts: HOA Property Manager FirstService Residential, Inc. 11125 NW Ambassador Dr., Ste 200, Kansas City, MO 64153 (816) 414-5300 Contact FirstService Residential, Inc. to get your pool key. HOA Board Kevin Poos – President; [email protected] Jake Boxberger – Vice President; [email protected] Jim Caniglia – Treasurer; [email protected] Robert Risner – Secretary; [email protected] -

Lida W. Pyles, Whose Pa- Pers Are Archived at the Univesity of Arkansas

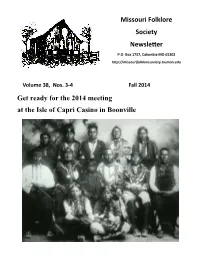

Missouri Folklore Society Newsletter P.O. Box 1757, Columbia MO 65202 http://missourifolkloresociety.truman.edu Volume 38, Nos. 3-4 Fall 2014 Get ready for the 2014 meeting at the Isle of Capri Casino in Boonville "Native Nations, Boonslick Traditions” is our theme. We welcome any subject ranging from Native history and traditions (such as the atlatl demo or presenta- tions about the Missourias, Osage, Ioway, Sac and Fox, etc.) to any subject rele- vant to mid-Missouri, such as Boonslick quilting traditions, storytelling, railroad lore, black folklore and folk art, German presence in mid-Missouri, etc. We have some interesting speakers lined up, including Greg Olson talking about the Ioways, Mike Dickey speaking about the Missourias and perhaps the Osage as well, Mary Barile presenting a talk on Boonslick ghost stories, Ralph Duren presenting a very animated demo of bird calls and animal calls. We will hopeful- ly be able to tour the DAR headquarters in Boonville, and a few other historically significant homes as well. This will all be finalized in August. The meeting will be held at the Isle of Capri Hotel and Casino in Boonville. Isle hotel room prices are $69 for Thursday and $109 for Friday. They will hold a block of rooms, but if those are all sold, those prices will still be available. They release the block 14 days before the event. I have included the phone number on the registration form (see the last page of this newsletter), and that is the general number for the Isle as well. I have put an Oct. -

Abbot Ignatius Conrad March 13Th Is the Anniversary of the Death of Abbot Ignatius Conrad, the First Abbot of Our Mon- Astery

Abbot Ignatius Conrad March 13th is the anniversary of the death of Abbot Ignatius Conrad, the first abbot of our mon- astery. Nicholas Conrad was born on November 15, 1846, in the town of Au, Canton Aargau, Switzer- land. In a family of 12, Nicholas had 10 brothers and one sister. After completing his primary education in the schools of his canton, he continued his studies at Engelberg Abbey. Later, he studied philosophy at the Einsiedeln Abbey where he professed his vows as a monk of Einsiedeln on August 30, 1868, receiving the name Ignatius Loyola. Bishop Kaspar Willi of the Swiss Diocese of Chur ordained him a priest on September 17, 1871. After his priestly ordination, Father Ignatius served the community of Einsiedeln as a teacher of Latin in the Abbey School from 1872 to 1875. Father Ignatius was one of five brothers who be- came priests, four of them joining the Benedictine Order. The eldest, Father Frowin Conrad, a monk of Engelberg Abbey, had been sent to the United States in 1872, in order to establish a Benedictine mission house in northwestern Missouri. Two other brothers, who became Fathers Pius and John, had associated themselves with him. The abbot of Einsiedeln agreed to send Father Ignatius to the United States at the end of the 1875 school year, assigning him to St. Meinrad's Abbey in Indiana, with the understanding that he should be assigned from there to lend assistance to the monks at "New Engelberg" mission house in Missouri. After gaining some proficiency in writing and speaking English, Father Ignatius began his mis- sionary work in Nodaway, Worthy, Gentry, and other northwestern counties of Missouri. -

Kansas City and the Great Western Migration, 1840-1865

SEIZING THE ELEPHANT: KANSAS CITY AND THE GREAT WESTERN MIGRATION, 1840-1865 ___________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________ By DARIN TUCK John H. Wigger JULY 2018 © Copyright by Darin Tuck 2018 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled SEIZING THE ELEPHANT: KANSAS CITY AND THE GREAT WESTERN MIGRATION, 1840-1865 Presented by Darin Tuck, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________ Professor John Wigger __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Catherine Rymph __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Robert Smale __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Rebecca Meisenbach __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Carli Conklin To my mother and father, Ronald and Lynn Tuck My inspiration ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was only possible because of the financial and scholarly support of the National Park Service’s National Trails Intermountain Region office. Frank Norris in particular served as encourager, editor, and sage throughout -

Sediment Transport and Deposition in the Lower Missouri River During the 2011 Flood

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sediment Transport and Deposition in the Lower Missouri River During the 2011 Flood Chapter F of 2011 Floods of the Central United States Professional Paper 1798–F U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front cover. Top photograph: View of flooding from Nebraska City, Nebraska, looking east across the Missouri River, August 2, 2011. Photograph by Robert Swanson, U.S. Geological Survey. Right photograph: USGS scientist collecting a sediment sample from the Missouri River at Sioux City, Iowa, September 16, 2011. Photograph by Ryan Tompkins, U.S. Geological Survey. Back cover. Sand from the 2011 flood on the flood plain in northwestern Missouri, September 22, 2012. Photograph by Robert Jacobson, U.S. Geological Survey. Sediment Transport and Deposition in the Lower Missouri River During the 2011 Flood By Jason S. Alexander, Robert B. Jacobson, and David L. Rus Chapter F of 2011 Floods of the Central United States In cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Professional Paper 1798–F U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2013 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.