The War of the Polish Succession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Show Publication Content!

PAMIĘTNIKI SEWERYNA BUKARA z rękopismu po raz pierwszy ogłoszone. DREZNO. DRUKIEM I NAKŁADEM J. I. KRASZEWSKIEGO. 1871. 1000174150 0 (JAtCS V łubłjn Tych kilkanaście lat pamiętni ej szych młodośći mojej, Wspomnienia starego człowieka w upominku dla synów przekazuję. Jours heureux, teins lointain, mais jamais oublié. Où tout ce dont le charme intéresse à la vie. Egayait mes destins ignorés de l'envie. (Marie Joseph Chenier.)., Zaczęto d. 28. Czerwca 1845 r. Od lat kilku już ciągłe od was, kochani syno wie, żądania odbierając, abym napisał pamiętniki moje, zawsze wymawiałem się od tego, z pobudek następu jących. Naprzód, iż, podług mnie, ten tylko powinien zajmować się tego rodzaju opisami, kto, czyli sam bez pośrednio, czy też wpływając do czynności znakomi tych w kraju ludzi, dał się zaszczytnie poznać i do konywał rzeczy wartych pamięci. Powtóre : iż doszedł szy już późnego wieku, nie dałem sobie nigdy pracy notowania okoliczności i spraw, których świadkiem by łem, lub do których wpływałem. Trudno więc przy chodzi pozbierać w myśli kilkadziesiąt-letnie fakta. Lecz tłumaczenia moje nie zdołały zaspokoić was, i mocno upieracie się i naglicie na mnie o te niesz częśliwe pamiętniki. — To mi właśnie przypomniało, com wyczytał w opisie jakiegoś podróżującego: że w Chinach ludzie, którzy szukają wsparcia pieniężnego, mają zawsze w kieszeni instrumencik dęty — rodzaj piszczałek, który wrzaskliwy i przerażający głos wy- VIII daje. Postrzegłszy więc w swojéj drodze człowieka, którego powierzchowność obiecuje im zyskowną dona- tywę, zbliżają się do niego, idą za nim krok w krok i dmą w swój instrumencik tak silnie i tak długo, że rad nie rad, dla spokojności swojéj, obdarzyć ich musi. -

LP NVK Anhang (PDF, 7.39

Landschaftsplan 2030 Nachbarschaftsverband Karlsruhe 30.11.2019 ANHANG HHP HAGE+HOPPENSTEDT PARTNER INHALT 1 ANHANG ZU KAP. 2.1 – DER RAUM ........................................................... 1 1.1 Schutzgebiete ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Naturschutzgebiete ................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Landschaftsschutzgebiete ........................................................................ 2 1.1.3 Wasserschutzgebiete .................................................................................. 4 1.1.4 Überschwemmungsgebiete ...................................................................... 5 1.1.5 Waldschutzgebiete ...................................................................................... 5 1.1.6 Naturdenkmale – Einzelgebilde ................................................................ 6 1.1.7 Flächenhaftes Naturdenkmal .................................................................... 10 1.1.8 Schutzgebiete NATURA 2000 .................................................................... 11 1.1.8.1 FFH – Gebiete 11 1.1.8.2 Vogelschutzgebiete (SPA-Gebiete) 12 2 ANHANG ZU KAP. 2.2 – GESUNDHEIT UND WOHLBEFINDEN DER MENSCHEN ..................... 13 3 ANHANG ZU KAP. 2.4 - LANDSCHAFT ..................................................... 16 3.1 Landschaftsbeurteilung ............................................................................................... -

The Stolen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in World War Ii?

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 1999 The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? Barbara Tyler Cleveland State University, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Publisher's Statement Copyright permission granted by the Rutgers University Law Journal. Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Original Citation Barbara Tyler, The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? 30 Rutgers Law Journal 441 (1999) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 30 Rutgers L.J. 441 1998-1999 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon May 21 10:04:33 2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0277-318X THE STOLEN MUSEUM: HAVE UNITED STATES ART MUSEUMS BECOME INADVERTENT FENCES FOR STOLEN ART WORKS LOOTED BY THE NAZIS IN WORLD WAR II? BarbaraJ. -

Richard & the Percys

s Richard III Society, Inc. Volume XXV No. 3 Fall, 2000 — Susan Dexter Richard & The Percys Register Staff EDITOR: Carole M. Rike 4702 Dryades St. • New Orleans, LA 70115 (504) 897-9673 FAX (504) 897-0125 • e-mail: [email protected] ©2000 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be RICARDIAN READING EDITOR: Myrna Smith reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means — mechanical, Rt. 1 Box 232B • Hooks, TX 75561 electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval — without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by (903) 547-6609 • FAX: (903) 628-2658 members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is e-mail: [email protected] published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $18.00 ARTIST: Susan Dexter annually. 1510 Delaware Avenue • New Castle, PA 16105-2674 e-mail: [email protected] The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT — YORKSHIRE allowed by law. Geoffrey Richardson Dues are $30 annually for U.S. Addresses; $35 for international. Each additional family member is $5. Members of the American Society are also members of the English Society. Members also In This Issue receive the English publications. All Society publications and items for sale may be purchased either direct at the U.K. Member’s price, or via the American Branch when available. Papers may be borrowed Editorial License, Carole Rike . 3 from the English Librarian, but books are not sent overseas. When a Richard & The Percys, Sandra Worth . -

Elements of Recovery

ELEMENTS OF RECOVERY An Inventory of Upslope Sources of Sedimentation in the Mattole River Watershed with Rehabilitation Prescriptions and Additional Information for Erosion Control Prioritization Prepared for the California Department of Fish and Game by the Mattole Restoration Council P.O. Box 160 Petrolia, CA 95558 December 1989 ELEMENTS OF RECOVERY Erosion is as common an aspect of life in the Coast Range as Pacific sunsets. As the mountains rise up out of the soft ocean bottom, a tenuous and fluid equilibrium is established -- most of each year's uplift is washed or shaken back into the sea. An inch of soil which took a hundred years to build can wash away in a single storm unless held in place by grasses, shrubs, and trees. The streams and rivers are conduits for all this material on its way downhill. Yet under conditions of equilibrium, no more sediment enters the stream than can be easily stored or quickly transported through the system. The Mattole in prehis- toric times was able to move thousands of yards of sediment each year and still be called "clear water," the meaning of the word Mattole in the native tongue. To give an idea of how much ma- terial is moving through the fluvial system, one geologist has estimated that Kings Peak would be 40,000 feet high were it not for this "background" erosion. It doesn't take much to create a disturbance in such a deli- cately balanced system. The erosive power of water increases in proportion to the square of its volume. A midslope road poorly placed, or built on the cheap, or lazily maintained, or aban- doned, can divert large volumes of water from one drainage to another, or onto a slope unarmored by large rock or tree roots. -

Baccalaureate to Be Sunday Night Alb P.M

.. ---.,..----~ ~ . ...~ . ,... "'l " GENUIN'E ~ JOHN PLAINS GRAIN & F'ARM SUPPLY DEERE AIIERNATHY.TEXAS ~ FOR All YOU~ FARMING NEEDS PARTS " }I ·";;~";~2;··"· VOLUME 57 Joe Thompson Implement Co. THURSDAY, MAY 18, 1978 Lubbock County NUMBER 24 Abernathy, r,' .a" 298-2541 lubbock Phone '62 · 1038 E2__ .--- Baccalaureate 1978~ To Be Sunday Night AlB P.M. BACCALAUREATE Sunday, May 21, 1978 -- 8:00 p.m. PROCESSIONAL "Processional March"-------------·-AHS Band (Audience Seated) INVOCA TI ON ________ . Rev. Rosswell Brunner (Minister, Church of the Nazarene) HYMN -----------------------Congregation ( Clinton Barrick ) SERMON----------------- Dr. Jacky Newton ( Minister, First Baptist Church) ANNOUNCEMENTS---------Dr. Delwin Webb (Superintendent of Schools) BENED ICTI ON -------------Cond B" " I (Minister, Church of Christ) Y lings ey RECES S IONAL--------------- ____ AHS Band (Slavonic Folk Suite, Second M:Jv't ) AJHS BANDS WIN 1ST. DIVISIONS The Abernathy 6th ~ ra de T he. judges for the ba nd beginning ba nd P_l l ticipa t €, d conte ~ t wert>, Bill 'A ' oo~ ';n CODtrc;t <iaturdav , M 1' " ~ ~ froTn Se :.4.g r av~ ~ , Le <. H f> Ross at Floydada. The band from Pete rs burg a nJ Roger received first divisions in Edw a rd!; from lubbock. both con~rt and sight!\' ad Both bands will perform iog e vents. The band, Dum Friday ni~ht, May 19 at the bering 58 students, played Antelope Band Program's "A-roving" a nd "Gonna Fly Annua l Spring Concert at Now",the theme of "Rocky" 7:15in the ·\bern a thy for the ir eonce rt se Ie ctions. Auditorium. The .~ bernathy Jr. High Band comretrd at the- ~a me Sunshine Group Teachers Honored At Ann ual Appreciation Banquet May II BAND CONCERT SET PUBLIC INVITED RECE IVE DEGREES contest. -

Jordan and the World Trading System: a Case Study for Arab Countries Bashar Hikmet Malkawi the American University Washington College of Law

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law SJD Dissertation Abstracts Student Works 1-1-2006 Jordan and the World Trading System: A Case Study for Arab Countries Bashar Hikmet Malkawi The American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/stu_sjd_abstracts Part of the Economics Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Malkawi B. Jordan and the World Trading System: A Case Study for Arab Countries [S.J.D. dissertation]. United States -- District of Columbia: The American University; 2006. Available from: Dissertations & Theses @ American University - WRLC. Accessed [date], Publication Number: AAT 3351149. [AMA] This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in SJD Dissertation Abstracts by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JORDAN AND THE WORLD TRADING SYSTEM A CASE STUDY FOR ARAB COUNTRIES By Bashar Hikmet Malkawi Submitted to the Faculty of the Washington College of Law of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Juric] Dean of the Washington College of Law Date / 2005 American University 2 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UMI Number: 3351149 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two

The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two: Personal Accounts from Hitler’s Elite Soldiers By Terry Goldsworthy The Waffen-SS in Allied Hands Volume Two: Personal Accounts from Hitler’s Elite Soldiers By Terry Goldsworthy This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Terry Goldsworthy All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0858-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0858-3 All photographs courtesy of the US National Archives (NARA), Bundesarchiv and the Imperial War Museum. Cover photo – An SS-Panzergrenadier advances during the Ardennes Offensive, 1944. (German military photo, captured by U.S. military photo no. HD-SN-99-02729; NARA file no. 111-SC-197561). For Mandy, Hayley and Liam. CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... xiii VOLUME ONE Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 The rationale for the study of the Waffen-SS ........................................ 1 Sources of information for this book .................................................... -

Changes in Sediment Flux and Storage Within a Fluvial System: Some

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 17, 3321–3334 (2003) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hyp.1389 Changes in sediment flux and storage within a fluvial system: some examples from the Rhine catchment Andreas Lang,1* Hans-Rudolf Bork,2 Rudiger¨ Mackel,¨ 3 Nicholas Preston,1 Jurgen¨ Wunderlich4 and Richard Dikau1 1 Geographisches Institut, Universit¨at Bonn, Meckenheimer Allee 166, D-53115 Bonn, Germany 2 Okologie-Zentrum¨ Kiel, Christian-Albrechts-Universit¨at zu Kiel, Schauenburger Str. 112, D-24118 Kiel, Germany 3 Institut f¨ur Physische Geographie, Albert-Ludwigs-Universit¨at, Werderring 4, D-79085 Freiburg, Germany 4 Institut f¨ur Physische Geographie, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universit¨at, D-60054 Frankfurt, Germany Abstract: The Rhine river system can look back on a long history of human impact. Whereas significant anthropogenic changes to the river channel started only 200 years ago, the impacts of land use have been felt for more than 7500 years. Here, we review results from several case studies and show how land-use change and climate impacts have transformed the fluvial system. We focus on changes in sediment delivery pathways and slope–channel coupling, and show that these vary in time and depend on the magnitude of a rainfall event. These changes must be accounted for when trying to use sediments as archives of land-use change and climatic impacts on fluvial systems. For example, human impact is recorded in slope deposits only as long as rainfall intensity and runoff generation do not exceed the threshold for gullying. Similarly, climatic impacts are only recorded in alluvium when both the landscape is rendered sensitive by human activities (e.g. -

Sfoglia On-Line

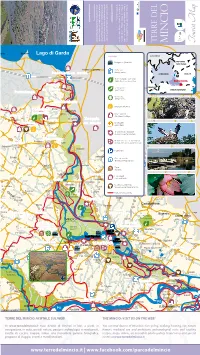

www.terredelmincio.it and good living. routes filled with good food, and historical, as cultural well as natural of “surprises”, chance An with a great area within the boundaries of the Mincio Regional Park. of Lombardy, corner up the eastern del Mincio take the Terre Garda and the Po, between Lake Lying www.terredelmincio.it buon vivere. itinerari, sapori, storia, cultura, di natura, “sorprese”: di ad alta densità Un’area del Mincio. del Parco nei confiniil lembo orientale della Lombardia, sono del Mincio” “Terre le e il Po il lago di Garda Tra Negrar Sant'Ambrogio di V. Botticino Prevalle Soiano del Lago UNIONE EUROPEA Brescia Nuvolento Tregnago S. Giovanni Ilarione Nuvolera Calvagese della Riviera Cavaion Veronese Moniga del Garda Roncadelle Travagliato Rezzato Bedizzole Padenghe Sul Garda S. Pietro in Cariano Brescia centro Mazzano Berlingo Pastrengo Mezzane di Sotto Ronc‡ TERRE DEL Castel Mella Pescantina MINCIO Cazzano di Tramigna S. Zeno Naviglio Montecchia di Crosara Flero Lograto Illasi Borgosatollo Maclodio Brescia est Desenzano del Garda Sirmione Lago di Garda Castenedolo Bussolengo A4 LEGENDA SVIZZERA Lonato Poncarale Calcinato Navigazione | Boat Trips TRENTINO Montebello ALTO ADIGE Verona Brandico Azzano Mella Lavagno Capriano del Colle Soave Monteforte d'Alpone Mairano Montirone Castelnuovo del Garda Stazione FS Verona nord Desenzano Railway Station Sirmione Peschiera del Garda LOMBARDIA VENETO Longhena Colognola ai Colli SonaRiserve Naturali o Aree Verdi Bagnolo Mella Dolci S. Martino Buon Albergo Peschiera Nature Reserves or Green Areas MANTOVA Ponti Soave PIEMONTE A4 Dello Montichiari Centro Cicogne Caldiero Sommacampagna sul Mincio Storks Center EMILIA ROMAGNA Verona est Pozzolengo S. Bonifacio Barbariga Ghedi Astore Castiglione Centri Visita Visitor Centers delle Stiviere A22 Monzambano Offlaga Infopoint | Info Points Belfiore Perini Castellaro Arcole Grole Lagusello MINCIO S. -

Maurice-Quentin De La Tour

Neil Jeffares, Maurice-Quentin de La Tour Saint-Quentin 5.IX.1704–16/17.II.1788 This Essay is central to the La Tour fascicles in the online Dictionary which IV. CRITICAL FORTUNE 38 are indexed and introduced here. The work catalogue is divided into the IV.1 The vogue for pastel 38 following sections: IV.2 Responses to La Tour at the salons 38 • Part I: Autoportraits IV.3 Contemporary reputation 39 • Part II: Named sitters A–D IV.4 Posthumous reputation 39 • Part III: Named sitters E–L IV.5 Prices since 1800 42 • General references etc. 43 Part IV: Named sitters M–Q • Part V: Named sitters R–Z AURICE-QUENTIN DE LA TOUR was the most • Part VI: Unidentified sitters important pastellist of the eighteenth century. Follow the hyperlinks for other parts of this work available online: M Matisse bracketed him with Rembrandt among • Chronological table of documents relating to La Tour portraitists.1 “Célèbre par son talent & par son esprit”2 – • Contemporary biographies of La Tour known as an eccentric and wit as well as a genius, La Tour • Tropes in La Tour biographies had a keen sense of the importance of the great artist in • Besnard & Wildenstein concordance society which would shock no one today. But in terms of • Genealogy sheer technical bravura, it is difficult to envisage anything to match the enormous pastels of the président de Rieux J.46.2722 Contents of this essay or of Mme de Pompadour J.46.2541.3 The former, exhibited in the Salon of 1741, stunned the critics with its achievement: 3 I. -

Fortification Renaissance: the Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne

FORTIFICATION RENAISSANCE: THE ROMAN ORIGINS OF THE TRACE ITALIENNE Robert T. Vigus Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: Guy Chet, Committee Co-Chair Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Co-Chair Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Vigus, Robert T. Fortification Renaissance: The Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne. Master of Arts (History), May 2013, pp.71, 35 illustrations, bibliography, 67 titles. The Military Revolution thesis posited by Michael Roberts and expanded upon by Geoffrey Parker places the trace italienne style of fortification of the early modern period as something that is a novel creation, borne out of the minds of Renaissance geniuses. Research shows, however, that the key component of the trace italienne, the angled bastion, has its roots in Greek and Roman writing, and in extant constructions by Roman and Byzantine engineers. The angled bastion of the trace italienne was yet another aspect of the resurgent Greek and Roman culture characteristic of the Renaissance along with the traditions of medicine, mathematics, and science. The writings of the ancients were bolstered by physical examples located in important trading and pilgrimage routes. Furthermore, the geometric layout of the trace italienne stems from Ottoman fortifications that preceded it by at least two hundred years. The Renaissance geniuses combined ancient bastion designs with eastern geometry to match a burgeoning threat in the rising power of the siege cannon. Copyright 2013 by Robert T. Vigus ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and encouragement of many people.