Two Interesting Events in Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sarfatti and Venturi, Two Italian Art Critics in the Threads of Modern Argentinian Art

MODERNIDADE LATINA Os Italianos e os Centros do Modernismo Latino-americano Sarfatti and Venturi, Two Italian Art Critics in the Threads of Modern Argentinian Art Cristina Rossi Introduction Margherita Sarfatti and Lionello Venturi were two Italian critics who had an important role in the Argentinian art context by mid-20th Century. Venturi was only two years younger than Sarfatti and both died in 1961. In Italy, both of them promoted groups of modern artists, even though their aesthetic poetics were divergent, such as their opinions towards the official Mussolini´s politics. Our job will seek to redraw their action within the tension of the artistic field regarding the notion proposed by Pierre Bourdieu, i.e., taking into consider- ation the complex structure as a system of relations in a permanent state of dispute1. However, this paper will not review the performance of Sarfatti and Venturi towards the cultural policies in Italy, but its proposal is to reintegrate their figures – and their aesthetical and political positions – within the interplay of forces in the Argentinian rich cultural fabric, bearing in mind the strategies that were implemented by the local agents with those who they interacted with. Sarfatti and Venturi in Mussolini´s political environment Born into a Jewish Venetian family in 1883, Margherita Grassini got married to the lawyer Cesare Sarfatti and in 1909 moved to Milan, where she started her career as an art critic. Convinced that Milan could achieve a central role in the Italian culture – together with the Jewish gallerist Lino Pesaro – in 1922 Sarfatti promoted the group Novecento. -

Rethinking Savoldo's Magdalenes

Rethinking Savoldo’s Magdalenes: A “Muddle of the Maries”?1 Charlotte Nichols The luminously veiled women in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s four Magdalene paintings—one of which resides at the Getty Museum—have consistently been identified by scholars as Mary Magdalene near Christ’s tomb on Easter morning. Yet these physically and emotionally self- contained figures are atypical representations of her in the early Cinquecento, when she is most often seen either as an exuberant observer of the Resurrection in scenes of the Noli me tangere or as a worldly penitent in half-length. A reconsideration of the pictures in connection with myriad early Christian, Byzantine, and Italian accounts of the Passion and devotional imagery suggests that Savoldo responded in an inventive way to a millennium-old discussion about the roles of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene as the first witnesses of the risen Christ. The design, color, and positioning of the veil, which dominates the painted surface of the respective Magdalenes, encode layers of meaning explicated by textual and visual comparison; taken together they allow an alternate Marian interpretation of the presumed Magdalene figure’s biblical identity. At the expense of iconic clarity, the painter whom Giorgio Vasari described as “capriccioso e sofistico” appears to have created a multivalent image precisely in order to communicate the conflicting accounts in sacred and hagiographic texts, as well as the intellectual appeal of deliberately ambiguous, at times aporetic subject matter to northern Italian patrons in the sixteenth century.2 The Magdalenes: description, provenance, and subject The format of Savoldo’s Magdalenes is arresting, dominated by a silken waterfall of fabric that communicates both protective enclosure and luxuriant tactility (Figs. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Renaissance Art and Architecture

Renaissance Art and Architecture from the libraries of Professor Craig Hugh Smyth late Director of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; Director, I Tatti, Florence; Ph.D., Princeton University & Professor Robert Munman Associate Professor Emeritus of the University of Illinois; Ph.D., Harvard University 2552 titles in circa 3000 physical volumes Craig Hugh Smyth Craig Hugh Smyth, 91, Dies; Renaissance Art Historian By ROJA HEYDARPOUR Published: January 1, 2007 Craig Hugh Smyth, an art historian who drew attention to the importance of conservation and the recovery of purloined art and cultural objects, died on Dec. 22 in Englewood, N.J. He was 91 and lived in Cresskill, N.J. The New York Times, 1964 Craig Hugh Smyth The cause was a heart attack, his daughter, Alexandra, said. Mr. Smyth led the first academic program in conservation in the United States in 1960 as the director of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Long before he began his academic career, he worked in the recovery of stolen art. After the defeat of Germany in World War II, Mr. Smyth was made director of the Munich Central Collecting Point, set up by the Allies for works that they retrieved. There, he received art and cultural relics confiscated by the Nazis, cared for them and tried to return them to their owners or their countries of origin. He served as a lieutenant in the United States Naval Reserve during the war, and the art job was part of his military service. Upon returning from Germany in 1946, he lectured at the Frick Collection and, in 1949, was awarded a Fulbright research fellowship, which took him to Florence, Italy. -

Renaissance History Through His Humanist Accomplishments

3-79 A / /vO.7Y HUMANISM AND THE ARTIST RAPHAEL: A VIEW OF RENAISSANCE HISTORY THROUGH HIS HUMANIST ACCOMPLISHMENTS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science By Douglas W. Miller, B.A., M.S. Denton, Texas August, 1991 Miller, Douglas W., Humanism and the Artist Raphael: A View of Renaissance History Through His Humanist Accomplishments. Master of Science (History), August, 1991, 217 pp., 56 illustrations, bibliography, 43 titles. This thesis advances the name of Raphael Santi, the High Renaissance artist, to be included among the famous and highly esteemed Humanists of the Renaissance period. While the artistic creativity of the Renaissance is widely recognized, the creators have traditionally been viewed as mere craftsmen. In the case of Raphael Santi, his skills as a painter have proven to be a timeless medium for the immortalizing of the elevated thinking and turbulent challenges of the time period. His interests outside of painting, including archaeology and architecture, also offer strong testimony of his Humanist background and pursuits. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to gratefully acknowledge the kind and loving support (and patience) that I have received from my wife and my entire family. Thank you for everything, and I dedicate this thesis to all of you, but especially to the person that most embodies all those humanist qualities this thesis attempts to celebrate and honor. That person is my father. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.. ... .. v INTRODUCTION................. CHAPTER I. HUMANISM: THE ESSENCE OF THE RENAISSANCE. -

Experiencing the Chapterhouse in the Benedictine Abbey at Pomposa

Experiencing the Chapterhouse in the Benedictine Abbey at Pomposa The Benedictine Abbey at Pomposa is located in the Po valley east of Ferrara, on the isolated and marshy coastline of the Adriatic Sea.1 Established in the eighth century, it was an active and vibrant complex for almost a thousand years, until repeated outbreaks of malaria forced the monks to abandon it in the seventeenth century (Salmi 14). Notable monks associated with the abbey in its eleventh-century heyday include the music theorist Guido d’Arezzo (c. 991-after 1033), the pious abbot St. Guido degli Strambiati (c. 970-1046), and the writer and reformer St. Peter Damian (1007-72) (Caselli 10-15). The poet Dante called on the abbey, as an emissary for the da Polenta court in Ravenna, shortly before his death in 1321 (Caselli 16). His visit coincided with a great period of renewal under the administration of the abbot Enrico (1302-20), during which fresco cycles in the Chapterhouse and Refectory were executed by artists of the Riminese school. This investigation of the Chapterhouse (Fig. 1-3) reveals that the Benedictines at the Pomposa Abbey, just prior to 1320, created an environment in which illusionistic painting techniques are coupled with references to rhetorical dialogue and theatrical conventions, to allow for the performative and interactive engagement of those who use the space and those depicted on the surrounding walls.2 FLEMING Fig. 1 Pomposa Chapterhous, interior view facing crucifixion (photo: author) Fig. 2 Pomposa Chapterhouse, interior view towards left wall (photo: author) 140 EXPERIENCING THE CHAPTERHOUSE AT POMPOSA Fig. -

Artistic Identity in the Polipl2ilo

Artistic Identity in the Polipl2ilo Helena K. Sz6pet The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili,or Strife of Love in a Dream of Poliphilo as the title has been translated into English, is one of the most famous yet puzzling products of the Aldine press. Despite an enormous scholarly literature, the identities of the author and artists of this intentionally hermetic book remain greatly debated.I Indeed, because the Poliphilo is the only extensively illustrated book printed by the press, and because of the unscholarly, some- what scandalous nature of the text, it has been argued that Aldus could hardly have had much to do with its initial publication in 1499.2 The Poliphilo, nevertheless, remains one of the central monuments of the Renaissance, and many of its 172 anonymous woodcut illustrations have been cited as sources for important motifs in painting and sculpture from the Renaissance through Baroque eras in Venice and throughout Europe (figs. I and 2).3 Over the past Ioo years, historians have attributed the Poliphilo woodcuts to many different artists, including the painters Bon- consigli, Giovanni and Gentile Bellini, Botticelli, Bartolomeo and Benedetto Montagna, Palma Vecchio, Cima da Conegliano, Franco Francia, Titian, Benozzo Gozzoli and Pinturricchio, and Agabiti; the medalists Peregrini and Sperandio; the printmakers Giulio Campagnola, Jacopo de' Barbari, an anonymous 'Dolphin Master;' and the miniaturists the 'Second Grifo Mlaster' and Benedetto Bordon.4 Attempts to attribute the woodcuts to an artist clearly bring into question the efficacy of stylistic analysis for artistic attribution in this book. The perpetually debated attribution of the Poliphilo woodcuts is partially re-examined here by first asking, why is it important to know the artist/s of the Poliphilo? What is at stake, and how does that in part determine the attribution? The question of style is then rephrased from a codicological perspective.s The attempt to t Helena K. -

The “Egg” of the Pala Montefeltro by Piero Della Francesca and Its Symbolic Meaning

The “Egg” of the Pala Montefeltro by Piero della Francesca and its symbolic meaning Sebastian Bock Freiburg i.Br./Heidelberg, 2002 Probably the best-known “egg” in the whole of European art history is the ovoid object depicted in Piero della Francesca’s Montefeltro Altarpiece in the Pinacoteca Brera, Milano (fig. 1). This object, which is shown suspended from the apse by a chain, has formed the subject of so many analyses of Piero’s painting that Shearman’s 1968 observation, that virtually a whole special branch of art history has grown up around the exclusive study of this “egg”,1 appears truly justified. The often passionately argued debate has continued for decades, without reaching a conclusion. At the center of the argument is the identification of the egg-shaped object, which is variously taken to represent a pearl,2 an ostrich egg,3 a hen’s egg,4 the egg of Leda5 as described by Pausanias, or an (unspecific) My sincerest thanks go to Dr. Maria Effinger, Heidelberg, and Dr. Christian Gildhoff, Freiburg i.Br., for a close reading and helpful criticism, as well as Dr. Alexandra Villing, London, for the translation into English. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations from the Greek and Latin are by the author and the translator. Frequently cited sources: — Gilbert, Creighton, “On Subject and Not-Subject in Italian Renaissance Pictures,” Art Bulletin 34 (1952): 202–16. — Meiss, Millard, The Painter’s Choice: Problems in the Interpretation of Renaissance Art [New York. Hagerstown, San Francisco, London: Harper & Row, 1976], 105-129. — Ragusa, Isa, “The Egg Reopened,” Art Bulletin 53 (1971): 435-43. -

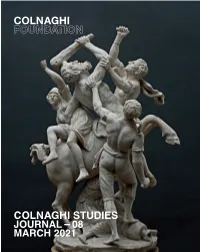

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

San Michele in Foro Representative of Late Romanesque Architecture in Lucca

SAN MICHELE IN FORO REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTURE IN LUCCA by Muriel Beatrice Wolverton A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in the Department of Fine Arts We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1972. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head, of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Depa rtment The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada i ABSTRACT The phenomenal expansion of church building during the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries can be noted in Lucca as elsewhere. The power of the Benedictine Order and the Bishopric, the increase in wealth because of the silk industry as well as a prime position on the trade route between Italy and North Europe, and rivalries with Florence and Pisa,all promoted a flourishing of the arts in Lucca during the Romanesque period. An attempt has been made in this paper to draw attention to the architectural background in Lucca during the Romanesque period. The architecture appears to be divided into two phases. The first phase demonstrates a classic simplicity that appears to relate to the Early Christian basilical church with the possible intrusion of Lombard ideas. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO's LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin

ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin Under the Direction of Shelley Zuraw ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes Andrea del Castagno’s fresco of the Last Supper in the refectory of Sant’Apollonia, Florence. This study investigates the details of the commission, Castagno’s fresco in the iconographic tradition of representations of the Last Supper, the aspects which separate this Last Supper from previous examples in Florentine refectories, the fresco’s purpose in relation to its conventual setting, and also the artist’s use of both classicizing and contemporary elements and techniques. The central focus of my work is the significance of this fresco in terms of both the imagery Castagno employs and his possible sources. The purpose of this thesis is to recognize the innovative aspects of the fresco, as well as the role that Castagno played in the development of Florentine Renaissance art. INDEX WORDS: Andrea del Castagno, Castagno, Last Supper, Sant’Apollonia, Florentine refectories, Italian Renaissance painting, Fresco, Fictive marble ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin B.A., University of Alabama, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ART ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Eva Maria Lundin All Rights Reserved. ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin Major Professor: Shelley Zuraw Committee: Andrew Ladis Asen Kirin Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2006 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the numerous people who have helped me throughout the past two and a half years, most importantly, the faculty, staff, and my fellow graduate students at the University of Georgia.