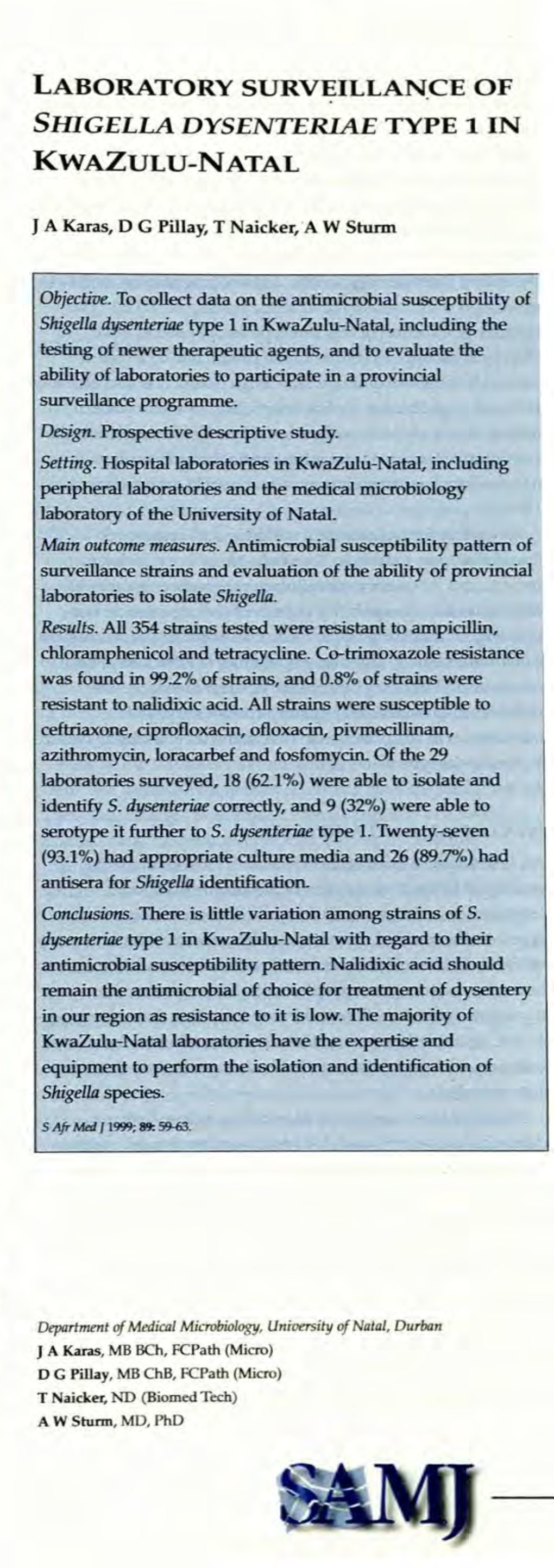

SWGELLA DYSENTERIAE TYPE 1 in Kwazulu-NATAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical Review(S) Clinical Review

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 200327 MEDICAL REVIEW(S) CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type NDA Application Number(s) 200327 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) December 29, 2009 Received Date(s) December 30, 2009 PDUFA Goal Date October 30, 2010 Division / Office Division of Anti-Infective and Ophthalmology Products Office of Antimicrobial Products Reviewer Name(s) Ariel Ramirez Porcalla, MD, MPH Neil Rellosa, MD Review Completion October 29, 2010 Date Established Name Ceftaroline fosamil for injection (Proposed) Trade Name Teflaro Therapeutic Class Cephalosporin; ß-lactams Applicant Cerexa, Inc. Forest Laboratories, Inc. Formulation(s) 400 mg/vial and 600 mg/vial Intravenous Dosing Regimen 600 mg every 12 hours by IV infusion Indication(s) Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infection (ABSSSI); Community-acquired Bacterial Pneumonia (CABP) Intended Population(s) Adults ≥ 18 years of age Template Version: March 6, 2009 Reference ID: 2857265 Clinical Review Ariel Ramirez Porcalla, MD, MPH Neil Rellosa, MD NDA 200327: Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) Table of Contents 1 RECOMMENDATIONS/RISK BENEFIT ASSESSMENT ......................................... 9 1.1 Recommendation on Regulatory Action ........................................................... 10 1.2 Risk Benefit Assessment.................................................................................. 10 1.3 Recommendations for Postmarketing Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies ........................................................................................................................ -

Ladenburg Thalmann Healthcare Conference

Ladenburg Thalmann Healthcare Conference July 13, 2021 Forward-looking Statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements as defined in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 regarding, among other things, the design, initiation, timing and submission to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a New Drug Application (NDA) for tebipenem HBr and the potential approval of tebipenem HBr by the FDA; future commercialization, the potential number of patients who could be treated by tebipenem HBr and market demand for tebipenem HBr generally; expected broad access across payer channels for tebipenem HBr; the expected pricing of tebipenem HBr and the anticipated shift in treating patients from intravenous to oral administration; the initiation, timing, progress and results of the Company’s preclinical studies and clinical trials and its research and development programs, including management’s assessment of such results; the direct and indirect impact of the pandemic caused by an outbreak of a new strain of coronavirus on the Company’s business and operations; the timing of the availability of data from the Company’s clinical trials; the timing of the Company’s filings with regulatory agencies; product candidate benefits; competitive position; business strategies; objectives of management; potential growth opportunities; potential market size; reimbursement matters; possible or assumed future results of operations; projected costs; and the Company’s cash forecast and the availability of additional non-dilutive funding from governmental agencies beyond any initially funded awards. In some cases, forward-looking statements can be identified by terms such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “plan,” “aim,” “anticipate,” “could,” “intent,” “target,” “project,” “contemplate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “predict,” “potential” or “continue” or the negative of these terms or other similar expressions. -

Below Are the CLSI Breakpoints for Selected Bacteria. Please Use Your Clinical Judgement When Assessing Breakpoints

Below are the CLSI breakpoints for selected bacteria. Please use your clinical judgement when assessing breakpoints. The lowest number does NOT equal most potent antimicrobial. Contact Antimicrobial Stewardship for drug selection and dosing questions. Table 1: 2014 MIC Interpretive Standards for Enterobacteriaceae (includes E.coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Serratia and Proteus spp) Antimicrobial Agent MIC Interpretive Criteria (g/mL) Enterobacteriaceae S I R Ampicillin ≤ 8 16 ≥ 32 Ampicillin-sulbactam ≤ 8/4 16/8 ≥ 32/16 Aztreonam ≤ 4 8 ≥ 16 Cefazolin (blood) ≤ 2 4 ≥ 8 Cefazolin** (uncomplicated UTI only) ≤ 16 ≥ 32 Cefepime* ≤ 2 4-8* ≥ 16 Cefotetan ≤ 16 32 ≥ 64 Ceftaroline ≤ 0.5 1 ≥ 2 Ceftazidime ≤ 4 8 ≥ 16 Ceftriaxone ≤ 1 2 ≥ 4 Cefpodoxime ≤ 2 4 ≥ 8 Ciprofloxacin ≤ 1 2 ≥ 4 Ertapenem ≤ 0.5 1 ≥ 2 Fosfomycin ≤ 64 128 ≥256 Gentamicin ≤ 4 8 ≥ 16 Imipenem ≤ 1 2 ≥ 4 Levofloxacin ≤ 2 4 ≥ 8 Meropenem ≤ 1 2 ≥ 4 Piperacillin-tazobactam ≤ 16/4 32/4 – 64/4 ≥ 128/4 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole ≤ 2/38 --- ≥ 4/76 *Susceptibile dose-dependent – see chart below **Cefazolin can predict results for cefaclor, cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefprozil, cefuroxime axetil, cephalexin and loracarbef for uncomplicated UTIs due to E.coli, K.pneumoniae, and P.mirabilis. Cefpodoxime, cefinidir, and cefuroxime axetil may be tested individually because some isolated may be susceptible to these agents while testing resistant to cefazolin. Cefepime dosing for Enterobacteriaceae ( E.coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Citrobacter, Serratia & Proteus spp) Susceptible Susceptible –dose-dependent (SDD) Resistant MIC </= 2 4 8 >/= 16 Based on dose of: 1g q12h 1g every 8h or 2g every 8 h Do not give 2g q12 Total dose 2g 3-4g 6g NA Table 2: 2014 MIC Interpretive Standards for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp. -

Principles of Antimicrobial Drugs

Cephalosporins LECTURE 22 DR.SUHEIL DONE BY: 7ALA RAED Cephalosporins Derivatives of 7-aminocephalosporanic acid β- lactam antibiotics, Cidal effect ,Semisynthetic, from funges Broad spectrum Inhibitors of microbial cell wall synthesis (similar way to penicillin) Differ in pharmacokinetic properties and spectrum of activity Classified into 1st 2nd 3rd 4th and 5th generations ركزوا First generation * على الملون بالزهري Cefadroxil Cefalexin Oral Cefazolin IM, IV Cephapirin Cephradine Cephaloridine * Second generation Cefaclor Oral Cephamandole IM, IV ركزوا على الزهري )اﻷصفر الي حكى عنهم الدكتور ( Cephmetazole Cefonicid Cefotetan Cefoxitin Cefprozil Cefuroxime Cefuroxime axetil Loracarbef * Third generation Cefixime Oral Cefoperazone IM, IV Cefdinir Cefpodoxime Cefotaxims Ceftazidime Ceftriaxone Ceftibuten Ceftizoxime * Fourth generation Cefepime IM, IV * Fifth generation Ceftaroline IV 1st generation cephalosporins have the best activity against G+ve microorganisms, less resistant to β- lactamases, and do not cross readily the BBB as compared to 2nd, 3rd and 4h generations Cephalosporins never considered drugs of choice for any infection, however they are highly effective in upper and lower respiratory infection, H. influenza, UTI’s, dental infections, severe systemic infection... كله حفظ يعني ** Among cephalosporins: - Cefoxitin (2nd) has the best activity against Bacteroides fragilis - Cefamandole (2nd) has the best activity against H. influenza - Cefoperazone (3rd), Ceftazidine (3rd) and Cefepime (4th) have the best activity against P. -

Non-Penicillin Beta-Lactam Drugs: a CGMP Framework for Preventing Cross- Contamination

Guidance for Industry Non-Penicillin Beta-Lactam Drugs: A CGMP Framework for Preventing Cross- Contamination U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) April 2013 Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMPs) Guidance for Industry Non-Penicillin Beta-Lactam Drugs: A CGMP Framework for Preventing Cross- Contamination Additional copies are available from: Office of Communications Division of Drug Information, WO51, Room 2201 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002 Phone: 301-796-3400; Fax: 301-847-8714 [email protected] http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) April 2013 Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) Contains Nonbinding Recommendations TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................2 III. RECOMMENDATIONS.........................................................................................................7 i Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Guidance for Industry1 Non-Penicillin Beta-Lactam Drugs: A CGMP Framework for Preventing Cross-Contamination This guidance -

HKUST 2011 Igem Team

HKUST 2011 iGEM Team E. trojan – Boosting the effectiveness of antibiotics through quorum- sensing disruption INTRODUCTION Mistakes… Penicillin G Amikacin, Gentamicin, Kanamycin, Neomycin, Netilmicin, Tobramycin, Paromomycin, Loracarbef, Ertapenem, Doripenem, Imipenem, Meropenem, Cefadroxil, Cefazolin, Cefalotin, Cefalexin, Cefaclor, Cefamandole, Cefoxitin, Cefprozil, Cefuroxime, Cefixime, Cefdinir, Cefditoren, Cefoperazone, Cefotaxime, Cefpodoxime, Ceftazidime, Ceftibuten, Ceftizoxime, Ceftriaxone, Cefepime, Ceftobiprole, Teicoplanin, Vancomycin, Telavancin, Clindamycin, Lincomycin, Daptomycin, Azithromycin, Clarithromycin, Dirithromycin, Erythromycin, Roxithromycin, Troleandomycin, Telithromycin, Spectinomycin, Aztreonam, Furazolidone, Nitrofurantoin, Amoxicillin, Ampicillin, Azlocillin, Carbenicillin, Cloxacillin, Dicloxacillin, Flucloxacillin, Mezlocillin, Methicillin, Nafcillin, Oxacillin, Penicillin, Piperacillin, Temocillin, Ticarcillin, Bacitracin, Colistin, Polymyxin B … Charity Indole Signalling Rearm Antibiotics ReduceAntibiotic Antibiotic-Free Disruption (T4MO) E. TROJAN SelectionUsage E. CRAFT – AN ALTERNATIVE TRANSFORMATION METHOD Essential- gene- based selection method: E. CRAFT Eschericia coli Re-engineered for Antibiotic- Free Transformation Deletion of an essential gene from E. CRAFT’s genome Addiction to extragenomic source of the gene pCarrier, a heat- insensitive analog of pDummy TRANSFORMATION TRANSFORMATION The selection, comparison between successful and unsuccessful transformation PLASMID SHUFFLING Development -

Vs. Long-Course Antibiotic Treatment for Acute Streptococcal Pharyngitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

antibiotics Review Short- vs. Long-Course Antibiotic Treatment for Acute Streptococcal Pharyngitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Anna Engell Holm * , Carl Llor, Lars Bjerrum and Gloria Cordoba Research Unit for General Practice and Section of General Practice, Department of Public Health, Øster Farimagsgade 5, 1014 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (G.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-261-110-54 Received: 9 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: BACKGROUND: To evaluate the effectiveness of short courses of antibiotic therapy for patients with acute streptococcal pharyngitis. METHODS: Randomized controlled trials comparing short-course antibiotic therapy ( 5 days) with long-course antibiotic therapy ( 7 days) for patients with ≤ ≥ streptococcal pharyngitis were included. Two primary outcomes: early clinical cure and early bacterial eradication. RESULTS: Fifty randomized clinical trials were included. Overall, short-course antibiotic treatment was as effective as long-course antibiotic treatment for early clinical cure (odds ratio (OR) 0.85; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79 to 1.15). Subgroup analysis showed that short-course penicillin was less effective for early clinical cure (OR 0.43; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.82) and bacteriological eradication (OR 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.61) in comparison to long-course penicillin. Short-course macrolides were equally effective, compared to long-course penicillin. Finally, short-course cephalosporin was more effective for early clinical cure (OR 1.48; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.96) and early microbiological cure (OR 1.60; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.27) in comparison to long-course penicillin. -

A Drug Combination Screen Identifies Drugs Active Against Amoxicillin

fmicb-07-00743 May 20, 2016 Time: 19:28 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 23 May 2016 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00743 A Drug Combination Screen Identifies Drugs Active against Amoxicillin-Induced Round Bodies of In Vitro Borrelia burgdorferi Persisters from an FDA Drug Library Jie Feng1, Wanliang Shi1, Shuo Zhang1, David Sullivan1, Paul G. Auwaerter2 and Ying Zhang1* 1 Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2 Fisher Center for Environmental Infectious Diseases, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA Although currently recommended antibiotics for Lyme disease such as doxycycline or amoxicillin cure the majority of the patients, about 10–20% of patients treated Edited by: Octavio Luiz Franco, for Lyme disease may experience lingering symptoms including fatigue, pain, or Universidade Católica de Brasília, joint and muscle aches. Under experimental stress conditions such as starvation Brazil or antibiotic exposure, Borrelia burgdorferi can develop round body forms, which Reviewed by: are a type of persister bacteria that appear resistant in vitro to customary first-line Tom Coenye, Ghent University, antibiotics for Lyme disease. To identify more effective drugs with activity against the Belgium round body form of B. burgdorferi, we established a round body persister model Elizabete De Souza Cândido, Catholic University Dom Bosco, induced by exposure to amoxicillin (50 mg/ml) and then screened the Food and Brazil Drug Administration drug library consisting of 1581 drug compounds and also 22 *Correspondence: drug combinations using the SYBR Green I/propidium iodide viability assay. We Ying Zhang identified 23 drug candidates that have higher activity against the round bodies of [email protected] B. -

Guidelines on Urological Infections

Guidelines on Urological Infections M. Grabe (Chairman), T.E. Bjerklund-Johansen, H. Botto, M. Çek, K.G. Naber, P. Tenke, F. Wagenlehner © European Association of Urology 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Pathogenesis of urinary tract infections 7 1.2 Microbiological and other laboratory findings 7 1.3 Classification of urological infections 8 1.4 Aim of guidelines 8 1.5 Methods 9 1.6 Level of evidence and grade of guideline recommendations 9 1.7 References 9 2. UNCOMPLICATED URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS IN ADULTS 11 2.1 Definition 11 2.1.1 Aetiological spectrum 11 2.2 Acute uncomplicated cystitis in premenopausal, non-pregnant women 11 2.2.1 Diagnosis 11 2.2.1.1 Clinical diagnosis 11 2.2.1.2 Laboratory diagnosis 11 2.2.2 Therapy 11 2.2.3 Follow up 12 2.3 Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis in premenopausal, non-pregnant women 12 2.3.1 Diagnosis 12 2.3.1.1 Clinical diagnosis 12 2.3.1.2 Laboratory diagnosis 12 2.3.1.3 Imaging diagnosis 13 2.3.2 Therapy 13 2.3.2.1 Mild and moderate cases of acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis 13 2.3.2.2 Severe cases of acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis 13 2.3.3 Follow-up 14 2.4 Recurrent (uncomplicated) UTIs in women 16 2.4.1 Diagnosis 16 2.4.2 Prevention 16 2.4.2.1 Antimicrobial prophylaxis 16 2.4.2.2 Immunoactive prophylaxis 16 2.4.2.3 Prophylaxis with probiotics 17 2.4.2.4 Prophylaxis with cranberry 17 2.5 Urinary tract infections in pregnancy 17 2.5.1 Definition of significant bacteriuria 17 2.5.2 Screening 17 2.5.3 Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria 17 2.5.4 Duration of therapy 18 2.5.5 Follow-up 18 2.5.6 Prophylaxis 18 2.5.7 Treatment of pyelonephritis 18 2.5.8 Complicated UTI 18 2.6 UTIs in postmenopausal women 18 2.6.1 Risk factors 18 2.6.2 Diagnosis 18 2.6.3 Treatment 18 2.7 Acute uncomplicated UTIs in young men 19 2.7.1 Men with acute uncomplicated UTI 19 2.7.2 Men with UTI and concomitant prostate infection 19 2.8 Asymptomatic bacteriuria 19 2.8.1 Diagnosis 19 2.8.2 Screening 19 2.9 References 26 3. -

Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine – 5Th Revision. Geneva

WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (AGISAR) Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine 5th Revision 2016 Ranking of medically important antimicrobials for risk management of antimicrobial resistance due to non-human use Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine – 5th rev. ISBN 978-92-4-151222-0 © World Health Organization 2017, Updated in June 2017 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine – 5th rev. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. -

Amoxicillin Statistical Pediatric Review

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Pharmacoepidemiology and Statistical Science Office of Biostatistics S TATISTICAL R EVIEW AND E VAL UATION CLINICAL STUDIES NDA/Serial Number: 50-813 Drug Name: APC-111 MP Tablet, 775 mg (Amoxicillin Pulsatile Formulation) Indication(s): Treatment of Tonsillitis and/or Pharyngitis Secondary to Streptococcus Pyogenes (S. pyogenes) in Adolescents and Adults Applicant: Middlebrook Pharmaceutical Date(s): Stamp Date: March 23, 2007 PDUFA due date: January 22, 2008 Review Priority: Standard Biometrics Division: Division of Biometrics IV Statistical Reviewer: Yan Wang, Ph.D Statistical Team Leader: Thamban Valappil, Ph.D Medical Division: Division of Anti-infective and Ophthalmologic Drug Products (HFD- 520) Clinical Team: Imoisili Menfo, MD Clinical Team Leader: John Alexander, MD, MPH Project Manager: Susmita Samanta 1 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................3 1.1 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS.........................................................................................................3 1.2 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CLINICAL STUDIES..........................................................................................................3 1.3 STATISTICAL ISSUES AND FINDINGS.................................................................................................................4 2. -

Common Antibiotics

Common Antibiotics GROUP I: Ample Spectrum Penicillins Generic Name Trade Name Amoxicillin Amoxil® Ampicillin Omnipen® Bacampicillin Spectrobid® Carbenicillin Indanyl Pyopen®, Geogen®, Geocillin® Mezlocillin Mezlin® Piperacillin* Pipracil® Ticarcillin Ticar® GROUP II: Penicillins and Beta Lactamase Inhibitors Generic Name Trade Name Amoxicillin-Clavulanic Acid Augmentin® Ampicillin-Sulbactam* Unasyn® Benzylpenicillin Benpen® Cloxacillin Tegopen®, Coxapen® Dicloxacillin Dycill®, Dynapen®, Pathocil® Methicillin Staphcillin® Oxacillin Prostaphilin®, Bactocil® Penicillin G (Benzathine, Potassium, Bicillin® C-R/L-A, Pfizerpen®, Wycellin® Procaine) Penicillin V Pen-Veek®, Beepen-VK® Piperacillin+Tazobactam* Zozyn® Ticarcillin+Clavulanic Acid Timentin® Nafcillin Unipen®, Nafcil® GROUP III: Cephalosporins Cephalosporin I Generation Generic Name Trade Name Cefadroxil Duricef® Cefazolin Ancef®, Kefzol®, Zolicef® Cephalexin Keflex®, Keftal®, Cefanox® Cephalothin Keflin®, Seffin® Cephapirin Cefadyl® Cephradine Velocef® 1 Cephalosporin II Generation Generic Name Trade Name Cefaclor Ceclor®, Ceclor CD® Cefamandol Mandol® Cefonicid Monocid® Cefotetan Cefotan® Cefoxitin Mefoxin® Cefprozil Cefzil® Ceftmetazole Zefazone® Cefuroxime Kefurox®, Zinacef® Cefuroxime axetil Ceftin® Loracarbef Lorabid® Cephalosporin III Generation Generic Name Trade Name Cefdinir Omnicef® Ceftibuten Cedax® Cefoperazone Cefobid® Cefixime* Suprax® Cefotaxime* Claforan® Cefpodoxime proxetil Vantin® Ceftazidime* Ceptaz®, Fortaz®, Tanicef® Ceftizoxime* Cefizox® Ceftriaxone* Rocephin®