Living Standards in Lower Canada, 1831

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

By Anne Millar

Wartime Training at Canadian Universities during the Second World War Anne Millar Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy degree in history Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Anne Millar, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 ii Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the contributions of Canadian universities to the Second World War. It examines the deliberations and negotiations of university, government, and military officials on how best to utilize and direct the resources of Canadian institutions of higher learning towards the prosecution of the war and postwar reconstruction. During the Second World War, university leaders worked with the Dominion Government and high-ranking military officials to establish comprehensive training programs on campuses across the country. These programs were designed to produce service personnel, provide skilled labour for essential war and civilian industries, impart specialized and technical knowledge to enlisted service members, and educate returning veterans. University administrators actively participated in the formation and expansion of these training initiatives and lobbied the government for adequate funding to ensure the success of their efforts. This study shows that university heads, deans, and prominent faculty members eagerly collaborated with both the government and the military to ensure that their institutions’ material and human resources were best directed in support of the war effort and that, in contrast to the First World War, skilled graduates would not be heedlessly wasted. At the center of these negotiations was the National Conference of Canadian Universities, a body consisting of heads of universities and colleges from across the country. -

Marine Archaeological Assessment

MARINE ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND RESEARCH AND GEOTECHNICAL SURVEY FOR THE GIBRALTAR POINT EROSION CONTROL PROJECT LAKE ONTARIO SHORELINE ON THE LAKEWARD SIDE OF THE TORONTO ISLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT CITY OF TORONTO Prepared for Toronto and Region Conservation Authority 5 Shoreham Drive North York, Ontario M3N 1S4 and Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport SCARLETT JANUSAS ARCHAEOLOGY INC. 269 Cameron Lake Road Tobermory, Ontario N0H 2R0 phone 519-596-8243 mobile 519-374-1119 [email protected] www.actionarchaeology.ca License # 2016-13 March 1, 2017 © ii Executive Summary The Gibraltar Point Erosion Control Project (the “Project”) will investigate the possibility of developing erosion control infrastructure along Lake Ontario shoreline in the area of Gibraltar Point, Toronto Islands. While the entire Project includes a land based portion as well, the marine archaeological assessment focused on the approximately 600 metre long shoreline and in-water areas. For the purposes of the marine archaeological assessment, the limits of the Project area will be confined to the in-water and previously lakefilled areas. The marine archaeological assessment is comprised of background research and in-water archaeological assessment extending 250 m into Lake Ontario. TRCA with support from the City of Toronto, completed an Environmental Study Report (ESR), in accordance with Conservation Ontario’s Class Environmental Assessment for Remedial Flood and Erosion Control Projects (Class EA) to develop a long‐term solution to address the shoreline erosion around Gibraltar Point (TRCA, 2008). Work was conducted under a marine archaeological license (2016-13) held by Scarlett Janusas. The field portion of the archaeological assessment was conducted over a period of days in September and October of 2016 under good conditions. -

Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA)

Industry Update from Canada: Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA) Monday, 6 July 2020 In partnership with Welcome Michael Barton Regional Director, Canada Invest Northern Ireland – Americas For up to date information on Invest Northern Ireland in the Americas, follow us on LinkedIn & Twitter. Invest Northern Ireland – Americas @InvestNI_USA 2 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian Agri-tech sector… Industry Updates Sessions with industry experts to provide Northern Ireland manufacturers with updates on the Americas markets to assist with export planning and preparation Today’s Update We are delighted to welcome Beverly Leavitt, President & CEO of the Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA). CEEDA represents Equipment Dealers in the Province of Ontario, and the Atlantic Provinces in the Canadian Maritimes. 3 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian Agri-tech sector… Virtual Meet-the-Buyer programs designed to provide 1:1 support to connect Northern Ireland manufacturers with potential Canadian equipment dealers Ongoing dealer development in Eastern & Western Canada For new-to-market exporters, provide support, industry information and routes to market For existing exporters, market expansion and exploration of new Provinces 4 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian -

From European Contact to Canadian Independence

From European Contact to Canadian Independence Standards SS6H4 The student will describe the impact of European contact on Canada. a. Describe the influence of the French and the English on the language and religion of Canada. b. Explain how Canada became an independent nation. From European Contact to Quebec’s Independence Movement • The First Nations are the native peoples of Canada. • They came from Asia over 12,000 years ago. • They crossed the Bering Land Bridge that joined Russia to Alaska. • There were 12 tribes that made up the First Nations. • The Inuit are one of the First Nation tribes. • They still live in Canada today. • In 1999, Canada’s government gave the Inuit Nunavut Territory in northeast Canada. • The first explorers to settle Canada were Norse invaders from the Scandinavian Peninsula. • In 1000 CE, they built a town on the northeast coast of Canada and established a trading relationship with the Inuit. • The Norse deserted the settlement for unknown reasons. • Europeans did not return to Canada until almost 500 years later… • The Italian explorer, John Cabot, sailed to Canada’s east coast in 1497. • Cabot claimed an area of land for England (his sponsor) and named it “Newfoundland”. •Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence River in 1534. •He claimed the land for France. •French colonists named the area “New France”. • In 1608, Samuel de Champlain built the first permanent French settlement in New France— called Quebec. • The population grew slowly. • Many people moved inland to trap animals. • Hats made of beaver fur were in high demand in Europe. -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

Upper Canada, New York, and the Iroquois Six Nations, 1783-1815 Author(S): Alan Taylor Reviewed Work(S): Source: Journal of the Early Republic, Vol

Society for Historians of the Early American Republic The Divided Ground: Upper Canada, New York, and the Iroquois Six Nations, 1783-1815 Author(s): Alan Taylor Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Spring, 2002), pp. 55-75 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press on behalf of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3124858 . Accessed: 02/11/2011 18:25 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Pennsylvania Press and Society for Historians of the Early American Republic are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Early Republic. http://www.jstor.org THE DIVIDED GROUND: UPPER CANADA, NEW YORK, AND THE IROQUOIS SIX NATIONS, 1783-1815 AlanTaylor In recentyears, historians have paid increasing attention to bordersand borderlandsas fluidsites of bothnational formation and local contestation. At theirperipheries, nations and empires assert their power and define their identitywith no certainty of success.Nation-making and border-making are inseparablyintertwined. Nations and empires, however, often reap defiance frompeoples uneasily bisected by theimposed boundaries. This process of border-making(and border-defiance)has been especiallytangled in the Americaswhere empires and republicsprojected their ambitions onto a geographyoccupied and defined by Indians.Imperial or nationalvisions ran up against the tangled complexities of interdependentpeoples, both native and invader. -

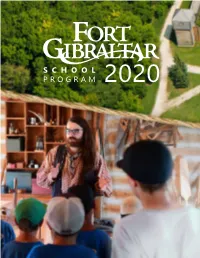

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

Inuit Identities in Montreal, Canada Nobuhiro Kishigami

Document generated on 09/27/2021 6:18 p.m. Études/Inuit/Studies Inuit identities in Montreal, Canada Nobuhiro Kishigami Perspectives inuit et qallunaat : points de vue en interaction Article abstract Inuit and Qallunaaq perspectives: Interacting points of view As Dorais (1994) has indicated, the distinction between the concepts of cultural Volume 26, Number 1, 2002 and ethnic identities are important for us to understand the identities of contemporary Canadian Inuit Although the Inuit themselves do not distinguish URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/009279ar between these identities, I consider them to be useful analytical concepts. I DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/009279ar argue that cultural identity is a tool for an Inuk to live with his fellow Inuit in daily life and that ethnic identity is a political tool especially for both urban and arctic Inuit to deal with others in multi-ethnic situations. See table of contents Publisher(s) Association Inuksiutiit Katimajiit Inc. ISSN 0701-1008 (print) 1708-5268 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this note Kishigami, N. (2002). Inuit identities in Montreal, Canada. Études/Inuit/Studies, 26(1), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.7202/009279ar Tous droits réservés © La revue Études/Inuit/Studies, 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Criminal Law in Upper Canada a Century Ago William Renwick Riddell

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 5 1920 Criminal Law in Upper Canada a Century Ago William Renwick Riddell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation William Renwick Riddell, Criminal Law in Upper Canada a Century Ago, 10 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 516 (May 1919 to February 1920) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CRIMINAL LAW IN UPPER CANADA A CENTURY AGO WILLIAm RENWICK RI7DDELL" When examining for another purpose the original manuscripts in the Archives at Ottawa of the dates shortly before and at the time of the War of 1812-14, I perused many original reports from assize judges2 and other documents of an interesting character from the point of view of criminal law. 'LL.D., F.R.S. Can., etc., Justice of the Supreme Court of Ontario. 2While after the formation of the province there seems to have been no statutory or other obligation of a legal nature upon them so to do, it was the custom from the beginning of the separate provincial life of Upper Canada in 1792, as before, for the trial judges to make a report to the lieutenant governor upon every capital case in which a conviction was made and the prisoner sentenced to death. -

Sir George Williams University Montreal

IN THIS ISSUE • Library Campaign Windup (page 7) • Bridge Tournament Planned (page 8) • Memorial Lectures Success (page 8) • Fall Convocation (page 11) • Separatism: Utility- Futility (page 16) Postgrad ASSOCIATION OF ALUMNI SIR GEORGE WILLIAMS UNIVERSITY MONTREAL WINTER ISSUE DECEMBER 1961 BRINGS OUT ® ,:, ,: . : ' F.. ,: ::: TH!w'~. B',·~.N'EST IN BEER ... FOR EATON'S Is Proud Of The Success Story Of These "Best Seller" Canadian Brands Salonia Every day of the year - from British Columbia to New foundland - Canadians shopping at Eaton's stores are writing a spectacular success story. It's the story of the VIKINC Canadian brands you find only at Eaton's. These familiar labels (only 4 are depicted here) are reassuring signposts to satisfaction every time you shop. Each one of them makes a simple, straightforward promise: full value for llaaaon 1f all your purchasing dollar. All are backed by Eaton's time honoured guarantee: "Goods Satisfactory or Money Refunded." IRlibNE ~T. EATON c~ ... TEI> OF MONTREAL Postgrad The Alumni in Pictures A photo review of the season. Published quarterly by the Association of Alumni of Sir George Williams University, 1435 Drummond Street, Montreal 25, Quebec, Canada. VI. 4-0131, Alumni Office. Authorized as Second Class Mail, Post Office Department, Ottawa. Printed for the Publish ers by Canadian Printing and Lithographing Com pany Limited, 5670 Chauveau Street, Montreal 5. Please address all communications to the Alumni office, 1435 Drummond St., Montreal, Room 338. This trophy case, in the lobby outside Birks Hall, will he presented by the Alumni Association to the U niversity during R eunion W eek in April. -

Early Struggles for Bilingual Schools and the French Language in the Windsor Border Region, 1851–1910

66 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation articles / articles Early Struggles for Bilingual Schools and the French Language in the Windsor Border Region, 1851–1910 Jack D. Cécillon ABSTRACT In 1910, Bishop Michael Fallon of London called for the abolition of the bilingual schools of Ontario because of their inefficiencies. Concerns about the value of a bilingual education and the French language in particular predate Fallon and go back to the 1850s in the Windsor bor- der region. These concerns were voiced by both francophones and anglophones, and illustrate that the struggle for the survival of the French language in the churches and schools of the area predated the arrival of Fallon and the Ontario government’s imposition of Regulation XVII. RÉSUMÉ En 1910, l’évêque de London, Michael Fallon, demanda l’abolition des écoles bilingues on- tariennes en raison de leur inefficacité. Les inquiétudes au sujet de la valeur d’une instruction bilingue et de la langue française, notamment, précédaient Fallon puisqu’elles remontaient aux années 1850 dans la région frontalière de Windsor. Exprimées par les francophones et par les anglophones, elles mettent en lumière le fait que la lutte pour la survivance de la langue française dans les églises et les écoles de la région précédait l’arrivée de Fallon et l’imposition du Règlement XVII par le gouvernement de l’Ontario. Introduction In 1912, the Ontario government, in response to an influx of unilingual French- speaking migrants from Quebec, introduced Regulation XVII, which effectively re- stricted French instruction to one hour a day in the province’s bilingual schools.