Oral History Interview with Bill T. Jones, 2018 March 23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirituals Et Gospel

SPIRITUALS ET GOSPEL un parcours dans les musiques sacrées afro-américaines. Médiathèque François Mitterrand Décembre 2010 1 Histoire des Négro-spirituals Les origines L'origine des Negro Spirituals remonte au temps de l'esclavage. Ces chants, empreints d'espoir et de ferveur religieuse, expriment tout le drame des populations africaines déracinées et vendues pour travailler dans les plantations du sud des Etats-Unis. Le Gospel est une création plus récente née dans les communautés noires américaines des grandes villes du Nord. Tout a commencé en 1619, lorsqu'un navire hollandais débarqua sur les côtes de Virginie les premiers esclaves africains. On trouva que ces hommes s'adaptaient bien au climat et qu'ils pouvaient être d'un excellent profit pour l'économie locale. Aussi d'autres navires négriers suivirent et, année après année, pendant plus de deux siècles, des centaines de milliers d'êtres humains furent arrachés à leur sol natal et transportés, dans des conditions effroyables, vers les rives américaines. Pendant la traversée. Gravure 1840 (Librairie du congrès) 2 L'esclavage fut à son apogée, au début du 19ème siècle, avec le développement du coton. En 1860 on comptait plus de quatre millions d'esclaves aux Etats Unis. La guerre de Sécession et l'influence des mouvements humanistes conduisirent à l'abolition de l'esclavage en 1865. Mais c'est à la même époque qu'apparut le Ku Klux Klan et les réactions ségrégationnistes. La lutte pour une complète et réelle liberté allait encore durer bien des années, jusqu'aux mouvements pour les droits civiques, entre 1960 et 1970, avec l'inoubliable figure de Martin Luther King. -

MEREDITH MONK and ANN HAMILTON: Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc

The House Foundation for the Arts, Inc. | 260 West Broadway, Suite 2, New York, NY 10013 | Tel: 212.904.1330 Fax: 212.904.1305 | Email: [email protected] Web: www.meredithmonk.org Incorporated in 1971, The House Foundation for the Arts provides production and management services for Meredith Monk, Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble, and The House Company. Meredith Monk, Artistic Director • Olivia Georgia, Executive Director • Amanda Cooper, Company Manager • Melissa Sandor, Development Consultant • Jahna Balk, Development Associate • Peter Sciscioli, Assistant Manager • Jeremy Thal, Bookkeeper Press representative: Ellen Jacobs Associates | Tel: 212.245.5100 • Fax: 212.397.1102 Exclusive U.S. Tour Representation: Rena Shagan Associates, Inc. | Tel: 212.873.9700 • Fax: 212.873.1708 • www.shaganarts.com International Booking: Thérèse Barbanel, Artsceniques | [email protected] impermanence(recorded on ECM New Series) and other Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble albums are available at www.meredithmonk.org MEREDITH MONK/The House Foundation for the Arts Board of Trustees: Linda Golding, Chair and President • Meredith Monk, Artistic Director • Arbie R. Thalacker, Treasurer • Linda R. Safran • Haruno Arai, Secretary • Barbara G. Sahlman • Cathy Appel • Carol Schuster • Robert Grimm • Gail Sinai • Sali Ann Kriegsman • Frederieke Sanders Taylor • Micki Wesson, President Emerita MEREDITH MONK/The House Foundation for the Arts is made possible, in part, with public and private funds from: MEREDITH MONK AND ANN HAMILTON: Aaron Copland Fund for -

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“White Christmas”—Bing Crosby (1942) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Cary O’Dell Crosby’s 1945 holiday album Original release label “Holiday Inn” movie poster With the possible exception of “Silent Night,” no other song is more identified with the holiday season than “White Christmas.” And no singer is more identified with it than its originator, Bing Crosby. And, perhaps, rightfully so. Surely no other Christmas tune has ever had the commercial or cultural impact as this song or sold as many copies--50 million by most estimates, making it the best-selling record in history. Irving Berlin wrote “White Christmas” in 1940. Legends differ as to where and how though. Some say he wrote it poolside at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona, a reasonable theory considering the song’s wishing for wintery weather. Some though say that’s just a good story. Furthermore, some histories say Berlin knew from the beginning that the song was going to be a massive hit but another account says when he brought it to producer-director Mark Sandrich, Berlin unassumingly described it as only “an amusing little number.” Likewise, Bing Crosby himself is said to have found the song only merely adequate at first. Regardless, everyone agrees that it was in 1942, when Sandrich was readying a Christmas- themed motion picture “Holiday Inn,” that the song made its debut. The film starred Fred Astaire and Bing Crosby and it needed a holiday song to be sung by Crosby and his leading lady, Marjorie Reynolds (whose vocals were dubbed). Enter “White Christmas.” Though the film would not be seen for many months, millions of Americans got to hear it on Christmas night, 1941, when Crosby sang it alone on his top-rated radio show “The Kraft Music Hall.” On May 29, 1942, he recorded it during the sessions for the “Holiday Inn” album issued that year. -

A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE to BROOKLYN Judith E

L(30 '11 II. BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Edward I. Koch, Hon. Howard Golden, Seth Faison, Paul Lepercq, Honorary Chairmen; Neil D. Chrisman, Chairman; Rita Hillman, I. Stanley Kriegel, Ame Vennema, Franklin R. Weissberg, Vice Chairmen; Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Chief Executive Officer; Harry W. Albright, Jr., Henry Bing, Jr., Warren B. Coburn, Charles M. Diker, Jeffrey K. Endervelt, Mallory Factor, Harold L. Fisher, Leonard Garment, Elisabeth Gotbaum, Judah Gribetz, Sidney Kantor, Eugene H. Luntey, Hamish Maxwell, Evelyn Ortner, John R. Price, Jr., Richard M. Rosan, Mrs. Marion Scotto, William Tobey, Curtis A. Wood, John E. Zuccotti; Hon. Henry Geldzahler, Member ex-officio. A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE TO BROOKLYN Judith E. Daykin Executive Vice President and General Manager Richard Balzano Vice President and Treasurer Karen Brooks Hopkins Vice President for Planning and Development IN HONOR OF THE 100th ANNIVERSARY Micheal House Vice President for Marketing and Promotion ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE STAFF OF THE Ruth Goldblatt Assistant to President Sally Morgan Assistant to General Manager David Perry Mail Clerk BROOKLYN BRIDGE FINANCE Perry Singer Accountant Tuesday, November 30, 1982 Jack C. Nulsen Business Manager Pearl Light Payroll Manager MARKETING AND PROMOTION Marketing Nancy Rossell Assistant to Vice President Susan Levy Director of Audience Development Jerrilyn Brown Executive Assistant Jon Crow Graphics Margo Abbruscato Information Resource Coordinator Press Ellen Lampert General Press Representative Susan Hood Spier Associate Press Representative Diana Robinson Press Assistant PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Jacques Brunswick Director of Membership Denis Azaro Development Officer Philip Bither Development Officer Sharon Lea Lee Office Manager Aaron Frazier Administrative Assistant MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Jack L. -

Imes I Wonder What "Wrang with Me. I Keep Hearing People Soy That They Have Changed Jobs Because Five Or Ten Years in a Job Is Enough

BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Letter from the President ~imes I wonder what "wrang with me. I keep hearing people soy that they have changed jobs because five or ten years in a job is enough. And here I am after 25 years, still at it, and still, for the most part, enjoying the ride. BAM has changed over the years and yet remains steadily on course. The outpouring of new work by some of our "old-timers" and by young, developing artists trying their wings, and the pursuit of several new initiatives, plus the stimulation of my BAM colleagues, have managed to keep me (or part of me) virgin, available and interested. The first major attraction of my initial season at BAM was Sarah Caldwell's newly formed American National Opera Company, which featured the first staged production in New York of Alban Berg's LULU. The next season, in 1968, had the return of The living Theater in four productions new to New York. In 1969, we introduced Jerzy Grotowski's Polish laboratory Theatre in three productions, and also Twyla Tharp's company on the Opera House stage, with the audience also onstage, seated on three sides. Robert Wilson's LIFE AND TIMES OF SIGMUND FREUD also appeared at BAM in 1969. What is the point of view that informed those early years and that is still operative today? It may seem to be contemporary work by artists outside the mainstream. I think it is deeper and more inclusive than that. For me, it is the application of a critical approach informed by a contemporary sensibility, to what is being produced for the stage today. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Dance Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8q2nb58d No online items Guide to the Dance Photograph Collection Processed by Emma Kheradyar. Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Dance Photograph MS-P021 1 Collection Guide to the Dance Photograph Collection Collection number: MS-P021 Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries University of California Irvine, California Contact Information Special Collections and Archives The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California Irvine, California 92623-9557 Phone: (949) 824-3947 Fax: (949) 824-2472 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.uci.edu/rrsc/speccoll.html Processed by: Emma Kheradyar Date Completed: July 1997 Encoded by: James Ryan © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Dance Photograph Collection, Date (inclusive): 1906-1970 Collection number: MS-P021 Extent: Number of containers: 5 document boxes Linear feet: 2 Repository: University of California, Irvine. Library. Dept. of Special Collections Irvine, California 92623-9557 Abstract: The Dance Photograph Collection is comprised of publicity images, taken by commercial photographers and stamped with credit lines. Items date from 1906 to 1970. The images, all silver gelatin, document the repertoires of six major companies; choreographers' original works, primarily in modern and post-modern dance; and individual, internationally known dancers in some of their significant roles. -

Reggie Washington 02

ALBUM DETAILS WORLDWIDE CD RELEASE NOVEMBER 7th, 2018 TRACKLISTING 01. Always Moving (1:13) REGGIE WASHINGTON 02. Fall (7:49) 03. Eleanor Rigby (3:37) 04. Half Position Woody (8:07) 05. Afro Blue (3:10) 06. E.S.P (9:27) « VINTAGE NEW ACOUSTIC » 07. Thoughts of Buckshot (0:58) 08. Footprints (9:29) 09. Moanin‘ (4:28) 10. B3 Blues 4 Leroy (9:44) 11. Always Moving (0:59) (Reprise Ending) PERSONAL REGGIE WASHINGTON acoustic & electric basses BOBBY SPARKS acoustic piano, Fender Rhodes, keyboards & organ FABRICE ALLEMAN saxophones E.J. STRICKLAND drums META DATA ARTIST: Reggie Washington TITLE: Vintage New Acoustic GENRE: Jazz LABEL: Jammin’colorS CATALOG NUMBER: JC18-007-2 UPC: 715235041031 STREET & RADIO ADD DATE: 7 November 2018 ABOUT REGGIE WASHINGTON Reggie Washington is an artist of rare breed who can play acoustic and electric basses, who can sing, who can mix Jazz, Funk & World Music while combining the life of leader and sideman. Reggie was a key participant in the Modern Jazz revolution of the 80’s and 90’s. He became known touring, recording and performing with Steve Coleman, Bran- ford Marsalis, Roy Hargrove, Chico Hamilton, Oliver Lake, Cassandra Wilson, Don Byron, Jean-Paul Bourelly, Lester Bowie, Meshell Ndegeocello to name a few. In 2005, Reggie began successfully touring with his own bands. They were a mix of American & European musicians such as Ravi Coltrane, Gene Lake, Stéphane Galland, Jef Lee Johnson, Erwin Vann, Jacques Schwarz-Bart, E.J. Strickland, Jozef Dumoulin, Matthew Garrison, Marcus Strickland, Jason Lindner, Poogie Bell and Ronny Drayton. TOUR DATES In 2015, Reggie started touring throughout Europe with his project “Rainbow Shadow - A tribute to Jef Lee Johnson“ featuring guitarists Marvin Sewell or Da- VINTAGE NEW ACOUSTIC vid Gilmore, drummer Patrick Dorcéan & DJ Grazzhoppa on turntables. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

From Museums to Film Studios, the Creative Sector Is One of New York City’S Most Important Economic Assets

CREATIVE NEW YORK From museums to film studios, the creative sector is one of New York City’s most important economic assets. But the city’s working artists, nonprofit arts groups and for-profit creative firms face a growing number of challenges. June 2015 www.nycfuture.org CREATIVE NEW YORK Written by Adam Forman and edited by David Giles, Jon- CONTENTS athan Bowles and Gail Robinson. Additional research support from from Xiaomeng Li, Travis Palladino, Nicho- las Schafran, Ryan MacLeod, Chirag Bhatt, Amanda INTRODUCTION 3 Gold and Martin Yim. Cover photo by Ari Moore. Cover design by Amy ParKer. Interior design by Ahmad Dowla. A DECADE OF CHANGE 17 Neighborhood changes, rising rents and technology spark This report was made possible by generous support anxiety and excitement from New York Community Trust, Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, Rock- SOURCES OF STRENGTH 27 efeller Brothers Fund and Edelman. Talent, money and media make New York a global creative capital CENTER FOR AN URBAN FUTURE CREATIVE VOICES FROM AROUND THE WORLD 33 120 Wall St., Fl. 20 New YorK, NY 10005 Immigrants enrich New York’s creative sector www.nycfuture.org THE AFFORDABILITY CRISIS 36 Center for an Urban Future is a results-oriented New Exorbitant rents, a shortage of space and high costs York City-based think tank that shines a light on the most critical challenges and opportunities facing New ADDITIONAL CHALLENGES 36 YorK, with a focus on expanding economic opportunity, New York City’s chief barriers to variety and diversity creating jobs and improving the lives of New York’s most vulnerable residents. -

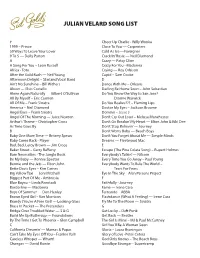

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Press Release: for Immediate Release

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Mike Michelon, Executive Director 734-994-5899, [email protected] #### Ann Arbor Summer Festival Announces First Shows of the Season ANN ARBOR MI (February 12, 2020) – The Ann Arbor Summer Festival is pleased to announce three headlining ticketed performances for the festival’s 2020 season. Festival Executive Director Mike Michelon shares, “We are thrilled to announce three of our ticketed shows early this season. Our 37th season will feature an eclectic mix of a Broadway icon, a world class illusionist, and an infamous comedy troupe returning for their 21st season.” The remaining ticketed performances will be announced in March. The full Top of the Park season will be announced on May 1. Festival Ticket Information Tickets On Sale: Thursday, February 13 at 9 am (General Public) Online: tickets.a2sf.org By Phone: (734) 764-2538 or toll-free in Michigan at (800) 221-1229 In Person: Michigan League Ticket Office, 911 N. University Ave, Ann Arbor MI 48109 Festival Venue Information Power Center for the Performing Arts: 121 Fletcher Street, Ann Arbor, MI Hill Auditorium: 825 N University Ave, Ann Arbor, MI Zingerman’s Greyline: 100 N Ashley St, Ann Arbor, MI Top of the Park: 915 E Washington St, Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor Summer Festival 2020 Ticketed Performances Scott Silven: Wonders at Dusk Wednesday-Friday, June 24-26 at 6:30/7pm Zingerman’s Greyline $55 (plus fees), $35 (plus fees), ages 12-18 Scott Silven is an incomparable modern marvel, and he returns to A2SF after a sold-out run in 2018.