Man and Dog May Have Been “Partners”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spinone Italiano

Spinone Italiano Herkunft: Es wird ursprünglich vermutet dass der Spinone aus dem Piemont stammt, und eines der ältesten Vorstehhunde ist. Es gibt zwei verschiede Meinungen. Die eine, dass er eine Kreuzung aus russischem Griffon und dem Bracco Italiano sei, die andere, dass er aus einem ausgestorbenen spanischen Vorstehhund abstammt, Nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg ist der Spinone fast ausgestorben, da die Italienischen Jäger auf andere Rassen wie der Setter, Pointer oder deutscher Drahthaar griffen. m Gegenzug kam auch der Spinone ins Ausland und hat sich Heute beinahe wieder erholt. Erscheinungsbild: Hund von kräftigem, derbem und widerstandsfähigem Körperbau, kräftiger Knochenbau, gut entwickelte Muskulatur, Rauhaar. Weiß, weiß mit orangefarbenen Platten, weiß - orange geschimmelt, weiß - orange geschimmelt mit orangefarbenen Platten, Braunschimmel, Braunschimmel mit braunen Platten und weiß mit braunen Platten. - Rüden: 60 bis 70cm bei 32 bis 37kg - Hündinnen: 58 bis 65cm bei 28 bis 30kg Rassetypische Erkrankungen Es gibt auch in dieser Rasse eine Cerebralelähmung, die meist so im Alter von einem Jahr auftreten kann. Deutschland hat gleich nach bekannt werden, einen Sammeltest durchgeführt. Arbeitseinsatz Er gilt als hervorragender Vorsteh - und Apportierhund. Der Spinone besitzt ein umgängliches Wesen, er ist leichtführig und geduldig und eignet sich für die Jagd in jedem Gelände. Er ist nahezu unermüdlich und geht willig ins dornige Gestrüpp oder wirft sich ins kalte Wasser. Die Arbeit im Sumpf und Wasser liegt ihm ganz besonders und kann der Gesundheit des exzellenten Schwimmers nichts anhaben, da ihm das robuste Fell vor Feuchtigkeit und kalten Temperaturen schützt. Spinone erweisen sich von Natur aus als vorzügliche Apportierhunde. Er besitzt eine bemerkenswerte Veranlagung zum verlängerten und schnellen Trab. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

Lagotto Romagnolo (Plural Lagotti) Is a Breed of Dog That Comes from the Romagna Sub-Region of Italy

OSDIA EDITION 6 VOLUME 2 LIBERTY, EQUALITY, EDITOR; ANGELA DONATO FRATERNITY [email protected] LODGE 2442 NEWSLETTER Dear Lodge Brothers and Sisters, In January, many of us attended 2 musical experiences at the Connetquot library. Anna Maria Villa and Sal Manzo, both terrific entertainers and I have recommended each of them to the Culture & Heritage Festival Committee for their Event this summer After each event we went out to dinner and had a wonderful time with our Lodge Brothers & Sisters. Remember one of the best things about being part of the Lodge, is that many of our members enjoy activities outside of Lodge functions and events. I want to thank my wife for making the arrangements for us. It’s been a fast two years. I leave the Presidency with a sense of accomplishment. I am confident that Luisa and Dottie will do a fantastic job leading the lodge with integrity and energy. It’s important that you attend the March 4th Installation Ceremony to support the newly elected officers and thank the outgoing officers for a job well done. The ceremony takes place in the front room of the Acampora Center and the dessert that follows is in the regular meeting room. I am looking forward to being the Immediate Past President and active member of the Lodge. Sincerely, President Bob Donato, AVANTI SGT JOHN BASILONE, NICKNAMED “MANILA JOHN” DIED FEBRUARY 19TH 1945 AT IWO JIMA, JAPAN. DOTTIE CURTO ACCEPTING THE NOMINTATION FOR LODGE VICE PRESIDENT. PETE & ROB ENJOYING COFFEE STATE TRUSTEE GERALDINE GRAHAM & PRESIDENT BOB CARLO DID A GREAT JOB AS USUAL READING THE LIST OF NEW BOARD MEMBERS FOR US TO VOTE ON. -

2020 AKC Fast CAT Invitational Results AKC Speed of the Breed TM

2020 AKC Fast CAT Invitational Results AKC Speed of the Breed TM Run 1 Run 2 Run 3 RANK Dog's Call Name Breed Speed of the Breed (Wednesday) (Thursday) (Friday) Average % Over/Under 1 Elliot Poodle (Small) 17.43 22.988 23.762 24.353 23.701 35.98% 2 Sheldon Pomeranian 15.06 20.288 20.393 20.069 20.250 34.46% 3 Jack Dachshund (Small) 12.94 16.778 16.838 17.536 17.051 31.77% 4 Phelan All American Dogs (Large) 25.35 32.202 32.258 32.232 32.230 27.14% 5 Gif All American Dogs (Medium) 23.22 29.580 29.473 29.330 29.461 26.88% 6 Joker Miniature Schnauzer 19.59 25.178 25.178 24.115 24.824 26.72% 7 Norby Toy Fox Terrier 18.92 23.430 23.765 23.533 23.576 24.61% 8 Starla French Bulldog 17.89 21.725 22.132 21.705 21.854 22.16% 9 Kelli Great Dane 23.27 27.135 28.854 29.137 28.376 21.94% 10 Vito Shetland Sheepdog 20.67 24.805 24.914 25.299 25.006 20.98% 11 Capone Miniature Pinscher 19.48 23.355 23.358 23.707 23.473 20.50% 12 Angelique Basset Hound 14.42 17.935 17.982 15.751 17.223 19.44% 13 Dude Bulldog 17.53 20.728 21.035 20.770 20.844 18.91% 14 Zen Bouvier Des Flandres 22.59 25.817 27.382 26.907 26.702 18.20% 15 Ava Havanese 16.48 18.969 19.503 19.617 19.363 17.49% 16 Turbo Boston Terrier 21.53 24.787 25.187 25.094 25.023 16.22% 17 Albus Manchester Terrier (Medium) 22.01 25.252 25.706 25.623 25.527 15.98% 18 Bongo Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier 22.43 25.703 25.911 25.778 25.797 15.01% 19 Bulleit English Springer Spaniel 23.18 27.265 26.167 26.200 26.544 14.51% 20 Oscar Portuguese Water Dog 22.40 25.064 25.911 25.745 25.573 14.17% 21 Jamie Irish Water -

Quiz Sheets BDB JWB 0513.Indd

2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write one breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet and receive one point for each correct answer. There’s an extra five points on offer for those that can find correct answers for Q, U, X and Z! A N B O C P D Q E R F S G T H U I V J W K X L Y M Z Dogs for the Disabled The Frances Hay Centre, Blacklocks Hill, Banbury, Oxon, OX17 2BS Tel: 01295 252600 www.dogsforthedisabled.org supporting Registered Charity No. 1092960 (England & Wales) Registered in Scotland: SCO 39828 ANSWERS 2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write a breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet (one point each). Additional five points each if you get the correct answers for letters Q, U, X or Z. Or two points each for the best imaginative breed you come up with. A. Curly-coated Retriever I. P. Tibetan Spaniel Affenpinscher Cuvac Ibizan Hound Papillon Tibetan TerrieR Afghan Hound Irish Terrier Parson Russell Terrier Airedale Terrier D Irish Setter Pekingese U. Akita Inu Dachshund Irish Water Spaniel Pembroke Corgi No Breed Found Alaskan Husky Dalmatian Irish Wolfhound Peruvian Hairless Dog Alaskan Malamute Dandie Dinmont Terrier Italian Greyhound Pharaoh Hound V. Alsatian Danish Chicken Dog Italian Spinone Pointer Valley Bulldog American Bulldog Danish Mastiff Pomeranian Vanguard Bulldog American Cocker Deutsche Dogge J. Portugese Water Dog Victorian Bulldog Spaniel Dingo Jack Russel Terrier Poodle Villano de Las American Eskimo Dog Doberman Japanese Akita Pug Encartaciones American Pit Bull Terrier Dogo Argentino Japanese Chin Puli Vizsla Anatolian Shepherd Dogue de Bordeaux Jindo Pumi Volpino Italiano Dog Vucciriscu Appenzeller Moutain E. -

The Spinone Italiano

The Breed of the Month is… The Spinone Italiano Origin Although not common in the U.S., this breed has a long history of service to man. The breed is known as Italy's all-purpose hunting dog. Some say it is a cross between White Mastiff, French Griffon and the coarse-haired Italian Setter, bred with the dogs that were left by Greek traders and others from the Adriatic coast. However this is not proven and the dog's rather uncertain heritage centers around Europe and its gun dogs of long ago. Whether this was the basis for bringing forth other gun breeds, or whether they simply sprang from common stock is not known. Like all Italian breeds it is ancient. In Renaissance Italy a pointer with wirey hair was already present. After 1950 the breed was reconstructed by a few great breeders. The dogs have a great sense of smell, setting, retrieving, recovering, and very close ties with the hunter. The breed has excelled as a pointer and retriever for centuries. Today he is still a popular hunting dog in other countries, as well as a pet. The AKC recognized the Spinone Italiano in 2000. Discription The Spinone Italiano, also known as the Spinone, Italian Spinone or Italian Griffon, is a large, rugged looking dog with a long head. The muzzle is square when viewed from the side and is the same length as the backside of the skull. The stop is very slight. The nose has large, wide open nostrils and is flesh colored in white dogs, darker in white and orange dogs and brown in brown or brown roan dogs. -

Group Results Sporting Hound Working Terrier Toy Non-Sporting Herding

North Arkansas Kennel Club Thursday, November 5, 2020 Group Results Sporting Spaniels (English Springer) 21 BB/G1 GCHG CH Cerise Bonanza. SR89255201 Spaniels (Cocker) Black 9 BB/G2 GCHS CH Aladdin's Twist Of Fate Tastic. SR93825901 Pointers 16 BB/G3 GCHB CH Solivia's Decisions Decisions. SS06865003 Pointers (German Shorthaired) 21 BB/G4 GCHB CH Ehrenvogel Guns Blazing. SR92851106 Hound Salukis 5 BB/G1 GCHG CH Aurora's Rhythm Of My Heart. HP49192101 Irish Wolfhounds 17 BB/G2 CH New Yorker Prince Ionmhain Norman. HP54295701 Treeing Walker Coonhounds 5 1/W/BB/G3 Lost Heritage Knight Of Eldorado. HP60141401 Beagles (15 Inch) 15 BB/G4 GCHS CH Deluxe Return On Investment. HP49688101 Working Boxers 16 BB/G1/RBIS GCHP2 CH Cinnibon's Bedrock Bombshell. WS51709601 Rottweilers 7 BB/G2 GCHS CH Bang's Catch Me If You Can RA FDC CA CGCA CGCU TKI. WS50524001 Portuguese Water Dogs 11 BB/G3 CH Success' Wild Card Of Good Fortune. WS65704501 Standard Schnauzers 24 BB/G4 GCH CH Sketchbook Special Edition. WS63106201 Terrier Border Terriers 14 BB/G1 GCHB CH Meadowlake High Times. RN31451901 Scottish Terriers 20 BB/G2 GCHS CH Bravo It's An Industry Term. RN29215601 Soft‐Coated Wheaten Terriers 5 BB/G3 GCHS CH Doubloon's Extreme Gamer. RN30567002 Kerry Blue Terriers 6 1/W/BB/G4 Melbee's That's It. RN32217701 Toy Pomeranians 37 BB/G1 CH Artistry's James Bond. TS44038001 Pugs 7 BB/G2 GCHG CH Casa Blanca's The Fighting Irish. TS37755401 Affenpinschers 5 BB/G3 GCHS CH Point Dexter V. Tani Kazari. -

SPINONE ITALIANO (Italian Spinone)

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ (VALID FROM 01/01/2016) _______________________________________________________________ 17.12.2015/EN FCI-Standard N° 165 SPINONE ITALIANO (Italian Spinone) 2 TRANSLATION: Mrs. Peggy Davis. Revised by Renée Sporre- Willes. Official language (EN). ORIGIN: Italy. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL VALIDSTANDARD: 13.11.2015. UTILIZATION: Pointing dog. FCI-CLASSIFICATION: Group 7 Pointing Dogs. Section 1.3 Continental Pointing Dogs, «Griffon type». With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: Bibliographical descriptions mention a rough-haired dog of Italian origin that passes as being the ancestor of the present Spinone. Sélincourt, in his book Le parfait chasseur (The perfect Hunter) from1683, speaks of a «griffon» coming from Italy and the Piedmont. In the Middle Ages this dog has often been represented by famous painters; the best known painting is a fresco by Andrea Mantegna in the ducal palace of Mantua, from the 15th century. GENERAL APPEARANCE: Dog of solid construction, robust and vigorous with powerful bone, well-developed muscles and with a rough coat. IMPORTANT PROPORTIONS: The build tends to fit into a square. The length of the body is equal to the height at the withers, with a tolerance of 1 to 2 cm longer. The length of the head is equal to 4/10ths of the height at the withers, its width, measured at the level of the zygomatic arches, is inferior to half its length. The loin measures in length a little less than a fifth of the height at the withers. FCI-St. N° 165 / 17.12.2015 3 BEHAVIOUR/TEMPERAMENT: Naturally sociable, docile and patient, the Spinone is an experienced hunter in all terrains; very resistant to tiredness, goes easily into thorny underwood, or throws himself into cold water. -

Best in Grooming Best in Show

Best in Grooming Best in Show crownroyaleltd.net About Us Crown Royale was founded in 1983 when AKC Breeder & Handler Allen Levine asked his friend Nick Scodari, a formulating chemist, to create a line of products that would be breed specific and help the coat to best represent the breed standard. It all began with the Biovite shampoos and Magic Touch grooming sprays which quickly became a hit with show dog professionals. The full line of Crown Royale grooming products followed in Best in Grooming formulas to meet the needs of different coat types. Best in Show Current owner, Cindy Silva, started work in the office in 1996 and soon found herself involved in all aspects of the company. In May 2006, Cindy took full ownership of Crown Royale Ltd., which continues to be a family run business, located in scenic Phillipsburg, NJ. Crown Royale Ltd. continues to bring new, innovative products to professional handlers, groomers and pet owners worldwide. All products are proudly made in the USA with the mission that there is no substitute for quality. Table of Contents About Us . 2 How to use Crown Royale . 3 Grooming Aids . .3 Biovite Shampoos . .4 Shampoos . .5 Conditioners . .6 Finishing, Grooming & Brushing Sprays . .7 Dog Breed & Coat Type . 8-9 Powders . .10 Triple Play Packs . .11 Sporting Dog . .12 Dilution Formulas: Please note when mixing concentrate and storing them for use other than short-term, we recommend mixing with distilled water to keep the formulas as true as possible due to variation in water make-up throughout the USA and international. -

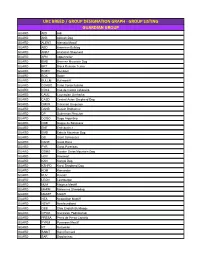

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

Official Standard of the Spinone Italiano General Appearance: the Spinone Has a Distinctive Profile and Soft, Almost-Human Expression

Page 1 of 3 Official Standard of the Spinone Italiano General Appearance: The Spinone has a distinctive profile and soft, almost-human expression. The breed is constructed for endurance. Muscular, vigorous and with powerful bone, the Spinone has a robust build that makes him resistant to fatigue and able to work on almost any terrain; big feet and a two-piece topline give the dog stability on rough ground. The Spinone covers ground efficiently, combining a purposeful, easy trot with an intermittent gallop. A harsh, single coat and thick skin enable the Spinone to negotiate underbrush and endure cold water that would punish any dog not so naturally armored. This versatile pointer is a proficient swimmer and an excellent retriever by nature. The Spinone is patient, methodical and cooperative in the field, and has a gentle demeanor. Size, Proportion, Substance: The height at the withers is 23½ to 27½ inches for males and 22½ to 25½ inches for females. Weight: In direct proportion to size and structure of a dog in working condition. Proportion: His build tends to fit into a square. The length of the body, measured from the point of the shoulder to the point of the buttocks, is equal to or slightly greater than the height at the withers. Substance: The Spinone is a solidly built dog with powerful bone. Head: Long, with muzzle length equal to that of the backskull. The length of the head is equal to 4/10 of the height at the withers; its width measured at the zygomatic arch is less than half of its total length. -

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/As Of: Sept

Kurzform Rasse / Abbreviation Breed Stand/as of: Sept. 2016 A AP Affenpinscher / Monkey Terrier AH Afghanischer Windhund / Afgan Hound AID Atlas Berghund / Atlas Mountain Dog (Aidi) AT Airedale Terrier AK Akita AM Alaskan Malamute DBR Alpenländische Dachsbracke / Alpine Basset Hound AA American Akita ACS American Cocker Spaniel / American Cocker Spaniel AFH Amerikanischer Fuchshund / American Foxhound AST American Staffordshire Terrier AWS Amerikanischer Wasserspaniel / American Water Spaniel AFPV Small French English Hound (Anglo-francais de petite venerie) APPS Appenzeller Sennenhund / Appenzell Mountain Dog ARIE Ariegeois / Arigie Hound ACD Australischer Treibhund / Australian Cattledog KELP Australian Kelpie ASH Australian Shepherd SILT Australian Silky Terrier STCD Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog AUST Australischer Terrier / Australian Terrier AZ Azawakh B BARB Franzosicher Wasserhund / French Water Dog (Barbet) BAR Barsoi / Russian Wolfhound (Borzoi) BAJI Basenji BAN Basst Artesien Normad / Norman Artesien Basset (Basset artesien normand) BBG Blauer Basset der Gascogne / Bue Cascony Basset (Basset bleu de Gascogne) BFB Tawny Brittany Basset (Basset fauve de Bretagne) BASH Basset Hound BGS Bayrischer Gebirgsschweisshund / Bavarian Mountain Hound BG Beagle BH Beagle Harrier BC Bearded Collie BET Bedlington Terrier BBS Weisser Schweizer Schäferhund / White Swiss Shepherd Dog (Berger Blanc Suisse) BBC Beauceron (Berger de Beauce) BBR Briard (Berger de Brie) BPIC Picardieschäferhund / Picardy Shepdog (Berger de Picardie (Berger Picard))