IN the MATTER and in the MATTER BETWEEN and and and and Decision No. a /2002 of the Resource Management Act 1991 of References U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 4 Mana Whenua

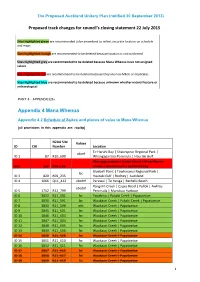

The Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (notified 30 September 2013) Proposed track changes for council’s closing statement 22 July 2015 Sites highlighted green are recommended to be amendend to reflect accurate location on schedule and maps Sites highlighted orange are recommended to be deleted because location is not confirmed Sites highlighted grey are recommended to be deleted because Mana Whenua have not assigned values Sites highlighted red are recommended to be deleted because they are non-Māori or duplicates Sites highlighted blue are recommended to be deleted because unknown whether natural feature or archaeological PART 5 • APPENDICES» Appendix 4 Mana Whenua Appendix 4.2 Schedule of Ssites and places of value to Mana Whenua [all provisions in this appendix are: rcp/dp] NZAA Site Values ID CHI Number Location Te Haruhi Bay | Shakespear Regional Park | abcef ID 1 87 R10_699 Whangaparaoa Peninsula | Hauraki Gulf. Whangaparapara | Aotea Island | Great Barrier ID 2 502 S09_116 Island. | Hauraki Gulf | Auckland City Bluebell Point | Tawharanui Regional Park | bc ID 3 829 R09_235 Hauraki Gulf | Rodney | Auckland ID 4 1066 Q11_412 abcdef Parawai | Te Henga | Bethells Beach Rangiriri Creek | Capes Road | Pollok | Awhitu abcdef ID 5 1752 R12_799 Peninsula | Manukau Harbour ID 6 3832 R11_581 bc Papahinu | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 7 3835 R11_591 bc Waokauri Creek | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 8 3843 R11_599 abc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 9 3845 R11_601 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 10 3846 R11_603 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe -

Hidden Eruptions

HIDDEN ERUPTIONS The Search for AUCKLAND’S VOLCANIC PAST FACT SHEET 02 Fun volcanic facts from the DEtermining VOlcanic Risk in Auckland (DEVORA) Project The Auckland region has a long history of being affected by volcanic eruptions. The region has experienced at least 53 eruptions from the Auckland Volcanic Field (AVF) in the past 200,000 years, and it has been covered by ash from central North Island volcanoes at least 300 times during that period. To determine exactly how often the Auckland region has been affected by eruptions, scientists study ash layers that have been preserved in lake beds. They now think that ash has How can we tell where fallen on Auckland at least once every 600 years! ash layers come from? Scientists have drilled 7 lakes and dried-up lakes looking for ash: Colour /Te Kopua Kai a Hiku, Panmure Basin A white layer = Ash from a larger, more , Pukaki Lagoon, What is volcanic ash? Lake Pupuke /Whakamuhu, distant volcano (e.g. Taupo). Ōrākei Basin, Glover Park When volcanoes erupt, they eject small fragments /Te Hopua a Rangi, and Gloucester Park A black layer = Ash from a smaller, local of broken rock and lava into the air. This material /Te Kopua o Matakerepō. Auckland volcano (e.g. Mt. Wellington). is called tephra. Tephra less than 2mm in size is Onepoto Basin called ash. Ash is so small and light that it is easily picked up and carried by the wind. Ash can travel Location in the core hundreds of kilometres before settling out of the Some large-scale volcanic eruptions are ash cloud and falling to the ground. -

Towards Characterising Rhyolitic Tephra Layers from New

Aberystwyth University Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non-destructive -XRF core scanning Peti, Leonie; Augustinus, Paul C.; Gadd, Patricia S.; Davies, Sarah Published in: Quaternary International DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.039 Publication date: 2019 Citation for published version (APA): Peti, L., Augustinus, P. C., Gadd, P. S., & Davies, S. (2019). Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non-destructive -XRF core scanning. Quaternary International, 514, 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.039 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 11. Oct. 2021 Accepted Manuscript Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non- destructive μ-XRF core scanning Leonie Peti, Paul C. Augustinus, Patricia S. -

March 2013 1 Appendix 3.1: Schedule Of

Draft Auckland Unitary Plan – March 2013 Appendix 3.1: Schedule of Outstanding Natural Features Introduction The following criteria are used to determine the contents of this schedule, and will be used to consider any proposed additions to it. a. the extent to which the landform feature or geological site contributes to the understanding of the geology or evolution of the biota in the region, New Zealand or the earth (includes type localities of rock formations, minerals and fossils) b. the rarity or unusual nature of the site or feature; c. the extent to which the feature or site is an outstanding representative example of the diversity of natural landforms and geological features in Auckland; d. the extent to which the landform or geological feature or site is a component of a recognisable group of geologically associated features; e. the extent to which the landform or geological feature or site contributes to the aesthetic value or visual legibility of the wider natural landscape; f. the community association with, or public appreciation of the values of the feature or site g. the potential value of the feature or site for public education; h. the potential value of the feature or site to provide additional understanding of the geological or biotic history of the region; i. the state of preservation of the feature or site; j. the extent to which a feature or site is associated with an historically important natural event, geologically related industry, or individual involved in earth science research k. the importance of the feature or site to Mana Whenua; l. -

Maori Gardening: an Archaeological Perspective

Maori gardening An archaeological perspective Louise Furey Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10–420 Wellington, New Zealand Cover: Pa, stone row enclosures and puke (garden mounds) at Waikekeno, Wairarapa. Photo: Kevin L. Jones, DOC. © Copyright October 2006, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 0–478–14122–X This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Lynette Clelland and Amanda Todd, and layout by Amanda Todd. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. Maori cultigens 10 2.1 Kumara 10 2.2 Taro 13 2.3 Yam 14 2.4 Gourd 14 2.5 Ti pore 15 2.6 Aute 16 3. Gardening techniques 17 3.1 Garden location 17 3.2 Garden size 17 3.3 Fallowing 18 3.4 Garden preparation 18 3.5 Soil additives 19 4. Limitations to growth of Maori cultigens 20 5. Archaeological evidence of Maori gardening 23 5.1 Stone structures 24 5.1.1 Stone walls and rows 24 5.1.2 Stone alignments 31 5.1.3 Stone heaps 31 5.1.4 Stone mounds 31 5.1.5 Stone facing 34 5.2 Ditches and trenches 34 5.2.1 Steep-slope trenches 36 5.2.2 Trenches on gentle slopes 38 5.2.3 Trench boundary divisions 39 5.2.4 Wetland ditches 40 5.3 Borrow pits 44 5.4 Garden soils 46 5.5 Garden terraces 52 6. -

Annexure a to Procedural Minute 6

Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan Appendix 3.1 Schedule for the Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Owner/ Approral/ Sub#/ Point Name Theme Topic Subtopic Summary Submission Type Support Evidence Comentary Investigate 81 Mt Royal Rd, Mt Albert, and all other lava cave Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the entrances, for inclusion in the SEA schedule [Note - relates to Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features ONFs. Refer to Albert-Eden Local Board Views, Volume 26, page 5716-3481 Auckland Council Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add 30/103]. Local Government no iv Investigate the 'Spring', located under Crystal Motors at 11 Ruru Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the St, Eden Terrace, for inclusion in the SEA schedule [Note - Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features relates to ONFs. Refer to Albert-Eden Local Board Views, Volume 5716-3482 Auckland Council Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add 26, page 30/103]. Local Government no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Include volcanic features in former outlying district such as Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Franklin within the PAUP including Pukekohe Hill, Puni Mountain, 4485-11 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add Pukekohe East crater. Key Stakeholder no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Include Pukekohe Hill and Puni Mountain as outstanding natural 4485-13 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add features. Key Stakeholder no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Apply V1 and V2 overlays to volcanic reserves and surrounding 4485-21 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add Includeareas. -

Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan

Volcanic Viewshafts and height sensitive areas rules - Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts survey coordinates Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan Summary of Decisions Requested Sub#/ Point Name Theme Topic Subtopic Summary Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-20 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Protect views between Maunga. Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-152 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Retain all the viewshafts listed Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-153 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Add additional viewshafts which protect iconic explosion craters Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-154 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Add viewshaft to protect views to Panmure Basin from the top of Mt Wellington Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-155 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Add viewshaft to protect views to Orakei Basin from Kepa Road Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-156 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Add viewshaft to protect views to Orakei Basin from Upland Road crest. Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-157 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Add viewshaft to protect views to Rangitoto from Lucerne Road, Remuera Volcanic Viewshafts and height Appendix 3.3 - Volcanic view shafts 93-158 Geoscience Society of New Zealand sensitive areas rules survey coordinates Add viewshaft to protect views to Mt Wellington from Lunn Ave-Abbotts Way intersection. -

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1 Chapter 6 — Heritage CONTENTS This chapter is presented as follows: 6.1 Introduction This outlines how heritage is defined and the statutory context of this chapter. 6.2 Resource Management Issues This outlines the significant resource management issues relating to heritage resources within the City. 6.3 Objectives This sets out the overall desired environmental outcomes for the heritage resources of the City. 6.4 Policies This describes how Council intends to ensure that the objectives for the City’s heritage resources are met. An explanation of the policies is given. A summary of the range of methods that are used to implement each policy is also included. 6.5 Heritage Strategy The strategy summarises the overall approach to managing the City’s natural and cultural heritage resources. 6.6 Implementation This broadly describes the regulatory and non-regulatory methods used to implement the policies for the management of the City’s heritage resources. 6.7 Anticipated Environmental Results This outlines the environmental outcomes anticipated from the implementation of the policies and methods as set out in the Heritage Chapter. 6.8 Procedures for Monitoring This outlines how Council will monitor the effectiveness of the Heritage provisions. Manukau Operative District Plan 2002 Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 2 6.9 Rules — Activities This sets out in an Activity Table the permitted and discretionary activities for the scheduled heritage resources of the City. 6.10 Rules – Matters for Control: Controlled Activities 6.11 -

Landscape Environmental Baseline Report Final

AUCKLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PROPOSED SECOND RUNWAY LANDSCAPE BASELINE REPORT Client: Auckland International Airport Limited Project: Proposed Second Runway Report: Landscape Baseline Report Status: Final Date: 23 October 2015 Author: Gavin Lister and Matthew Jones Isthmus PO Box 90 366 Auckland 1142 +64 9 309 7281 [email protected] 151023_3346_GL_AIAL Second Runway_Landscape and Urban Design Baseline Report_p.2 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 7 ANALYSIS OF EXISTING LANDSCAPE .................................................................................... 8 ‘Northern Area of Influence’ ............................................................................................... 8 Northern Landscape ........................................................................................................... 8 Natural features ............................................................................................................................ 8 Activities and aesthetics ............................................................................................................... 8 History ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Future airport urban centre ......................................................................................................... -

Abstract Template for the Lasi Iii Conference

Geoscience Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Publication 131A Cerro Chivo Laguna Azul Abstract Volume of the Laguna Potrok Aike Fourth International Maar Conference 3IMC - ARGENTINA A Multidisciplinary Congress on Monogenetic Volcanism Edited by Kate Arentsen, Károly Németh, Elaine Smid Badacsony Tihany Filakovo 2IMC - HUNGARY - SLOVAKIA -GERMANY Pulvermaar Dauner Maare Auckland, New Zealand 20-24 February 2012 Eichholzmaar 1IMC - GERMANY Fourth International Maar Conference a multidisciplinary congress on monogenetic volcanism Auckland, New Zealand 20 – 24 February 2012 ABSTRACTS VOLUME Edited by Kate Arentsen, Károly Németh, Elaine Smid Geoscience Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Publication 131A ISBN 978-1-877480-15-7 ISSN Online 2230-4495 ISSN Print 2230-4487 Previous IMCs International Maar Conference Daun, Germany, 2000 Second International Maar Conference Lajosmizse, Hungary, 2004 Third International Maar Conference Malargüe, Argentina, 2009 Conference Supporters International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior International Association of Sedimentologists Geoscience Society of New Zealand The University of Auckland Massey University Institute of Earth Science and Engineering Earthquake Commission Elsevier Springer Villa Maria Estate Epic Beer Organizing Committee Károly Németh and Ian EM Smith (Co-Chairs) Members: Kate Arentsen, Shane Cronin, Jan Lindsay, Janet Simes, Elaine Smid Scientific Advisory Group Georg Buechel, Kathy Cashman, Shane Cronin, Gonca Gençalioğlu Kuşcu, Guido Giordano, Stephan Kurszlaukis, Jan Lindsay, Volker Lorenz, Joan Marti, Károly Németh, Corina Risso, Hetu Sheth, Claus Siebe, Ian EM Smith, Young Kwan Sohn, Greg Valentine, James White, Bernd Zimanowski, Bernd Zolitschka IAVCEI – CMV/CVS – IAS 4IMC Conference Auckland, New Zealand, 2012 Preface We extend our warmest welcome to delegates of the Fourth International Maar Conference (4IMC) and look forward to hosting you in Auckland, New Zealand. -

Pukekohe Heritage Survey Appendices

Pukekohe Heritage Survey FINAL Appendix 2: Timeline 1 Pukekohe Heritage Survey- Time line PUKEKOHE: TIMELINE Overview This timeline captures an overview of key events of significance in the wider historical development of Pukekohe, Pukekohe East, Paerata, Puni, Helvetia and Buckland. It is not intended or possible to capture all events of historical interest. The timeline should be read as a companion to Appendix 1: Historic Context Statement which often provides more elaborate details in relation to an event. The timeline details set out below are derived from content within the Historic Context Statement (HCS): Appendix 1, with relevant references set out within the HCS report references list. Information is also derived from the Auckland Libraries online ‘Manukau’s Journey’ timeline in many instances.1 NB: Images of the events may not relate exactly to how a place appears at the corresponding date, and often relates to a later point in time. The images are illustrative only and serve to reinforce the text. Images are not set out unless there is a relevant known image. DATE(S) EVENT THEME(S) The Crown purchases a large block of land (Pukekohe Block No. 1) Land and People 1843 from Ngati Te Ata, stretching from Karaka through to Pukekohe, as far south as the Waikato River. The Karaka portion of land is Building the Place surveyed and subdivided soon afterwards. Ngati Haua, Ngati Tamaoho and Ngati Mahanga dispute Ngati Te Ata's right to sell parts of the block. Mid.1850s European settlement of the area begins; in particular, in the area Land and People today called Pukekohe East. -

Archaeological Assessment of Self Farm / Crater Hill Papatoetoe, Auckland

Archaeological Assessment of Self Farm / Crater Hill Papatoetoe, Auckland 1 September 2015 Prepared for: Self Family Trust 1 Tidal Road Papatoetoe AUCKLAND Prepared by: Geometria Limited 3/3 Margaret Street Freemans Bay Auckland 1045 Self Farm Archaeological Assessment Quality Information Document: Self Farm Archaeological Assessment Ref: 2015-13 Date: 1 September 2015 Prepared by: Russell Gibb Revision History Revision Revision Date Details Authorized Name Draft 13 July 2015 Drafted Gibb Minor edits 13 July 2015 Reviewed by Carpenter Final Draft 16th July Distributed Gibb Corrections 1 September 2015 Distribution Gibb © GEOMETRIA Limited 2015 The information contained in this document produced by GEOMETRIA Limited is solely for the use of the Client identified on the cover sheet for the purpose for which it has been prepared and GEOMETRIA Limited undertakes no duty to nor accepts any responsibility to any third party who may rely upon this document. All rights reserved. No section or element of this document may be removed from this document, reproduced, electronically stored or transmitted in any from without the written permission of GEOMETRIA Limited. File ref.: 2015/Self_Family_Trust/20150713_Self_Farm_Assessment Geometria 2015 2 Self Farm Archaeological Assessment CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Location ........................................................................................................................