Mana Whenua Cultural Values of the Proposed Second Runway Summary Report Prepared for Auckland International Airport Ltd by Chetham Consulting Ltd December 2015 V.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 4 Mana Whenua

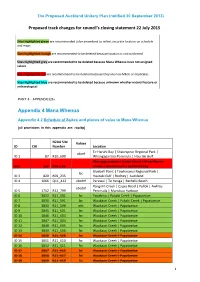

The Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (notified 30 September 2013) Proposed track changes for council’s closing statement 22 July 2015 Sites highlighted green are recommended to be amendend to reflect accurate location on schedule and maps Sites highlighted orange are recommended to be deleted because location is not confirmed Sites highlighted grey are recommended to be deleted because Mana Whenua have not assigned values Sites highlighted red are recommended to be deleted because they are non-Māori or duplicates Sites highlighted blue are recommended to be deleted because unknown whether natural feature or archaeological PART 5 • APPENDICES» Appendix 4 Mana Whenua Appendix 4.2 Schedule of Ssites and places of value to Mana Whenua [all provisions in this appendix are: rcp/dp] NZAA Site Values ID CHI Number Location Te Haruhi Bay | Shakespear Regional Park | abcef ID 1 87 R10_699 Whangaparaoa Peninsula | Hauraki Gulf. Whangaparapara | Aotea Island | Great Barrier ID 2 502 S09_116 Island. | Hauraki Gulf | Auckland City Bluebell Point | Tawharanui Regional Park | bc ID 3 829 R09_235 Hauraki Gulf | Rodney | Auckland ID 4 1066 Q11_412 abcdef Parawai | Te Henga | Bethells Beach Rangiriri Creek | Capes Road | Pollok | Awhitu abcdef ID 5 1752 R12_799 Peninsula | Manukau Harbour ID 6 3832 R11_581 bc Papahinu | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 7 3835 R11_591 bc Waokauri Creek | Pukaki Creek | Papatoetoe ID 8 3843 R11_599 abc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 9 3845 R11_601 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe ID 10 3846 R11_603 bc Waokauri Creek | Papatoetoe -

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule

Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule [rcp/dp] Introduction The factors in B4.2.2(4) have been used to determine the features included in Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule, and will be used to assess proposed future additions to the schedule. ID Name Location Site type Description Unitary Plan criteria 2 Algies Beach Algies Bay E This site is one of the a, b, g melange best examples of an exposure of the contact between Northland Allocthon and Miocene Waitemata Group rocks. 3 Ambury Road Mangere F A complex 140m long a, b, c, lava cave Bridge lava cave with two d, g, i branches and many well- preserved flow features. Part of the cave contains unusual lava stalagmites with corresponding stalactites above. 4 Anawhata Waitākere A This locality includes a a, c, e, gorge and combination of g, i, l beach unmodified landforms, produced by the dynamic geomorphic processes of the Waitakere coast. Anawhata Beach is an exposed sandy beach, accumulated between dramatic rocky headlands. Inland from the beach, the Anawhata Stream has incised a deep gorge into the surrounding conglomerate rock. 5 Anawhata Waitākere E A well-exposed, and a, b, g, l intrusion unusual mushroom-shaped andesite intrusion in sea cliffs in a small embayment around rocks at the north side of Anawhata Beach. 6 Arataki Titirangi E The best and most easily a, c, l volcanic accessible exposure in breccia and the eastern Waitākere sandstone Ranges illustrating the interfingering nature of Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in part 1 Schedule 6 Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Schedule the coarse volcanic breccias from the Waitākere Volcano with the volcanic-poor Waitematā Basin sandstone and siltstones. -

A/HRC/18/35/Add.4 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/18/35/Add.4 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 May 2011 Original: English Human Rights Council Eighteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya Addendum The situation of Maori people in New Zealand∗ Summary In the present report, which has been updated since the advance unedited version was made public on 17 February 2011, the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples examines the situation of Maori people in New Zealand on the basis of information received during his visit to the country from 18-23 July 2010 and independent research. The visit was carried out in follow-up to the 2005 visit of the previous Special Rapporteur, Rodolfo Stavenhagen. The principal focus of the report is an examination of the process for settling historical and contemporary claims based on the Treaty of Waitangi, although other key issues are also addressed. Especially in recent years, New Zealand has made significant strides to advance the rights of Maori people and to address concerns raised by the former Special Rapporteur. These include New Zealand’s expression of support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, its steps to repeal and reform the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act, and its efforts to carry out a constitutional review process with respect to issues related to Maori people. Further efforts to advance Maori rights should be consolidated and strengthened, and the Special Rapporteur will continue to monitor developments in this regard. -

Immigration During the Crown Colony Period, 1840-1852

1 2: Immigration during the Crown Colony period, 1840-1852 Context In 1840 New Zealand became, formally, a part of the British Empire. The small and irregular inflow of British immigrants from the Australian Colonies – the ‘Old New Zealanders’ of the mission stations, whaling stations, timber depots, trader settlements, and small pastoral and agricultural outposts, mostly scattered along the coasts - abruptly gave way to the first of a number of waves of immigrants which flowed in from 1840.1 At least three streams arrived during the period 1840-1852, although ‘Old New Zealanders’ continued to arrive in small numbers during the 1840s. The first consisted of the government officials, merchants, pastoralists, and other independent arrivals, the second of the ‘colonists’ (or land purchasers) and the ‘emigrants’ (or assisted arrivals) of the New Zealand Company and its affiliates, and the third of the imperial soldiers (and some sailors) who began arriving in 1845. New Zealand’s European population grew rapidly, marked by the establishment of urban communities, the colonial capital of Auckland (1840), and the Company settlements of Wellington (1840), Petre (Wanganui, 1840), New Plymouth (1841), Nelson (1842), Otago (1848), and Canterbury (1850). Into Auckland flowed most of the independent and military streams, and into the company settlements those arriving directly from the United Kingdom. Thus A.S.Thomson observed that ‘The northern [Auckland] settlers were chiefly derived from Australia; those in the south from Great Britain. The former,’ he added, ‘were distinguished for colonial wisdom; the latter for education and good home connections …’2 Annexation occurred at a time when emigration from the United Kingdom was rising. -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Hidden Eruptions

HIDDEN ERUPTIONS The Search for AUCKLAND’S VOLCANIC PAST FACT SHEET 02 Fun volcanic facts from the DEtermining VOlcanic Risk in Auckland (DEVORA) Project The Auckland region has a long history of being affected by volcanic eruptions. The region has experienced at least 53 eruptions from the Auckland Volcanic Field (AVF) in the past 200,000 years, and it has been covered by ash from central North Island volcanoes at least 300 times during that period. To determine exactly how often the Auckland region has been affected by eruptions, scientists study ash layers that have been preserved in lake beds. They now think that ash has How can we tell where fallen on Auckland at least once every 600 years! ash layers come from? Scientists have drilled 7 lakes and dried-up lakes looking for ash: Colour /Te Kopua Kai a Hiku, Panmure Basin A white layer = Ash from a larger, more , Pukaki Lagoon, What is volcanic ash? Lake Pupuke /Whakamuhu, distant volcano (e.g. Taupo). Ōrākei Basin, Glover Park When volcanoes erupt, they eject small fragments /Te Hopua a Rangi, and Gloucester Park A black layer = Ash from a smaller, local of broken rock and lava into the air. This material /Te Kopua o Matakerepō. Auckland volcano (e.g. Mt. Wellington). is called tephra. Tephra less than 2mm in size is Onepoto Basin called ash. Ash is so small and light that it is easily picked up and carried by the wind. Ash can travel Location in the core hundreds of kilometres before settling out of the Some large-scale volcanic eruptions are ash cloud and falling to the ground. -

Mauri Monitoring Framework. Pilot Study on the Papanui Stream

Te Hā o Te Wai Māreparepa “The Breath of the Rippling Waters” Mauri Monitoring Framework Pilot Study on the Papanui Stream Report Prepared for the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council Research Team Members Brian Gregory Dr Benita Wakefield Garth Harmsworth Marge Hape HBRC Report No. SD 15-03 Joanne Heperi HBRC Plan No. 4729 2 March 2015 (i) Ngā Mihi Toi tü te Marae a Tane, toi tü te Marae a Tangaroa, toi tü te iwi If you preserve the integrity of the land (the realm of Tane), and the sea (the realm of Tangaroa), you will preserve the people as well Ka mihi rā ki ngā marae, ki ngā hapū o Tamatea whānui, e manaaki ana i a Papatūānuku, e tiaki ana i ngā taonga a ō tātau hapu, ō tātau iwi. Ka mihi rā ki ngā mate huhua i roro i te pō. Kei ngā tūpuna, moe mai rā, moe mai rā, moe mai rā. Ki te hunga, nā rātau tēnei rīpoata. Ki ngā kairangahau, ka mihi rā ki a koutou eū mārika nei ki tēnei kaupapa. Tena koutou. Ko te tūmanako, ka ora nei, ka whai kaha ngāwhakatipuranga kei te heke mai, ki te whakatutuki i ngā wawata o kui o koro mā,arā, ka tū rātau hei rangatira mō tēnei whenua. Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa Thanks to the many Marae, hapū, from the district of Tamatea for their involvement and concerns about the environment and taonga that is very precious to their iwi and hapū. Also acknowledge those tūpuna that have gone before us. -

Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 with DATA for the SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA

Auckland plan targets: monitoring report 2015 WITH DATA FOR THE SOUTHERN INITIATIVE AREA Auckland Plan Targets: Monitoring Report 2015 With Data for the Southern Initiative Area March 2016 Technical Report 2016/007 Auckland Council Technical Report 2016/007 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-0-9941350-0-1 (Print) ISBN 978-0-9941350-1-8 (PDF) This report has been peer reviewed by the Peer Review Panel. Submitted for review on 26 February 2016 Review completed on 18 March 2016 Reviewed by one reviewer. Approved for Auckland Council publication by: Name: Dr Lucy Baragwanath Position: Manager, Research and Evaluation Unit Date: 18 March 2016 Recommended citation Wilson, R., Reid, A and Bishop, C (2016). Auckland Plan targets: monitoring report 2015 with data for the Southern Initiative area. Auckland Council technical report, TR2016/007 Note This technical report updates and replaces Auckland Council technical report TR2015/030 Auckland Plan Targets: monitoring report 2015 which does not contain data for the Southern Initiative area. © 2016 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council's copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. -

Coastal Map Series 3

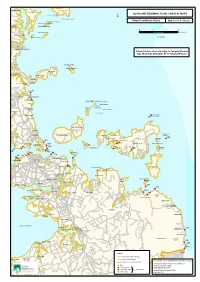

HEPBURN CREEK KAWAU ISLAND ALGIES BAY BEEHIVE ISLAND CHALLENGER ISLAND MOTUKETEKETE ISLAND MOTUREKAREKA ISLAND PUKAPUKA MOTUTARA ISLAND MOTUORA ISLAND MAHURANGI WEST 1 TE HAUPA ISLAND WENDERHOLM WAIWERA MAHURANGI IS OREWA WOODED ISLAND TIRITIRI MATANGI ISLAND REGIONAL PARK SILVERDALE MATAKATIA BAY BIG MANLY ARKLES BAY STILLWATER WADE HEADS 21 LONG BAY OKURA MARINE RESERVE LONG BAY REGIONAL PARK MOTUHOROPAPA ISLAND THE NOISES TORBAY DAVID ROCKS OTATA ISLAND RAKINO IS. ZENO ROCK BROWNS BAY MARIA ISLAND ALBANY THE NOISES HORUHORU ROCK MURRAYS BAY 173(Gannet Rock) MAIRANGI BAY MOTUTAPU ISLAND MILFORD TARAHIKI IS TAKAPUNA RANGITOTO ISLAND ONEROA PALM BEACH (Shag Is) BEACH HAVEN BLACKPOOL 115 SURFDALE ONETANGI PAKATOA ISLAND 167 OSTENDWAIHEKE ISLAND 94 WAIHEKE ISLAND NORTHCOTE 168 FRENCHMANS CAP DOMAIN BAYSWATER MOTUIHE IS. 169 42 PAPAKOHATU IS 89OMIHA ROTOROA (Crusoe Is) 106 ISLAND 41 DEVONPORTHEAD 170 46 64 BROWNS IS. 172 (Motukorea) 44 HERNE BAY 66 KOHIMARAMA 172 ST HELIERS AUCKLAND ORAKEI PT. CHEVALIER DOMAIN GLENDOWIE TAHUNA BEACH WATERVIEW GLEN INNES PONUI ISLAND REMUERA 74 MOTUKARAKA IS (Chamberlins Is) PARKMARAETAI BEACHLANDS FARM COVE PANMURE HOWICK PANMURE BASIN BEACHLANDS PAKIHI ISLAND MT WELLINGTON DUDER PARK 126 PAKURANGA ONEHUNGA BLOCKHOUSE BAY 130 176 NIMT AMBURY REGIONAL PARK 174 OTAHUHU EAST TAMAKI WHITFORD 175 REGIONAL MANGERE SEWAGE PARK KAWAKAWA BAY PUKETUTU ISLAND MANGERE ORERE POINT ORERE TAPAPAKANGA REGIONAL PARK CLEVEDON PUHINUI MATINGARAHI WIROA IS. MANUREWA MANUKAU HARBOUR WEYMOUTH TAKANINI WAHARAU 177 WATTLE DOWNSCONIFER GROVE REGIONAL PARK PAPAKURA WHAREKAWA HUNUA RANGES REGIONAL PARK 178 ELLETS BEACH SEAGROVE 179 KARAKA 180 DRURY KAIAUA KINGSEAT CLARKS BEACH WAIAU PA GLENBROOK BEACH. -

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Māori Tourism Experiences

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Māori tourism experiences aucklandnz.com Tāmaki Makaurau A place desired by many Tāmaki Herenga Waka The place where many canoes gather These are the Māori names given to Auckland. They speak of our diverse landscapes, beautiful harbours and fertile soils. They speak of the coming together of different iwi (tribes) to meet and trade. Today, people from all over the world visit Tāmaki Makaurau for the same reasons – to experience our natural beauty and unique Māori culture. In the spirit of manaakitanga – hospitality, generosity and openness of spirit – we welcome our visitors as guests. Discover this spirit as you connect with the people, land Te Kotūiti Tuarua – Ngāti Paoa and stories that have shaped our region. Māori tourism experiences in the Auckland region Goat Island Matakana Great Barrier Island NORTH AUCKLAND HAURAKI GULF AND ISLANDS Tiritiri Matangi Island Whangaparaoa Rangitoto Island WEST AUCKLAND Waiheke Island Muriwai Beach AUCKLAND CENTRAL Piha Beach Hunua Ranges EAST Awhitu Peninsula AUCKLAND SOUTH AUCKLAND AUCKLAND HAURAKI GULF NORTH CENTRAL AND ISLANDS AUCKLAND Auckland Ghost Tours Hike Bike Ako Waiheke Island Pakiri Beach Horse Rides Kura Gallery Pōtiki Adventures Te Hana Te Ao Marama Okeanos Aotearoa Te Haerenga Guided Walks Tāmaki Hikoi Waiheke Horseworx Tāmaki Paenga Hira (Auckland War Memorial Museum) The Poi Room TIME Unlimited Tours Toru Tours Waka Quest Whanau Marama Māori Experiences Auckland Hike Bike Ako Ghost Tours Waiheke Island A lantern lit walking tour in Hike Bike Ako Waiheke Island – Walk Auckland CBD and Symonds and E-Cycle with Māori. We offer Street Cemetery visiting the most fully guided walking and electric historical streets with beguiling bicycle tours on Waiheke Island. -

Ngāiterangi Treaty Negotiations: a Personal Perspective

NGĀITERANGI TREATY NEGOTIATIONS: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE Matiu Dickson1 Treaty settlements pursuant to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi can never result in a fair deal for Māori who seek justice against the Crown for the wrongs committed against them. As noble the intention to settle grievances might be, at least from the Crown’s point of view, my experience as an Iwi negotiator is that we will never receive what we are entitled to using the present process. Negotiations require an equal and honest contribution by each party but the current Treaty settlements process is flawed in that the Crown calls the shots. To our credit, our pragmatic nature means that we accept this and move on. At the end of long and sometimes acrimonious settlement negotiations, most settlements are offered with the caveat that as far as the Crown is concerned, these cash and land compensations are all that the Crown can afford so their attitude is “take it or leave it”. If Māori do not accept what is on offer, then they have to go to the back of the queue. The process is also highly politicised so that successive Governments are not above using the contentious nature of settlements for their political gain, particularly around election time. To this end, Governments have indicated that settlements are to be concluded in haste, they should be full and final and that funds for settlements are capped. These are hardly indicators of equal bargaining power and good faith, which are the basic principles of negotiation. As mentioned, the ‘negotiations’ are not what one might consider a normal process in that, normally, parties are equals in the discussions. -

Towards Characterising Rhyolitic Tephra Layers from New

Aberystwyth University Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non-destructive -XRF core scanning Peti, Leonie; Augustinus, Paul C.; Gadd, Patricia S.; Davies, Sarah Published in: Quaternary International DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.039 Publication date: 2019 Citation for published version (APA): Peti, L., Augustinus, P. C., Gadd, P. S., & Davies, S. (2019). Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non-destructive -XRF core scanning. Quaternary International, 514, 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.06.039 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 11. Oct. 2021 Accepted Manuscript Towards characterising rhyolitic tephra layers from New Zealand with rapid, non- destructive μ-XRF core scanning Leonie Peti, Paul C. Augustinus, Patricia S.