Fortescue Marsh Management Strategy 2018-2024 Sept 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Question on Notice

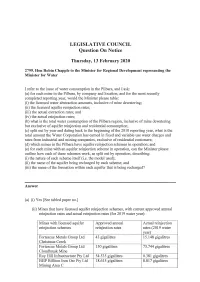

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Question On Notice Thursday, 13 February 2020 2799. Hon Robin Chappie to the Minister for Re ional Development representing the Minister for Water I refer to the issue of water consumption in the Pilbara, and I ask: (a) for each mine in the Pilbara, by company and location, and for the most recently completed reporting year, would the Minister please table: (i) the licensed water abstraction amounts, inclusive of mine dewatering; (ii) the licensed aquifer reinjection rates; (iii) the actual e traction rates; and (i ) the actual reinjection rates; (b) what is the total water consumption of the Pilbara region, inclusive of mine dewatering but exclusive of aquifer reinjection and residential consumption; (c) split out by year and dating back to the beginning of the 2010 reporting year, what is the total amount the Water Corporation has earned in fixed and variable use water charges and rates from industrial and mining companies, exclusi e of residential customers; (d) which mines in the Pilbara have aquifer reinjection schemes in operation; and (e) for each ine with an aquifer reinjection scheme in operation, can the Minister please outline how each of these schemes work, as split out by operation, describing: (i) the nature of each scheme itself (i.e. the model used); (ii) the name of the aquifer being recharged by each scheme; and (iii) the name of the formation within each aquifer that is being recharged? Answer (a) (i) Yes [See tabled paper no.] (ii) Mines that have licensed aquifer reinjection schemes, with current -

Welcome to Cloudbreak

Welcome to Cloudbreak This booklet provides you with the information needed to help make your stay at Cloudbreak more pleasant. Please take the time to read through the information before arriving on site. FEBRUARY 2009 Table of Contents Welcome Message ........................................................................................... 1 Foreword ..................................................................................................... 1 PART ONE: Before you depart ......................................................................... 2 The Pilbara ....................................................................................................... 3 Fortescue Metals Group Limited ...................................................................... 3 Cloudbreak....................................................................................................... 3 Packed and ready to go .................................................................................... 4 At the departure lounge ............................................................................... 4 Parking at Perth Airport ............................................................................... 5 Staying in touch ............................................................................................... 5 On Arrival ......................................................................................................... 5 At the Airstrip .............................................................................................. -

Rutila Resources Ltd ASX

Rutila Resources Ltd ASX : RTA For personal use only Investor Presentation 27 November 2013 Rutila Resources Ltd – Disclaimer This Presentation has been prepared by Rutila Resources Ltd (ABN 139 886 187) (Rutila or the Company). This Presentation contains summary information about Rutila and its subsidiaries (Rutila Group) and their activities current as at the date of this Presentation. The information in this Presentation is of general background and does not purport to be complete or to comprise all the information that a shareholder or potential investor in Rutila may require in order to determine whether to deal in Rutila shares. It should be read in conjunction with Rutila Group’s other periodic and continuous disclosure announcements lodged with the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), which are available at www.asx.com.au. This document is not a prospectus or a product disclosure statement under the Corporations Act (Cth) 2001 (Corporations Act) and has not been lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). Not investment or financial product advice This Presentation is for information purposes only and is not financial product or investment advice or a recommendation to acquire Rutila shares and has been prepared without taking into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of individuals. Before making an investment decision, prospective investors should consider the appropriateness of the information having regard to their own objectives, financial situation and needs and seek financial, legal and taxation advice appropriate to their jurisdiction. Rutila is not licensed to provide financial product advice in respect of Rutila shares. Cooling off rights do not apply to the acquisition of Rutila shares. -

20130627 D107351

Ref: O10_0347 Submission to the Economic Regulation Authority – Floor and ceiling costs proposed by The Pilbara Infrastructure (TPI) 11 June 2013 FLOOR AND CEILING COSTS PROPOSED BY THE PILBARA INFRASTRUCTURE (TPI) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 2 2. CONTEXT AND PURPOSE ................................................................................................................... 2 1. Context .......................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Purpose........................................................................................................................................... 3 3. REQUIREMENTS OF THE CODE ........................................................................................................... 4 4. COMMENTS ON COSTS PROPOSED BY TPI ....................................................................................... 5 1. TPI failure to provide costs for proposed access ................................................................... 5 2. TPI failure to provide Costing Model or supporting information ......................................... 5 3. Factors to be considered in an assessment of costs ............................................................. 6 5. BROCKMAN’S ASSESSMENT OF COSTS FOR THE ROUTE .................................................................. 7 6. COMPARISON -

Working Together. Delivering Results. ABN 57 002 594 872 I 2015 Annual Report the YEAR at a GLANCE

Working together. Delivering results. ABN 57 002 594 872 I 2015 Annual Report THE YEAR AT A GLANCE SAFETY Operating cost Total Recordable 5.1 Injury Frequency Rate (TRIFR) 21% 165.4 Revenue million tonnes shipped for FY15 US$8.6 13% billion Aboriginal employment achieved Fifth berth at Herb Elliott Port Commissioned March 2015 Fortescue River A$ Gas Pipeline 1.8 billion construction completed Contracts to Aboriginal companies and JVs 17.3 2.4 billion tonnes Ore Reserves Mineral Resources ABOUT FORTESCUE Overview 3 Fortescue Metals Group is a global leader in the iron ore industry, recognised for its culture, innovation and industry-leading development of world class infrastructure and mining assets in the Pilbara, Western Australia. Since it was founded in 2003, Fortescue has discovered and developed significant iron ore deposits and constructed some Operating and Financial Review 19 of the largest mines in the world. The Chichester Hub, which includes the Cloudbreak and Christmas Creek mines, is located in the Chichester Ranges, and produces more than 90 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of iron ore and an additional six mtpa from Fortescue’s joint venture with BC Iron. The Solomon Hub is located in the Hamersley Ranges, and includes Reserves and Resources 33 the Firetail and Kings Valley mines which produce in excess of 70 mtpa. Fortescue has constructed world class facilities at its five berth Herb Elliott Port in Port Hedland, and operates the fastest, heavy haul railway in the world with up to 42 tonne axle load capacity over 620km of track, including 12 bridges. -

Integrated Rail Network Closure Plan

Report Integrated Rail Network Closure Plan Long Term Mine Planning 7 June 2018 R-PL-EN-0041 Rev 0 CLOSURE GUIDELINE CHECKLIST Report This closure plan addresses the progressive rehabilitation and closure of rail infrastructure projects associated with the Railway and Port (The Pilbara Infrastructure Pty Ltd) Agreement Act 2004. In the absence of regulatory guidelines for inland infrastructure projects, this closure plan follows the report structure described within the Guidelines for Preparing Mine Closure Plans May 2015 published by the Government of Western Australia Department of Mines and Petroleum (now the Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety) and Environmental Protection Authority. The closure of mining operations, including quarries, is not within the scope of this closure plan. Closure Plan (CP) checklist Y/N Page Comments 1 Has the Checklist been endorsed by a senior Y 2 Report has been endorsed using representative within the tenement holder/operating standard Fortescue processes. company? Public Availability 2 Are you aware that from 2015 all CPs will be made N/A This report is not subject to mine closure publicly available? conditions under the Mining Act. 3 Is there any information in the CP that should not be N publicly available? 4 If “Yes” to Q3, has confidential information been N/A submitted in a separate document/section? Cover Page, Table of Contents 5 Does the CP cover page include: Y 1 This report is provided for information • Project Title only. • Company Name • Contact Details (including telephone numbers and email addresses) • Document ID and version number • Date of submission (needs to match the date of this checklist) Scope and Purpose 6 State why the CP is submitted Y 11 This plan has been provided to support the Eliwana Rail Project Public Environmental Review. -

17 August 2018 the Companies Officer Australian Securities

17 August 2018 The Companies Officer Australian Securities Exchange Ltd Level 40, Central Park 152-158 St Georges Terrace Perth WA 6000 Dear Madam or Sir Fortescue Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources Update: Operating Properties Fortescue Metals Group (ASX:FMG, Fortescue) presents the Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources statement for its Hematite and Magnetite properties at 30 June 2018. Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources are reported in accordance with the Australasian Code for Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves, December 2012 (the JORC Code) as required by the Australian Securities Exchange. The annual summary will be included in Fortescue’s 2018 Annual Report and should be read in conjunction with the enclosed supporting technical information (Attachment 1 – Hematite Ore Reserve and Mineral Resources Report and Attachment 2 – Magnetite Ore Reserve and Mineral Resources Report). Hematite Ore Reserve and Mineral Resource – Operating Properties Reporting 30 June 2018 30 June 2017 Basis Million tonnes Fe% Million tonnes Fe% Ore Reserves (Dry Product) 2,250 57.4 2,191 57.2 Mineral Resources (Dry In-Situ) 6,122 56.4 5,279 56.0 Operating properties include the Chichester and Solomon Hubs as well as the Eliwana deposit (part of the Western Hub) following its transfer from development properties. The maiden reserve for Eliwana is at a 60.1 per cent iron grade. Ore deposit types include Bedded Iron (BID), Channel Iron (CID) and Detrital Iron (DID) mineralisation. The Iron Bridge Magnetite project is unchanged from the 2017 release, with the feasibility study continuing with a focus on optimising the commercialisation of mining, processing and infrastructure. -

Ecohydrological Conceptualisation of the Fortescue Marsh Region

REPORT Ecohydrological Conceptualisation of the Fortescue Marsh Region Prepared for BHP Billiton Iron Ore September 2015 This report has been prepared solely for the purposes of informing environmental impact assessment pursuant to the Environmental Protection Act 1986 (WA) and Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) and is not intended for use for any other purpose. No representation or warranty is given that project development associated with any or all of the disturbance indicated in this report will actually proceed. As project development is dependent upon future events , the outcome of which is uncertain and cannot be assured, actual development may vary materially from this report. Ecohydrological Conceptualisation of the Fortescue Marsh Region This document has been prepared for the benefit of BHP Billiton Iron Ore. No liability is accepted by this company or any employee or sub-consultant of this company with respect to its use by any other person. This disclaimer shall apply notwithstanding that the report may be made available to other persons for an application for permission or approval to fulfil a legal requirement. QUALITY STATEMENT PROJECT MANAGER PROJECT TECHNICAL LEAD Tracy Schwinkowski Milo Simonic PREPARED BY Milo Simonic ………………………………............... 02/09/2015… CHECKED BY Johan van Rensburg ………………………………............... 02/09/2015… REVIEWED BY Gary Clark ………………………………............... 02/09/2015… APPROVED FOR ISSUE BY Milo Simonic ………………………………............... 02/09/2015… PERTH 41 Bishop Street, -

Civil Projects

Civil Projects DOWNER’S MINING CIVIL PROJECTS DIVISION PROVIDES A TOTAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT SERVICE FOR THE ENGINEERING DESIGN, PROCUREMENT AND CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT OF MINE-SITE INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS THROUGHOUT WESTERN AUSTRALIA. PROJECT CAPABILITIES ■ mine workshop facilities; ■ diesel fuel bulk storage facilities; ■ lubrication storage including workshop reticulation; ■ administration facilities including underground service reticulation; ■ explosives storage facilities, bulk ammonium nitrate and emulsion; ■ heavy vehicle wash-facilities and associated oily-water processing ponds; ■ mine access roads and haul roads; ■ airstrips; ■ tailing storage facilities; and ■ mine development bulk earthworks. Managed by personnel with a wealth of experience in both the mining and civil construction industries, Downer is able to offer turnkey solutions for both greenfield and brownfield projects, and efficiently manage subcontractors for specialist work using its own proven Roy Hill Iron Ore Mine systems and controls. The role undertaken by us on a typical project includes: Annual targets for increased participation ■ management of engineering FORTESCUE METALS design and documentation for civil, by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander GROUP, CLOUDBREAK MINE structural, mechanical, electrical and people are set across the business. hydraulic works; Cloudbreak Wash-pad ($4M) ■ procurement of materials and ROY HILL IRON ORE, ■ dual heavy vehicle wash-pad facility; equipment using the extensive ROY HILL MINE ■ associated sediment and treatment resources -

Mammoet World Getting to the Mine

GETTING TO THE MINE ON TIME Three draglines, two continents, one objective Issue 13 | 2014 MAMMOET WORLD 67 ine sites are often situated at remote locations. Getting a dragline there involves dealing with a variety of circumstances, such as negotiating M gravel or sand roads, having to remove power lines or reinforcing the road after heavy rainfall in the desert. The greatest challenge is timing; the dragline needs to be operational as soon as possible. State-of-the-art equipment, coupled with knowledge and experience, ensures the heavy equipment reaches its destination safely and on time. Slashing travel time for through the desert, reducing travel excavation site of native American El Segundo Mine, USA time with 60%, from over 30 to 12 artifacts. Because of these width Peabody Energy needed to move days. The better restrictions the SPMT train was their 3500-ton dragline over a longer than preferable, and a distance of 22 miles (32 km) The dragline was the first machine option was special support structure was through the New Mexican desert of that weight to be transported designed to complete the job; we to their El Segundo Mine. over such a long distance. This job to load the added a steel structure made of required the removal of the bucket beams, each 3 ft tall, on top of The dragline, the size of a ship on and walking shoes in order to load dragline each trailer to function as load dry land, is designed to ‘walk’ by the dragline onto trailers for more spreader to ensure the load was using shoes that lift and advance feasible transport. -

Application for Declaration of the Mt Newman Railway, FMG Response To

FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LIMITED RESPONSE DATED 6 MAY 2005 IN RESPONSE TO THE ISSUES PAPER RELEASED BY THE NATIONAL COMPETITION COUNCIL DATED 11 MARCH 2005 2 RESPONSE BY FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LIMITED TO THE ISSUES PAPER RELEASED BY THE NATIONAL COMPETITION COUNCIL DATED 11 MARCH 2005 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Fortescue Metals Group Limited (“Fortescue”) refers to: (1) Fortescue’s Application under Part IIIA of the Trade Practices Act for Declaration of the service provided by BHP Billiton Iron Ore Pty Ltd dated 11 June 2004 (“Declaration Application”); (2) Fortescue’s Supplementary Submissions dated 8 July 2004 (“Supplementary Submissions”); and (3) Fortescue’s Submissions dated 4 October 2004 (“Preliminary Issues Paper Submissions”). 1.2 Fortescue also refers to the Issues Paper dated 11 March 2005 issued by the National Competition Council (“NCC”). In its Issues Paper, the NCC sought comments on what it considered to be the principal issues in considering Fortescue’s Declaration Application for declaration of the Service (described as the use of that part of the Mount Newman railway line specified in Fortescue’s Declaration Application). 1.3 Specifically, the NCC sought comments on the following questions: What is an appropriate duration for declaration of the Mount Newman Railway Service and why? Are there any reasonably foreseeable factors which may materially affect the NCC’s assessment of Fortescue’s Application for declaration? What is the time frame for the realization of such factors? 1.4 The NCC cannot recommend that a service be declared unless it believes all the criteria set out in section 44G(2) of the Trade Practices Act have been satisfied. -

Licence Environmental Protection Act 1986, Part V Licensee

Licence Environmental Protection Act 1986, Part V Licensee: Chichester Metals Pty Ltd Licence: L8454/2010/2 Registered office: 87 Adelaide Terrace EAST PERTH WA 6004 ACN: 109 264 262 Premises address: Christmas Creek Mine Site Tenements E46/610, E46/612, M46/320, M46/321, M46/322, M46/323, M46/324, M46/325, M46/326, M46/327, M46/328, M46/329, M46/330, M46/331, M46/332, M46/333, M46/334, M46/335, M46/336, M46/337, M46/338, M46/339, M46/340, M46/341, M46/342, M46/343, M46/344, M46/345, M46/346, M46/347, M46/348, M46/349, M46/350, M46/351, M46/352, M46/353, M46/354, M46/355, M46/403, M46/406, M46/412, M46/413, M46/414, M46/415, M46/416, M46/417, M46/418, M46/419, M46/420, M46/421, M46/422, M46/423, M46/424, G46/7, L46/49, L46/56, L46/58, L46/86, L46/87, L46/106, L46/111 E46/566 and L46/66 MULGA DOWNS WA 6751 As depicted in Schedule 1 Issue date: Thursday, 20 August 2015 Commencement date: Monday, 24 August 2015 Expiry date: Saturday, 23 August 2036 Prescribed premises category Schedule 1 of the Environmental Protection Regulations 1987 Category Approved premises Category Category description production or production or design number design capacity capacity 5 Processing or beneficiation of metallic 50,000 tonnes or 77,000,000 tonnes or non-metallic ore more per year per Annual Period 6 Mine dewatering 50,000 tonnes or 43,000,000 tonnes more per year per Annual Period (injected) 52 Electric power generation 10 MW or more in 56 MW aggregate (using a fuel other than natural gas) 54 Sewage facility 100 cubic metres 1,040 cubic metres or more per day per day 57 Used tyre storage 100 tyres or more 2,000 tyres Environmental Protection Act 1986 Page 1 of 34 Licence: L8454/2010/2 Amendment date: 14 July 2017 File Number: 2010/003105 IRLB_TI0672 v2.9 64 Class II putrescible landfill 20 tonnes or more 10,000 tonnes per per year Annual period 73 Bulk storage of chemicals 1,000 cubic metres 15,183.1 cubic in aggregate metres in aggregate Conditions This Licence is subject to the conditions set out in the attached pages.