Poems, Stories, Essays Debra K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index the Horn Book Magazine

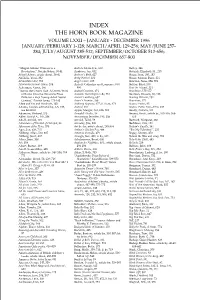

INDEX THE HORN BOOK MAGAZINE VOLUME LXXII – JANUARY - DECEMBER 1996 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1-128; MARCH/APRIL 129-256; MAY/JUNE 257- 384; JULY/AUGUST 385-512; SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 513-656; NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 657-800 “Abigail Adams: Witness to a Andrew McAndrew, 690 Batboy, 346 Revolution,” Natalie Bober, 38-41 Andrews, Jan, 632 Battrick, Elizabeth M., 239 Abigail Adams, article about, 38-41 Andrew’s Bath, 627 Bauer, Joan, 180, 183 Abolafia, Yossi, 332 Andy Warhol, 301 Bauer, Marion Dane, 221 Abracadabra Kid, 758 Angel’s Gate, 205 Bawden, Nina, 354; 591 Absolutely Normal Chaos, 204 Anholt, Catherine and Laurence, 689, Baylor, Byrd, 100 Ackerman, Karen, 186 690 Bear for Miguel, 331 “Across the Center Line: A Dozen Years Animal Crackers, 474 Beardance, 175-177 of Books from the Delacorte Press Animals That Ought to Be, 754 Bearden, Romare, 86; 185 Prize for a First Young-Adult Novel Anisett Lundberg, 637 Bearing Witness, 232 Contest,” Patrick Jones, 178-183 Annie’s Promise, 486 Bearstone, 175 Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me, 102 Anthony Reynoso, 477; il. from, 478 Beatrix Potter, 95 Adams, Lauren, editorial by, 4-5; 133; Antics!, 484 Beatrix Potter 1866–1943, 239 see Booklist Apple, Margot, 484; 626; 765 Beatty, Patricia, 101 Adamson, Richard, 573 Armadillo Rodeo, 59 Beavin, Kristi, article by, 105-109; 566- Adler, David A., 187, 236 Armstrong, Jennifer, 193, 236 573 Adoff, Arnold, 103 Arnold, Tedd, 59 Bechard, Margaret, 360 Adventures of Hershel of Ostropol, 83 Arnosky, Jim, 220 Beddows, Eric, 721 Afternoon of the Elves, 573 Art books, article about, 295-304 Beduin’s Gazelle, 341 Agee, Jon, 626; 715 Arthur’s Chicken Pox, 484 “Bee My Valentine!”, 235 Ahlberg, Allan, 590; 687 Artist in Overalls, 479 Begay, Shonto, 470 Ahlberg, Janet, 687 Aruego, Jose, 458; il. -

Subculture Magazine - Alternative Music and Culture Magazine

Subculture Magazine - alternative music and culture magazine. The ultimate ...c, darkwave, synthpop, alternative and post punk music. always on the edge. User Password Sign Up | Forgot Password Thursday, Dec 08 , 2005 Devo - Live 1980 (DVD) Posted :Thu, Dec 8th, 2005 00:20:24 Devo Devo - Live 1980 (DVD) Target Video Review By : Vivien Weimar With 80s nostalgia being de rigueur these days, the time is ripe for a DEVO reunion. The reclusive new wave band usually doesn't tour much as original founder Mark Mothersbaugh has since moved on to creating commercials and soundtracks at his Los Angeles production company Mutato Muzika (that fantastically weird space-ship-looking building on Sunset Boulevard) along with the other Devo members save Jerry Casale who has been directing videos for such bands as the Foo Fighters and Soundgarden. However, this summer Devo got together and played limited dates all across the country--and this fall they released Live 1980, a full-length concert video shot at the Phoenix Theatre in Petaluma, CA on August 17, 1980. Complete with white uniforms, blue background screen and "energy domes" (don't you dare call them flower-pot hats), Devo play the hits off of their albums, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We are Devo!, Duty Now For the Future and Freedom of Choice. Twenty-one songs are featured in this 75-minute disc including the classic MTV staple "Whip It", the oft-covered "Girl U Want", and their own covers of Johnny River's classic "Secret Agent Man" and the Rolling Stones "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction". -

FINAL Faith Essays

Townsend Press • 439 Kelley Drive • West Berlin, NJ 08091 Phone: (888) 752-6410 • Fax: (800) 225-8894 • Web: www.townsendpress.com Ten Sample "What I Believe" Essays 1. Good Deeds and Joy Tanya Savory 2 2. Believe It or Not Dawn Cogliser 5 3. How God Works George Mattmiller 9 4. This I Believe Tonya Lapido 15 5. My Personal Faith Ayesha Rahman 18 6. What I Believe John Langan 22 7. Numinosity Sara Walden Oremland 27 8. Opportunities to Give Back Bob Miedel 31 9. What I Believe Richard Kratz 35 10. What I Believe Sally Friedman 39 Copyright © 2019 by Townsend Press, Inc. 1 1 GOOD DEEDS AND JOY Tanya Savory When I was a child, my brother and I often stayed at our grandparents' tiny apartment in Pennsylvania for a week or so during the summers. Prior to our arrival, my grandmother did everything she could think of to make sure our stay would be perfect. She put candy in little containers everywhere and bought cheap comic books for us. She made a huge jar of bubble mixture out of dish soap and created "magic bubble wands" out of old hangers. As I grew older, I came to realize that my grandparents were poor, though I would never have guessed it back then. Every evening before bedtime, I'd sit out on the small front porch with my grandmother and blow soap bubbles. Sometimes the evening summer breeze would blow the bubbles back to us, and they would land on my cheek with a tiny pop. I'd screech with laughter and my grandmother would sometimes say, "That's a whisper from Jesus." "What's he whispering about?" I'd ask. -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

Fairy Tales & Legends: the Novels

Koertge, Ron. Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Dresses (Little Red Riding Hood) Levine, Gail Carson. Fairest (Snow White isn’t the fairest of them all) These are tales that are written in full Lo, Malinda. novel form, with intricately developed Ash (Cinderella) plots and characters. Sometimes the Marillier, Juliet. version is altered, such as taking place in a Wildwood Dancing (The Frog Prince different location or being told through and Twelve Dancing Princesses, set in the eyes of a different character. Transylvania) Anderson, Jodi Lynn. Martin, Rafe. Tiger Lily (Peter Pan) Birdwing (A continuation of Six Swans) Barron, T.A. Masson, Sophie. The Lost Years of Merlin series Serafin (Puss in Boots, only the cat is an Great Tree of Avalon series angel in disguise) Bunce, Elizabeth. McKinley, Robin. A Curse as Dark as Gold (Rumplestiltskin) Beauty (Beauty & the Beast) Coombs, Kate. Spindle’s End (Sleeping Beauty) The Runaway Princess Meyer, Marissa. (A new twist on old tales) Lunar Chronicles (Dystopian fairy tales) Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Meyer, Walter Dean. Arthur trilogy Amiri & Odette (Swan Lake set in the Projects) Delsol, Wendy. Stork trilogy (Snow Queen) Napoli, Donna Jo. Dokey, Cameron. Beast (Beauty & the Beast, set in Persia, Golden (Rapunzel) told from Beast’s point of view) Beauty Sleep (Sleeping Beauty) Breath (Pied Piper) Donoghue, Emma. Crazy Jack (Jack and the Beanstalk; Kissing the Witch (13 tales loosely Jack’s looking for his dad) connected to each other) The Magic Circle (Hansel & Gretel; the witch’s story) Durst, Sarah Beth. Ice (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Pearce, Jackson. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

What Buddhists Believe Expanded 4Th Edition

WhatWhat BuddhistBuddhist BelieveBelieve Expanded 4th Edition Dr. K. Sri Dhammanada HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Published by BUDDHIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY MALAYSIA 123, Jalan Berhala, 50470 Kuala Lumpur, 1st Edition 1964 Malaysia 2nd Edition 1973 Tel: (603) 2274 1889 / 1886 3rd Edition 1982 Fax: (603) 2273 3835 This Expanded Edition 2002 Email: [email protected] © 2002 K Sri Dhammananda All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any in- formation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover design and layout Sukhi Hotu ISBN 983-40071-2-7 What Buddhists Believe Expanded 4th Edition K Sri Dhammananda BUDDHIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY MALAYSIA This 4th edition of What Buddhists Believe is specially published in conjunction with Venerable Dr K Sri Dhammananda’s 50 Years of Dhammaduta Service in Malaysia and Singapore 1952-2002 (BE 2495-2545) Photo taken three months after his arrival in Malaysia from Sri Lanka, 1952. Contents Forewordxi Preface xiii 1 LIFE AND MESSAGE OF THE BUDDHA CHAPTER 1 Life and Nature of the Buddha Gautama, The Buddha 8 His Renunciation 24 Nature of the Buddha27 Was Buddha an Incarnation of God?32 The Buddha’s Service35 Historical Evidences of the Buddha38 Salvation Through Arahantahood41 Who is a Bodhisatva?43 Attainment of Buddhahood47 Trikaya — The Three Bodies of the Buddha49 -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

085765096700 Hd Movies / Game / Software / Operating System

085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Harap di isi dan kirim ke [email protected] Isi data : NAMA : ALAMAT : NO HP : HARDISK : TOTAL KESELURUHAN PENGISIAN HARDISK : Untuk pengisian hardisk: 1. Tinggal titipkan hardisk internal/eksternal kerumah saya dari jam 07:00-23:00 WIB untuk alamat akan saya sms.. 2. List pemesanannya di kirim ke email [email protected]/saat pengantar hardisknya jg boleh, bebas pilih yang ada di list.. 3. Pembayaran dilakukan saat penjemputan hardisk.. 4. Terima pengiriman hardisk, bagi yang mengirimkan hardisknya internal dan external harap memperhatikan packingnya.. Untuk pengisian beserta hardisknya: 1. Transfer rekening mandiri, setelah mendapat konfirmasi transfer, pesanan baru di proses.. 2. Hardisk yang telah di order tidak bisa di batalkan.. 3. Pengiriman menggunakan jasa Jne.. 4. No resi pengiriman akan di sms.. Lama pengerjaan 1 - 4 hari tergantung besarnya isian dan antrian tapi saya usahakan secepatnya.. Harga Pengisian Hardisk : Dibawah Hdd320 gb = 50.000 Hdd 500 gb = 70.000 Hdd 1 TB =100.000 Hdd 1,5 TB = 135.000 Hdd 2 TB = 170.000 Yang memakai hdd eksternal usb 2.0 kena biaya tambahan Check ongkos kirim http://www.jne.co.id/ BATAM GAME 085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Movies 0 GB Game Pc 0 GB Software 0 GB EbookS 0 GB Anime dan Concert 0 GB 3D / TV SERIES / HD DOKUMENTER 0 GB TOTAL KESELURUHAN 0 GB 1. -

61368/Sheet Music/9-36

10 Sheet Music Direct 11 Complete Alphabetical Sheet Listing 30 Wedding Sheet Music 30 Easy Piano Sheet Music 31 Piano Solo Sheet Music 33 Big-Note Piano Sheet Music 34 Five-Finger Sheet Music 34 Piano Duet Sheet Music 34 Vocal Sheet Music 35 Organ Sheet Music 35 Guitar Sheet Music 35 Accordion Sheet Music 35 Instrumental Sheet Music 10 SHEETSHEET MUSICMUSIC DIRECTDIRECT SHEET MUSIC The most popular site on the web for downloading top-quality, accurate, legal sheet music! Sheet Music Direct (www.SheetMusicDirect.com) features nearly 10,000 popular songs in a variety of musical and notation styles, ranging from piano/vocal to guitar tablature. More top songs are added to Sheet Music Direct daily and are searchable by title, artist, composer or format. With state-of-the-art Scorch® 2 technology from Sibelius®, sheet music files are quick to download, fun to interact with, and easy to use; visitors can see the music on screen, transpose the song to any key, and even listen to a MIDI file of the tune before you buy it! We have the strongest encryption commercially available so you can be assured that all transactions are completely safe. Hal Leonard offers excellent in-store and on-line affiliate programs: The In-Store Program allows you to sell your customers sheet music from a computer within your store. You can view the music, transpose to any key, test print it, and listen to it before the customer purchases it. The On-Line Affiliate Program allows you to place a link to SMD on your own website, and earn commissions on the sales that these click- These programs are available to any throughs generate. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2q169884 Author Hollander, Amanda Farrell Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Amanda Farrell Hollander 2015 © Copyright by Amanda Farrell Hollander 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 by Amanda Farrell Hollander Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Joseph E. Bristow, Chair “The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915” intervenes in current scholarship that addresses the impact of Fabian socialism on the arts during the fin de siècle. I argue that three particular Fabian writers—Evelyn Sharp, E. Nesbit, and Jean Webster—had an indelible impact on children’s literature, directing the genre toward less morally didactic and more politically engaged discourse. Previous studies of the Fabian Society have focused on George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb to the exclusion of women authors producing fiction for child readers. After the Fabian Society’s founding in 1884, English writers Sharp and Nesbit, and American author Webster published prolifically and, in their work, direct their socialism toward a critical and deliberate reform of ii literary genres, including the fairy tale, the detective story, the boarding school novel, adventure yarns, and epistolary fiction. -

Grim Tales Cassinaprojects.Com Curated by September 7 - October 21, 2017 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 7, 6-8 PM

For Immediate Release CASSINA PROJECTS 508 West 24th Street New York, NY, 10011 Grim Tales cassinaprojects.com Curated by September 7 - October 21, 2017 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 7, 6-8 PM Cassina Projects and ARTUNER are delighted to introduce Grim Tales, a new group show opening on September 7th, 2017 at Cassina Projects, New York City, featuring the works of Malte Bruns, Jamie Fitzpatrick, and Patrizio Di Massimo. Stories of bravery and horror, of villains, of misty full moons, of dark and mysterious rooms in ancient castles. No matter our age, the folktales collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 19th century never fail to enchant us. The power of these stories lies beyond their fantastic setting and awesome events: they are timeless and archetypal; they challenge our point of view and sense of morality. While an indispensable repository of folklore, because of their multi-layered and symbolic nature, these stories were historically perceived as subversive and potentially dangerous tools. Indeed they were, for they took their readers on a fantastical journey of darkness and discovery. It is only in contemporary works able to do the same that we can discover the skilled storytellers of our own modern times. Malte Bruns, Patrizio Di Massimo, and Jamie Fitzpatrick weave visual narratives of power, desire, and dread through their artworks, often evoking an uncannily mysterious, playful, and yet serious atmosphere. Akin to fairy tales, the artworks featured in this exhibition offer more than what is visible on the surface: they hold a revealing mirror up to contemporary society. These three artists share a penchant for the garish and provocative: through the use of bold colors and tantalizing aesthetics, their artworks portray disconcerting human stereotypes as well as chimeric monsters.