Confluențe 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

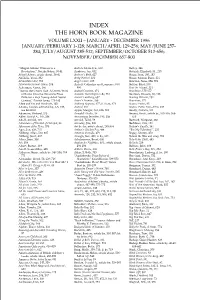

Index the Horn Book Magazine

INDEX THE HORN BOOK MAGAZINE VOLUME LXXII – JANUARY - DECEMBER 1996 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1-128; MARCH/APRIL 129-256; MAY/JUNE 257- 384; JULY/AUGUST 385-512; SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 513-656; NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 657-800 “Abigail Adams: Witness to a Andrew McAndrew, 690 Batboy, 346 Revolution,” Natalie Bober, 38-41 Andrews, Jan, 632 Battrick, Elizabeth M., 239 Abigail Adams, article about, 38-41 Andrew’s Bath, 627 Bauer, Joan, 180, 183 Abolafia, Yossi, 332 Andy Warhol, 301 Bauer, Marion Dane, 221 Abracadabra Kid, 758 Angel’s Gate, 205 Bawden, Nina, 354; 591 Absolutely Normal Chaos, 204 Anholt, Catherine and Laurence, 689, Baylor, Byrd, 100 Ackerman, Karen, 186 690 Bear for Miguel, 331 “Across the Center Line: A Dozen Years Animal Crackers, 474 Beardance, 175-177 of Books from the Delacorte Press Animals That Ought to Be, 754 Bearden, Romare, 86; 185 Prize for a First Young-Adult Novel Anisett Lundberg, 637 Bearing Witness, 232 Contest,” Patrick Jones, 178-183 Annie’s Promise, 486 Bearstone, 175 Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me, 102 Anthony Reynoso, 477; il. from, 478 Beatrix Potter, 95 Adams, Lauren, editorial by, 4-5; 133; Antics!, 484 Beatrix Potter 1866–1943, 239 see Booklist Apple, Margot, 484; 626; 765 Beatty, Patricia, 101 Adamson, Richard, 573 Armadillo Rodeo, 59 Beavin, Kristi, article by, 105-109; 566- Adler, David A., 187, 236 Armstrong, Jennifer, 193, 236 573 Adoff, Arnold, 103 Arnold, Tedd, 59 Bechard, Margaret, 360 Adventures of Hershel of Ostropol, 83 Arnosky, Jim, 220 Beddows, Eric, 721 Afternoon of the Elves, 573 Art books, article about, 295-304 Beduin’s Gazelle, 341 Agee, Jon, 626; 715 Arthur’s Chicken Pox, 484 “Bee My Valentine!”, 235 Ahlberg, Allan, 590; 687 Artist in Overalls, 479 Begay, Shonto, 470 Ahlberg, Janet, 687 Aruego, Jose, 458; il. -

Fairy Tales & Legends: the Novels

Koertge, Ron. Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Dresses (Little Red Riding Hood) Levine, Gail Carson. Fairest (Snow White isn’t the fairest of them all) These are tales that are written in full Lo, Malinda. novel form, with intricately developed Ash (Cinderella) plots and characters. Sometimes the Marillier, Juliet. version is altered, such as taking place in a Wildwood Dancing (The Frog Prince different location or being told through and Twelve Dancing Princesses, set in the eyes of a different character. Transylvania) Anderson, Jodi Lynn. Martin, Rafe. Tiger Lily (Peter Pan) Birdwing (A continuation of Six Swans) Barron, T.A. Masson, Sophie. The Lost Years of Merlin series Serafin (Puss in Boots, only the cat is an Great Tree of Avalon series angel in disguise) Bunce, Elizabeth. McKinley, Robin. A Curse as Dark as Gold (Rumplestiltskin) Beauty (Beauty & the Beast) Coombs, Kate. Spindle’s End (Sleeping Beauty) The Runaway Princess Meyer, Marissa. (A new twist on old tales) Lunar Chronicles (Dystopian fairy tales) Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Meyer, Walter Dean. Arthur trilogy Amiri & Odette (Swan Lake set in the Projects) Delsol, Wendy. Stork trilogy (Snow Queen) Napoli, Donna Jo. Dokey, Cameron. Beast (Beauty & the Beast, set in Persia, Golden (Rapunzel) told from Beast’s point of view) Beauty Sleep (Sleeping Beauty) Breath (Pied Piper) Donoghue, Emma. Crazy Jack (Jack and the Beanstalk; Kissing the Witch (13 tales loosely Jack’s looking for his dad) connected to each other) The Magic Circle (Hansel & Gretel; the witch’s story) Durst, Sarah Beth. Ice (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Pearce, Jackson. -

085765096700 Hd Movies / Game / Software / Operating System

085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Harap di isi dan kirim ke [email protected] Isi data : NAMA : ALAMAT : NO HP : HARDISK : TOTAL KESELURUHAN PENGISIAN HARDISK : Untuk pengisian hardisk: 1. Tinggal titipkan hardisk internal/eksternal kerumah saya dari jam 07:00-23:00 WIB untuk alamat akan saya sms.. 2. List pemesanannya di kirim ke email [email protected]/saat pengantar hardisknya jg boleh, bebas pilih yang ada di list.. 3. Pembayaran dilakukan saat penjemputan hardisk.. 4. Terima pengiriman hardisk, bagi yang mengirimkan hardisknya internal dan external harap memperhatikan packingnya.. Untuk pengisian beserta hardisknya: 1. Transfer rekening mandiri, setelah mendapat konfirmasi transfer, pesanan baru di proses.. 2. Hardisk yang telah di order tidak bisa di batalkan.. 3. Pengiriman menggunakan jasa Jne.. 4. No resi pengiriman akan di sms.. Lama pengerjaan 1 - 4 hari tergantung besarnya isian dan antrian tapi saya usahakan secepatnya.. Harga Pengisian Hardisk : Dibawah Hdd320 gb = 50.000 Hdd 500 gb = 70.000 Hdd 1 TB =100.000 Hdd 1,5 TB = 135.000 Hdd 2 TB = 170.000 Yang memakai hdd eksternal usb 2.0 kena biaya tambahan Check ongkos kirim http://www.jne.co.id/ BATAM GAME 085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Movies 0 GB Game Pc 0 GB Software 0 GB EbookS 0 GB Anime dan Concert 0 GB 3D / TV SERIES / HD DOKUMENTER 0 GB TOTAL KESELURUHAN 0 GB 1. -

THEMATIC UNITS and Ever-Growing Digital Library Listing GRADES 9–12 THEMATIC UNITS

THEMATIC UNITS and Ever-Growing Digital Library Listing GRADES 9–12 THEMATIC UNITS GRADE 9 AUTHOR GENRE StudySync®TV UNIT 1 | Divided We Fall: Why do we feel the need to belong? Writing Focus: Narrative Marigolds (SyncStart) Eugenia Collier Fiction The Necklace Guy de Maupassant Fiction Friday Night Lights H.G. Bissinger Informational Text Braving the Wilderness: The Quest for True Belonging and the Courage to Stand Alone Brene Brown Informational Text Why I Lied to Everyone in High School About Knowing Karate Jabeen Akhtar Informational Text St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves Karen Russell Fiction Sure You Can Ask Me a Personal Question Diane Burns Poetry Angela’s Ashes: A Memoir Frank McCourt Informational Text Welcome to America Sara Abou Rashed Poetry I Have a Dream Martin Luther King, Jr. Argumentative Text The Future in My Arms Edwidge Danticat Informational Text UNIT 2 | The Call to Adventure: What will you learn on your journey? Writing Focus: Informational Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening Robert Frost Poetry 12 (from ‘Gitanjali’) Rabindranath Tagore Poetry The Journey Mary Oliver Poetry Leon Bridges On Overcoming Childhood Isolation and Finding His Voice: ‘You Can’t Teach Soul’ Jeff Weiss Informational Text Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters Chesley Sullenberger Informational Text Bessie Coleman: Woman Who ‘dared to dream’ Made Aviation History U.S. Airforce Informational Text Volar Judith Ortiz Cofer Fiction Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail Cheryl Strayed Informational Text The Art -

Children's Books by Canonical Authors in the EFL Classroom

English Language Teaching; Vol. 13, No. 11; 2020 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Children's Books by Canonical Authors in the EFL Classroom Elena Ortells¹ ¹ Department of English Studies, Universitat Jaume I of Castelló, Castelló de la Plana, Spain Correspondence: Department of English Studies, Universitat Jaume I of Castelló. Avda Sos Baynat, s/n. 12071 Castelló de la Plana, Spain. Received: September 22, 2020 Accepted: October 21, 2020 Online Published: October 27, 2020 doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n11p100 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n11p100 Abstract Students’ imperfect grasp of the target language is cited by educators as one of the main tenets and conundrums against the use of real literature in the EFL classroom. However, previous reviews have proven that children and teenagers are likely to become interested in texts of their own choice and in line with their current concerns. Hence, since encouraging them to read for pleasure and providing them with motivating and level-appropriate materials are basic requirements for success, instructors should receive essential support on how to supply their students with literary texts suitable for both their language level and interests. My intention in this article is thus two-fold. On the one hand, I aim to provide several strategies to overcome the negative attitudes against the use of real literature in the EFL classroom, which are deeply rooted in the educational community, by equipping educators with a theoretical framework that allows them to critically select the most appropriate literary materials for their students. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2q169884 Author Hollander, Amanda Farrell Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Amanda Farrell Hollander 2015 © Copyright by Amanda Farrell Hollander 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 by Amanda Farrell Hollander Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Joseph E. Bristow, Chair “The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915” intervenes in current scholarship that addresses the impact of Fabian socialism on the arts during the fin de siècle. I argue that three particular Fabian writers—Evelyn Sharp, E. Nesbit, and Jean Webster—had an indelible impact on children’s literature, directing the genre toward less morally didactic and more politically engaged discourse. Previous studies of the Fabian Society have focused on George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb to the exclusion of women authors producing fiction for child readers. After the Fabian Society’s founding in 1884, English writers Sharp and Nesbit, and American author Webster published prolifically and, in their work, direct their socialism toward a critical and deliberate reform of ii literary genres, including the fairy tale, the detective story, the boarding school novel, adventure yarns, and epistolary fiction. -

Grim Tales Cassinaprojects.Com Curated by September 7 - October 21, 2017 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 7, 6-8 PM

For Immediate Release CASSINA PROJECTS 508 West 24th Street New York, NY, 10011 Grim Tales cassinaprojects.com Curated by September 7 - October 21, 2017 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 7, 6-8 PM Cassina Projects and ARTUNER are delighted to introduce Grim Tales, a new group show opening on September 7th, 2017 at Cassina Projects, New York City, featuring the works of Malte Bruns, Jamie Fitzpatrick, and Patrizio Di Massimo. Stories of bravery and horror, of villains, of misty full moons, of dark and mysterious rooms in ancient castles. No matter our age, the folktales collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 19th century never fail to enchant us. The power of these stories lies beyond their fantastic setting and awesome events: they are timeless and archetypal; they challenge our point of view and sense of morality. While an indispensable repository of folklore, because of their multi-layered and symbolic nature, these stories were historically perceived as subversive and potentially dangerous tools. Indeed they were, for they took their readers on a fantastical journey of darkness and discovery. It is only in contemporary works able to do the same that we can discover the skilled storytellers of our own modern times. Malte Bruns, Patrizio Di Massimo, and Jamie Fitzpatrick weave visual narratives of power, desire, and dread through their artworks, often evoking an uncannily mysterious, playful, and yet serious atmosphere. Akin to fairy tales, the artworks featured in this exhibition offer more than what is visible on the surface: they hold a revealing mirror up to contemporary society. These three artists share a penchant for the garish and provocative: through the use of bold colors and tantalizing aesthetics, their artworks portray disconcerting human stereotypes as well as chimeric monsters. -

A Comparative Study of the Use of Folktales in Nazi Germany and in Contemporary Fiction for Young Adults

SPINNING THE WHEEL: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE USE OF FOLKTALES IN NAZI GERMANY AND IN CONTEMPORARY FICTION FOR YOUNG ADULTS by Kallie George B.A., University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Children's Literature) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2007 © Kallie George, 2007 Abstract This thesis compares a selection of contemporary Holocaust novels for young adults that rework Grimm folklore to the Nazi regime's interpretation and propagandistic use of the same Grimm folklore. Using the methodology of intertextuality theory, in particular Julia Kristeva's concepts of monologic and dialogic discourse, this thesis examines the transformation of the Grimms' folktales "Hansel and Gretel," "Briar Rose," "Aschenputtel" and "Fitcher's Bird" in Louise Murphy's The True Story of Hansel and Gretel, Jane Yolen's Briar Rose and Peter Rushforth's Kindergarten. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract " Table of Contents iii Acknowledgements iv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Brothers Grimm 1 1.2 Folktales between the Era of the Brothers Grimm and the Nazi Era 9 1.3 Nazi Germany and the Use and Abuse of Folktales 12 1.4 Holocaust Literature for Children and Young Adults 15 1.5 Holocaust Novels by Louise Murphy, Jane Yolen and Peter Rushforth 23 1.6 Principal Research Questions 26 1.7 Methodology 28 2 Literature Review 31 2.1 Overview 31 2.2 Folklore Discourse and the Brothers Grimm : 31 2.3 Structuralism 33 2.4 Grimms' Retellings - Postmodernism -

Paper XVII. Unit 1 Nathaniel Hawthorne's the Scarlet Letter 1

Paper XVII. Unit 1 Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter 1. Introduction 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Biographical Sketch of Nathaniel Hawthorne 1.3 Major works of Hawthorne 1.4 Themes and outlines of Hawthorne’s novels 1.5 Styles and Techniques used by Hawthorne 2. Themes, Symbols and Structure of The Scarlet Letter 2.1 Detailed Storyline 2.2 Structure of The Scarlet Letter 2.3 Themes 2.3.1 Sin, Rejection and Redemption 2.3.2 Identity and Society. 2.3.3 The Nature of Evil. 2.4 Symbols 2.4.1 The letter A 2.4.2 The Meteor 2.4.3 Darkness and Light 3. Character List 3.1 Major characters 3.1.1 Hester Prynn 3.1.2 Roger Chillingworth 3.1.3 Arthur Dimmesdale 3.2 Minor Characters 3.2.1 Pearl 3.2.2 The unnamed Narrator 3.2.3 Mistress Hibbins 3.2.4 Governor Bellingham 4. Hawthorne’s contribution to American Literature 5. Questions 6. Further Readings of Hawthorne 1. Introduction 1.1 Objectives This Unit provides a biographical sketch of Nathaniel Hawthorne first. Then a list of his major works, their themes and outlines. It also includes a detailed discussion about the styles and techniques used by him. The themes, symbols and the structure of The Scarlet Letter are discussed next, followed by the list of major as well as minor characters. This unit concludes with a discussion about Hawthorne’s contribution to American literature and a set of questions. Lastly there is a list of further readings of Hawthorne to gain knowledge about the critical aspects of the novel. -

Download My Platonic Sweetheart, Mark Twain, Aeon Publishing

My Platonic Sweetheart, Mark Twain, Aeon Publishing Company, 1999, 1893766004, 9781893766006, . DOWNLOAD HERE The Avengers Nights of Wundagore, , Nov 1, 2000, , 160 pages. When Quicksilver and his sister, Scarlet Witch, are mysteriously drawn to Wundagore Mountain, they find themselves fighting off a mystical force that threatens to ruin nature .... Trauma and the Therapist Countertransference and Vicarious Traumatization in Psychotherapy With Incest Survivors, Laurie Anne Pearlman, Karen W. Saakvitne, 1995, , 451 pages. The focus of this book is the therapist who works with adult survivors of childhood incest and sexual abuse. The book reflects two important aspects of trauma and the therapist .... Advice to Little Girls , Mark Twain, Apr 16, 2013, , 24 pages. Brilliantly illustrated, this witty, charming story is perfect for clever girls, adults and the mischievous boys in their midst.. The Spelling Bee , Catherine Nichols, Mark Twain, 2007, Juvenile Fiction, 32 pages. A brief, simplified retelling of the episode in "Tom Sawyer" in which Tom cheats during the spelling bee, but later realizes he must make things right.. The Batman Going Batty, Jack Oliver, Rick Burchett, Feb 1, 2005, , 24 pages. Batman must find a way to foil Joker's plot to gas all of Gotham City using a hot air balloon.. A Double Barrelled Detective Story Easyread Super Large 24pt Edition, Mark Twain, Nov 28, 2008, Fiction, 192 pages. Books for All Kinds of Readers. ReadHowYouWant offers the widest selection of on-demand, accessible format editions on the market today. Each edition has been optimized for .... Pudd'nhead Wilson , Mark Twain, Sep 1, 2000, , 237 pages. Tells the story of two boys, one a slave and one his master, who are exchanged as infants, a secret that is not discovered until one becomes involved in a murder trial. -

The Best Short Stories of Mark Twain Free

FREE THE BEST SHORT STORIES OF MARK TWAIN PDF Mark Twain | 384 pages | 30 Aug 2011 | Random House USA Inc | 9780812971187 | English | New York, United States The Best Short Stories of Mark Twain by Mark Twain, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Smiley, as you requested me to do, and I hereunto append the result. If you can get any information out of it you are cordially welcome to it. I have a lurking suspicion that your Leonidas W. Smiley is a myth-that you never knew such a personage, and that you only conjectured that if I asked old Wheeler about him it would remind him of his infamous Jim Smiley, and he would go to work and bore me nearly to death with some infernal reminiscence of him as long and tedious as it should be useless to me. If that was your design, Mr. Ward, it will gratify you to know that it succeeded. I found Simon Wheeler dozing comfortably by the bar-room The Best Short Stories of Mark Twain of the little old dilapidated tavern in the ancient mining camp of Boomerang, and I noticed that he was fat and bald-headed, and had an expression of winning gentleness and simplicity upon his tranquil countenance. -

The Boy Who Became a Hedgehog

Curiosity Season 2015 / 2016 curiosity property, characteristic of a curious person: she is known for her curiosity; no one likes him because of his curiosity / expr. to be consumed with curiosity // the desire to know, to learn things that are not essential to know: he felt a pang of curiosity; this piques your curiosity; his curiosity made him do it / his eyes are gleaming from curiosity / derog. old woman's curiosity; explorative curiosity ∙ expr. giving full rein to one's curiosity dwelling somewhere and curiously watching something; curious adj., someone who wants to know, to learn things that are not essential to know: curious child; don't be so curious Contents Click 6 Behind the Wall 8 Puppet Theatre Maribor 10 Minorites 12 Repertoire 14 Premieres 16 Repetitions 24 1,5−3 3+ 5+ 6+ 12+ 15+ Proof of Excellence 51 Our Puppetry Festivals 52 Summer Puppet Pier 54 Biennial of Puppetry Artists of Slovenia 56 Complementary Programs 58 Minoritska Cafe 60 Art Education Activities 64 Studio LGM 68 A Hearty Welcome 70 Box Office 72 Season Tickets and Discounts 73 Who is Who 80 5 Through the thousands of years of the history Here at Puppet Theatre Maribor, we try our of humanity, our thinkers, prophets, artists and best to establish the right conditions for scholars, seekers of the natural order and truth, fostering a healthy and vigorous curiosity. It Click have succeeded in setting up and preserving the is our hope that this curiosity may stimulate values on which rests our modern civilization. the development of important skills and pose These foundations are steadfast – for if they questions on all kinds of things, set in the weren't, and in the face of the irresponsible framework of original puppetry aesthetics.