UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

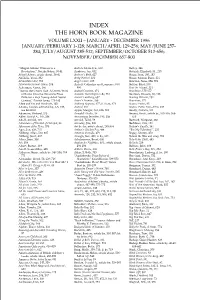

Index the Horn Book Magazine

INDEX THE HORN BOOK MAGAZINE VOLUME LXXII – JANUARY - DECEMBER 1996 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1-128; MARCH/APRIL 129-256; MAY/JUNE 257- 384; JULY/AUGUST 385-512; SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 513-656; NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 657-800 “Abigail Adams: Witness to a Andrew McAndrew, 690 Batboy, 346 Revolution,” Natalie Bober, 38-41 Andrews, Jan, 632 Battrick, Elizabeth M., 239 Abigail Adams, article about, 38-41 Andrew’s Bath, 627 Bauer, Joan, 180, 183 Abolafia, Yossi, 332 Andy Warhol, 301 Bauer, Marion Dane, 221 Abracadabra Kid, 758 Angel’s Gate, 205 Bawden, Nina, 354; 591 Absolutely Normal Chaos, 204 Anholt, Catherine and Laurence, 689, Baylor, Byrd, 100 Ackerman, Karen, 186 690 Bear for Miguel, 331 “Across the Center Line: A Dozen Years Animal Crackers, 474 Beardance, 175-177 of Books from the Delacorte Press Animals That Ought to Be, 754 Bearden, Romare, 86; 185 Prize for a First Young-Adult Novel Anisett Lundberg, 637 Bearing Witness, 232 Contest,” Patrick Jones, 178-183 Annie’s Promise, 486 Bearstone, 175 Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me, 102 Anthony Reynoso, 477; il. from, 478 Beatrix Potter, 95 Adams, Lauren, editorial by, 4-5; 133; Antics!, 484 Beatrix Potter 1866–1943, 239 see Booklist Apple, Margot, 484; 626; 765 Beatty, Patricia, 101 Adamson, Richard, 573 Armadillo Rodeo, 59 Beavin, Kristi, article by, 105-109; 566- Adler, David A., 187, 236 Armstrong, Jennifer, 193, 236 573 Adoff, Arnold, 103 Arnold, Tedd, 59 Bechard, Margaret, 360 Adventures of Hershel of Ostropol, 83 Arnosky, Jim, 220 Beddows, Eric, 721 Afternoon of the Elves, 573 Art books, article about, 295-304 Beduin’s Gazelle, 341 Agee, Jon, 626; 715 Arthur’s Chicken Pox, 484 “Bee My Valentine!”, 235 Ahlberg, Allan, 590; 687 Artist in Overalls, 479 Begay, Shonto, 470 Ahlberg, Janet, 687 Aruego, Jose, 458; il. -

The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce

m ill iiiii;!: t!;:!iiii; PS Al V-ID BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henrg W, Sage 1891 B^^WiS _ i.i|j(i5 Cornell University Library PS 1097.A1 1909 V.10 The collected works of Ambrose Blerce. 3 1924 021 998 889 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021998889 THE COLLECTED WORKS OF AMBROSE BIERCE VOLUME X UIBI f\^^°\\\i COPYHIGHT, 1911, Br THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY CONTENTS PAGE THE OPINIONATOR The Novel 17 On Literary Criticism 25 Stage Illusion 49 The Matter of Manner 57 On Reading New Books 65 Alphab£tes and Border Ruffians .... 69 To Train a Writer 75 As to Cartooning 79 The S. p. W 87 Portraits of Elderly Authors .... 95 Wit and Humor 98 Word Changes and Slang . ... 103 The Ravages of Shakspearitis .... 109 England's Laureate 113 Hall Caine on Hall Gaining . • "7 Visions of the Night . .... 132 THE REVIEWER Edwin Markham's Poems 137 "The Kreutzer Sonata" .... 149 Emma Frances Dawson 166 Marie Bashkirtseff 172 A Poet and His Poem 177 THE CONTROVERSIALIST An Insurrection of the Peasantry . 189 CONTENTS page Montagues and Capulets 209 A Dead Lion . 212 The Short Story 234 Who are Great? 249 Poetry and Verse 256 Thought and Feeling 274 THE' TIMOROUS REPORTER The Passing of Satire 2S1 Some Disadvantages of Genius 285 Our Sacrosanct Orthography . 299 The Author as an Opportunity 306 On Posthumous Renown . -

Romantic Textualities, 22

R OMANTICT EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1780–1840 • ISSN 1748-0116 ◆ ISSUE 22 ◆ SPRING 2017 ◆ SPECIAL ISSUE : FOUR NATIONS FICTION BY WOMEN, 1789–1830 ◆ www.romtext.org.uk ◆ CARDIFF UNIVERSITY PRESS ◆ Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 22 (Spring 2017) Available online at <www.romtext.org.uk/>; archive of record at <https://publications.cardiffuniversitypress.org/index.php/RomText>. Journal DOI: 10.18573/issn.1748-0116 ◆ Issue DOI: 10.18573/n.2017.10148 Romantic Textualities is an open access journal, which means that all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. Unless otherwise noted, the material contained in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (cc by-nc-nd) Interna- tional License. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ for more information. Origi- nal copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. C b n d Romantic Textualities is an imprint of Cardiff University Press, an innovative open-access publisher of academic research, where ‘open-access’ means free for both readers and writers. Find out more about the press at cardiffuniversitypress.org. Editors: Anthony Mandal, Cardiff University Maximiliaan -

BA THESIS Alex Lorenzů

Charles University in Prague Faculty of Arts Department of Anglophone Literatures and Cultures BA THESIS Alex Lorenzů Literary, Cultural and Historical Influences in the Works and Beliefs of Oscar Wilde Literární, kulturní a historické vlivy v díle a přesvědčeních Oscara Wildea Prague 2012 Supervisor: PhDr. Zdeněk Beran Acknowledgements I would like to thank PhDr. Zdeněk Beran for his thorough consultation of the ideas behind my thesis and the approaches to them, as well as for his support during the writing process. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného či stejného titulu. V Praze dne 15. 8. 2012 …....................................... Alex Lorenzů Souhlasím se zapůjčením bakalářské práce ke studijním účelům. Abstract The thesis deals with the cultural and literary influences that can be traced in the works of Oscar Wilde. Its aim is to map out and elucidate some of the important motifs of the author's work and aesthetics in their own context as well as in the wider cultural-historical one. The methods used will be comparison of relevant materials, analysis of certain expressions typical of the author with their connotations, explaining the intertextual allusions in Wilde's work, and historical sources. The requisite attention will also be paid to Wilde as a representative of a subversive element of Victorian society and how this relates to his sexuality; that is to say, exploring the issue of the tabooing of non-heterosexuality, which may have been a decisive factor in Wilde's criticism of the conventions of his era and to his search of positive role-models in the ancient tradition both for his art and for his personal philosophy. -

Anacortes Museum Research Files

Last Revision: 10/02/2019 1 Anacortes Museum Research Files Key to Research Categories Category . Codes* Agriculture Ag Animals (See Fn Fauna) Arts, Crafts, Music (Monuments, Murals, Paintings, ACM Needlework, etc.) Artifacts/Archeology (Historic Things) Ar Boats (See Transportation - Boats TB) Boat Building (See Business/Industry-Boat Building BIB) Buildings: Historic (Businesses, Institutions, Properties, etc.) BH Buildings: Historic Homes BHH Buildings: Post 1950 (Recommend adding to BHH) BPH Buildings: 1950-Present BP Buildings: Structures (Bridges, Highways, etc.) BS Buildings, Structures: Skagit Valley BSV Businesses Industry (Fidalgo and Guemes Island Area) Anacortes area, general BI Boat building/repair BIB Canneries/codfish curing, seafood processors BIC Fishing industry, fishing BIF Logging industry BIL Mills BIM Businesses Industry (Skagit Valley) BIS Calendars Cl Census/Population/Demographics Cn Communication Cm Documents (Records, notes, files, forms, papers, lists) Dc Education Ed Engines En Entertainment (See: Ev Events, SR Sports, Recreation) Environment Env Events Ev Exhibits (Events, Displays: Anacortes Museum) Ex Fauna Fn Amphibians FnA Birds FnB Crustaceans FnC Echinoderms FnE Fish (Scaled) FnF Insects, Arachnids, Worms FnI Mammals FnM Mollusks FnMlk Various FnV Flora Fl INTERIM VERSION - PENDING COMPLETION OF PN, PS, AND PFG SUBJECT FILE REVIEW Last Revision: 10/02/2019 2 Category . Codes* Genealogy Gn Geology/Paleontology Glg Government/Public services Gv Health Hl Home Making Hm Legal (Decisions/Laws/Lawsuits) Lgl -

PDF of the Princess Bride

THE PRINCESS BRIDE S. Morgenstern's Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure The 'good parts' version abridged by WILLIAM GOLDMAN one two three four five six seven eight map For Hiram Haydn THE PRINCESS BRIDE This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it. How is such a thing possible? I'll do my best to explain. As a child, I had simply no interest in books. I hated reading, I was very bad at it, and besides, how could you take the time to read when there were games that shrieked for playing? Basketball, baseball, marbles—I could never get enough. I wasn't even good at them, but give me a football and an empty playground and I could invent last-second triumphs that would bring tears to your eyes. School was torture. Miss Roginski, who was my teacher for the third through fifth grades, would have meeting after meeting with my mother. "I don't feel Billy is perhaps extending himself quite as much as he might." Or, "When we test him, Billy does really exceptionally well, considering his class standing." Or, most often, "I don't know, Mrs. Goldman; what are we going to do about Billy?" What are we going to do about Billy? That was the phrase that haunted me those first ten years. I pretended not to care, but secretly I was petrified. Everyone and everything was passing me by. I had no real friends, no single person who shared an equal interest in all games. -

The Century Guild Hobby Horse Mitchell, Rebecca

The Century Guild Hobby Horse Mitchell, Rebecca DOI: 10.1086/696259 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Mitchell, R 2018, 'The Century Guild Hobby Horse' Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 112, no. 1, pp. 75-104. https://doi.org/10.1086/696259 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Version accepted for publication by Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America on 11/09/2015. Final version of record available at: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/696259 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

The Fabians Could Only Have Happened in Britain....In a Thoroughly Admirable Study the Mackenzies Have Captured the Vitality of the Early Years

THE famous circle of enthusiasts, reformers, brilliant eccentrics-Sha\y the Webbs, Wells-whose ideas and unconventional attitudes fashioned our modern world by Norman C&Jeanne MacKenzie AUTHORS OF H.G. Wells: A Biography PRAISE FOR Not quite a political party, not quite a pressure group, not quite a debating society, the Fabians could only have happened in Britain....In a thoroughly admirable study the MacKenzies have captured the vitality of the early years. Since much of this is anecdotal, it is immensely fun to read. Most im¬ portant, they have pinpointed (with¬ out belaboring) all the internal para¬ doxes of F abianism. —The Kirkus Reviews H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Bertrand Russell, part of the outstandingly talented and paradoxical group that led the way to socialist Britain, are brought into brilliant human focus in this marvelously detailed and anecdote-filled por¬ trait of the original members of the Fabian Society—with a fresh assessment of their contributions to social thought. “The first Fabians,” said Shaw, were “missionaries among the savages,” who laid the ground¬ work for the Labour Party, and whose mis¬ sionary zeal and passionate enthusiasms carried them from obscurity to fame. This voluble and volatile band of middle-class in¬ tellectuals grew up in a period of liberating ideas and changing morals, influenced by (continued on back flap) c A / c~ 335*1 MacKenzie* Norman Ian* Ml99f The Fabians / Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie* - New York : Simon and Schuster, cl977* — 446 p** [8] leaves of plates : ill* - ; 24 cm* Includes bibliographical references and index* ISBN 0—671—22347—X : $11.95 1* Fabian Society, London* I* Title. -

Fairy Tales & Legends: the Novels

Koertge, Ron. Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Dresses (Little Red Riding Hood) Levine, Gail Carson. Fairest (Snow White isn’t the fairest of them all) These are tales that are written in full Lo, Malinda. novel form, with intricately developed Ash (Cinderella) plots and characters. Sometimes the Marillier, Juliet. version is altered, such as taking place in a Wildwood Dancing (The Frog Prince different location or being told through and Twelve Dancing Princesses, set in the eyes of a different character. Transylvania) Anderson, Jodi Lynn. Martin, Rafe. Tiger Lily (Peter Pan) Birdwing (A continuation of Six Swans) Barron, T.A. Masson, Sophie. The Lost Years of Merlin series Serafin (Puss in Boots, only the cat is an Great Tree of Avalon series angel in disguise) Bunce, Elizabeth. McKinley, Robin. A Curse as Dark as Gold (Rumplestiltskin) Beauty (Beauty & the Beast) Coombs, Kate. Spindle’s End (Sleeping Beauty) The Runaway Princess Meyer, Marissa. (A new twist on old tales) Lunar Chronicles (Dystopian fairy tales) Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Meyer, Walter Dean. Arthur trilogy Amiri & Odette (Swan Lake set in the Projects) Delsol, Wendy. Stork trilogy (Snow Queen) Napoli, Donna Jo. Dokey, Cameron. Beast (Beauty & the Beast, set in Persia, Golden (Rapunzel) told from Beast’s point of view) Beauty Sleep (Sleeping Beauty) Breath (Pied Piper) Donoghue, Emma. Crazy Jack (Jack and the Beanstalk; Kissing the Witch (13 tales loosely Jack’s looking for his dad) connected to each other) The Magic Circle (Hansel & Gretel; the witch’s story) Durst, Sarah Beth. Ice (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Pearce, Jackson. -

The Picture of Dorian Gray Symbols and Motifs Worksheet

The Picture of Dorian Gray Symbols and Motifs Worksheet SYMBOL – A literal object, person, place etc. that represents a figurative idea/concept/emotion. MOTIF – a recurring image or concept that reiterates an idea/concept/emotion. Read the information about each element (supplied below) and summarise the important points (and add your own) to fill in this table. Symbol/Motif What it Significance to our represents understanding of the novel E.g. The painting Beauty, vanity, The presence of the painting is a the passing of time constant reminder of the true result and conscience. of Dorian’s actions. It allows him to act without thought of the consequences and to only worry about his own pleasure, but he cannot hide from it forever. Eventually the painting’s mere existence comes to torture Dorian. Flowers The book The opium dens James Vane Red and white SOURCE 1: Course Hero The Painting By far the most important symbol in the novel is Basil's portrait of Dorian. The centrepiece of the plot, the portrait interacts with Dorian throughout the narrative. When Dorian does something immoral, the results show up on the painting, while Dorian's own face stays unmarked and beautiful. This painting is Basil's best work, but must, because of its magical power, remain unseen by everyone except Dorian. Basil and Henry saw the portrait when it was first complete. Though it is rarely seen, this picture looms symbolically and metaphorically over the entire book. The picture takes the Victorian ideal of art to its logical extreme. If art is useful because it teaches a moral lesson, how perfect must this painting be since it is an immediate barometer of ethical changes? Basil's final glimpse of his masterpiece occurs when he says that to know Dorian he must see his soul. -

"Weapon of Starvation": the Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2015 A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919 Alyssa Cundy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cundy, Alyssa, "A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1763. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1763 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “WEAPON OF STARVATION”: THE POLITICS, PROPAGANDA, AND MORALITY OF BRITAIN’S HUNGER BLOCKADE OF GERMANY, 1914-1919 By Alyssa Nicole Cundy Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Western Ontario, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Western Ontario, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University 2015 Alyssa N. Cundy © 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the British naval blockade imposed on Imperial Germany between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles in July 1919. The blockade has received modest attention in the historiography of the First World War, despite the assertion in the British official history that extreme privation and hunger resulted in more than 750,000 German civilian deaths. -

085765096700 Hd Movies / Game / Software / Operating System

085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Harap di isi dan kirim ke [email protected] Isi data : NAMA : ALAMAT : NO HP : HARDISK : TOTAL KESELURUHAN PENGISIAN HARDISK : Untuk pengisian hardisk: 1. Tinggal titipkan hardisk internal/eksternal kerumah saya dari jam 07:00-23:00 WIB untuk alamat akan saya sms.. 2. List pemesanannya di kirim ke email [email protected]/saat pengantar hardisknya jg boleh, bebas pilih yang ada di list.. 3. Pembayaran dilakukan saat penjemputan hardisk.. 4. Terima pengiriman hardisk, bagi yang mengirimkan hardisknya internal dan external harap memperhatikan packingnya.. Untuk pengisian beserta hardisknya: 1. Transfer rekening mandiri, setelah mendapat konfirmasi transfer, pesanan baru di proses.. 2. Hardisk yang telah di order tidak bisa di batalkan.. 3. Pengiriman menggunakan jasa Jne.. 4. No resi pengiriman akan di sms.. Lama pengerjaan 1 - 4 hari tergantung besarnya isian dan antrian tapi saya usahakan secepatnya.. Harga Pengisian Hardisk : Dibawah Hdd320 gb = 50.000 Hdd 500 gb = 70.000 Hdd 1 TB =100.000 Hdd 1,5 TB = 135.000 Hdd 2 TB = 170.000 Yang memakai hdd eksternal usb 2.0 kena biaya tambahan Check ongkos kirim http://www.jne.co.id/ BATAM GAME 085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Movies 0 GB Game Pc 0 GB Software 0 GB EbookS 0 GB Anime dan Concert 0 GB 3D / TV SERIES / HD DOKUMENTER 0 GB TOTAL KESELURUHAN 0 GB 1.