Investigating Ethnographies About Modekngei a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

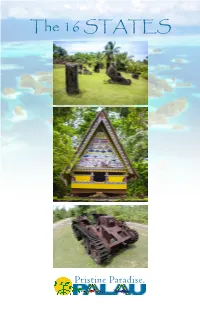

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Nakatani V. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) NORIYOSHI NAKATANI and NAKATANI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Respondents

Nakatani v. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) NORIYOSHI NAKATANI and NAKATANI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Respondents, v. MASAO NISHIZONO and SEIBU DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, Appellants, and REPUBLIC OF PALAU, Additional Appellant, and PACIFICA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, a Palau Corporation. MASAO NISHIZONO, aka KWON BOO SIK CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, Appellant, v. ROMAN TMETUCHL, MELWERT TMETUCHL, and NORIYOSHI NAKATANI, Respondents, and ⊥8 REPUBLIC OF PALAU, Additional Appellant, and PACIFICA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION a Palau Corporation, Respondent. CIVIL APPEAL NO. 5-86 Civil Action No. 25-85 and Civil Action No. 73-85 (consolidated) Supreme Court, Appellate Division Republic of Palau Opinion Decided: January 8, 1990 Nakatani v. Nishizono, 2 ROP Intrm. 7 (1990) Counsel for Appellants Masao Nishizono and Seibu Development Corporation: James S. Brooks Counsel for Respondents Noriyoshi Nakatani and Nakatani Company: John S. Tarkong Counsel for Appellant Republic of Palau: Richard Brungard, Acting Attorney General. Counsel for Appellee Pacifica Development Corp. and Melwert Tmetuchl and Respondents Roman Tmetuchl and Airai State Gov’t.: Johnson Toribiong BEFORE: ALEX R. MUNSON,1 Associate Justice; ROBERT A. HEFNER,2 Associate Justice; FREDERICK J. O’BRIEN, Associate Justice Pro Tem. ⊥9 PER CURIAM: As will be seen, the issues presented for this appeal are limited in scope and therefore an extensive dissertation as to the factual and procedural history for this protracted litigation is unnecessary. Only the background necessary for the resolution of the issues raised for this appellate panel need be set forth in any detail. BACKGROUND Civil Action No. 73-85 was commenced on May 9, 1985, when plaintiffs Noriyoshi Nakatani and Nakatani Construction Co. (Nakatani) filed their complaint against Masao Nishizono, AKA Kwon Boo Sik (Nishizono), Seibu Development Corporation, Seibu Sohgo Kaihatsu, Hisayuki Kojima, Airai State, and Roman Tmetuchl, individually and as Governor of Airai State. -

Personnel - Johnston, Edward (2)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 39, folder “Personnel - Johnston, Edward (2)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 39 of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMIN I STRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 01510 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL . Donor restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL Letter(s) CREATOR'S NAME . Thorpe, Richard RECEIVER'S NAME .... President DESCRIPTION . Trust Territory CREATION DATE 09/ 06/ 1974 COLLECTION/ SERIES/FOLDER ID 001900428 COLLECTION TITLE . Philip W. Buchen Files BOX NUMBER . 39 FOLDER TITLE . Personnel - Johnston, Edward ( 1)-(2) DATE WITHDRAWN . 08/ 26 / 1988 WITHDRAWING ARCHIVIST . LET NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 01511 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL . Donor restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL Notes CREATOR'S NAME . Daughtrey, Eva DESCRIPTION Note for the file concerning Robert Thorpe phone calls . CREATION DATE . 06/24/1976 COLLECTION/SERIES/FOLDER ID . -

Germany and Japan As Regional Actors in the Post-Cold War Era: a Role Theoretical Comparison

Alexandra Sakaki Germany and Japan as Regional Actors in the Post-Cold War Era: A Role Theoretical Comparison Trier 2011 GERMANY AND JAPAN AS REGIONAL ACTORS IN THE POST-COLD WAR ERA: A ROLE THEORETICAL COMPARISON A dissertation submitted by Alexandra Sakaki to the Political Science Deparment of the University of Trier in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission of dissertation: August 6, 2010 First examiner: Prof. Dr. Hanns W. Maull (Universität Trier) Second examiner: Prof. Dr. Christopher W. Hughes (University of Warwick) Date of viva: April 11, 2011 ABSTRACT Germany and Japan as Regional Actors in the Post-Cold War Era: A Role Theoretical Comparison Recent non-comparative studies diverge in their assessments of the extent to which German and Japanese post-Cold War foreign policies are characterized by continuity or change. While the majority of analyses on Germany find overall continuity in policies and guiding principles, prominent works on Japan see the country undergoing drastic and fundamental change. Using an explicitly comparative framework for analysis based on a role theoretical approach, this study reevaluates the question of change and continuity in the two countries‘ regional foreign policies, focusing on the time period from 1990 to 2010. Through a qualitative content analysis of key foreign policy speeches, this dissertation traces and compares German and Japanese national role conceptions (NRCs) by identifying policymakers‘ perceived duties and responsibilities of their country in international politics. Furthermore, it investigates actual foreign policy behavior in two case studies about German and Japanese policies on missile defense and on textbook disputes. -

Dr. Roy Murphy

US THE WHO, WHAT & WHY OF MANKIND Dr. Roy Murphy Visit us online at arbium.com An Arbium Publishing Production Copyright © Dr. Roy Murphy 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover design created by Mike Peers Visit online at www.mikepeers.com First Edition – 2013 ISBN 978-0-9576845-0-8 eBook-Kindle ISBN 978-0-9576845-1-5 eBook-PDF Arbium Publishing The Coach House 7, The Manor Moreton Pinkney Northamptonshire NN11 3SJ United Kingdom Printed in the United Kingdom Vi Veri Veniversum Vivus Vici 863233150197864103023970580457627352658564321742494688920065350330360792390 084562153948658394270318956511426943949625100165706930700026073039838763165 193428338475410825583245389904994680203886845971940464531120110441936803512 987300644220801089521452145214347132059788963572089764615613235162105152978 885954490531552216832233086386968913700056669227507586411556656820982860701 449731015636154727292658469929507863512149404380292309794896331535736318924 980645663415740757239409987619164078746336039968042012469535859306751299283 295593697506027137110435364870426383781188694654021774469052574773074190283 -

Jay Fox: the Life and Times of an American Radical

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2016 Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical David J. Collins Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Collins, David J., "Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical" (2016). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 338. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAY FOX: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN AMERICAN RADICAL A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By David J. Collins Spring 2016 ii iii iv Acknowledgements First, I have to acknowledge Ross K. Rieder who generously made his collection of Jay Fox papers available to me, as well as permission to use it for this project. Next, a huge thanks to Dr. Joseph U. Lenti who provided guidance and suggestions for improving the project, and put in countless hours editing and advising me on revisions. Dr. Robert Dean provided a solid knowledge of the time period through coursework and helped push this thesis forward. Dr. Mimi Marinucci not only volunteered her time to participate on the committee, but also provided support and guidance to me from my first year as an undergraduate at Eastern Washington University, and continues to be an influential mentor today. -

Roman Tmetuchl Family Trust V. Whipps, 8 ROP Intrm

Roman Tmetuchl Family Trust v. Whipps, 8 ROP Intrm. 317 (2001) ROMAN TMETUCHL FAMILY TRUST, Appellant, v. SURANGEL WHIPPS, Appellee. CIVIL APPEAL NO. 00-01 Civil Action No. 98-104 Argued: March 5, 2001 Decided: May 28, 2001 Counsel for Appellant: Johnson Toribiong Counsel for Appellee: John Rechucher BEFORE: ARTHUR NGIRAKLSONG, Chief Justice; LARRY W. MILLER, Associate Justice; KATHLEEN M. SALII, Associate Justice. MILLER, Justice: The Trial Division determined that a portion of land in an area known as Ngersung in Ngerusar Hamlet, Airai State, Lot No. 179, would belong to Appellee Surangel Whipps if he or the children of Ngirmekur Ksau tendered a sum of $998 to the Roman Tmetuchl Family Trust (the “Trust”). The money was tendered, and the Trust filed this appeal. Although we reject most of the Trust’s arguments, we conclude that a remand is necessary before we may resolve one of the issues it raises. In 1969, Ngirmekur Ksau, also known as Ngirmekur Tuchermel, was adjudged the owner of Ngersung. See Adelbai v. Tuchermel, 4 TTR 410 (1969). In 1970, Tmetuchl loaned Ksau $998, and Ksau ⊥318 executed a deed transferring a portion 1 of Ngersung to Roman Tmetuchl for the price of $998. The third paragraph of that deed states: To have and to hold these granted premises in fee simple, together with all the rights, easements and appurtenances thereto to the said Mr. Roman Tmetuchl of Koror, Palau District, Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, his successors and assigns forever, that also it was agreed in good will that some day if Ngirmekur Tuchermel’s children be able to repay Mr. -

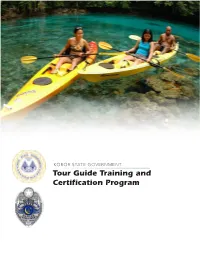

Tour Guide Manual)

KOROR STATE GOVERNMENT Tour Guide Training and Certification Program Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................... 4 Palau Today .................................................................................................... 5 Message from the Koror State Governor ...........................................................6 UNESCO World Heritage Site .............................................................................7 Geography of Palau ...........................................................................................9 Modern Palau ..................................................................................................15 Tourism Network and Activities .......................................................................19 The Tour Guide ............................................................................................. 27 Tour Guide Roles & Responsibilities ................................................................28 Diving Briefings ...............................................................................................29 Responsible Diving Etiquette ...........................................................................30 Coral-Friendly Snorkeling Guidelines ...............................................................30 Best Practice Guidelines for Natural Sites ........................................................33 Communication and Public Speaking ..............................................................34 -

NGARAMEKETII/RUBEKUL KLDEU and IDID CLAN, Appellants, V

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PALAU APPELLATE DIVISION NGARAMEKETII/RUBEKUL KLDEU and IDID CLAN, Appellants, v. KOROR STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY, Appellee. Cite as: 2016 Palau 19 Civil Appeal No. 15-010 Appeal from LC/B 09-068 Decided: July 26, 2016 Counsel for Appellant Ngarameketii/Rubekul Kldeu .................................... Mariano W. Carlos Idid Clan .................................................................... Salvador Remoket Counsel for Appellee ....................................................... Natalie Durflinger BEFORE: ARTHUR NGIRAKLSONG, Chief Justice KATHLEEN M. SALII, Associate Justice HONORA E. REMENGESAU RUDIMCH, Associate Justice Pro Tem Appeal from the Land Court, the Honorable C. Quay Polloi, Senior Judge, presiding. OPINION PER CURIAM:1 [¶ 1] This appeal arises from the Land Court’s award of Ulong Island2 in Koror State to Appellee Koror State Public Lands Authority (“KSPLA”). Appellants Ngarameketii/Rubekul Kldeu (“NRK”) and Idid Clan, both claimants in the case below, now appeal, arguing that the Land Court erred by rejecting their claims. For the reasons that follow, we affirm. 1 We determine that oral argument is unnecessary to resolve this matter. ROP R. App. P. 34(a). 2 Ulong Island consists of Lots 001 through 008 on BLS Worksheet Map Ulong Island. Ngarameketii/Rubekul Kldeu v. Koror State Pub. Lands Auth., 2016 Palau 19 BACKGROUND [¶ 2] The Land Court’s decision provided a detailed account of what is known of pre-contact Ulong, an overview of the historically significant events that occurred on Ulong when the crew of the packet ship Antelope, led by Captain Henry Wilson, took refuge there in 1783, and a summary of Ulong’s history since 1885 when Spain began its administration of Palau. -

The Cinema of Virtuality: the Untimely Avant-Garde of Matsumoto Toshio

The Cinema of Virtuality: The Untimely Avant-Garde of Matsumoto Toshio by Joshua Scammell A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario © 2016, Joshua Scammell Abstract: Scholarship on the avant-garde in Japanese cinema tends to focus on the 1960s. Many scholars believe that the avant-garde vanishes from Japanese cinema in the early 1970s. This study aims to disrupt such narratives with the example of filmmaker/theorist Matsumoto Toshio. Matsumoto is one of the key figures of the 1960s political avant-garde, and this study argues that his 1970s films should also be considered part of the avant-garde. Following Yuriko Furuhata who calls the avant-garde of the 1960s “the cinema of actuality,” this thesis calls the avant-garde of the 1970s “the cinema of virtuality.” The cinema of virtuality will be seen to emphasize a particular type of contiguity with the spectator. This strategy will be discussed in relation to four of Matsumoto’s short films: Nishijin (1961), For the Damaged Right Eye (1968), Atman (1975), and Sway (1985) and a brief discussion of Funeral Parade of Roses (1969). ii Acknowledgements: In the classical world, artists often had their pupils do the actual work, while they took all the credit for the original idea. Working with Aboubakar Sanogo is almost the opposite. No words can express my gratitude towards his generous commitment of time and energy towards this project, and his nurturing open-mindedness to my more abstract ideas. -

Airai State Government V. Iluches, 6 ROP Intrm. 57

Airai State Government v. Iluches, 6 ROP Intrm. 57 (1997) AIRAI STATE GOVERNMENT and AIRAI STATE PUBLIC LANDS AUTHORITY (ASPLA), both represented herein by GOVERNOR, CHARLES I. OBICHANG who is also Chairman of ASPLA, Appellants, v. TITUS ILUCHES, ROMAN TMETUCHL, and TATSUO KAMINGAKI, Appellees. CIVIL APPEAL NO. 26-95 Civil Action No. 120-94 Supreme Court, Appellate Division Republic of Palau Opinion Decided: January 30, 1997 Counsel for Appellants: John K. Rechucher. ⊥58 Counsel for Appellees: Johnson Toribiong BEFORE: ARTHUR NGIRAKLSONG, Chief Justice; JEFFREY L. BEATTIE, Associate Justice; LARRY W. MILLER Associate Justice MILLER, Justice: In this action, Airai State Government and Airai State Public Lands Authority (ASPLA) seek to invalidate a lease previously entered into by ASPLA prior to the invalidation of the first Airai Constitution in the Teriong case. Looking backward from Teriong, they contend that the lease is invalid because the then-existing Airai State Government and ASPLA were invalid governmental entities at the time the lease was entered into. The trial court rejected this contention and they now appeal. We affirm. BACKGROUND The facts of this case are not in dispute. In 1985, Roman Tmetuchl, in his capacity as governor, applied for and received a permit to dredge and fill submerged coastal land near the Koror-Babeldaob Bridge in Airai; this “fill land” was to be the site of the Airai State Marina. On May 1, 1987, Tmetuchl, in his personal capacity, entered into a long-term lease agreement with ASPLA under which he obtained the right to use the subject land for a term of 99 years at a rate Airai State Government v. -

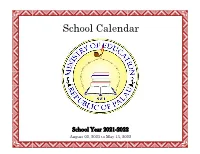

School Calendar 2021-2022 6.27.2020

School Calendar School Year 2021-2022 August 02, 2021 to May 13, 2022 MOE Vision & Mission Statements, Important Dates & Holidays STATE HOLIDAYS MINISTRY OF EDUCATION August 15 Peleliu State Liberation Day August 30 Aimeliik: Alfonso Rebechong Oiterong Day VISION STATEMENT: Cherrengelel a osenged el kirel a skuul. September 11 Peleliu State Constitution Day September 13 Kayangel State Constitution Day September 13 Ngardmau Memorial Day A rengalek er a skuul a mo ungil chad er a Belau me a beluulechad. September 28 Ngchesar State Memorial Day Our students will be successful in the Palauan society and the world. October 01 Ngardmau Constitution Day October 08 Angaur State Liberation Day MISSION STATEMENT: Ngerchelel a skuul er a Belau. October 08 Ngarchelong State Constitution Day October 21 Koror State Constitution Day November 05 Ngarchelong State Memorial Day A skuul er a Belau, kaukledem ngii me a rengalek er a skuul, rechedam me November 02 Angaur State Memorial Day a rechedil me a buai, a mo kudmeklii a ungil el klechad er a rengalek er a November 04 Melekeok State Constitution Day skuul el okiu a ulterekokl el suobel me a ungil osisechakl el ngar er a ungil November 17 Angaur: President Lazarus Salii Memorial Day el olsechelel a omesuub. November 25 Melekeok State Memorial Day November 27 Peleliu State Memorial Day January 06 Ngeremlengui State Constitution Day The Republic of Palau Ministry of Education, in partnership with students, January 12 Ngaraard State Constitution Day parents, and the community, is to ensure student success through effective January 23 Sonsorol State Constitution Day curriculum and instruction in a conducive learning environment.