Interpreting Religious Symbols As Basic Component of Social Value Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

1Changes in Religious Tourism in Poland at The

ISSN 0867-5856 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/0867-5856.29.2.09 e-ISSN 2080-6922 Tourism 2019, 29/2 Franciszek Mróz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6380-387X Pedagogical University of Krakow Institute of Geography Department of Tourism and Regional Studies [email protected] CHANGES IN RELIGIOUS TOURISM IN POLAND AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 21ST CENTURY Abstract: This study presents changes in religious tourism in Poland at the beginning of the 21st century. These include the develop- ment of a network of pilgrimage centers, the renaissance of medieval pilgrim routes, the unflagging popularity of pilgrimages on foot as well as new forms using bicycles, canoes, skis, scooters, rollerblades and trailskates; along with riding, Nordic walking, running and so on. Related to pilgrimages, there is a growing interest in so-called ‘holidays’ in monasteries, hermitages and retreat homes, as well as a steady increase in weekend religious tourism. Religious tourists and pilgrims are attracted to shrines by mysteries, church fairs and religious festivals, in addition to regular religious services and ceremonies. Keywords: religious tourism, pilgrimages, shrine, pilgrim routes, Camino de Santiago (Way of St James). 1. INTRODUCTION Religious tourism is one of the most rapidly developing This article reviews the main trends and changes in types in the world. According to data from the World religious tourism and pilgrimage in Poland at the be- Tourism Organization (UNWTO) from 2004, during ginning of the 21st century. It is worth noting that in the that year approx. 330 million people took trips with analyzed period a number of events took place which a religious or religious-cognitive aim by visiting major have left a mark on the pilgrimage movement and reli- world pilgrimage centers (Tourism can protect and pro- gious tourism in Poland: the last pilgrimage of John mote religious heritage, 2014). -

Towards a Deleuzian Approach in Urban Design

Difference and Repetition in Redevelopment Projects for the Al Kadhimiya Historical Site, Baghdad, Iraq: Towards a Deleuzian Approach in Urban Design A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE In the School of Architecture and Interior Design Of the college of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2018 By Najlaa K. Kareem Bachelor of Architecture, University of Technology 1999 Master of Science in Urban and Regional Planning, University of Baghdad 2004 Dissertation Committee: Adrian Parr, PhD (Chair) Laura Jenkins, PhD Patrick Snadon, PhD Abstract In his book Difference and Repetition, the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze distinguishes between two theories of repetition, one associated with the ‘Platonic’ theory and the other with the ‘Nietzschean’ theory. Repetition in the ‘Platonic’ theory, via the criterion of accuracy, can be identified as a repetition of homogeneity, using pre-established similitude or identity to repeat the Same, while repetition in the ‘Nietzschean’ theory, via the criterion of authenticity, is aligned with the virtual rather than real, producing simulacra or phantasms as a repetition of heterogeneity. It is argued in this dissertation that the distinction that Deleuze forms between modes of repetition has a vital role in his innovative approaches to the Nietzschean’s notion of ‘eternal return’ as a differential ontology, offering numerous insights into work on issues of homogeneity and heterogeneity in a design process. Deleuze challenges the assumed capture within a conventional perspective by using German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s conception of the ‘eternal return.’ This dissertation aims to question the conventional praxis of architecture and urban design formalisms through the impulse of ‘becoming’ and ‘non- representational’ thinking of Deleuze. -

The Restoration of Sanctuaries in Attica, Ii

THE RESTORATIONOF SANCTUARIESIN ATTICA, II The Structure of IG IJ2, 1035 and the Topography of Salamis J[N a previousarticle ' I offered a new study of the text and date of this inscrip- tion. That study has made possible a treatment of the significance of the document for the topography of Attica, particularly Salamis. As I hope to show, both the organization and the contents of the decree, which orders the restoration of sacred and state properties which had fallen into private hands, offer clues to help fix the location of some ancient landmarks. THE DECREES There are two decrees on the stone. The first ends with line 2a, to which line 3 is appended to record the result of the vote. A second, smaller fragment of the stele bears lettering identifiable as belonging to this first decree; 2 since it shows traces of eight lines of text, the decree can have had no less. The maximum length of the original would be about twenty lines, as more would imply an improb- ably tall stele.3 The text of this first decree is too fragmentary to permit a firm statement of its purpose, but one may venture a working hypothesis that it was the basic resolution of the demos to restore the properties, while the second decree was an implementation of that resolution. In support of that view I offer the following considerations: 1) The two decrees were apparently passed at the same assembly, as may be inferred from the abbreviated prescript of the second one; ' 2) although the second decree was probably longer, the first was more important; a record was made of the vote on it but not of the vote on the subsequent resolution; 3) since the second decree clearly provides for the cleansing, rededication and perpetual ten- dance of the sanctuaries, the only more important item possible would be the basic 1 G. -

A Shinto Shrine Turned Local: the Case of Kotohira Jinsha Dazaifu Tenmangu and Its Acculturation on O'ahu

A SHINTO SHRINE TURNED LOCAL: THE CASE OF KOTOHIRA JINSHA DAZAIFU TENMANGU AND ITS ACCULTURATION ON O'AHU A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION MAY 2018 By Richard Malcolm Crum Thesis Committee: Helen Baroni, Chairperson Michel Mohr Mark McNally ABSTRACT This project examines the institution of Hawai’i Kotohira Jinsha Dazaifu Tenmangu in Honolulu as an example of a New Religious Movement. Founded in Hawai`i, the shrine incorporated ritual practices from Sect Shinto customs brought to the islands by Japanese immigrants. Building on the few available scholarly studies, I hypothesize that while Hawai`i Kotohira Jinsha Dazaifu Tenmangu takes the ritual conduct, priestly training, and the festival calendar from a Japanese mainland style of Shinto, the development of the shrine since its foundation in 1920 to the present reflects characteristics of a New Religious Movement. Elements such as the location of the shrine outside of Japan, attendee demographics, non-traditional American and Hawaiian gods included in the pantheon, the inclusion of English as the lingua-franca during festivals and rituals, and the internal hierarchy and structure (both political and physical) lend to the idea of Hawaiian Shinto being something unique and outside of the realm of Sect, Shrine, or State Shinto in Japan. i Table of Contents Introduction Local Scholarship Review, the Hawaiian Islands, and Claims…………………………………….1 How do we define -

July 28, 2019

July 28, 2019 Rev. Msgr. James C. Gehl, Pastor Fr. Anselm Nwakuna, Resident Senior Deacon Mike Perez & Margie Perez MASSES Monday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday: 8:15am Tuesday, Thursday: 6:30am HOLY DAYS: 6:30am, 8:15am and 7:00pm Saturday: 5:30pm Sunday: 8:30, 10:30am and 5:30pm (hosted by Youth Ministry) SACRAMENT OF PENANCE Saturdays: 4:00 to 4:45pm BAPTISMS: Pre-Baptism class for parents and godparents on the first Sunday of every month at 1:00pm in the Church. Baptisms are held on the third Sunday of every month at 1:00pm. MARRIAGE: Please call the Rectory at least six months before the desired wedding day to begin marriage preparation. MASS INTENTIONS FOR THE WEEK PLEASE PRAY FOR John Cook, Marie Stearns, Janet Meyers, Jennie Saturday, July 27th Sorenson, Patricia Valle, Dr. Rosemary Flores, Jerry 8:15am Maudelene Sutton (D) Lowe-Oadell, Janet Ogier, Carol Schafer, Patricia 5:30pm Michael Luszczak (D) Somerville, Werner Kessling, Devin Bundy, Rosa Maria Santos, Nancy Shanahan, Brian Barnes, Zak Sunday, July 28th Morris, Joan Page, Joan Johnson, Marylin McCafferty, George Edgington, Roger Ong, 8:30am The Prayer Line & Margot Sant, Rosa Godinez, Candace Nicholson, The Parish Book of Prayers Daniel Perez, Anton Holzmann, Mark Smith and all Pat Coscia (D) those in our Parish Book of Prayers 1st Anniversary of Passing 10:30am Sara Vargis (D) PLEASE PRAY FOR THE HAPPY 4th Anniversary of Passing REPOSE OF ALL SOULS: 5:30pm Tony Colletti (L) 17th SUNDAY IN ORDIANRY TIME JULY 28, 2019 Happy 28th Birthday! Donald Benson (L) SUNDAY'S READINGS Happy Birthday! First Reading: [Abraham] persisted: "Please, do not let my Lord grow angry if I speak up this Monday, July 29th last time." (Gn 18:32) 8:15am Edwardo Escolano (D) Psalm: Lord, on the day I called for help, you answered me. -

The Dominion of the Dead: Power Dynamics and the Construction of Christian Cultural Memory at the Fourth-Century Martyr Shrine

The Dominion of the Dead: Power Dynamics and the Construction of Christian Cultural Memory at the Fourth-Century Martyr Shrine by Nathaniel J. Morehouse A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Religion University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2012 Nathaniel J. Morehouse P a g e | ii Abstract This thesis is aimed at addressing a lacuna in previous scholarship on the development of the martyr cult in the pivotal fourth century. Recent work on the martyr cult has avoided a diachronic approach to the topic. Consequently through their synchronic approach, issues of the early fifth century have been conflated and presented alongside those from the early fourth, with little discussion of the development of the martyr cult during the intervening decades. One aim of this work is to address the progression of the martyr cult from its pre-Christian origins through its adaptations in the fourth and early fifth century. Through a discussion of power dynamics with a critical eye towards the political situation of various influential figures in the fourth and early fifth centuries, this thesis demonstrates the ways in which Constantine, Damasus, Ambrose, Augustine, and others sought to craft cultural memory around the martyr shrine. Many of them did this through the erection of structures over pre-existing graves. Others made deliberate choices as to which martyrs to commemorate. Some utilized the dissemination of the saints’ relics as a means to expanding their own influence. Finally several sought to govern which behaviours were acceptable at the martyrs’ feasts. -

Sectarian Violence: Radical Groups Drive Internal Displacement in Iraq

The Brookings Institution—University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement Sectarian Violence: Radical Groups Drive Internal Displacement in Iraq by Ashraf al-Khalidi and Victor Tanner An Occasional Paper October 2006 Sectarian Violence: Radical Groups Drive Internal Displacement in Iraq by Ashraf al-Khalidi and Victor Tanner THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION – UNIVERSITY OF BERN PROJECT ON INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington DC 20036-2188 TELEPHONE: 202/797-6168 FAX: 202/797-6003 EMAIL: [email protected] www.brookings.edu/idp I will never believe in differences between people. I am a Sunni and my wife is a Shi‘a. I received threats to divorce her or be killed. We left Dora [a once-mixed neighborhood in Baghdad] now. My wife is staying with her family in Sha‘b [a Shi‘a neighborhood] and I am staying with my friends in Mansur [a Sunni neighborhood]. I am trying to find a different house but it's difficult now to find a place that accepts both of us in Baghdad. A young Iraqi artist, Baghdad, June 2006 About the Authors Ashraf al-Khalidi is the pseudonym of an Iraqi researcher and civil society activist based in Baghdad. Mr. Khalidi has worked with civil society groups from nearly all parts of Iraq since the first days that followed the overthrow of the regime of Saddam Hussein. Despite the steady increase in violence, his contacts within Iraqi society continue to span the various sectarian divides. He has decided to publish under this pseudonym out of concern for his security. Victor Tanner conducts assessments, evaluations and field-based research specializing in violent conflict. -

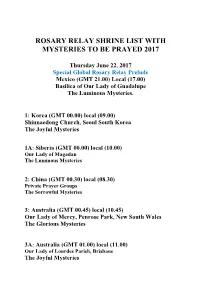

Rosary Relay Shrine List with Mysteries to Be Prayed 2017

ROSARY RELAY SHRINE LIST WITH MYSTERIES TO BE PRAYED 2017 Thursday June 22, 2017 Special Global Rosary Relay Prelude Mexico (GMT 21.00) Local (17.00) Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe The Luminous Mysteries. 1: Korea (GMT 00.00) local (09.00) Shinnaedong Church, Seoul South Korea The Joyful Mysteries 1A: Siberia (GMT 00.00) local (10.00) Our Lady of Magadan The Luminous Mysteries 2: China (GMT 00.30) local (08.30) Private Prayer Groups The Sorrowful Mysteries 3: Australia (GMT 00.45) local (10.45) Our Lady of Mercy, Penrose Park, New South Wales The Glorious Mysteries 3A: Australia (GMT 01.00) local (11.00) Our Lady of Lourdes Parish, Brisbane The Joyful Mysteries 3B: India (GMT 01.00) local (6.30) Carmelite Community, Northern India The Luminous Mysteries 4: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) The Shrine of Mary, at Pukekaraka Otaki The Sorrowful Mysteries 4A: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) Carmelite Monastery, Aukland The Glorious Mysteries 4B: Thailand (01.45) local (8.45) St. Raphael Kalinowski Carmelite Priory Chapel of the Infant Jesus in Sampran. Glorious Mysteries 5: Singapore (GMT 02.00) local (10.00) Good Shepherd Convent Chapel The Joyful Mysteries 6: Brunei (GMT 02.30) local (10.30) Church of Our Lady’s Assumption The Luminous Mysteries 6A: Vietnam (GMT 02.45) local (09.45) Our Lady of La Vang The Sorrowful Mysteries 7: Philippines (GMT 03.00) local (11.00). The National Shrine of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, New Manila, Quezon City The Glorious Mysteries 8: Philippines (GMT 03.30) local (11.30) Shrine of the -

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement

Encyclopedia of Shinto Chronological Supplement 『神道事典』巻末年表、英語版 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics Kokugakuin University 2016 Preface This book is a translation of the chronology that appended Shinto jiten, which was compiled and edited by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. That volume was first published in 1994, with a revised compact edition published in 1999. The main text of Shinto jiten is translated into English and publicly available in its entirety at the Kokugakuin University website as "The Encyclopedia of Shinto" (EOS). This English edition of the chronology is based on the one that appeared in the revised version of the Jiten. It is already available online, but it is also being published in book form in hopes of facilitating its use. The original Japanese-language chronology was produced by Inoue Nobutaka and Namiki Kazuko. The English translation was prepared by Carl Freire, with assistance from Kobori Keiko. Translation and publication of the chronology was carried out as part of the "Digital Museum Operation and Development for Educational Purposes" project of the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Organization for the Advancement of Research and Development, Kokugakuin University. I hope it helps to advance the pursuit of Shinto research throughout the world. Inoue Nobutaka Project Director January 2016 ***** Translated from the Japanese original Shinto jiten, shukusatsuban. (General Editor: Inoue Nobutaka; Tokyo: Kōbundō, 1999) English Version Copyright (c) 2016 Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University. All rights reserved. Published by the Institute for Japanese Culture and Classics, Kokugakuin University, 4-10-28 Higashi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan. -

Download Factly Magazine For–Nov. 2018

MONTHLY FACTLY EXCLUSIVE CURRENT AFFAIRS FOR PRELIMS NOVEMBER 2018 Page 1 of 55 INDEX POLITICAL AND NATIONAL ISSUES 1. Enemy Property 2. Freedom on the Net Report 2018 3. Governor’s Assembly Dissolution Powers 4. Parliamentary Privileges 5. NOTA 6. States v/s CBI INTERNATIONAL ISSUES 1. US waiver for India 2. G20 summit 3. BITA 4. India-Australia 5. Generalised System of Preferences 6. Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation 7. East Asia Summit 8. BREXIT 9. Afghan Peace Conference 10. Kartarpur Corridor GOVERNMENT SCHEMES 1. YUVA Sahakar-Cooperative Enterprise Support and Innovation Scheme 2. Data City Programme 3. PAISA Portal ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS 1. Credit Rating Agencies 2. National Financial Reporting Authority 3. Ease of Doing Business Report 2018 4. World Development Report 5. Human Capital Index 6. Sustainable Blue Economy Conference 7. Guidelines for Operation Greens 8. SEZ Policy Report 9. Capital Conservation Buffer 10. ECB norms 11. Legal Entity Identifier 12. Credit Enhancement for Bonds by NBFCs and HFCs 13. Advanced Motor Fuel Technology Collaboration Programme 14. Petroleum, Chemicals and Petrochemical Investment Regions 15. First Multi-Modal Terminal on Inland Waterways 16. Maharashtra ending the APMC Monopoly 17. MSME Outreach Programme Current Affairs 2019 Classes by ForumIAS 2nd Floor, IAPL House, 19, Pusa Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi – 110005 | [email protected]|982171160 Page 2 of 55 18. City Gas Distribution 19. Application Programming Interface Exchange (APIX) SOCIAL DEVELOPMENTS 1. Safe City Project 2. Emergency Response Support System 3. Location Tracking and Emergency Buttons 4. South Asian Regional Conference on Urban Infrastructure 5. Dubai Declaration 6. Global Wage Report 7. -

Shrines and Pilgrimages in Poland As an Element of the “Geography” of Faith and Piety of the People of God in the Age of Vatican II (C

religions Article Shrines and Pilgrimages in Poland as an Element of the “Geography” of Faith and Piety of the People of God in the Age of Vatican II (c. 1948–1998) Franciszek Mróz Institute of Geography, Pedagogical University of Krakow, 30-084 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] Abstract: This research is aimed at learning about the origins and functions of shrines, and changes to the pilgrimage movement in Poland during the Vatican II era (c. 1948–1998). The objective required finding and determining the following: (1) factors in the establishment of shrines in Poland during this time; (2) factors in the development of shrines with reference to the transformation of religious worship and to the influence of political factors in Poland; (3) changes in pilgrimage traditions in Poland, and (4) changes in the number of pilgrimages to selected shrines. These changes were determined by archive and library research. Additionally, field studies were performed at more than 300 shrines, including observations and in-depth interviews with custodians. Descriptive–analytical, dynamic–comparative and cartographic presentation methods were used to analyze results. Keywords: pilgrimage; popular piety; sacred place; shrines; Vatican II Citation: Mróz, Franciszek. 2021. 1. Introduction Shrines and Pilgrimages in Poland as Pilgrimages are some of the oldest and most permanent religious practices in all major an Element of the “Geography” of religions around the world (Chélini and Branthomme 1982; Collins-Kreiner 2010; Timothy Faith and Piety of the People of God and Olsen 2006). Since the beginning of the history of mankind, pilgrimages to sacred in the Age of Vatican II (c.