Original Paper Jestersin Shakespeare's Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Lyrics of the Henry VIII Manuscript

The English Lyrics of the Henry VIII Manuscript by RAYMOND G. SIEMENS B. A. (Hons), The University of Waterloo, 1989 M.A., The University of Alberta, 1991 A THESIS SUBMITTED LN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES, Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May 20, 1997 ©R.G. Siemens, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or 'by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. /7 v. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2788) Abstract The Henry VIII MS (BL Additional MS 31,922)—a song book with lyrics by Henry VIII, Thomas Wyatt, William Cornish, and other literary figures of the early Henrician court—is a document that contributes greatly to a critical understanding of the connections between poetry, patronage, and power in early Renaissance society because of the prominence of its chief author, the King himself, and the manuscript's reflection of literary, social, and political elements of the early Tudor court. Acknowledging that the contents of the Henry VIII MS have been thoroughly treated as "words for music" by the musicologist John Stevens, whose Music and Poetry in the Early Tudor Court and Music at the Court of Henry VIII are the standard works in the area, my thesis builds on existing scholarship to treat the lyrics of H chiefly as "words," as literary texts. -

The Deacon As Wise Fool: a Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate

ATR/100.4 The Deacon as Wise Fool: A Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate Kevin J. McGrane* Deacons often sit with the hurt and marginalized. It is in keeping with our ordination vows as deacons in the Episcopal Church, which say, “God now calls you to a special ministry of servanthood. You are to serve all people, particularly the poor, the weak, the sick, and the lonely.”1 Ever task focused, deacons look for the tangible and concrete things we can do to respond to the needs of the least of Jesus’ broth- ers and sisters (Matt. 25:40). But once the food is served, the money given, the medicine dispensed, then what? The material needs are supplied, but the hurt and the trauma are still very much present. What kind of pastoral care can deacons bring that will respond to the needs of the hurting and traumatized? I suggest that, if we as deacons are going to be sources of contin- ued pastoral care beyond being simple providers of material needs, we need to look to the pastoral model of the wise fool for guidance. With some exceptions here and there, deacons are uniquely fit to practice the pastoral persona of the wise fool. The wise fool is a clinical pastoral persona most identified and de- veloped by the pastoral theologians Alastair V. Campbell and Donald Capps. The fool is an archetype in human culture that both Campbell and Capps view as someone capable of rendering pastoral care. In his essay “The Wise Fool,”2 Campbell describes the fool as a “necessary figure” to counterpoint human arrogance, pomposity, and despo- tism: “His unruly behavior questions the limits of order; his ‘crazy’ outspoken talk probes the meaning of ‘common sense’; his uncon- ventional appearance exposes the pride and vanity of those around * Kevin J. -

TRANSITION from CORAMBIS to POLONIUS the Forgotten Pun on a Diplomatic Scandal in a Hamlet Q2 Stage Direction Abraham Samuel

TRANSITION FROM CORAMBIS TO POLONIUS The Forgotten Pun on a Diplomatic Scandal in a Hamlet Q2 Stage Direction Abraham Samuel Shiff 1. Introduction Angered, Queen Elizabeth furiously chastised the audacious Polish ambassador Paulus Dzialinski (Paweł Działyński) with a Latin phrase that became a metaphor for insolence to a superior by a subordinate: Quam decepta fui? Legatum expectavi, Heraldum inveni – Why am I deceived? I expected a Legate, I found a Herald! Shakespeare introduced a pun into the Hamlet second quarto (Q2) of 1604/5 to mock the offending ambassador. The passage of time and a compositor's error in the first folio (F1) edition of 1623 obscured the reference to the 1597 diplomatic scandal. This essay explains the incident, the pun that it generated, and the consequence of the printer's error.* 2. Source Documents The 1597 diplomatic incident is well documented. Eyewitness testimony of the insult and Elizabeth's reaction is in a letter from Cecil to Essex.1 The Privy Council's minutes book2 and Cecil's archives preserved in Hatsfield House3 contain entries pertaining to the ambassador. ________________________ * Derived from Polonius Identified: Scandal to Pun to Gossip to Print, a thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts, accepted in December 2009 by the Department of Liberal Studies of the Graduate Center, City University of New York. It is my pleasure to acknowledge the guidance of: Professor Margaret King―my adviser for two thesis on unrecognized Hamlet metaphors; Professor Andrew Majeske―whose encouragement enabled the writing of this paper. Professor Wladyslaw Roczniak―for his kind introduction to Polish works and sources; Barbara Lekisch― for her graciously shared information about Thomas Davies; and Professor Ari Cohen―a friend of many years who is always available to read a draft, this paper is improved by his many critical suggestions. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

Class Clown and Court Jester: a Case Study Approach to the Tradition of the Fool

CLASS CLOWN AND COURT JESTER: A CASE STUDY APPROACH TO THE TRADITION OF THE FOOL By DAVID CHEVREAU B.A., York University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Counselling Psychology We accept this Thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1994 © David Chevreau, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of (jOO^fr^fr ^SfObL^y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date Apm- ^ 1*T^ DE-6 (2/88) -ii- ABSTRACT Though he is well known, the Class Clown is not particularly well understood. With the exception of one quantitative study by Damingo and Purkey (1978), no significant research has been written on this witty character. The educational community has viewed the Class Clown by and large as an under-achieving student who, in his efforts to get attention, is a disruptive force in the classroom. As such, his behaviour, though often enormously funny, is a threat to the conformity and stability that good classroom discipline demands. -

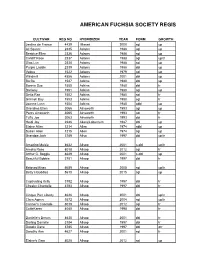

Regn Lst 1948 to 2020.Xls

AMERICAN FUCHSIA SOCIETY REGISTERED FUCHSIAS, 1948 - 2020 CULTIVAR REG NO HYBRIDIZER YEAR FORM GROWTH Jardins de France 4439 Massé 2000 sgl up All Square 2335 Adams 1988 sgl up Beatrice Ellen 2336 Adams 1988 sgl up Cardiff Rose 2337 Adams 1988 sgl up/tr Glas Lyn 2338 Adams 1988 sgl up Purple Laddie 2339 Adams 1988 dbl up Velma 1522 Adams 1979 sgl up Windmill 4556 Adams 2001 dbl up Bo Bo 1587 Adkins 1980 dbl up Bonnie Sue 1550 Adkins 1980 dbl tr Dariway 1551 Adkins 1980 sgl up Delta Rae 1552 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Grinnell Bay 1553 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Joanne Lynn 1554 Adkins 1980 sdbl up Grandma Ellen 3066 Ainsworth 1993 sgl up Percy Ainsworth 3065 Ainsworth 1993 sgl tr Tufty Joe 3063 Ainsworth 1993 dbl tr Heidi Joy 2246 Akers/Laburnum 1987 dbl up Elaine Allen 1214 Allen 1974 sdbl up Susan Allen 1215 Allen 1974 sgl up Grandpa Jack 3789 Allso 1997 dbl up/tr Amazing Maisie 4632 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up/tr Amelia Rose 8018 Allsop 2012 sgl tr Arthur C. Boggis 4629 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up Beautiful Bobbie 3781 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Beloved Brian 5689 Allsop 2005 sgl up/tr Betty’s Buddies 8610 Allsop 2015 sgl up Captivating Kelly 3782 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cheeky Chantelle 3783 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cinque Port Liberty 4626 Allsop 2001 dbl up/tr Clara Agnes 5572 Allsop 2004 sgl up/tr Conner's Cascade 8019 Allsop 2012 sgl tr CutieKaren 4040 Allsop 1998 dbl tr Danielle’s Dream 4630 Allsop 2001 dbl tr Darling Danielle 3784 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Doodie Dane 3785 Allsop 1997 dbl gtr Dorothy Ann 4627 Allsop 2001 sgl tr Elaine's Gem 8020 Allsop 2012 sgl up Generous Jean 4813 -

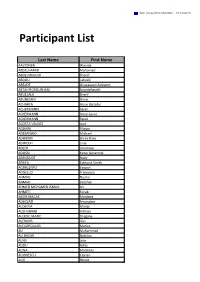

Participant List

Ref. Ares(2015)5922007 - 17/12/2015 Participant List Last Name First Name AALTONEN Wanida ABDELHAMID Mohamed ABDELMEGUID Sheref ABDOU Lahadji ABEJIDE Oluwaseun Adeyemi ABTAHIFOROUSHANI Seyedehasieh ABUELALA Sherif ABUNEMEH Omar ACHARYA Arjun Bahadur ACHERMANN Sarah ACKERMANN Anne-Laure ACKERMANN Raoul ACOSTA VALDEZ Jose ADDARII Filippo ADESANWO Michael ADHIKARI Shree Ram ADINOLFI Livia ADLER Jéromine ADOSSI Yawo Nevemde AERNOUDT Rudy AFRIFA Edmund Smith AGBALENYO Yawovi AGNELLO Francesca AHMAD Najma AHMAD Zeeshan AHMED MOHAMED ISMAIL Ali AHMETI Korab AKSIN MACAK Marijana ALBIZZATI Amandine ALCHEVA Marija ALDHUBAIBI Hitham ALEKSIC MATIC Dragana ALEXAKIS Ilias ALEXOPOULOS Marios ALI Muhammad ALI BACAR Nabilou ALIAS Jose ALIDU Adilu ALINA Marinoiu ALIONESCU Ciprian ALIX Nicole ALLET Marion ALMAZYAN Lida ALMEIDA Katia ALONSO Beatriz ALSAWALAH Abedallah ALTINOK Salih ALVARADO TANAMACHI Sayuri ALVAREZ Ana ALVES Filipe AMADIO Nicolas AMALFITANO Marie AMAZIT Anaïs AMBROSIO Giuseppe AMET Suzon AMITSIS Gabriel ANASTOPOULOS Konstantinos ANCA Gunta ANCEL Florian ANDRES Rodolphe ANDREU Tomás ANDREW Mwebaza ANDRICOPOULOU Anna ANDRIOT Patricia ANDRITSOU Anastasia ANESE Tobia ANGELOVA Milena ANNE Leautier ANSELM Cecile APOLLONI Guglielmo APOSTOLIDIS Catherine APPEL Ulrik ARNOLD David AROYAN Luciné ARREGUI Karin Arriaga Sierra Hermes ARROYO DE SANDE Carmen ARVANITI Chrysafo ASCHARI-LINCOLN Jessica ASLAN Ayse ASRAF Adeeba ASSABA Inès ATAMAN SCHARNING Ayşegül ATAYI Ayoko Veronique ATHANASIADOU Natasha Marie AUCONIE Sophie AUGER Christophe AVENTAGGIATO Giovanni -

Till Eulenspiegel As a “Recurring Character” in the Works of Hans Sachs

Narrative Arrangement in 16th-Century Till Eulenspiegel Texts: The Reinvention of Familiar Structures A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Isaac Smith Schendel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Dr. Anatoly Liberman June 2018 © Isaac Smith Schendel 2018 i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. Anatoly Liberman, for his kind direction, ideas, and guidance through the entire process of graduate school, from the first lectures on Middle High German grammar and Scandinavian Literature, to the preliminary exams, prospectus and multiple thesis drafts. Without his watchful eye, advice, and inexhaustible patience, this dissertation would have never seen the light of day. Drs. James A. Parente, Andrew Scheil, and Ray Wakefield also deserve thanks for their willingness to serve on the committee. Special gratitude goes to Dr. Parente for reading suggestions and leadership during the latter part of my graduate school career. His practical approach, willingness to meet with me on multiple occasions, and ability to explain the intricacies of the university system are deeply appreciated. I have also been helped by a number of scholars outside of Minnesota. The material discussed in the second chapter of the dissertation is a reformulated, expanded, and improved version of my article appearing in Daphnis 43.2. Although the central thesis is now radically different, I would still like to thank Drs. Ulrich Seelbach and Alexander Schwarz for their editorial work during that time, especially as they directed my attention to additional information and material within the S1515 chapbook. -

Project Summer Read 2020

Project SUMMER Read 2020 SUMMER READING SUGGESTIONS AND RESOURCES SUGERENCIAS DE LECTURE VERANO Y RECURSOS Elementary K-5 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read Parent Resources Recursos Para Padres Choosing Books for Children by Betsy Hearne Best of the Best for Children by Denise Perry Donavin, ed. The New Read‐Aloud Handbook by Jim Trelease For Reading Out Loud by Margaret May Kimmel Read to Me: Raising Kids Who Love to Read by Bernice E. Cullinan Parent’s Guide to the Best Books for Children by Eden Ross Lipson Reading Magic by Mem Fox Other Websites Otros sitios web White Plains Public Schools whiteplainspublicschools.org Westchester Libraries Online westchesterlibraries.org White Plains Public Library whiteplainslibrary.org White Plains Youth Bureau whiteplainsyouthbureau.org Barnes & Noble Booksellers barnesandnoble.com Common Sense Media commonsensemedia.org 2020 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read WHITE PLAINS PUBLIC SCHOOLS EDUCATION HOUSE FIVE HOMESIDE LANE WHITE PLAINS, NEW YORK 10605 914-422-2000 www.wpcsd.k12.ny.us Joseph L. Ricca, Ed.D. Superintendent of Schools June 2020 Dear Parent/Guardian, Many parents ask: “What can I do to help my child be a better student?” The key to a good education is reading with understanding. If you encourage your child to read, if you read to your child, if you discuss with your child what is being read, your child will develop a love for reading and learning. Reading is both fun and useful. Folktales, sports news, fashion news, business news, celebrity gossip, and comics –it all has value. Our Project Summer Read program is designed to make it easier to select books, for a full summer of reading. -

Α. Μ. Klein's Forgotten Play

Α. Μ. KLEIN'S FORGOTTEN PLAY G. K. Fischer AL. M. KLEIN has always been a writer with a mission; and students of his work know that one of its salient features is found in his effort to wake in the Canadian reader a sympathetic understanding of the world of the Shtetl of Eastern Europe which lives on in the memory and basic attitudes of Yiddish immigrants. His writings attest to his desire to transmit, to recreate, to interpret the traditions which his parents brought from the provincial towns of Poland, traditions which he views with scholarly and compassionate eyes, with the intellect of an educated Canadian, and with the insight of a Jew who recog- nizes in fading customs and half-forgotten legends the eternal verities which once gave rise to them. Among the works which show most clearly Klein's determination to instil new vitality into Yiddish folklore is a short verse play, Hershel of Ostropol. It is an interesting play but, at present, quite unknown, unlisted in most bibliographies, unmentioned in critical essays on Klein's work, completely forgotten, it seems, even by his most devoted readers. There are at least two reasons for this neglect. First, there is the date of publication. The play was printed in The Canadian Jewish Chronicle in March and in September 1939, at a time when Canadians, particularly Jewish Canadians, had more pressing problems on their minds. Secondly, the manner of publication almost guaranteed that any impact the play might have made should be lost. Act One appeared in March; Acts Two and Three appeared more than five months later.1 To my knowledge, there has been no performance of the play. -

Cello Biennale 2018

programmaoverzicht Cellists Harald Austbø Quartet Naoko Sonoda Nicolas Altstaedt Jörg Brinkmann Trio Tineke Steenbrink Monique Bartels Kamancello Sven Arne Tepl Thu 18 Fri 19 Sat 20 Sun 21 Mon 22 Tue 23 Wed 24 Thu 25 Fri 26 Sat 27 Ashley Bathgate Maarten Vos Willem Vermandere 10.00-16.00 Grote Zaal 10.00-12.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal 09.30 Grote Zaal Kristina Blaumane Maya Beiser Micha Wertheim First Round First Round (continued) Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Bach&Breakfast Arnau Tomàs Matt Haimovitz Kian Soltani Jordi Savall Sietse-Jan Weijenberg Harriet Krijgh Lidy Blijdorp Mela Marie Spaemann Santiago Cañón NES Orchestras and Ensembles 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.30-12.45 Grote Zaal 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.15-12.30 10.30 and 12.00 Kleine Zaal Master class Master class Second Round Masterclass Masterclass Masterclass Masterclass Valencia Svante Henryson Accademia Nazionale di Santa Show for young children: Colin Carr (Bimhuis) Jordi Savall (Bimhuis) Jean-Guihen Queyras Nicolas Altstaedt (Bimhuis) Roel Dieltiens (Bimhuis) Matt Haimovitz (Bimhuis) Colin Carr Quartet Cecilia Spruce and Ebony Jakob Koranyi (Kleine Zaal) Giovanni Sollima (Kleine (Bimhuis) Michel Strauss (Kleine Zaal) Chu Yi-Bing (Kleine Zaal) Reinhard Latzko (Kleine Zaal) Zaal) Kian Soltani (Kleine Zaal) Hayoung Choi The Eric Longsworth Amsterdam Sinfonietta 11.00 Kleine Zaal Chu Yi-Bing Project Antwerp Symphony Orchestra Show for young children: -

Santha Cassell Senior Thesis April 17, 1987 the Fool As a Provisional

The Fool As A Provisional Role in shakespeare: Three Examples Santha Cassell Senior Thesis April 17, 1987 In his essay "Jacobean Shakespeare," Maynard Mack explains the system of "mirroring" that produces Shakespeare's depth and unity. A "mirror" is an element that creates a dialogue with other elements, and weaves the thematic fabric of the play. This process takes place between motifs, parallel scenes, and characters who echo each other or "speak each other's minds." l Very often, the mirroring character or catalyst is the licensed fool. with dramatic permission to say anything, and a reputation and tradition of madness, the fool both reveals the truth and obscures it with his inverted, debased, or metaphoric language. Just as an event can perpetuate the plot's development, an encounter with the fool can advance a character's development and our understanding of the play. The wise fool is provisional in the sense that his behavior is dependent on the demands the play places on him. The fool possesses a specific discourse that contrasts with the way the major characters in the play communicate. This dichotomy produces the fool's humor and allows him to perform his dramatic purpose. Bakhtin speaks of the effect in his discussion of genre in Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. In addressing the characteristics of the serio-comical genres he says: In all genres of the serio-comical, to be sure, there is a strong rhetorical element, but in the atmosphere of joyful relativity characteristic of a carnival sense of the world this element is fundamentally changed: there is a weakening of its one-sided rhetorical seriousness, its rationality, its singular meaning, its dogmatism.