The Wisdom of Holy Fools in Postmodernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW PRINCIPAL ELECTED to SUCCEED PRESIDENT H. M. DALE Academy Boys Place •••■•••■••

THE CLARION VOL. VI—No. 10 AUGUSTANA ACADEMY, CANTO N, SOUTH DAKOTA, APRIL 1, 1927 PRICE }O.o, NEW PRINCIPAL ELECTED TO SUCCEED PRESIDENT H. M. DALE Academy Boys Place •••■•••■••..... Reverend Rothnem Third at N. L. C. A. New AucustanaAcademy Principal of Dell Rapids New Basketball Tourney Rev. Botolf J. Rothnem, re- Academy Princilwa. Win in the Consolations cently elected principal of To 'fake Up Duties About July 1 Augustana academy to suc- The academy basket ball team left ceed Prof. H. M. Dlae, was a Monday, March 6, to take part in the Rev. Bottolf Jacob Rothnem, 1a,st-or student at St.' Olaf College, N.L.C.A. basketball tournament to of Dell Rapids for more that nine Northfield, Minn., from 1902 years, was unanimously selected. be held at St. Olaf college on March to 1996. He was a member Tuesday by the board of directors of 7, 8, and 9. of the same class as Pres. J. the Augustana College association to They left about eight o'clock Mon- N. Brown of Concordia col- succeed Prof. H. M. Dale as princi- day morning and landed safely in lege and Prof. H. M. Dale. pal of Augustana academy. After Northfield about 9:30 that evening Rev. Rothnem served as accepting th e position, Rev. Rotl,oeira with no trouble to speak of, except president of the Sioux Falls stated that he expects to be ablr t.o stiff joints and limbs. Here they were circuit of the Norwegian enter upon his duties here about taken care Lutheran church of America of and given rooms in the from 1922 to 1924. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Deacon As Wise Fool: a Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate

ATR/100.4 The Deacon as Wise Fool: A Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate Kevin J. McGrane* Deacons often sit with the hurt and marginalized. It is in keeping with our ordination vows as deacons in the Episcopal Church, which say, “God now calls you to a special ministry of servanthood. You are to serve all people, particularly the poor, the weak, the sick, and the lonely.”1 Ever task focused, deacons look for the tangible and concrete things we can do to respond to the needs of the least of Jesus’ broth- ers and sisters (Matt. 25:40). But once the food is served, the money given, the medicine dispensed, then what? The material needs are supplied, but the hurt and the trauma are still very much present. What kind of pastoral care can deacons bring that will respond to the needs of the hurting and traumatized? I suggest that, if we as deacons are going to be sources of contin- ued pastoral care beyond being simple providers of material needs, we need to look to the pastoral model of the wise fool for guidance. With some exceptions here and there, deacons are uniquely fit to practice the pastoral persona of the wise fool. The wise fool is a clinical pastoral persona most identified and de- veloped by the pastoral theologians Alastair V. Campbell and Donald Capps. The fool is an archetype in human culture that both Campbell and Capps view as someone capable of rendering pastoral care. In his essay “The Wise Fool,”2 Campbell describes the fool as a “necessary figure” to counterpoint human arrogance, pomposity, and despo- tism: “His unruly behavior questions the limits of order; his ‘crazy’ outspoken talk probes the meaning of ‘common sense’; his uncon- ventional appearance exposes the pride and vanity of those around * Kevin J. -

ABSTRACT Love Itself Is Understanding: Balthasar, Truth, and the Saints Matthew A. Moser, Ph.D. Mentor: Peter M. Candler, Jr., P

ABSTRACT Love Itself is Understanding: Balthasar, Truth, and the Saints Matthew A. Moser, Ph.D. Mentor: Peter M. Candler, Jr., Ph.D. This study examines the thought of Hans Urs von Balthasar on the post-Scholastic separation between dogmatic theology and the spirituality of Church, which he describes as the loss of the saints. Balthasar conceives of this separation as a shattering of truth — the “living exposition of theory in practice and of knowledge carried into action.” The consequence of this shattering is the impoverishment of both divine and creaturely truth. This dissertation identifies Balthasar’s attempt to overcome this divorce between theology and spirituality as a driving theme of his Theo-Logic by arguing that the “truth of Being” — divine and creaturely — is most fundamentally the love revealed by Jesus Christ, and is therefore best known by the saints. Balthasar’s attempted re-integration of speculative theology and spirituality through his theology of the saints serves as his critical response to the metaphysics of German Idealism that elevated thought over love, and, by so doing, lost the transcendental properties of Being: beauty, goodness, and truth. Balthasar constructively responds to this problem by re-appropriating the ancient and medieval spiritual tradition of the saints, as interpreted through his own theological master, Ignatius of Loyola, to develop a trinitarian and Christological ontology and a corresponding pneumatological epistemology, as expressed through the lives, and especially the prayers, of the saints. This project will follow the structure and rhythm of Balthasar’s Theo-Logic in elaborating the initiatory movement of his account of truth: phenomenological, Christological, and pneumatological. -

Thomas Merton and Zen 143

Thomas Merton and Zen 143 period of years I talked with Buddhists, with and without interpreters, as well as with Christian experts in Buddhist meditation, in Rome, Tokyo, Kyoto, Bangkok, and Seoul. Then, in 1992, I came across a book on Korean Zen. I do not have the patience for soto Zen. And I had dab bled in rinzai Zen, with the generous and kind help of K. T. Kadawoki at Sophia University in Tokyo; but I was a poor pupil, got nowhere, and gave up quickly. Thomas Merton and Zen I found Korean Zen, a form of rinzai, more aggressive; it insists on questioning. Sitting in the Loyola Marymount University library in Los Angeles, reading a book on Korean Zen, I experienced en Robert Faricy lightenment. And it lasted. Later, my library experience was verified independently by two Korean Zen masters as an authentic Zen en lightenment experience. In the book Contemplative Prayer 1 Thomas Merton presents his In the spring of 1993, after several months of teaching as a mature thought on Christian contemplation. The problem is this: visiting professor at Sogang University in Seoul, I went into the moun Merton's last and most important writing on contemplation can be, tains not far inland from Korea's southern coast to a hermitage of the and often is, misunderstood. Contemplative prayer, as described by main monastery of the Chogye order, Songwang-sa, for three weeks of Merton in the book, can appear solipsistic, self-centered, taking the Zen meditation. It was an intensive and profound experience. Among center of oneself as the object of contemplation, taking the same per other things, it brought me back to another reading of Contemplative son contemplating as the subject to be contemplated. -

Song Lyrics of the 1950S

Song Lyrics of the 1950s 1951 C’mon a my house by Rosemary Clooney Because of you by Tony Bennett Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give Because of you you candy Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give a There's a song in my heart. you Apple a plum and apricot-a too eh Because of you, Come on-a my house, my house a come on My romance had its start. Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house I’m gonna give a Because of you, you The sun will shine. Figs and dates and grapes and cakes eh The moon and stars will say you're Come on-a my house, my house a come on mine, Come on-a my house, my house a come on Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give Forever and never to part. you candy Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give I only live for your love and your kiss. you everything It's paradise to be near you like this. Because of you, (instrumental interlude) My life is now worthwhile, And I can smile, Come on-a my house my house, I’m gonna give you Christmas tree Because of you. Come on-a my house, my house, I’m gonna give you Because of you, Marriage ring and a pomegranate too ah There's a song in my heart. -

Main Ballroom Playlist

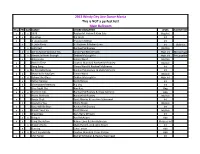

2013 Windy City Line Dance Mania This is NOT a perfect list! Main Ballroom Thur FRI SAT DANCE CHOREOGRAPHER LEVEL TAUGHT BY x x x 1929 Robbie M. Hickie & Kate Sala Beg/Int x x 50 Ways Pat Stott Int x A Liquid Lunch Francien Sittrop Int x A Little Party Jill Babinec & Ruben Luna Int Babinec x Addicted Rachael McEnaney Int/Adv x x Ain't Leaving Without You Linda Paul McCormack High Int McCormack x Almost Is Never Enough Debbie McLaughlin High Int McLaughlin x Americano Simon Ward Int/Adv x Back In Time Guyton Mundy & Rachael McEnaney Int/Adv x Bang Bang Simon Ward & Rachael McEnaney Int x Be My Baby Now Rachael McEnaney & Vicky St Pierre Int x x Beautiful In My Eyes Simon Ward Int/Adv x x Behind the Glass Debbie McLaughlin High Int x Better Believe Scott Blevins Int x Bittersweet Memory Ria Vos Int x Blue Night Cha Kim Ray Beg x x x Blurred Lines Rachael McEnaney & Arjay Centeno Adv x Boom Sh-Boom Rachael McEnaney Int/Adv x Booty Chuk Scott Blevins & Lou Ann Schemmel Int x Bound to You Maria Maag Int/Adv x Boys Will Be Boys Rachael McEnaney Int x x Break Free Cha Scott Blevins Int/Adv x x Breathless Karl-Harry Winson Int x x Bring It Paul McAdam Adv x x Bring the Action Ruben Luna & John Robinson Phrased Int x Broken Heels Mark Furnell, Jo & John Kinser Int x Burning Cato Larson Adv x x Can't Handel Me Guyton Mundy & Carey Parson Adv x Chill Factor Daniel Whitaker & Hayley Westhead Int x x x Clap Happy! Shaz Walton Int x x x Clap Your Hands Joey Warren High Int x x x Come Together 2013 Debbie McLaughlin Adv x Coolio Rachael McEnaney & Arjay -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Troubling Questions and Beyond-Naive Answers

Troubling Questions and Beyond-naive answers H. S. Mukunda, IISc, Bangalore, July 2012 1. Troubling questions? 2. The beginning of “God” in one’s life; defining God? 3. Being contented is good? Being ambitious in life bad? 4. Is science below spirituality? Is spirituality beyond science? 5. Is the state of Sanyāsa great? Is the state of Avadhūta better? 6. Freedom and anonymity 7. Conscious and unconscious parts of the mind 8. 20 minute meditation and other life afterwards? 9. How long to meditate? 10. Can practice of Music lead to Nirvana? 11. Vedic chāntings, alternate to music? Japā an alternate route? 12. Yagnas and burning firewood – clean combustion? 13. Living on beliefs – for how long? 14. Fate or freewill? 15. Great books needed? Watchful passage not adequate? 16. Great men – who and why? 17. Bibiography Preface Traditional upbringing that I came through has had its positive points – devotion to scholastics and being respectful of the scriptures that led me to trust broad understanding that filtered into me from various sources till I was 21. Upsetting of several thoughts took place with Sri. Poornananda tirtha swami who gave lectures on Vedānta, Bhagavadgita and Yoga Vāsishța over several years at Bangalore between 1965 – 1969. His more-than incisive statements led to intensive discussion amongst colleagues and self-examination of the truth of scriptural writings. Professional demands over the next thirty-four years led to setting aside the intensity of pursuit to seek answers to the questions. Tradition held its sway over the mind – issues of miracles, their authenticity, and their importance to life were not dismissed easily. -

The Cloud of Unknowing Pdf Free Download

THE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anonymous | 138 pages | 20 May 2011 | Aziloth Books | 9781908388131 | English | Rookhope, United Kingdom The Cloud of Unknowing PDF Book He writes in Chapter But again, in this very failure of understanding, in the Dionysian formula, we know by unknowing. A similar image is used in the Cloud line and Book Three, poem 9, of Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy, where the First Mover calls back the souls scattered throughout the universe "like leaping flames" trans. In the end, as The Cloud's author insists: " If you want to find your soul, look at what your love"--and, I would add, at who loves you! Nought occurs also in Chapter Eighteen, lines , as a term derogatorily applied to contemplation by those who do not understand it; and, in Chapter Forty-four, by recommending to the contemplative a sorrow connected with the fact that he simply exists or is line , the author evokes a deeply ontological variation of this "nothing" that suggests the longing of contingency for absolute being. Perhaps my favorite thing about this book, however, is the anonymous writer. The analysis of tempered sensuality, motivated by reflections on the resurrection and ascension, is the author's last treatment of the powers of the soul, knowledge of which keeps the contemplative from being deceived in his effort to understand spiritual language and experience lines In the first mansion of the Temple of God which is the soul, understanding and affectivity operate naturally in the natural sphere, although helped by illuminating grace. Whether we prefer Ignatius' way of images or the image-less way of The Cloud, all prayer is a simple reaching out to God what The Cloud calls ' a naked intent for God' and allowing God to reach back to us. -

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary Education

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary Education DRAMA 0411/11/T/PRE Paper 1 Set Text May/June 2014 PRE-RELEASE MATERIAL To be given to candidates on receipt by the Centre. *0371047478* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST The questions in Paper 1 will be based on the three stimuli and on the extract from Yevgheny Shvarts’s play The Naked King provided in this booklet. You may do any preparatory work that is considered appropriate. It is recommended that you perform the extract, at least informally. You will not be permitted to take this copy of the text or any other notes or preparation into the examination. A clean copy of the text will be provided with the Question Paper. This document consists of 31 printed pages and 1 blank page. DC (RCL (JDA)) 79802/2 © UCLES 2014 [Turn over 2 STIMULI You are required to produce a short piece of drama on each stimulus in preparation for your written examination. Questions will be asked on each of the stimuli and will cover both practical and theoretical issues. 1 A death-defying ride 2 Women and children first! 3 Top of the league © UCLES 2014 0411/11/T/PRE/M/J/14 3 EXTRACT Taken from The Naked King by Yevgheny Shvarts These notes are intended to help you understand the context of the drama. Yevgheny Shvarts’s play The Naked King was written in 1934 and is in two Acts. The extract is taken from Act Two and there are five scenes. The plot of Shvarts’s play is based loosely on three fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen: The Swineherd, The Princess and the Pea and The Emperor’s New Clothes. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita