Α. Μ. Klein's Forgotten Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deacon As Wise Fool: a Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate

ATR/100.4 The Deacon as Wise Fool: A Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate Kevin J. McGrane* Deacons often sit with the hurt and marginalized. It is in keeping with our ordination vows as deacons in the Episcopal Church, which say, “God now calls you to a special ministry of servanthood. You are to serve all people, particularly the poor, the weak, the sick, and the lonely.”1 Ever task focused, deacons look for the tangible and concrete things we can do to respond to the needs of the least of Jesus’ broth- ers and sisters (Matt. 25:40). But once the food is served, the money given, the medicine dispensed, then what? The material needs are supplied, but the hurt and the trauma are still very much present. What kind of pastoral care can deacons bring that will respond to the needs of the hurting and traumatized? I suggest that, if we as deacons are going to be sources of contin- ued pastoral care beyond being simple providers of material needs, we need to look to the pastoral model of the wise fool for guidance. With some exceptions here and there, deacons are uniquely fit to practice the pastoral persona of the wise fool. The wise fool is a clinical pastoral persona most identified and de- veloped by the pastoral theologians Alastair V. Campbell and Donald Capps. The fool is an archetype in human culture that both Campbell and Capps view as someone capable of rendering pastoral care. In his essay “The Wise Fool,”2 Campbell describes the fool as a “necessary figure” to counterpoint human arrogance, pomposity, and despo- tism: “His unruly behavior questions the limits of order; his ‘crazy’ outspoken talk probes the meaning of ‘common sense’; his uncon- ventional appearance exposes the pride and vanity of those around * Kevin J. -

Educator Guide: Fashion Statement

Table Of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Key Message 3. Class Activities 4. Glossary of Terms 6. Resources Introduction Every day, millions of people self-identify (or are identified by others) by what they wear. Clothes may indicate one’s profession, religion, or socio-economic status. Whether you intend it or not, your clothes telegraph—to those who know how to read the language—the groups to which you belong (or want to belong). A new original exhibit at the Jewish Museum of Maryland (JMM) will invite students to think more deeply about the messages (overt and ambiguous) embedded in articles of clothing from the last two centuries in the collection of the JMM, and what they can teach us about our own lives. Before you visit, please: • Read through these materials, • Discuss the key message with your students, • Review the glossary of terms that students may find in the exhibit. Jewish Museum of Maryland Educator’s Guide— Page 1 Key Message Fashion Statement will ask students to consider how a man’s black hat can signal religious expression or a fur coat can communicate a woman’s aspirations. Students will consider everyday clothing from club jackets to political tee shirts, military and civilian uniforms to “must-have” accessories, and explore how those everyday objects amplify (and sometimes disguise) identity and affiliation. Using the disciplines of history and material culture studies, Fashion Statement displays clothing and accessories worn by Jewish Marylanders – women, men, and children – in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Historic photographs, documents, and maps will provide context, along with interpretive panels telling the stories of each garment and accessory. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

מכירה מס' 28 יום רביעי י'ז שבט התש"פ 12/02/2020

מכירה מס' 28 יום רביעי י'ז שבט התש"פ 12/02/2020 1 2 בס"ד מכירה מס' 28 יודאיקה. כתבי יד. ספרי קודש. מכתבים. מכתבי רבנים חפצי יודאיקה. אמנות. פרטי ארץ ישראל. כרזות וניירת תתקיים אי"ה ביום רביעי י"ז בשבט התש"פ 12.02.2020, בשעה 19:00 המכירה והתצוגה המקדימה תתקיים במשרדנו החדשים ברחוב הרב אברהם יצחק הכהן קוק 10 בני ברק בימים: א-ג 09-11/12/2020 בין השעות 14:00-20:00 נשמח לראותכם ניתן לראות תמונות נוספות באתר מורשת www.moreshet-auctions.com טל: 03-9050090 פקס: 03-9050093 [email protected] אסף: 054-3053055 ניסים: 052-8861994 ניתן להשתתף בזמן המכירה אונליין דרך אתר בידספיריט )ההרשמה מראש חובה( https://moreshet.bidspirit.com 3 בס"ד שבט התש״פ אל החברים היקרים והאהובים בשבח והודיה לה' יתברך על כל הטוב אשר גמלנו, הננו מתכבדים להציג בפניכם את קטלוג מכירה מס' 28. בקטלוג שלפניכם ספרי חסידות מהדורת ראשונות. מכתבים נדירים מגדולי ישראל ופריטים חשובים מאוספים פרטיים: חתימת ידו של רבי אליעזר פאפו בעל הפלא יועץ זי"ע: ספר דרכי נועם עם קונטרס מלחמת מצווה מהדורה ראשונה - ונציה תנ"ז | 1697 עם חתימות נוספות והגהות חשובות )פריט מס' 160(. פריט היסטורי מיוחד: כתב שליחות )שד"רות( בחתימת המהרי"ט אלגאזי ורבני בית דינו )פריט מס' 216(. ש"ס שלם העותק של בעל ה'מקור ברוך' מסערט ויז'ניץ זצ"ל עם הערות בכתב ידו )פריט מס' 166(. תגלית: כאלף דפים של כתב היד החלק האבוד מתוך חיבורו על הרמב"ם של הגאון רבי יהודה היילברון זצ"ל )פריט מס' 194(. נדיר! כתב יד סידור גדול במיוחד עם נוסחאות והלכות נדירות - תימן תחילת המאה ה17- לערך )פריט מס' 198(. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES English Department Hasidic Judaism in American Literature by Eva van Loenen Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF YOUR HUMANITIES English Department Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy HASIDIC JUDAISM IN AMERICAN LITERATURE Eva Maria van Loenen This thesis brings together literary texts that portray Hasidic Judaism in Jewish-American literature, predominantly of the 20th and 21st centuries. Although other scholars may have studied Rabbi Nachman, I.B. Singer, Chaim Potok and Pearl Abraham individually, no one has combined their works and examined the depiction of Hasidism through the codes and conventions of different literary genres. Additionally, my research on Judy Brown and Frieda Vizel raises urgent questions about the gendered foundations of Hasidism that are largely elided in the earlier texts. -

Confronting the Rise in Anti-Semitic Domestic Terrorism

CONFRONTING THE RISE IN ANTI-SEMITIC DOMESTIC TERRORISM HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERTERRORISM OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 15, 2020 Serial No. 116–58 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 41–310 PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Mar 15 2010 09:11 Sep 22, 2020 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\116TH\20IC0115\41310.TXT HEATH Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi, Chairman SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MIKE ROGERS, Alabama JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island PETER T. KING, New York CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DONALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey JOHN KATKO, New York KATHLEEN M. RICE, New York MARK WALKER, North Carolina J. LUIS CORREA, California CLAY HIGGINS, Louisiana XOCHITL TORRES SMALL, New Mexico DEBBIE LESKO, Arizona MAX ROSE, New York MARK GREEN, Tennessee LAUREN UNDERWOOD, Illinois VAN TAYLOR, Texas ELISSA SLOTKIN, Michigan JOHN JOYCE, Pennsylvania EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri DAN CRENSHAW, Texas AL GREEN, Texas MICHAEL GUEST, Mississippi YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York DAN BISHOP, North Carolina DINA TITUS, Nevada BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey NANETTE DIAZ BARRAGA´ N, California VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida HOPE GOINS, Staff Director CHRIS VIESON, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERTERRORISM MAX ROSE, New York, Chairman SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MARK WALKER, North Carolina, Ranking JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island Member ELISSA SLOTKIN, Michigan PETER T. KING, New York BENNIE G. -

Class Clown and Court Jester: a Case Study Approach to the Tradition of the Fool

CLASS CLOWN AND COURT JESTER: A CASE STUDY APPROACH TO THE TRADITION OF THE FOOL By DAVID CHEVREAU B.A., York University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Counselling Psychology We accept this Thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1994 © David Chevreau, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of (jOO^fr^fr ^SfObL^y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date Apm- ^ 1*T^ DE-6 (2/88) -ii- ABSTRACT Though he is well known, the Class Clown is not particularly well understood. With the exception of one quantitative study by Damingo and Purkey (1978), no significant research has been written on this witty character. The educational community has viewed the Class Clown by and large as an under-achieving student who, in his efforts to get attention, is a disruptive force in the classroom. As such, his behaviour, though often enormously funny, is a threat to the conformity and stability that good classroom discipline demands. -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures). -

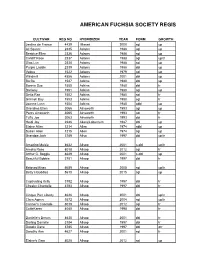

Regn Lst 1948 to 2020.Xls

AMERICAN FUCHSIA SOCIETY REGISTERED FUCHSIAS, 1948 - 2020 CULTIVAR REG NO HYBRIDIZER YEAR FORM GROWTH Jardins de France 4439 Massé 2000 sgl up All Square 2335 Adams 1988 sgl up Beatrice Ellen 2336 Adams 1988 sgl up Cardiff Rose 2337 Adams 1988 sgl up/tr Glas Lyn 2338 Adams 1988 sgl up Purple Laddie 2339 Adams 1988 dbl up Velma 1522 Adams 1979 sgl up Windmill 4556 Adams 2001 dbl up Bo Bo 1587 Adkins 1980 dbl up Bonnie Sue 1550 Adkins 1980 dbl tr Dariway 1551 Adkins 1980 sgl up Delta Rae 1552 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Grinnell Bay 1553 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Joanne Lynn 1554 Adkins 1980 sdbl up Grandma Ellen 3066 Ainsworth 1993 sgl up Percy Ainsworth 3065 Ainsworth 1993 sgl tr Tufty Joe 3063 Ainsworth 1993 dbl tr Heidi Joy 2246 Akers/Laburnum 1987 dbl up Elaine Allen 1214 Allen 1974 sdbl up Susan Allen 1215 Allen 1974 sgl up Grandpa Jack 3789 Allso 1997 dbl up/tr Amazing Maisie 4632 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up/tr Amelia Rose 8018 Allsop 2012 sgl tr Arthur C. Boggis 4629 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up Beautiful Bobbie 3781 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Beloved Brian 5689 Allsop 2005 sgl up/tr Betty’s Buddies 8610 Allsop 2015 sgl up Captivating Kelly 3782 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cheeky Chantelle 3783 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cinque Port Liberty 4626 Allsop 2001 dbl up/tr Clara Agnes 5572 Allsop 2004 sgl up/tr Conner's Cascade 8019 Allsop 2012 sgl tr CutieKaren 4040 Allsop 1998 dbl tr Danielle’s Dream 4630 Allsop 2001 dbl tr Darling Danielle 3784 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Doodie Dane 3785 Allsop 1997 dbl gtr Dorothy Ann 4627 Allsop 2001 sgl tr Elaine's Gem 8020 Allsop 2012 sgl up Generous Jean 4813 -

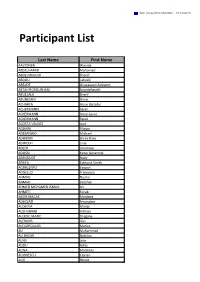

Participant List

Ref. Ares(2015)5922007 - 17/12/2015 Participant List Last Name First Name AALTONEN Wanida ABDELHAMID Mohamed ABDELMEGUID Sheref ABDOU Lahadji ABEJIDE Oluwaseun Adeyemi ABTAHIFOROUSHANI Seyedehasieh ABUELALA Sherif ABUNEMEH Omar ACHARYA Arjun Bahadur ACHERMANN Sarah ACKERMANN Anne-Laure ACKERMANN Raoul ACOSTA VALDEZ Jose ADDARII Filippo ADESANWO Michael ADHIKARI Shree Ram ADINOLFI Livia ADLER Jéromine ADOSSI Yawo Nevemde AERNOUDT Rudy AFRIFA Edmund Smith AGBALENYO Yawovi AGNELLO Francesca AHMAD Najma AHMAD Zeeshan AHMED MOHAMED ISMAIL Ali AHMETI Korab AKSIN MACAK Marijana ALBIZZATI Amandine ALCHEVA Marija ALDHUBAIBI Hitham ALEKSIC MATIC Dragana ALEXAKIS Ilias ALEXOPOULOS Marios ALI Muhammad ALI BACAR Nabilou ALIAS Jose ALIDU Adilu ALINA Marinoiu ALIONESCU Ciprian ALIX Nicole ALLET Marion ALMAZYAN Lida ALMEIDA Katia ALONSO Beatriz ALSAWALAH Abedallah ALTINOK Salih ALVARADO TANAMACHI Sayuri ALVAREZ Ana ALVES Filipe AMADIO Nicolas AMALFITANO Marie AMAZIT Anaïs AMBROSIO Giuseppe AMET Suzon AMITSIS Gabriel ANASTOPOULOS Konstantinos ANCA Gunta ANCEL Florian ANDRES Rodolphe ANDREU Tomás ANDREW Mwebaza ANDRICOPOULOU Anna ANDRIOT Patricia ANDRITSOU Anastasia ANESE Tobia ANGELOVA Milena ANNE Leautier ANSELM Cecile APOLLONI Guglielmo APOSTOLIDIS Catherine APPEL Ulrik ARNOLD David AROYAN Luciné ARREGUI Karin Arriaga Sierra Hermes ARROYO DE SANDE Carmen ARVANITI Chrysafo ASCHARI-LINCOLN Jessica ASLAN Ayse ASRAF Adeeba ASSABA Inès ATAMAN SCHARNING Ayşegül ATAYI Ayoko Veronique ATHANASIADOU Natasha Marie AUCONIE Sophie AUGER Christophe AVENTAGGIATO Giovanni -

Till Eulenspiegel As a “Recurring Character” in the Works of Hans Sachs

Narrative Arrangement in 16th-Century Till Eulenspiegel Texts: The Reinvention of Familiar Structures A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Isaac Smith Schendel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Dr. Anatoly Liberman June 2018 © Isaac Smith Schendel 2018 i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. Anatoly Liberman, for his kind direction, ideas, and guidance through the entire process of graduate school, from the first lectures on Middle High German grammar and Scandinavian Literature, to the preliminary exams, prospectus and multiple thesis drafts. Without his watchful eye, advice, and inexhaustible patience, this dissertation would have never seen the light of day. Drs. James A. Parente, Andrew Scheil, and Ray Wakefield also deserve thanks for their willingness to serve on the committee. Special gratitude goes to Dr. Parente for reading suggestions and leadership during the latter part of my graduate school career. His practical approach, willingness to meet with me on multiple occasions, and ability to explain the intricacies of the university system are deeply appreciated. I have also been helped by a number of scholars outside of Minnesota. The material discussed in the second chapter of the dissertation is a reformulated, expanded, and improved version of my article appearing in Daphnis 43.2. Although the central thesis is now radically different, I would still like to thank Drs. Ulrich Seelbach and Alexander Schwarz for their editorial work during that time, especially as they directed my attention to additional information and material within the S1515 chapbook. -

Project Summer Read 2020

Project SUMMER Read 2020 SUMMER READING SUGGESTIONS AND RESOURCES SUGERENCIAS DE LECTURE VERANO Y RECURSOS Elementary K-5 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read Parent Resources Recursos Para Padres Choosing Books for Children by Betsy Hearne Best of the Best for Children by Denise Perry Donavin, ed. The New Read‐Aloud Handbook by Jim Trelease For Reading Out Loud by Margaret May Kimmel Read to Me: Raising Kids Who Love to Read by Bernice E. Cullinan Parent’s Guide to the Best Books for Children by Eden Ross Lipson Reading Magic by Mem Fox Other Websites Otros sitios web White Plains Public Schools whiteplainspublicschools.org Westchester Libraries Online westchesterlibraries.org White Plains Public Library whiteplainslibrary.org White Plains Youth Bureau whiteplainsyouthbureau.org Barnes & Noble Booksellers barnesandnoble.com Common Sense Media commonsensemedia.org 2020 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read WHITE PLAINS PUBLIC SCHOOLS EDUCATION HOUSE FIVE HOMESIDE LANE WHITE PLAINS, NEW YORK 10605 914-422-2000 www.wpcsd.k12.ny.us Joseph L. Ricca, Ed.D. Superintendent of Schools June 2020 Dear Parent/Guardian, Many parents ask: “What can I do to help my child be a better student?” The key to a good education is reading with understanding. If you encourage your child to read, if you read to your child, if you discuss with your child what is being read, your child will develop a love for reading and learning. Reading is both fun and useful. Folktales, sports news, fashion news, business news, celebrity gossip, and comics –it all has value. Our Project Summer Read program is designed to make it easier to select books, for a full summer of reading.