Greater Dandenong's Culture 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A: Existing Policy Context

City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge Management Plan | APPENDIX A: EXISTING POLICY CONTEXT APPENDIX A: EXISTING POLICY CONTEXT City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge Management Plan | APPENDIX A: EXISTING POLICY CONTEXT . Protecting important productive agricultural areas such as Werribee GREATER DANDENONG PLANNING South, the Maribyrnong River flats, the Yarra Valley, Westernport SCHEME and the Mornington Peninsula. Protect areas of environmental, landscape and scenic value. The Greater Dandenong Planning Scheme provides the high level strategic context within which the Green Wedge Management Plan needs to be . Protect significant resources of stone, sand and other mineral considered. resources for extraction purposes. STATE PLANNING POLICY FRAMEWORK (SPPF) ENVIRONMENTAL AND LANDSCAPE VALUES Clause 12.04‐2 Landscapes includes the strategy to: The SPPF (contained in clauses 11 to 19 of the Greater Dandenong Planning Scheme) sets out statewide planning policy. The most relevant policies . Improve the landscape qualities, open space linkages and include those contained in the ‘Settlement’, ‘Environmental and Landscape environmental performance in Green Wedges and conservation areas Values’ and ‘Economic Development’. and non‐urban areas. SETTLEMENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Clause 11.04‐6 Green Wedges. This policy aims to protect Green Wedges Clause 17.02‐3 State significant industrial land lists a few industrial areas of Metropolitan Melbourne from inappropriate development. Strategies to of state significance including Dandenong South. achieve this are: . Ensure strategic planning and land management of each Green Wedge area to promote and encourage its key features and related values. Support development in the Green Wedge that provides for environmental, economic and social benefits. Consolidate new residential development within existing settlements and in locations where planned services are available and Green Wedge area values can be protected. -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria

SURVEY OF POST-WAR BUILT HERITAGE IN VICTORIA STAGE TWO: Assessment of Community & Administrative Facilities Funeral Parlours, Kindergartens, Exhibition Building, Masonic Centre, Municipal Libraries and Council Offices prepared for HERITAGE VICTORIA 31 May 2010 P O B o x 8 0 1 9 C r o y d o n 3 1 3 6 w w w . b u i l t h e r i t a g e . c o m . a u p h o n e 9 0 1 8 9 3 1 1 group CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 7 1.2 Project Methodology 8 1.3 Study Team 10 1.4 Acknowledgements 10 2.0 HISTORICAL & ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXTS 2.1 Funeral Parlours 11 2.2 Kindergartens 15 2.3 Municipal Libraries 19 2.4 Council Offices 22 3.0 INDIVIDUAL CITATIONS 001 Cemetery & Burial Sites 008 Morgue/Mortuary 27 002 Community Facilities 010 Childcare Facility 35 015 Exhibition Building 55 021 Masonic Hall 59 026 Library 63 769 Hall – Club/Social 83 008 Administration 164 Council Chambers 85 APPENDIX Biographical Data on Architects & Firms 131 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O 3 4 S U R V E Y O F P O S T - W A R B U I L T H E R I T A G E I N V I C T O R I A : S T A G E T W O group EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this survey was to consider 27 places previously identified in the Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria, completed by Heritage Alliance in 2008, and to undertake further research, fieldwork and assessment to establish which of these places were worthy of inclusion on the Victorian Heritage Register. -

Frankston Planning Scheme Municipal Strategic Statement

FRANKSTON PLANNING SCHEME 21 MUNICIPAL STRATEGIC STATEMENT 19/01/2006 VC37 21.01 Municipal Profile 19/01/2006 VC37 21.01-1 Introduction 19/01/2006 VC37 Frankston City is situated on the eastern shore of Port Phillip approximately 42 kilometres south of Melbourne. The City covers an area of approximately 131 square kilometres from Seaford Wetlands in the north to Mount Eliza in the south and east to the Western Port Highway. The western boundary of the City consists of approximately 9.5 kilometres of Port Phillip coastline. (Refer to the Context and Regional Influence Map.) Frankston City Council was created by Order of the Governor in Council on 15 December 1994. The Council area consists of the former City of Frankston (less the Mt Eliza and Baxter District), the Carrum Downs District of the former City of Springvale and the Carrum Downs, Langwarrin and Skye Districts of the former City of Cranbourne. These districts and their communities combine to create a City of considerable physical, social, economic and cultural diversity. Frankston City is a place which, for various reasons, is perceived by people in many different ways. Michael Jones in his book “Frankston Resort to City” (1989) outlines the paradox of Frankston which is still applicable to our new City: “The township, established in 1854, has never quite been able to decide whether it is a country town servicing its hinterland, a pleasure resort, a dormitory suburb for Melbourne, the gateway to the Mornington Peninsula or a self-contained City with its own employment and retail centres.” (p19;1989) The City, through the leadership of its Council, has the responsibility for establishing, guiding and managing the development of Frankston City to establish a clear sense of place and identity. -

The Spirit of Enterprise

THE SPIRIT OF ENTERPRISE 1. Context The City of Greater Dandenong is the capital of Melbourne’s south-east. Located approximately 35km from Melbourne CBD, the city spreads over 129 square kilometres, ans has a population of 160 000 inhabitants. The City of Greater Dandenong is home to more than 150 different nationalities, as well as 2 000 asylum seekers. More than half of its inhabitants were born overseas, and more than 70per cent speak a language other than English (Vietnamese, Khmer, Chinese, Greek, Punjabi, Sinhalese, etc.), making it Australia’s most culturally diverse community. 1 Greater Dandenong is located on a territory nested in the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges, an area which was inhabited for tens of thousands of years by the Wurundjeri and Boonerwrung (Bunurong) tribes of the Kulin Nation. Today, it is a progressive, culturally diverse place to live, work and visit, with a vibrant economy in both retail and manufacturing sectors, and some of Victoria’s most culturally exciting places. 2. Dandenong and culture The City of Greater Dandenong has a rich and diverse history, reflected in its historical sites and through its Indigenous and migrant history. Springvale plays an important role in the context of that landscape, recognised as an important shopping place between Melbourne CBD and Dandenong.It is home to the largest and most established south-east Asian cultural precinct in Greater Dandenong. Springvale was named in the early 1850s due to its abundance of natural springs. Springvale waschosen as a location for one of the Commonwealth Government’s purpose-built Migrant Hostels, known as the Enterprise. -

21 Municipal Strategic Statement 21.01 Municipal

LOCAL PROVISION GREATER DANDENONG PLANNING SCHEME 21 MUNICIPAL STRATEGIC STATEMENT 21.01 MUNICIPAL PROFILE 21.01-1 Overview The City of Greater Dandenong acknowledges the Kulin Nation people as the traditional custodians of land on which the City is located. The City of Greater Dandenong was established on 15 December 1994 by the merger of the former City of Dandenong, approximately seventy percent of the former City of Springvale and small parts of the former Cities of Berwick and Cranbourne. The City occupies 129.6 square kilometres and its centre is approximately thirty kilometres east of the Melbourne Central Activities District (CAD). It includes the suburbs of Dandenong, Dandenong North, Dandenong South, Springvale, Springvale South, Noble Park, Keysborough, Lyndhurst and Bangholme. The population is rapidly ageing and was estimated at 130,941 in 1997, with a projected decline to 128,028 in 2011. Fourteen percent of families are sole-parent. Greater Dandenong has an extremely culturally diverse population with 137 different nationalities represented, of which forty-six percent were born overseas. Thirty-eight percent are from non-English speaking backgrounds. The most significant ethnic grouping is the Asian-born population, which is one of the highest concentrations in metropolitan Melbourne. Migration patterns reflect areas of global conflict and world “hot spots”. Incomes in Greater Dandenong are characteristically low compared with metropolitan Melbourne. Unemployment has traditionally exceeded regional and State levels by three to four percent although there has been a decline in unemployment rates in recent years. The labour force is relatively low skilled, with sixty-seven percent of the population without tertiary qualifications. -

SCG Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation

Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation September 2019 spence-consulting.com Spence Consulting 2 Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation Analysis by Gavin Mahoney, September 2019 It’s been over 20 years since the historic Victorian Council amalgamations that saw the sacking of 1600 elected Councillors, the elimination of 210 Councils and the creation of 78 new Councils through an amalgamation process with each new entity being governed by State appointed Commissioners. The Borough of Queenscliffe went through the process unchanged and the Rural City of Benalla and the Shire of Mansfield after initially being amalgamated into the Shire of Delatite came into existence in 2002. A new City of Sunbury was proposed to be created from part of the City of Hume after the 2016 Council elections, but this was abandoned by the Victorian Government in October 2015. The amalgamation process and in particular the sacking of a democratically elected Council was referred to by some as revolutionary whilst regarded as a massacre by others. On the sacking of the Melbourne City Council, Cr Tim Costello, Mayor of St Kilda in 1993 said “ I personally think it’s a drastic and savage thing to sack a democratically elected Council. Before any such move is undertaken, there should be questions asked of what the real point of sacking them is”. Whilst Cr Liana Thompson Mayor of Port Melbourne at the time logically observed that “As an immutable principle, local government should be democratic like other forms of government and, therefore the State Government should not be able to dismiss any local Council without a ratepayers’ referendum. -

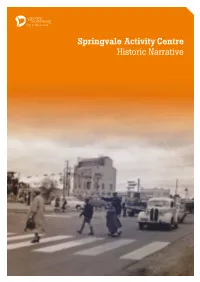

Springvale Activity Centre Historic Narrative Introduction

Springvale Activity Centre Historic Narrative Introduction > The area in which Greater Dandenong is now Greater Dandenong’s three activity centres; located is the territory of the Wurundjeri and Dandenong, Springvale and Noble Park, have evolved Boonwurrung (or Bunurong) tribes of the Kulin since 1852. Upon the township of Dandenong being Nation and has been for tens of thousands of laid it soon became a trading centre for farmers and years.The availability and occurrence of water graziers establishing it as ‘The Market Town’ with a most infl uenced living patterns in prehistory and livestock produce and goods market started in 1866. concentrations of Indigenous people occurred By 1873 the Shire of Dandenong was a large region around the former Carrum Swamp, the fl oodplain, that covered the areas of Springvale and Noble Park wetlands and elevated areas along Dandenong as well as Dandenong. Creek. Cultural, ceremonial and spiritual life was The rapid growth of the region and the pressure to dictated by the seasons through the availability of provide urban services, particularly after World War sustainable natural resources and closely observed II, resulted in the formation of two cities; when in changes in plant growth and animal behaviour. 1955 Springvale and Noble Park Shire was created Aboriginal living patterns were severely by severance from Dandenong Shire. Dandenong was disrupted when European settlers arrived in the proclaimed a City in 1959 and Springvale (including Port Phillip region. The Aboriginal population Noble Park) followed in 1961. Each city developed a declined by 80 per cent in the period from 1834 unique character in response to local conditions. -

Gipps-Land Gate

Gipps-Land Gate Dandenong & District Historical Society Headquarters and Resource Centre: Houlahan Community Centre 186 Foster Street East, Dandenong - P.O. Box 8029, Dandenong 3175 Ph. 03 9794 8967 Email addresses [email protected] + [email protected] Website: ddhs.com.au Life Members Muriel Norris, Jenny Ferguson, Ray Carter, Carmen Powell Chief Sponsor Our society acknowledges with thanks the assistance of The City of Greater Dandenong in allowing us the use of the Houlahan Community Centre, and for their continuing monetary assistance. Sponsor A special thank you to our loyal sponsor The Dandenong Club Contacts Note: Please leave a message on our answering machine and we will endeavour to get back to you within the week. Ph:9794 8967 Our rooms are open Wednesdays 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. President Chris Keys Vice President Chris Ware Secretary Jenny Ferguson Treasurer Ken Masters Magazine Editor Carmen Powell ph: 9796 2456 Written contributions are always welcome! Gipps-Land Gate Gipps-Land Gate Twice-yearly Journal of the Dandenong & District Historical Society Vol. 43 No.1 $5 April 2016 ISSN 1321-5035 Obituary: Volunteer Janice Asher History of floods in Dandenong. The Carrum Swamp south-west of Dandenong By Ray Carter The Dandenong Creek at Dandenong By Ray Carter Other flooding in Dandenong By Ray Carter Retarding basins and flood plains. By Ray Carter We miss you Jan. The 1934 floods By Ray Carter Drownings in the Dandenong Creek By Ray Carter Dandenong Panoramic Drive-in Theatre [Lunar Dandenong] By Ray Carter Gipps-Land Gate Usually, volunteer Jan Asher rang first thing Wednesday mornings if she was unable to come in to the Society's research rooms. -

Government Emblems, Embodied Discourse and Ideology: an Artefact-Led History of Governance in Victoria, Australia

Government Emblems, Embodied Discourse and Ideology: An Artefact-led History of Governance in Victoria, Australia Katherine Hepworth Doctor of Philosophy 2012 ii iii Abstract Government emblems are a rich source of historical information. This thesis examines the evidence of past governance discourses embodied in government emblems. Embodied discourses are found within an archive of 282 emblems used by local governments in Victoria, Australia in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They form the basis of a history of governance in the State of Victoria from first British exploration in 1803 to the present day. This history of governance was written to test the main contribution of this thesis: a new graphic design history method called discursive method. This new method facilitates collecting an archive of artefacts, identifying discourses embodied within those artefacts, and forming a historical narrative of broader societal discourses and ideologies surrounding their use. A strength of discursive method, relative to other design history methods, is that it allows the historian to seriously investigate how artefacts relate to the power networks in which they are enmeshed. Discursive method can theoretically be applied to any artefacts, although government emblems were chosen for this study precisely because they are difficult to study, and rarely studied, within existing methodological frameworks. This thesis demonstrates that even the least glamorous of graphic design history artefacts can be the source of compelling historical narratives. iv Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been written without the support of many people. Fellow students, other friends and extended family have helped in many small ways for which I am so grateful. -

Local Government (Validation) Act 1988 No

Local Government (Validation) Act 1988 No. 71 of 1988 TABLE OF PROVISIONS Section 1. Purpose. 2. Commencement. 3. Validation of Orders in Council. 4. Shire of Kyneton. 5. Shire of Colac and Dimboola. 6. Review of internal boundaries. THE SCHEDULE 1177 Victoria No. 71 of 1988 Local Government (Validation) Act 1988 [Assented to 15 December 1988] The Parliament of Victoria enacts as follows: Purpose. 1. The purpose of this Act is to validate certain Orders made under Part II of the Local Government Act 1958 and for certain other purposes. Commencement. 2. This Act comes into operation on the day on which it receives the Royal Assent. Validation of Orders in Council. 3. (1) An Order made by the Governor in Council under Part II of the Local Government Act 1958 in relation to a municipality referred to in column 1 of an item in the Schedule and published in the Government Gazette on the date referred to in column 3 of that item shall be deemed to have taken effect in accordance with that Part on the date referred to in column 4 of that item and thereafter always to have been valid. 1179. s. 4 Local Government (Validation) Act 1988 (2) Any election for councillors of a municipality referred to in an item in the Schedule, and any thing done by or in relation to that municipality or its Council or persons acting as its councillors or otherwise affecting that municipality, on or after the date on which the Order referred to in that item took effect shall be deemed to have been as validly held or done as it would have been if sub-section (1) had been in force on that date. -

Environmental Audit Reports

INFORMATION REGARDING ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT REPORTS August 2007 VICTORIA'S AUDIT SYSTEM AUDIT REPORT CURRENCY An environmental audit system has operated in Audit reports are based on the conditions encountered Victoria since 1989. The Environmenf Profecfion Acf and information reviewed at the time of preparation 1970 (the Act) provides for the appointment by the and do not represent any changes that may have Environment Protection Authority (EPA Victoria) of occurred since the date of completion. As it is not environmental auditors and the conduct of possible for an audit to present all data that could be independent, high quality and rigorous environmental of interest to all readers, consideration should be audits. made to any appendices or referenced documentation An environmental audit is an assessment of the for further information. condition of the environment, or the nature and extent When information regarding the condition of a site of harm (or risk of harm) posed by an industrial changes from that at the time an audit report is process or activity, waste, substance or noise. issued, or where an administrative or computation Environmental audit reports are prepared by EPA- error is identified, environmental audit reports, appointed environmental auditors who are highly certificates and statements may be withdrawn or qualified and skilled individuals. amended by an environmental auditor. Users are Under the Act, the function of an environmental advised to check EPA's website to ensure the currency auditor is to conduct environmental audits and of the audit document. prepare environmental audit reports. Where an environmental audit is conducted to determine the PDF SEARCHABILITY AND PRINTING condition of a site or its suitability for certain uses, an environmental auditor may issue either a certificate or EPA Victoria can only certify the accuracy and statement of environmental audit. -

Greater Dandenong Council News

FEBRUARY 2021 Greater Dandenong Council News Summer fun PAGE 4 Australia Make Melbourne City Day Awards Your Move Football Club ► PAGE 3 ► PAGE 9 ► PAGE 14 2 Council News Customer Service Centres Dandenong Civic Centre Mayor’s message 225 Lonsdale Street, Dandenong Springvale Community Hub Welcome to the February edition of Greater Dandenong 5 Hillcrest Grove, Springvale Council News. Keysborough Customer Service As the holiday period draws to a close, our children are Shop A7 Parkmore Shopping Centre, returning to school and many of us are returning to work. Keysborough After the events of 2020, I hope that this year brings you all a sense of routine and something that resembles ‘normal’ life. All correspondence to: Many of our programs and services are resuming for the year, Greater Dandenong Council News and we are busy making plans for the future. We have a few PO Box 200 Mayor consultations on at the moment and would love to hear from Cr Angela Long Dandenong VIC 3175 our community on these. Turn to page 6 to find out how to Email: [email protected] have your say on the Disability, Access and Equity Policy. On page 7 we invite feedback on our Urban Forest Strategy, while page 8 talks about your chance to contribute to our Council Plan 2021–25. Phone: 8571 1000 Just before Christmas Council opened its latest open space to the community in the Fax: 8571 5196 heart of Dandenong. Read more about it on page 7. www.greaterdandenong.vic.gov.au We also welcomed the announcement of one of Melbourne’s top soccer clubs moving to the south east.