Inhaled Cadmium Oxide Nanoparticles: Their in Vivo Fate and Effect on Target Organs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparison of Composite Transparent Conducting Oxides Based on the Binary Compounds Cdo and Sno2

October 2001 • NREL/CP-520-31017 A Comparison of Composite Transparent Conducting Oxides Based on the Binary Compounds CdO and SnO2 Preprint X. Li, T. Gessert, C. DeHart, T. Barnes, H. Moutinho, Y. Yan, D. Young, M. Young, J. Perkins, and T. Coutts To be presented at the NCPV Program Review Meeting Lakewood, Colorado 14-17 October 2001 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 NREL is a U.S. Department of Energy Laboratory Operated by Midwest Research Institute • Battelle • Bechtel Contract No. DE-AC36-99-GO10337 NOTICE The submitted manuscript has been offered by an employee of the Midwest Research Institute (MRI), a contractor of the US Government under Contract No. DE-AC36-99GO10337. Accordingly, the US Government and MRI retain a nonexclusive royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or allow others to do so, for US Government purposes. This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. -

The Preparation of Polysiloxanes from Halosilanes

European Patent Office © Publication number: 0 205 066 Office europeen des brevets A2 © EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION © Application number: 86107474.8 © Int. CI.4: C 08 G 77/08 © Date of filing: 02.06.86 © Priority: 14.06.85 US 744708 © Applicant: DOW CORNING CORPORATION P.O. Box 1767 Midland Michigan 48640(US) © Date of publication of application: 17.12.86 Bulletin 86/51 @ Inventor: Marko, Ollie William Route 2 Box 60 © Designated Contracting States: Carrollton Kentucky(US) DE FR GB @ Inventor: Steinmeyer, Robert David 214 Deatherage Drive Carrollton Kentucky(US) © Inventor: Rentsch, Stefan Felix 5800 Siebert Midland Michigan(US) © Representative: Sternagel, Hans-Gunther, Dr. et al, Patentanwalte Dr. Michael Hann Dr. H.-G. Sternagel Sander Aue30 D-5060 Bergisch Gladbach 2(DE) © The preparation of polysiloxanes from halosilanes. ©@ This This invention relates to a process for the preparation of polysiloxanes by reacting halosilanes in the presence of metal oxides and sulfolane. Preferred metal oxides include anti- mony (III) oxide, antimony (V) oxide, cadmium oxide, calcium oxide, copper (II) oxide, indium oxide, iron (II) oxide, iron (III) oxide, magnesium oxide, manganese (II) oxide, mercury (II) oxide, nickel (II) oxide, thallium (III) oxide, tin (II) oxide, and zinc oxide. Improved yields and rates of reaction can be observed with the process of this invention. Croydon Printing Company Ltd. This invention relates to a process for the preparation of polysiloxanes from halosilanes. 14ore specifically, this invention relates to a process for the preparation of polysiloxanes by reacting halosilanes in the presence of metal oxides and sulfolane. Polysiloxanes are most commonly prepared by the hydrolysis of halosilanes. -

Cadmium Oxide Ec Number: 215-146-2 Cas Number: 1306-19-0

SUBSTANCE NAME: CADMIUM OXIDE EC NUMBER: 215-146-2 CAS NUMBER: 1306-19-0 MEMBER STATE COMMITTEE SUPPORT DOCUMENT FOR IDENTIFICATION OF CADMIUM OXIDE AS A SUBSTANCE OF VERY HIGH CONCERN BECAUSE OF ITS CMR 1 PROPERTIES AND BECAUSE OF ITS ADVERSE EFFECTS ON KIDNEY AND BONE TISSUES AFTER PROLONGED EXPOSURE, WHICH CAUSE PROBABLE SERIOUS EFFECTS TO HUMAN HEALTH WHICH GIVE RISE TO AN EQUIVALENT LEVEL OF CONCERN TO THOSE OF CMR AND PBT/vPvB2 SUBSTANCES Adopted on 12 June 2013 1 CMR means carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction 2 PBT means persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic; vPvB means very persistent and very bioaccumulative SVHC SUPPORT DOCUMENT – CADMIUM OXIDE CONTENTS 1 IDENTITY OF THE SUBSTANCE AND PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PROPERTIES................. 9 1.1 Name and other identifiers of the substance ....................................................... 9 1.2 Composition of the substance............................................................................ 9 1.3 Physico-chemical properties .............................................................................. 10 2 HARMONISED CLASSIFICATION AND LABELLING....................................................... 11 3 ENVIRONMENTAL FATE PROPERTIES........................................................................ 12 4 HUMAN HEALTH HAZARD ASSESSMENT ................................................................... 14 4.1 Toxicokinetics (absorption, metabolism, distribution and elimination)..................... 14 4.2 Kidney toxicity ............................................................................................... -

Commission Decision of 10 June 2009 Amending, for the Purposes Of

11.6.2009 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 148/27 COMMISSION DECISION of 10 June 2009 amending, for the purposes of adapting to technical progress, the Annex to Directive 2002/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards exemptions for applications of lead, cadmium and mercury (notified under document number C(2009) 4187) (Text with EEA relevance) (2009/443/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, cadmium-based optocouplers in all professional audio applications should become practicable by 31 December 2009. Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, (7) Substitution for mercury used as a cathode sputtering inhibitor in DC plasma displays with content of up to Having regard to Directive 2002/95/EC of the European 30 mg per display is currently technically impracticable, Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 on the but should be practicable by 1 July 2010. restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in elec trical and electronic equipment ( 1), and in particular Article 5(1)(b) thereof, (8) Directive 2002/95/EC should therefore be amended accordingly. Whereas: (9) Pursuant to Article 5(2) of Directive 2002/95/EC, the Commission has consulted the relevant parties. (1) Directive 2002/95/EC requires the Commission to evaluate certain hazardous substances prohibited pursuant to Article 4(1) of that Directive. (10) The measures provided for in this Decision are in accordance with the opinion of the Committee estab lished by Article 18 of Directive 2006/12/EC of the (2) Certain materials and components containing lead and European Parliament and of the Council ( 2), cadmium should be exempted from the prohibition, since the elimination of these hazardous substances in those specific materials and components is still tech HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: nically or scientifically impracticable. -

Cadmium and Cadmium Compounds

Locating and Estimating Air Emissions From Sources of Cadmium and Cadmium Compounds U. S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air and Radiation Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Locating and Estimating Air Emissions From Sources of Cadmium and Cadmium Compounds Prepared for: Anne Pope Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Technical Support Division U. S. Environmental Protection Agency Research Triangle Park, N.C. 27711 Prepared by: Midwest Research Institute 401 Harrison Oaks Boulevard, Suite 350 Cary, North Carolina 27513 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1 PURPOSE OF DOCUMENT ..................1-1 REFERENCES ....................1-4 2 OVERVIEW OF DOCUMENT CONTENTS .............2-1 3 BACKGROUND.......................3-1 NATURE OF POLLUTANT ................3-1 OVERVIEW OF PRODUCTION, USE, AND EMISSIONS ....3-4 Production..................3-4 Use.....................3-6 Emissions ..................3-6 REFERENCES ................... 3-13 4 EMISSIONS FROM CADMIUM PRODUCTION ...........4-1 CADMIUM REFINING AND CADMIUM OXIDE PRODUCTION ...4-1 Process Description .............4-3 Emissions and Controls ............4-6 CADMIUM PIGMENTS PRODUCTION ........... 4-11 Process Description ............ 4-14 Emissions and Controls ........... 4-19 CADMIUM STABILIZERS PRODUCTION ......... 4-20 Process Description ............ 4-22 Emission and Controls ........... 4-24 OTHER CADMIUM COMPOUND PRODUCTION ........ 4-25 Process Descriptions ............ 4-25 Emissions and Controls ........... 4-29 REFERENCES ................... 4-32 5 -

Chapter 6.3 Cadmium

Chapter 6.3 Cadmium General description Cadmium (Cd) is a soft, ductile, silver-white metal that belongs together with zinc and mercury to group IIb in the Periodic Table. It has relatively low melting (320.9 °C) and boiling (765 °C) points and a relatively high vapour pressure. In the air cadmium is rapidly oxidized into cadmium oxide. However, when reactive gases or vapour such as carbon dioxide, water vapour, sulfur dioxide, sulfur trioxide or hydrogen chloride are present, cadmium vapour reacts to produce cadmium carbonate, hydroxide, sulfite, sulfate or chloride, respectively. These compounds may be formed in chimney stacks and emitted to the environment. Several inorganic cadmium compounds are quite soluble in water e.g. acetate, chloride and sulfate, whereas cadmium oxide, carbonate and sulfide are almost insoluble (1). Sources Cadmium is a relatively rare element (0.2 mg/kg in the earth crust) and is not found in the pure state in the nature. It occurs mainly in association with the sulfide ores of zinc, lead and copper. Cadmium has only been produced commercially in the twentieth century. It is a by- product of the zinc industry; its production is thus determined essentially by that of zinc. Before the First World War cadmium was not usually recovered from zinc plants or other nonferrous metals plants, which resulted in an uncontrolled contamination of the environment for decades. The average annual production of cadmium throughout the world increased from only 20 tonnes in the 1920s to about 12 000 tonnes in the period 1960–1969, 17 000 tonnes in 1970–1984; since 1987 it has fluctuated around 20 000 tonnes (2,3). -

THE MONATOMIC IONS! 1. What Is the Formula for Silver? Ag 2. What Is

Name: ______________________________ THE MONATOMIC IONS! 1. What is the formula for silver? Ag+ 22. What is the formula for cobalt (II)? Co2+ 2. What is the formula for cadmium? Cd2+ 23. What is the formula for chromium (II)? Cr2+ 3. What is the formula for manganese (II)? Mn2+ 24. What is the formula for copper (II)? Cu2+ 4. What is the formula for nickel (II)? Ni2+ 25. What is the formula for tin (IV)? Sn4+ 5. What is the formula for chromous? Cr2+ 26. What is the formula for lead (IV)? Pb4+ 6. What is the formula for zinc? Zn2+ 27. What is the formula for iron (III)? Fe3+ 2+ 2+ 7. What is the formula for cobaltous? Co 28. What is the formula for mercury (I)? Hg2 8. What is the formula for cuprous? Cu+ 29. What is the formula for lead (II)? Pb2+ 9. What is the formula for ferrous? Fe2+ 30. What is the formula for mercury (II)? Hg2+ 2+ 2+ 10. What is the formula for mercurous? Hg2 31. What is the formula for iron (II)? Fe 11. What is the formula for stannous? Sn2+ 32. What is the formula for copper (I)? Cu+ 12. What is the formula for plumbous? Pb2+ 33. What is the formula for tin (II)? Sn2+ 13. What is the formula for chromic? Cr3+ 34. What is the formula for fluoride? F- 14. What is the formula for cobaltic? Co3+ 35. What is the formula for chloride? Cl- 15. What is the formula for cupric? Cu2+ 36. What is the formula for hydride? H- 16. -

The Dissolving Mechanisms of Cadmium and Lead in Nitric Acid

Ind. Health, 1967, 5, 60. THE DISSOLVING MECHANISMS OF CADMIUM AND LEAD IN NITRIC ACID Noboru HARA National Institute of Industrial Health, Kizuki-Sumiyoshi, Kawasaki (Received October 3, 1966) Strong acids are very effective to destroy the organic substances and they dissolve the metallic materials at the same time. The mixed acid of concentrated sulphuric acid and nitric acid or aqua regia is suitable for this purpose, and is used widely. But they are not always effective to dissolve the metallic elements. In this experi- ment, the solubilities of cadmium and lead or their oxides in the nitric acid are determined and the dissolving mechanisms of these two metals are found not to be the same. The solubilities of lead and its oxides have their maximum at some concentration of the acid, but those of cadmium and its oxide have not. In dissolu- tion of metallic substances, therefore, concentration of acid as well as its kind should be considered. The mechanism that metallic substances dissolve in the concentrated nitric acid (more than 1 N) is not similar to that in the diluted acid (pH 1•`7). The author determined the solubilities of cadmium, lead and their oxides in the concentrated nitric acid. PROCEDURE 1. Cadmium and its oxide. Fifty ml of various concentrations of nitric acid are put in 200 ml of Erlenmeyer flasks. The sufficient of metallic cadmium and its oxide are weighed accurately, and are added into these flasks little by little. The dissolving reaction occurs at once. The flasks are cooled by cold water until the violent reactions are over. -

Cadmium Oxide and Hydroxide

300 Cadmium Oxide and Hydroxide COMPONENTS: ORIGINAL MEASUREMENTS: (1) Cadmium hydroxide; Cd(OH)2; [21041-95-2] Rozentsveig, S. A.; Ershler, B. V.; (2) Potassium hydroxide; KOH; [1310-58-3] Shtrum, E. L.; Ostanina, M. M. T4Udy (3) Sodium hydroxide; NaOH; [1310-73-2] Sove-6c.han.i.ya E£.ek:t!tokfWn. Akad. Nauk. (4) Lithium hydroxide; LiOH; [1310-65-2] SSSR, Otde£.. KfWn. Nauk 1950, 571-8. (5) Water; H 0; [7732-18-5] 2 VARIABLES: PREPARED BY: Concentration of the alkali hydroxides. T. P. Dirkse EXPERIMENTAL VALUES: Solubility of Cd(OH)2 in aqueous alkalies -3 Ccimol dm -3 calkalie/mol dm in KOH in NaOH in LiOH --- 6 6 I 9 x 10- 9 x 10- ----- 5 2.5 6 x 10- 5 x 10-5 traces 5 4 -5 4 9 x 10- 10- 4.4 x 10 -4 7 1.2 x 10 1.4 x 10-4 9 x 10-5 -4 4 10 1.5 x 10 1.6 x 10- 1.21 x 10-4 No temperature is specified for these results but the results appear to have been obtained at room temperature. The solubility determinations were incidental to the main purpose of the authors, which was to describe the electrochemical behavior of cadmium in these solutions. AUXILIARY INFORMATION METHOD/APPARATUS/PROCEDURE: SOURCE AND PURITY OF MATERIALS: The only statement about the procedure is No information is given. that the analytical results were determined by a polarographic method. Nothing is stated about the method whereby equilibrium was attained or verified. ESTIMATED ERROR: No information is given. -

Cadmium and Zinc Nitrites. 169

View Article Online / Journal Homepage / Table of Contents for this issue RAY : CADMIUM AND ZINC NITRITES. 169 XV1.-Cadmium and Zinc Nitrites. By PRAFULLACHANDRA RAY. INview of the contradictory statements of the previous workers in this field, it seemed desirable to undertake a fresh investigation of cadmium and zinc nitrites. At the outset it may be pointed out that, so far as the nitrite- forming capacity of mercury and cadmium is concerned, the ques- tion is not one of the basic character of the metal. Mercury,* which occupies the lowest position in group IIB (in the electro- potential series), yields a fairly stable normal nitrite, because both its chloride and nitrite are very feebly dissociated in aqueous solution (RBy and Dhar, T., 1912, 101, 966). Thomsen found that mercuric oxide with its equivalent of aqueous hydrochloric acid evolves 18,920 calories, whereas with its equivalent, of nitric acid it evolves only 6400 calories, and to this difference he ascribes the reason that an aqueous solution of mercuric nitrate is completely converted into chloride by the addition of an aqueous solution of hydrochloric acid. Mercuric chloride in aqueous solution is again completely converted into the cyanide by the addition of hydro- cyanic acid. Cadmium hydroxide also behaves differently towards the ordinary mineral acids. Thus, whilst zinc and magnesium hydroxides with hydrochloric, hydrobromic, and hydriodic acids, respectively, give almost the same value for the heat of neutralisa- tion, namely, about 19,500 calories, with cadmium hydroxide the heat of neutralisation goes on increasing. Thomsen regarded the behaviour of cadmium oxide towards the above acids as exceptional, and on that account he refused to class cadmium hydroxide in the Published on 01 January 1917. -

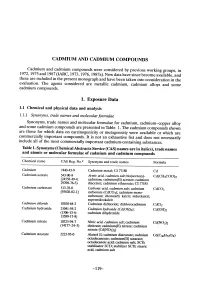

CPY Document

eADMIUM AN eADMIUM COMPOUNDS Cadmium and cadmium compounds were considered by previous working groups, in 1972,1975 and 1987 (lARC, 1973, 1976, 1987a). New data have since become available, and these are included in the present monograph and have been taken into consideration in the evaluation. The agents considered are metallic cadmium, cadmium alloys and sorne cadmium compounds. 1. Exposure Data 1.1 Chemical and physical data and analysis 1.1.1 Synonyms, trade names and molecular formulae Synonyms, trade names and molecular formulae for cadmium, cadmium-copper alloy and some cadmium compounds are presented in Thble 1. The cadmium compounds shown are those for which data on carcinogenicity or mutagenicity were available or which are commercially important compounds. It is not an exhaustive list and does not necessarily include all of the most commercially important cadmium-containing substances. Table 1. Synonyms (Chemical Abstracts Servce (CAS) names are in italics), trade names and atomic or molecular fonnulae of cadmium and cadmium compounds Chemical name CAS Reg. No. a Synonyms and trade names Formula Cadmium 744-43-9 Cadmium metal; CI 77180 Cd Cadmium acetate 543-90-8 Acetic acid, cadmium salt; bis(acetoxy)- Cd(CH3COO)i (24558-49-4; cadmium; cadmium(II) acetate; cadmium 29398-76-3) diacetate; cadmium ethanoate; CI 77185 Cadmium carbnate 513-78-0 Carbomc acid, cadmium salt; cadmium CdC03 (93820-02-1) carbnate (CdC03); cadmium mono- carbnate; chemcarb; kalcit; mikokalcit; supermikokalcit Cadmium ch/oride 10108-64-2 Cadmium dichloride; -

Stable Isotopes of Cadmium Available from ISOFLEX

Stable isotopes of cadmium available from ISOFLEX Isotope Z(p) N(n) Atomic Mass Natural Abundance Enrichment Level Chemical Form Cd-106 48 58 105.90646 1.25% 81.00%-99.00% Metal Cd-106 48 58 105.90646 1.25% 81.00%-99.00% Oxide Cd-108 48 60 107.90418 0.89% 66.00%-99.00% Metal Cd-108 48 60 107.90418 0.89% 66.00%-99.00% Oxide Cd-110 48 62 109.903006 12.49% 95.00%-99.00% Metal Cd-110 48 62 109.903006 12.49% 95.00%-99.00% Oxide Cd-111 48 63 110.904182 12.80% 95.00%-97.50% Metal Cd-111 48 63 110.904182 12.80% 95.00%-97.50% Oxide Cd-112 48 64 111.902758 24.13% 88.00%-98.00% Metal Cd-112 48 64 111.902758 24.13% 88.00%-98.00% Oxide Cd-113 48 65 112.904402 12.22% 93.00%-96.00% Metal Cd-113 48 65 112.904402 12.22% 93.00%-96.00% Oxide Cd-114 48 66 113.903359 28.73% 99.00% Metal Cd-114 48 66 113.903359 28.73% 99.00% Oxide Cd-116 48 68 115.904756 7.49% 99.00% Metal Cd-116 48 68 115.904756 7.49% 99.00% Oxide Cadmium was discovered in 1817 by Friedrich Strohmeyer. Its name originates with the Latin word cadmia (meaning "calamine" or "zinc carbonate") as well as the Greek word kadmeia, with the same meaning. Cadmium is a bluish-white lustrous soft metal with a close-packed hexagonal system.