Caught in the Web Or Lost in the Textbook?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

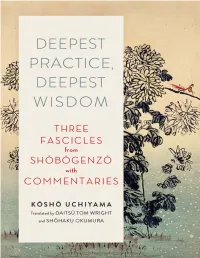

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

THE SUN, the MOON and FIRMAMENT in CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY and on the RELATIONS of CELESTIAL BODIES and SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets

THE SUN, THE MOON AND FIRMAMENT IN CHUKCHI MYTHOLOGY AND ON THE RELATIONS OF CELESTIAL BODIES AND SACRIFICE Ülo Siimets Abstract This article gives a brief overview of the most common Chukchi myths, notions and beliefs related to celestial bodies at the end of the 19th and during the 20th century. The firmament of Chukchi world view is connected with their main source of subsistence – reindeer herding. Chukchis are one of the very few Siberian indigenous people who have preserved their religion. Similarly to many other nations, the peoples of the Far North as well as Chukchis personify the Sun, the Moon and stars. The article also points out the similarities between Chukchi notions and these of other peoples. Till now Chukchi reindeer herders seek the supposed help or influence of a constellation or planet when making important sacrifices (for example, offering sacrifices in a full moon). According to the Chukchi religion the most important celestial character is the Sun. It is spoken of as an individual being (vaúrgún). In addition to the Sun, the Creator, Dawn, Zenith, Midday and the North Star also belong to the ranks of special (superior) beings. The Moon in Chukchi mythology is a man and a being in one person. It is as the ketlja (evil spirit) of the Sun. Chukchi myths about several stars (such as the North Star and Betelgeuse) resemble to a great extent these of other peoples. Keywords: astral mythology, the Moon, sacrifices, reindeer herding, the Sun, celestial bodies, Chukchi religion, constellations. The interdependence of the Earth and celestial as well as weather phenomena has a special meaning for mankind for it is the co-exist- ence of the Sun and Moon, day and night, wind, rainfall and soil that creates life and warmth and provides the daily bread. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

Social Transition in the North, Vol. 1, No. 4, May 1993

\ / ' . I, , Social Transition.in thb North ' \ / 1 \i 1 I '\ \ I /? ,- - \ I 1 . Volume 1, Number 4 \ I 1 1 I Ethnographic l$ummary: The Chuko tka Region J I / 1 , , ~lexdderI. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. ~dgo~avlensly Ethnographic Summary: The Chukotka Region Alexander I. Pika, Lydia P. Terentyeva and Dmitry D. Bogoyavlensky May, 1993 National Economic Forecasting Institute Russian Academy of Sciences Demography & Human Ecology Center Ethnic Demography Laboratory This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DPP-9213l37. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recammendations expressed in this material are those of the author@) and do not ncccssarily reflect the vim of the National Science Foundation. THE CHUKOTKA REGION Table of Contents Page: I . Geography. History and Ethnography of Southeastern Chukotka ............... 1 I.A. Natural and Geographic Conditions ............................. 1 I.A.1.Climate ............................................ 1 I.A.2. Vegetation .........................................3 I.A.3.Fauna ............................................. 3 I1. Ethnohistorical Overview of the Region ................................ 4 IIA Chukchi-Russian Relations in the 17th Century .................... 9 1I.B. The Whaling Period and Increased American Influence in Chukotka ... 13 II.C. Soviets and Socialism in Chukotka ............................ 21 I11 . Traditional Culture and Social Organization of the Chukchis and Eskimos ..... 29 1II.A. Dwelling .............................................. -

Towards a Typological Classification of Modern Greek

TYPOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF MODERN GREEK d n singular on the head verb inflectional agreement marker for the 3r perso CHARITON CHARITONIOIS in [2] above; . b 1 by means of affixes, cf. (e) addition of adverbia~ elements mto the ver comp ex Towards a Typological Classification of Modern Greek the intensifier pard- 10 [3]; [3] para-tr6go excessively-I.eat 'overeat' Abstract . 1 1 t which can be filled with specific morpheme types, cf. the In the area of the Modern Greek verb, phenomena which consistently appear are head (f) many poten.tla s]o s d [5] hich show a strict order of their contained ele- complexes 10 [4 an ., w marking, many potential slots before and/or after the verb root, noun and adverb incor poration, addition of adverbial elements by means of affixes, a large inventory of bound ments; morphemes, verbal words as minimal sentences, etc. These features relate Modern Greek l4] dhen-tu-to-ksana-leo to polysynthesis. The main bulk of this paper is dedicated to the comparison of affixal and NEG-to. him-it -again-I .say incorporation patterns between Modern Greek and the polysynthetic languages Abkhaz, '1 don't say it to hirn again.' Cayuga, Chukchi, Mohawk, and Nahuatl. Ultimately, a typological outlook for Modern Greek is proposed. [5] sixno-afto-dhiafimizete4 often-self-advertise:IND.NONACT .1SG.PRES 'He often advertises hirnself.' 1. Clustering of polysynthetic features in Modern Greek (g) non-configurational ~yntax, cf. the possible word orders SVO, VSO, etc.; The comparison between the features which tend to cluster in polysynthetic lan (h) head-marking inflectl?n [2] ab?ve)(h) . -

Culture of Peace

CULTURE OF PEACE www.ignca.gov.in CULTURE OF PEACE Edited by BAIDYANATH SARASWATI 1999, xvii+262pp. ISBN 81-246-0124-0, Rs. 600(HB) CONTENTS Is peace a dream? A Utopian abstraction in a Foreword (Kapila Vatsyayan) dehumanized, fragmented Prologue world, stockpiling all- Introduction ( Baidyanath Saraswati) devastating war machines? And can we possibly uphold the culture of peace amidst PART-I SHARING THE EXPERIENCE OF BEAUTY AND PEACE the growing cult of violence and blind consumerism, or in 1. The Cosmos and Humanity as a Healing Family (Minoru Kasai) a climate of distrust, 2. The True Meaning of Peace from the Chinese Literary acrimony and intolerance? Perspective (Tan Chung) Embodying the presentations 3. Buddhist Art, The Mission of Harmonious Culture (Jin Weinuo) of an Asian Conference: 25- 4. Satyam, Sivam, Sundaram (Natalia Kravtchenko & Vladimir 29 November 1996 in New Zaitsev) Delhi on "The Culture of 5. Creative Hence a Peaceful Society (Devi Prasad) Peace: the Experiences and 6. Peace as Theatrical Experience (Bharat Gupt) the Experiments", this volume addresses these and PART-II EXAMINING THE EMPERICAL REALITY OF BEAUTY AND other kindred questions, with PEACE a rare insightfulness. 7. A Dehumanized Environment (Keshav Malik) Cutting across narrow compartmentalizations of 8. Modernity and Individual Responsibility (M M Agrawal) disciplines, some of the best 9. The Illusion of Seeking Peace (S C Malik) minds from Asian countries 10. Man in his becoming : A change of perspective (Mira Aster Patel) here share, with wider audiences, their concern for 1 CULTURE OF PEACE www.ignca.gov.in PART-III WORKING TOWARDS THE RESTORATION OF PEACE peace, situating their sensuous/intellectual/spiritual 11. -

2015 U.S.– China Film Gala Dinner

2015 U.S.– China Film Gala Dinner november 5, 2015 ASIA SOCIETY SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA dorothy chandler pavilion los angeles, california asiasociety.org/us-china-film-summit ASIA SOCIETY SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 2015 Summit and Gala Sponsor 2015 U.S.-China Film Gala Dinner November 5, 2015 | Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles WELCOME KARA WANG AND JEFF LOCKER Emcees THOMAS E. MCLAIN Chairman, Asia Society Southern California; Trustee, Asia Society DOMINIC NG Chairman and CEO, East West Bancorp PRESENTATION OF THE U.S.-CHINA FILM INDUSTRY LEADERSHIP AWARD ZHANG ZHAO CEO, Le Vision Pictures DINNER SUMMIT AND DINNER SPONSOR REMARKS GAO YANG President, Yucheng-Zhongluan Investment Co. PRESENTATION OF THE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD ZHANG YIMOU Director CLOSING REMARKS JONATHAN KARP Executive Director, Asia Society Southern California Welcome Lifetime Achievement Award Zhang Yimou Dear Friends, Partners and Honored Guests, ZHANG Yimou Director Zhang Yimou is widely considered one of the world’s greatest filmmakers. He began his film career at the Beijing Film Acade- On behalf of Asia Society Southern California and our Entertainment & Media in Asia (EMASIA) my in 1978, joining a prestigious group of students who would go on to become the Fifth Generation of Chinese filmmakers. program, we would like to welcome you to the Gala Dinner of our Sixth Annual U.S.-China Film Summit. We are delighted you have joined us and we’re grateful to our honorees, sponsors After starting as a cinematographer, Zhang made his directorial debut in 1987 with the now-classic Red Sorghum. The film and Summit committee members for making it such a special evening. -

Glimpses of the Glassy Sea.Pdf

IBT RussiaTanya — 25th Prokhorova Anniversary Edition Tanya Prokhorova Glimpses of theGlimpses Glassy of the Glassy Sea Sea Bible Translation into a Multitude of Tongues Biblein the Post-Soviet Translation World into a Multitude of Tongues in the Post-Soviet World InstituteInstitute for for Bible Bible TranslationTranslation MoscowMoscow 20202020 Tanya Prokhorova Glimpses of the Glassy Sea Bible Translation into a Multitude of Tongues in the Post-Soviet World ISBN 978-5-93943-285-6 © Institute for Bible Translation, 2020 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................... 5 ABKHAZ. “The Abkhaz Bible translation should not resemble lumpy dough” .............................................................................................. 7 ADYGHE + KABARDIAN. They all call themselves “Adyg” ............................... 10 ADYGHE. “These words can’t really be from the Bible, can they?” ................ 13 ALTAI. Daughter of God and of her own people ............................................ 16 ALTAI. “We’ve found the lost book!” ............................................................. 19 BALKAR. Two lives that changed radically ..................................................... 22 BASHKIR. “The Injil is the book of life” ........................................................ 26 CHECHEN + CRIMEAN TATAR. The Bible and its translators ........................... 29 CHUKCHI. “When the buds burst forth…”..................................................... -

The Emergence of Literary Ethnography in the Russian Empire: from the Far East to the Pale of Settlement, 1845-1914 by Nadezda B

THE EMERGENCE OF LITERARY ETHNOGRAPHY IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE: FROM THE FAR EAST TO THE PALE OF SETTLEMENT, 1845-1914 BY NADEZDA BERKOVICH DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Harriet Murav, Chair and Director of Research Associate Professor Richard Tempest Associate Professor Eugene Avrutin Professor Michael Finke ii Abstract This dissertation examines the intersection of ethnography and literature in the works of two Russian and two Russian Jewish writers and ethnographers. Fyodor Dostoevsky, Vladimir Korolenko, Vladimir Bogoraz, and Semyon An-sky wrote fiction in the genre of literary ethnography. This genre encompasses discursive practices and narrative strategies in the analysis of the different peoples of the Russian Empire. To some extent, and in some cases, these authors’ ethnographic works promoted the growth of Russian and Jewish national awareness between 1845 and 1914. This dissertation proposes a new interpretive model, literary ethnography, for the study of the textualization of ethnic realities and values in the Russian Empire in the late nineteenth-century. While the writers in question were aware of the ethnographic imperial discourses then in existence, I argue that their works were at times in tune with and reflected the colonial ambitions of the empire, and at other times, contested them. I demonstrate that the employment of an ethnographic discourse made possible the incorporation of different voices and diverse cultural experiences. My multicultural approach to the study of the Russian people, the indigenous peoples of the Russian Far East, and the Jews of Tsarist Russia documents and conceptualizes the diversity and multi-voicedness of the Russian Empire during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. -

Electronic Scientific Journal «Arctic and North»

ISSN 2221-2698 Electronic Scientific journal «Arctic and North» Arkhangelsk 2013. №12 Arctic and North. 2013. № 12 2 ISSN 2221-2698 Arctic and North. 2013. № 12 Electronic periodical edition © Northern (Arctic) Federal University named after M. V. Lomonosov, 2013 © Editorial Board of the Electronic Journal ‘Arctic and North’, 2013 Published at least 4 times a year The journal is registered: in Roskomnadzor as electronic periodical edition in Russian and English. Evidence of the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, information technology and mass communications El. number FS77-42 809 of 26 November 2010; in The ISSN International Centre – in the world catalogue of the serials and prolonged re- sources. ISSN 2221-2698; in the system of the Russian Science Citation Index. License agreement. № 96-04/2011R from the 12 April 2011; in the Depository in the electronic editions FSUE STC ‘Informregistr’ (registration certificate № 543 от 13 October 2011) and it was also given a number of state registrations 0421200166. in the database EBSCO Publishing (Massachysets, USA). Licence agreement from the 19th of December 2012. Founder – Northern (Arctic) Federal University named after M. V. Lomonosov. Chef Editor − Lukin Yury Fedorovich, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor. Money is not taken from the authors, graduate students, for publishing articles and other materials, fees are not paid. An editorial office considers it possible to publish the articles, the conceptual and theoretical positions of the authors, which are good for discussion. Published ma- terials may not reflect the opinions of the editorial officer. All manuscripts are reviewed. The Edi- torial Office reserves the right to choose the most interesting and relevant materials, which should be published in the first place. -

Guo Gu (Professor Jimmy Yu) Is a Worthy Heir to the Great Chan Master Sheng Yen

“A very helpful guide to the investigation of the Zen kōan from a perspective not yet widely known in the West. Guo Gu (Professor Jimmy Yu) is a worthy heir to the great Chan master Sheng Yen. He provides lucid comments on each of the cases in the classic kōan collection, the Gateless Gate, inviting us into our own intimate encounter with Zen’s ancestors and our own personal experience of the great matter of life and death. Anyone interested in understanding what a kōan really is, how it can be used, and how it uses us, will be informed and enriched by this book. I highly recommend it.” —James Ishmael Ford, author of If You’re Lucky, Your Heart Will Break and co-editor of The Book of Mu: Essential Writings on Zen’s Most Important Koan “Guo Gu’s translation of The Gateless Barrier and his commentary reveal a fresh, eminently practical approach to the famous text. Reminding again and again that it is the reader’s own spiritual affairs to which each kōan points, Guo Gu writes with both broad erudition and the profound insight of a Chan practitioner; in this way he reveals himself to be a worthy inheritor of his late Master Sheng Yen’s teachings. Zen students, called upon to give life to these kōans within their own practice, will find Passing Through the Gateless Barrier a precious resource.” —Meido Moore Roshi, abbot of Korinji Zen Monastery “A fresh, original translation and commentary by a young Chinese teacher in the tradition of Sheng Yen. -

The Phono-Typological Distances Between Ainu and the Other World Languages As a Clue for Closeness of Languages

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 77, 2008, 1, 40-62 THE PHONO-TYPOLOGICAL DISTANCES BETWEEN AINU AND THE OTHER WORLD LANGUAGES AS A CLUE FOR CLOSENESS OF LANGUAGES Yuri Tambovtsev Department of English, Linguistics and Foreign Languages of KF, Novosibirsk Pedagogical University, 28, Vilyuiskaya Str., Novosibirsk, 630126, Russia [email protected] The article deals with one of the genetically isolated languages - Ainu. It is usually a common practice in linguistics to provide a genetic identification of a language. The generic identity of a language is the language family to which it belongs.1 Therefore, is advisable to find a family for every isolated language. The new method of phonostatistics proposed here allows a linguist to find the typological distances between Ainu and the other languages of different genetic language families. The minimum distances may be a good clue for placing Ainu in this or that language family. The result of the investigation shows the minimum typological distance between Ainu and the Quechuan family (American Indian languages). Key words:consonants, phonological, distance, typology, frequency of occurrence, speech sound chain, statistics, closeness Ainu is a genetically isolated language.2 There are many different theories as to the origin and ethnic development of Ainu. Some scholars think they belong to the Manchu-Tungus tribes while others link them to the Palaeo- Asiatic peoples. A. P. Kondratenko and M. M. Prokofjev point out that some 1 WHALEY, L.J. Introduction to Typology: The Unity and Diversity of Language, pp. 18-23. 2 CRYSTAL, D. An Ecyclopedic Dictionary of Language and Languages, p. 11 and also Jazyki i dialekty mira.