17 Learning Disabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autism Europe

N o 5265 June 2016 English Edition Autism - Europe Our campaign: Respect, Acceptance, Inclusion “On the High Seas”: A film to promote the inclusion of children with autism Jon Spiers, Chief Executive of Autistica, on the report denouncing early death among autistic people Adam Bradford, self-advocate and Queen’s Young Leader 2016: “I hope this recognition inspires other young autistic people to reach their goals” Autism-Europe’s 11th International Congress: Keynote speakers announced Published by Autism-Europe Afgiftekantoor - Bureau de dépôt : Brussels - Ed. responsable : Z. Szilvasy For Diversity Autism-Europe aisbl Rue Montoyer, 39 • B - 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel.:+32-2-675 75 05 - Fax:+32-2-675 72 70 Against Discrimination E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.autismeurope.org SUMMARY Activities - World Autism Awareness Day campaign 2016 ................... 3 - Autism-Europe’s Annual General Assembly 2016 in Cagliari, Italy .............................................................. 7 News & FeAtures - The “On the High Seas” project ....................................... 8 - Premature mortality among persons with autism. Interview with Jon Spiers, Chief Executive of Autistica .................. 10 - App “Oral Health – SOHDEV” improving oral health Dear friends, for people with autism ................................................... 12 It is with great pleasure that we present this latest edition - Interview with Adam Bradford, self-advocate of our LINK magazine, which offers an overview of Autism- and Queen’s Young Leader 2016 ................................... 13 Europe’s recent activities as well as news from a range - Keynotes speakers announced for Autism-Europe’s th of different stakeholders in the world of autism. In this 11 International Congress ........................................... 14 issue, you will be able to get to know our new member - The “Eight Points” project ............................................ -

Summary of Responses by Question

dialoguebydesign making consultation work Adult Autism Strategy consultation A summary of the submissions received in response to the online consultation Prepared for the Department of Health By Dialogue by Design Ltd January 2010 Adult autism consultation summary report – January 2010 Page 1 dialoguebydesign making consultation work Table of contents 1. Executive Summary ...............................................................................................3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................5 2.1. Background..................................................................................................5 2.2. How the consultation process was managed...............................................5 2.3. Responses...................................................................................................5 2.4. Participation statistics ..................................................................................5 2.5 Reading this summary and interpreting the results......................................9 3. Consultation overview ..........................................................................................10 3.1. Summary of responses to this chapter.......................................................10 3.2. Standard consultation questions ................................................................11 3.7. Easy-read consultation questions ..............................................................26 4. Social -

Multisensory Work Multisensory

Multisensory Work Interdisciplinary approach to multisenory methods Multisensory Work - Interdisciplinary apporach to MSW Multisensory Work & ALa-Opas (eds.): Sirkkola, Veikkola Multisensory Work .... Marja Sirkkola, Päivi Veikkola & Tuomas Ala-Opas (eds.) HAMK ISBN 978-951-784-464-2 ISSN 1795-4231 HAMKin julkaisuja 5/2008 Interdisciplinary approach to multisensory work Local definitions and developmental projects Marja Sirkkola, Päivi Veikkola & Tuomas Ala-Opas (eds.) HAMK University of Applied Sciences Marja Sirkkola, Päivi Veikkola & Tuomas Ala-Opas (eds.) Interdisciplinary approaches to multisensory work Local definitions and developmental projects ISSN 978-951-784-476-5 ISSN 1795-424X HAMKin e-julkaisuja 7/2008 © Hamk University of Applied Sciences, editors PUBLISHER Hamk University of Applied Sciences PL 230 13101 HÄMEENLINNA puh. (03) 6461 faksi (03) 646 4259 [email protected] www.hamk.fi/julkaisut Hämeenlinna, December 2008 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 5 Marja Sirkkola, Tuomas Ala-Opas Introduction to Multisensory Work ....................................................................................... 7 Marja Sirkkola, Päivi Veikkola & Tuomas Ala-Opas Professional specialization studies in Multisensory Work ................................................... 12 Jaakko Salonen Interactive multisensory sound room - How is the room being used by clients and staff? .. 16 Satu Selvinen The use of multisensory games as support -

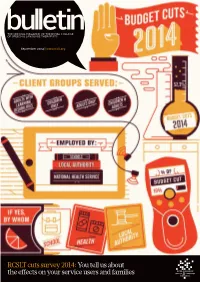

RCSLT Cuts Survey 2014:You Tell Us About the Effects on Your Service Users and Families

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPISTS September 2014 | www.rcslt.org RCSLT cuts survey 2014: You tell us about the eff ects on your service users and families 001_cover.indd 1 18/08/2014 14:33 The perfect choice for instant food thickening [email protected] www.thickenaid.co.uk 01942 816 184 Supporting you through Dysphagia The instant food thickener specially designed for the dietary management of people with Dysphagia Blends quickly & efficiently : Whether dinner or a snack, Thicken Aid acts with speed Consistency : Thicken Aid thickens liquids hot or cold and pureed foods to any required consistency 25% cost saving : Compared to the leading prescribed brand, Thicken Aid saves the NHS money! Call 01942942 816 184 todaytoday forfoor a freefree samplesamp for testinging at yyourour nexnextt tteameam mmeeting,eeting, or for furtherurther infinformation.ormation. Available on Drug Tariff. Thicken Aid is available in 225g re-sealable tubs & 100 x 9g 28 Bulletin MayMMaay sachets20142014 | www.rcslt.orgww.rcslt.org BBUL.09.14.002.inddUL.09.14.002.indd SSec1:28ec1:28 18/08/2014 10:07 Contents ISSUE 749 4 Letters 5 News →It’s RCSLT conference time in Leeds →Queen’s award for Therapy Box →Get involved in 8 dementia research 11 Opinion: Lipreading: an evolving role opportunity for SLTs? 12 Steven Harulow: Cuts 2014: 5 10 the eff ects on your services 16 Antonia Kilcommons: A pioneering rehabilitation service for children with 22 brain tumours 20 The Research and Development Forum 22 Gaye Powell, Dominique Lowenthal: -

Access to Health and Social Care Services for Norfolk Families with Autism

Image by Catherine Scott, (2012). Access to health and social care services for Norfolk families with Autism Steph Tuvey, Project Manager Please contact Healthwatch Norfolk if you require an easy read; large print or a translated copy of this report. Postal address: Healthwatch Norfolk, Suite 6 – Elm Farm, Norwich Common, Norfolk, NR18 0SW Email address: [email protected] Telephone: 0808 168 9669 October, 2018 Contents Who we are and what we do 1 Acknowledgements 1 Glossary 2-4 Summary 5-6 1. Recommendations 7 2. Why we looked at this 8-12 2.1 Autistic Spectrum Disorder in the UK today 8-10 2.2 ASD in Norfolk Today 10-11 2.3 ASD diagnostic services for children in Norfolk 11-12 3. How we did this 13-16 3.1 Aims 13 3.2 Project approach 13-14 3.3 Parent questionnaire 14-15 3.4 Parent support groups 15 3.5 ASD public events 15 3.6 Data processing and analysis 16 3.7 Strengths and Limitations 16 4. What we found out 17-53 4.1 About the families 17-18 4.2 Using health and social care services 18 4.2.1 What has worked well? 19-22 4.2.2 Barriers and improvements needed 22-31 4.3 ASD diagnosis 31-36 4.4 Family support 37-44 4.4.1 What support parents tried to access 37-41 4.4.2 Support families valued the most 41-44 4.4.3 Further support felt they needed 44-49 4.5 Good Practice in Health and social care services 49-53 4.5.1 Other good practice within the community 53 5. -

Participation and Empowerment in Sociocultural Multisensory Work

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Sirkkola, Eila Marja Aulikki (2009) Multisensory environments in social care: participation and empowerment in sociocultural multisensory work. Professional Doctorate (Research) thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/32587/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/32587/ Multisensory Environments in social care: Participation and empowerment in sociocultural multisensory work Thesis submitted by Eila Marja Aulikki Sirkkola In August, 2009 for the degree of Doctor of Education in the School of Education James Cook University Statement of access I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. ii Statement of sources I declare that this portfolio thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. -

Download the Book of Abstracts

12th Autism-Europe International Congress September 13-15th 2019 ABSTRACT BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by Zsuzsanna Szilvásy - President of Autism-Europe p. 1 Foreword by Danièle Langloys - President of Autisme France p. 1 Scientific Committee p. 2 Honorary Scientific Committee p. 3 Index by session p. 4 First author index p.17 Index by Keywords p.26 Abstracts p.28 We are glad to invite you to the 12th In- how to shape better lives for autistic people. have happy and fulfilling lives. ternational Congress of Autism-Europe , which is organized in cooperation with Au- On the occasion of this three-day event With kindest regards, tisme France, in the beautiful city of Nice. people from all over the world will come Our congresses are held every three years, together to share the most recent deve- and we are delighted to be back in France, lopments across the field of autism. The 36 years after the congress of Paris. It will congress will address a wide range of is- be a great opportunity to take stock of the sues, including: diagnostic and assess- progress achieved and look at the opportu- ment, language and communication, ac- nities ahead. cess to education, employment, research and ethics, gender and sexuality, inclusion The 2019 congress’ motto is “A new Dyna- and community living, mental and physical mic for Change and Inclusion”, in keeping health, interventions, strategic planning with our aspiration that international scienti- and coordination of services as well as fic research on autism should be translated rights and participation. into concrete changes and foster social in- clusion for autistic people of all ages and We hope you will enjoy this Congress, needs. -

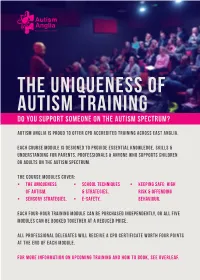

THE UNIQUENESS of AUTISM TRAINING Do You Support Someone on the Autism Spectrum?

THE UNIQUENESS OF AUTISM TRAINING Do you support someone on the autism spectrum? Autism Anglia is proud to offer CPD accredited training across east anglia. Each course module is designed to provide essential knowledge, skills & understanding for parents, professionals & anyone who supports children or adults on the autism spectrum. The course modules cover: • The Uniqueness • School Techniques • Keeping Safe: High of Autism. & Strategies. Risk & Offending • Sensory Strategies. • E-Safety. Behaviour. Each four-hour training module can be purchased independently, or all five modules can be booked together at a reduced price. All professional delegates will receive a CPD certificate worth four points at the end of each module. For more information on upcoming training and how to book, see overleaf. The Uniqueness of Autism Training 2018 4 CPD points per module unless otherwise stated Norfolk - The Willow Centre Thursday 21 June 12.30pm - 4.30pm The Uniqueness of Autism Thursday 28 June 12.30pm - 4.30pm Sensory Strategies Thursday 5 July 12.30pm - 4.30pm School Techniques & Strategies Thursday 12 July 12.30pm - 4.30pm Keeping Safe: High Risk and Offending Behaviour Thursday 19 July 12.30pm - 4.30pm E-Safety Suffolk - Kesgrave Conference Centre Thursday 1 November 1.30pm - 5.30pm The Uniqueness of Autism Thursday 8 November 1.30pm - 5.30pm Sensory Strategies Thursday 15 November 1.30pm - 5.30pm School Techniques & Strategies Thursday 22 November 1.30pm - 5.30pm Keeping Safe: High Risk and Offending Behaviour Thursday 29 November 1.30pm - 5.30pm E-Safety Autism Anglia Members: £35 per module Individuals/non-profit: £45 per module Professionals: £60 per module (CPD Points awarded) For more information and to book, visit autism-anglia.org.uk call 01206 577678 or email [email protected]. -

Daily Report Tuesday, 23 July 2019 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 23 July 2019 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 23 July 2019 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:35 P.M., 23 July 2019). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Heating: Rural Areas 14 ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 Housing: Electricity 15 Attorney General: Ethnic Housing: Insulation 16 Groups 7 Insolvency 17 Attorney General: Working Manufacturing Industries 17 Hours 7 New Businesses 20 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Research: Expenditure 20 Avara Avlon Pharma Services: Research: Finance 20 Insolvency 8 Research: Investment 21 Boilers: Standards 8 Seabed: Mining 21 Carbon Emissions: EU UK Seabed Resources: Pacific Countries 9 Ocean 21 Clean Growth Ministerial Waste Heat Recovery 22 Group 10 Wind Power 22 Companies House: Fraud 10 CABINET OFFICE 23 Design of UK Funding Cabinet Office: Credit Unions 23 Schemes for European and International Collaboration Constituencies 23 Review 11 Emergencies: Planning 23 Directors: Personation 11 Huawei: 5G 24 District Heating 12 Members: Correspondence 24 Electricity 12 DEFENCE 24 Energy: EU Grants and Loans 13 Armed Forces Covenant: Environment Protection: Veterans 24 Employment 13 Armed Forces: Pay 25 Heat Trust 13 Defence Fire and Rescue Service 25 Defence Fire and Rescue Personal, Social, Health and Service: Serco 25 Economic Education 40 Defence Medical Services: Post-18 Education -

Useful Contacts

Useful Contacts Please find below some links to local and national organisations and charities you may find interesting and useful. (Please note: the NAS does not endorse any of the non-NAS services or individuals we provide a platform for in emails or on any of our social media platforms. Some services may require payment.) National Autistic Society help: https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/help-and- support •The Transition Support Helpline provides advice and support to young autistic people and their families on making the transition from school, further or higher education to adult life. https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/help-and- support/transition-support-service •Parent to Parent is a confidential telephone service providing emotional support to parents and carers of autistic adults or children. The service is provided by trained parent volunteers who are all parents of an autistic adult or child. https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/help-and-support/parent-to-parent •If you cannot find the support you are looking for on the website please contact The Autism Helpline enquiry service which provides impartial, confidential information and advice for autistic people, their families, friends, and carers. ➢Telephone: 0808 800 4104 – 10am-3pm https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we- do/contact-us/online-enquiry-form •My Health Passport – a helpful booklet to complete to take to all hospital visits for staff to be aware of autism or other related issues: https://www.autism.org.uk/advice- and-guidance/topics/physical-health/my-health-passport -

CEO Report 7

Contents Page Vision and Mission 3 Chairman’s Report 4 Acknowledgements 6 CEO Report 7 Community Development 10 Business Bank 13 Community Accounts 14 Volunteer Centre and Timebank 16 Transport and Shopmobility 21 Highlights of the Year 24 Treasurer Report 26 Presidents and Trustees 30 Staff 31 Volunteers 32 Membership 33 Future 35 Contents Page Contents Vision and Mission “Thriving local communities” CCVS will enable affective communities and voluntary action by empowering and inspiring our local society through our five core values – Support, Development, Liaison, Representation and Strategic Partnership Working. 3 Chairman Report Dear Colleague before, the need just keeps growing as compliance becomes ever complicated. It is with great pride that I offer you the The rise of the need for an audit has end of year Annual Report for 2015. risen to £1M, which means we have more scope to support medium to larger This is my seventh and final Report as size groups further. Chairman of CCVS, as I intend to hand this role over to a very capable With the increase in the volume of work successor at this year’s Annual General and staff, Trustees embarked on a Meeting – Cate Hammett. building renewal and refurbishment programme at Winsley’s House, which is As in previous years, I would like to thank now complete, and celebrated its official our growing number of volunteers and opening on September 10th 2015. supporters. We are moving Shopmobility back within Some very special thanks need to be Winsley's House and Community given to Tracy Rudling, our very hard- Transport has re-located out of the town working CEO, and her team, who have centre due to the planned move. -

FOH Directory of Services – Mid Essex

FOH Directory of Services – Mid Essex Child Behavioural Asylum Seeker/Refugee Bereavement/Loss Children’s Centres Difficulties Crime/Anti-Social Disability/Additional Domestic Abuse Education Behaviour Needs Health Visiting & School Employment Family Conflict Financial Concerns Nursing Services Lonely/Isolated, Housing Concerns Legal Mental Health Socially Alienated Parental Safeguarding Sexual Abuse/CSE Substance Misuse Routine/Boundaries Victim of Bullying Young Carer Asylum Seeker/Refugee A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Back to Mid Home Page Asylum Aid Asylum Aid is an independent, national charity working to secure protection for people seeking refuge in the UK from persecution and human rights abuses abroad. We provide Tel: 0207 3549264 free legal advice and representation to the most vulnerable and excluded asylum seekers, Email: [email protected] and lobby and campaign for an asylum system based on inviolable human rights principles. Website: www.asylumaid.org.uk Read More Citizens Advice Bureau - Braintree The Citizens Advice service offers practical, up-to-date information and advice on a wide range of topics, including; debt, benefits, housing, legal, discrimination, employment, Tel: 03444 994719 (General Advice line) immigration, consumer and other problems. Tel: 01787 479397 (Disability Outreach) Email: [email protected] Website: www.bhwcab.org.uk Address: 17 Coggeshall Road, Braintree, Essex. CM7 9DB Citizens Advice Bureau - Chelmsford The Citizens Advice service offers practical, up-to-date information and advice on a wide range of topics, including; debt, benefits, housing, legal, discrimination, employment, Tel: 01245 205656 (Advice Line) immigration, consumer and other problems.