Causality and Objectivity: the Arguments in Kant's Second Analogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Using Analogy to Learn About Phenomena at Scales Outside Human Perception Ilyse Resnick1*, Alexandra Davatzes2, Nora S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Resnick et al. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications (2017) 2:21 Cognitive Research: Principles DOI 10.1186/s41235-017-0054-7 and Implications ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Using analogy to learn about phenomena at scales outside human perception Ilyse Resnick1*, Alexandra Davatzes2, Nora S. Newcombe3 and Thomas F. Shipley3 Abstract Understanding and reasoning about phenomena at scales outside human perception (for example, geologic time) is critical across science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Thus, devising strong methods to support acquisition of reasoning at such scales is an important goal in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. In two experiments, we examine the use of analogical principles in learning about geologic time. Across both experiments we find that using a spatial analogy (for example, a time line) to make multiple alignments, and keeping all unrelated components of the analogy held constant (for example, keep the time line the same length), leads to better understanding of the magnitude of geologic time. Effective approaches also include hierarchically and progressively aligning scale information (Experiment 1) and active prediction in making alignments paired with immediate feedback (Experiments 1 and 2). Keywords: Analogy, Magnitude, Progressive alignment, Corrective feedback, STEM education Significance statement alignment and having multiple opportunities to make Many fundamental science, technology, engineering, and alignments are critical in supporting reasoning about mathematic (STEM) phenomena occur at extreme scales scale, and that the progressive and hierarchical that cannot be directly perceived. For example, the Geo- organization of scale information may provide salient logic Time Scale, discovery of the atom, size of the landmarks for estimation. -

Analogical Processes and College Developmental Reading

Analogical Processes and College Developmental Reading By Eric J. Paulson Abstract: Although a solid body of research is analogical. An analogical process involves concerning the role of analogies in reading processes the identification of partial similarities between has emerged at a variety of age groups and reading different objects or situations to support further proficiencies, few of those studies have focused on inferences and is used to explain new concepts, analogy use by readers enrolled in college develop- solve problems, and understand new areas and mental reading courses. The current study explores ideas (Gentner, & Colhoun, 2010; Gentner & Smith, whether 232 students enrolled in mandatory (by 2012). For example, when a biology teacher relates placement test) developmental reading courses the functions of a cell to the activities in a factory in in a postsecondary educational context utilize order to introduce and explain the cell to students, analogical processes while engaged in specific this is an analogical process designed to use what reading activities. This is explored through two is already familiar to illuminate and explain a separate investigations that focus on two different new concept. A process of mapping similarities ends of the reading spectrum: the word-decoding between a source (what is known) and a target Analogy appears to be a key level and the overall text-comprehension level. (what is needed to be known) in order to better element of human thinking. The two investigations reported here build on understand the target (Holyoak & Thagard, 1997), comparable studies of analogy use with proficient analogies are commonly used to make sense of readers. -

Causality and Determinism: Tension, Or Outright Conflict?

1 Causality and Determinism: Tension, or Outright Conflict? Carl Hoefer ICREA and Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona Draft October 2004 Abstract: In the philosophical tradition, the notions of determinism and causality are strongly linked: it is assumed that in a world of deterministic laws, causality may be said to reign supreme; and in any world where the causality is strong enough, determinism must hold. I will show that these alleged linkages are based on mistakes, and in fact get things almost completely wrong. In a deterministic world that is anything like ours, there is no room for genuine causation. Though there may be stable enough macro-level regularities to serve the purposes of human agents, the sense of “causality” that can be maintained is one that will at best satisfy Humeans and pragmatists, not causal fundamentalists. Introduction. There has been a strong tendency in the philosophical literature to conflate determinism and causality, or at the very least, to see the former as a particularly strong form of the latter. The tendency persists even today. When the editors of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy asked me to write the entry on determinism, I found that the title was to be “Causal determinism”.1 I therefore felt obliged to point out in the opening paragraph that determinism actually has little or nothing to do with causation; for the philosophical tradition has it all wrong. What I hope to show in this paper is that, in fact, in a complex world such as the one we inhabit, determinism and genuine causality are probably incompatible with each other. -

Studies on Causal Explanation in Naturalistic Philosophy of Mind

tn tn+1 s s* r1 r2 r1* r2* Interactions and Exclusions: Studies on Causal Explanation in Naturalistic Philosophy of Mind Tuomas K. Pernu Department of Biosciences Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences & Department of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies Faculty of Arts ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki, in lecture room 5 of the University of Helsinki Main Building, on the 30th of November, 2013, at 12 o’clock noon. © 2013 Tuomas Pernu (cover figure and introductory essay) © 2008 Springer Science+Business Media (article I) © 2011 Walter de Gruyter (article II) © 2013 Springer Science+Business Media (article III) © 2013 Taylor & Francis (article IV) © 2013 Open Society Foundation (article V) Layout and technical assistance by Aleksi Salokannel | SI SIN Cover layout by Anita Tienhaara Author’s address: Department of Biosciences Division of Physiology and Neuroscience P.O. Box 65 FI-00014 UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI e-mail [email protected] ISBN 978-952-10-9439-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-9440-8 (PDF) ISSN 1799-7372 Nord Print Helsinki 2013 If it isn’t literally true that my wanting is causally responsible for my reaching, and my itching is causally responsible for my scratching, and my believing is causally responsible for my saying … , if none of that is literally true, then practically everything I believe about anything is false and it’s the end of the world. Jerry Fodor “Making mind matter more” (1989) Supervised by Docent Markus -

Causation As Folk Science

1. Introduction Each of the individual sciences seeks to comprehend the processes of the natural world in some narrow do- main—chemistry, the chemical processes; biology, living processes; and so on. It is widely held, however, that all the sciences are unified at a deeper level in that natural processes are governed, at least in significant measure, by cause and effect. Their presence is routinely asserted in a law of causa- tion or principle of causality—roughly, that every effect is produced through lawful necessity by a cause—and our ac- counts of the natural world are expected to conform to it.1 My purpose in this paper is to take issue with this view of causation as the underlying principle of all natural processes. Causation I have a negative and a positive thesis. In the negative thesis I urge that the concepts of cause as Folk Science and effect are not the fundamental concepts of our science and that science is not governed by a law or principle of cau- sality. This is not to say that causal talk is meaningless or useless—far from it. Such talk remains a most helpful way of conceiving the world, and I will shortly try to explain how John D. Norton that is possible. What I do deny is that the task of science is to find the particular expressions of some fundamental causal principle in the domain of each of the sciences. My argument will be that centuries of failed attempts to formu- late a principle of causality, robustly true under the introduc- 1Some versions are: Kant (1933, p.218) "All alterations take place in con- formity with the law of the connection of cause and effect"; "Everything that happens, that is, begins to be, presupposes something upon which it follows ac- cording to a rule." Mill (1872, Bk. -

Demonstrative and Non-Demonstrative Reasoning by Analogy

Demonstrative and non-demonstrative reasoning by analogy Emiliano Ippoliti Analogy and analogical reasoning have more and more become an important subject of inquiry in logic and philosophy of science, especially in virtue of its fruitfulness and variety: in fact analogy «may occur in many contexts, serve many purposes, and take on many forms»1. Moreover, analogy compels us to consider material aspects and dependent-on-domain kinds of reasoning that are at the basis of the lack of well- established and accepted theory of analogy: a standard theory of analogy, in the sense of a theory as classical logic, is therefore an impossible target. However, a detailed discussion of these aspects is not the aim of this paper and I will focus only on a small set of questions related to analogy and analogical reasoning, namely: 1) The problem of analogy and its duplicity; 2) The role of analogy in demonstrative reasoning; 3) The role of analogy in non-demonstrative reasoning; 4) The limits of analogy; 5) The convergence, particularly in multiple analogical reasoning, of these two apparently distinct aspects and its philosophical and methodological consequences; § 1 The problem of analogy and its duplicity: the controversial nature of analogical reasoning One of the most interesting aspects of analogical reasoning is its intrinsic duplicity: in fact analogy belongs to, and takes part in, both demonstrative and non-demonstrative processes. That is, it can be used respectively as a means to prove and justify knowledge (e.g. in automated theorem proving or in confirmation patterns of plausible inference), and as a means to obtain new knowledge, (i.e. -

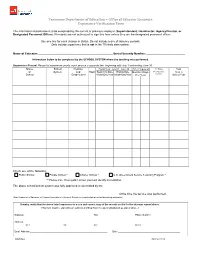

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2019 A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry Karina Bucciarelli Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Epistemology Commons, Feminist Philosophy Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons Recommended Citation Bucciarelli, Karina, "A Feminist Epistemological Framework: Preventing Knowledge Distortions in Scientific Inquiry" (2019). Scripps Senior Theses. 1365. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1365 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK: PREVENTING KNOWLEDGE DISTORTIONS IN SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY by KARINA MARTINS BUCCIARELLI SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR SUSAN CASTAGNETTO PROFESSOR RIMA BASU APRIL 26, 2019 Bucciarelli 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank my wonderful family for supporting me every step of the way. Mamãe e Papai, obrigada pelo amor e carinho, mil telefonemas, conversas e risadas. Obrigada por não só proporcionar essa educação incrível, mas também me dar um exemplo de como viver. Rafa, thanks for the jokes, the editing help and the spontaneous phone calls. Bela, thank you for the endless time you give to me, for your patience and for your support (even through WhatsApp audios). To my dear friends, thank you for the late study nights, the wild dance parties, the laughs and the endless support. -

Objectivity in the Feminist Philosophy of Science

OBJECTIVITY IN THE FEMINIST PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requisites for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Karen Cordrick Haely, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Louise M. Antony, Adviser Professor Donald C. Hubin _______________________ Professor George Pappas Adviser Philosophy Graduate Program ABSTRACT According to a familiar though naïve conception, science is a rigorously neutral enterprise, free from social and cultural influence, but more sophisticated philosophical views about science have revealed that cultural and personal interests and values are ubiquitous in scientific practice, and thus ought not be ignored when attempting to understand, describe and prescribe proper behavior for the practice of science. Indeed, many theorists have argued that cultural and personal interests and values must be present in science (and knowledge gathering in general) in order to make sense of the world. The concept of objectivity has been utilized in the philosophy of science (as well as in epistemology) as a way to discuss and explore the various types of social and cultural influence that operate in science. The concept has also served as the focus of debates about just how much neutrality we can or should expect in science. This thesis examines feminist ideas regarding how to revise and enrich the concept of objectivity, and how these suggestions help achieve both feminist and scientific goals. Feminists offer us warnings about “idealized” concepts of objectivity, and suggest that power can play a crucial role in determining which research programs get labeled “objective”. -

Easychair Preprint the Indeterminist Objectivity of Quantum Mechanics

EasyChair Preprint № 3891 The Indeterminist Objectivity of Quantum Mechanics Versus the Determinist Subjectivity of Classical Physics Vasil Penchev EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. July 16, 2020 The indeterminist objectivity of quantum mechanics versus the determinist subjectivity of classical physics Vasil Penchev, [email protected] Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Institute of Philosophy and Sociology: Dept. of Logic and Philosophy of Science Abstract. Indeterminism of quantum mechanics is considered as an immediate corollary from the theorems about absence of hidden variables in it, and first of all, the Kochen – Specker theorem. The base postulate of quantum mechanics formulated by Niels Bohr that it studies the system of an investigated microscopic quantum entity and the macroscopic apparatus described by the smooth equations of classical mechanics by the readings of the latter implies as a necessary condition of quantum mechanics the absence of hidden variables, and thus, quantum indeterminism. Consequently, the objectivity of quantum mechanics and even its possibility and ability to study its objects as they are by themselves imply quantum indeterminism. The so-called free-will theorems in quantum mechanics elucidate that the “valuable commodity” of free will is not a privilege of the experimenters and human beings, but it is shared by anything in the physical universe once the experimenter is granted to possess free will. The analogical idea, that e.g. an electron might possess free will to “decide” what to do, scandalized Einstein forced him to exclaim (in a letter to Max Born in 2016) that he would be а shoemaker or croupier rather than a physicist if this was true.