Conversion of Upper Castes Into Lower Castes: a Process of Asprashyeekaran (Encompassing Untouchability)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secretariat Phones

H.P.SECRETARIAT TELEPHONE NUMBERS th AS ON 09 August, 2021 DESIGNATION NAME ROOM PHONE PBX PHONE NO OFFICE RESIDENCE HP Sectt Control Room No. E304-A 2622204 459,502 HP Sectt Fax No. 2621154 HP Sectt EPABX No. 2621804 HP Sectt DID Code 2880 COUNCIL OF MINISTERS CHIEF MINISTER Jai Ram Thakur 1st Floor 2625400 600 Ellerslie 2625819 Building 2620979 2627803 2627808 2628381 2627809 FAX 2625011 Oak-Over 858 2621384 2627529 FAX 2625255 While in Delhi Residence Office New Delhi Tel fax 23329678 Himachal Sadan 24105073 24101994 Himachal Bhawan 23321375 Advisor to CM + Dr.R.N.Batta 1 st Floor 2625400 646 2627219 Pr.PS.to CM Ellersile 2625819 94180-83222 PS to Pr.PS to CM Raman Kumar Sharma 2625400 646 2835180 94180-23124 OSD to Chief Minister Mahender Kumar Dharmani E121 2621007 610,643 2628319 94180-28319 PS to OSD Rajinder Verma E120 2621007 710 94593-93774 OSD to Chief Minister Shishu Dharma E16G 2621907 657 2628100 94184-01500 PS to OSD Balak Ram E15G 2621907 757 2830786 78319-80020 Pr. PS to Diwan Negi E102 2627803 799 2812250 Chief Minister 94180-20964 Sr.PS to Chief Minister Subhash Chauhan E101 2625819 785 2835863 98160-35863 Sr.PS to Chief Minister Satinder Kumar E101 2625819 743 2670136 94180-80136 PS to Chief Minister Kaur Singh Thakur E102 2627803 700 2628562 94182-32562 PS to Chief Minister Tulsi Ram Sharma E101 2625400 746,869 2624050 94184-60050 Press Secretary Dr.Rajesh Sharma E104 2620018 699 94180-09893 to C M Addl.SP. Brijesh Sood E105 2627811 859 94180-39449 (CM Security) CEO Rajeev Sharma 23 G & 24 G 538,597 94184-50005 MyGov. -

Origin of the Rajputs : ______

ORIGIN OF THE RAJPUTS : __________________________ There is no agreement among the scholars regarding the origin of the Rajputs. It has been opined by many scholars that the Rajputs are the descendants of foreign invaders like Sakas, Kushana, white- Hunas etc. All these foreigners, who permanently settled in India, were absorbed within the Hindu society and were accorded the status of the Kshatriyas. It was only afterwards that they claimed their lineage from the ancient Kshatriya families. The other view is that the Rajputs are the descendants of the ancient Brahamana or Kshatriya families and it is only because of certain circumstances that they have been called the Rajputs. Earliest and much debated opinion concerning the origin of the Rajputs is that all Rajput families were the descendants of the Gurjaras and the Gurjaras were of foreign origin. Therefore, all Rajput families were of foreign origin and only, later on, were placed among Indian Kshatriyas and were called the Rajputs. The adherents of this view argue that we find references to the Guijaras only after the 6th century when foreigners had penetrated in India. So, they were not of Indian origin but foreigners. Cunningham described them as the descendants of the Kushanas. A.M.T. Jackson described that one race called Khajara lived in Arminia in the 4th century. When the Hunas attacked India, Khajaras also entered India and both of them settled themselves here by the beginning of the 6th century. These Khajaras were called Gurjaras by the Indians. Kalhana has narrated the events of the reign of Gurjara king, Alkhana who ruled in Punjab in the 9th century. -

Religious Dichotomy Among the Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh

IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences ISSN 2455-2267; Vol.04, Issue 02 (2016) Pg. no. 387-393 Institute of Research Advances http://research-advances.org/index.php/RAJMSS Socio- Religious Dichotomy among the Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh Dr. Bindu Sahni VPO Ambota, Tehsil Amb, District Una (Himachal Pradesh), India. Type of Review: Peer Reviewed. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v4.n2.p8 How to cite this paper: Sahni, B. (2016). Socio- Religious Dichotomy among the Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh. IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences (ISSN 2455-2267), 4(2), 387-393. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jmss.v4.n2.p8 © Institute of Research Advances This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License subject to proper citation to the publication source of the work. Disclaimer: The scholarly papers as reviewed and published by the Institute of Research Advances (IRA) are the views and opinions of their respective authors and are not the views or opinions of the IRA. The IRA disclaims of any harm or loss caused due to the published content to any party. 387 IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences The Gujjars are primarily a pastoral tribe. They possess huge herds of buffaloes and in search of better grazing grounds they are constantly on the move. In Himachal Pradesh Gujjars are bracketed as a Scheduled Tribe. As per the Census of 2011, 5.7% population of Himachal Pradesh falls in the category of Scheduled Tribe. Though Gujjars are scattered all over Himachal Pradesh, their major concentrations are in Bilaspur, Chamba, Kangra and Una districts. -

Rajputs - Sailent Features

Rajputs - Sailent Features Study Materials THE RAJPUTS (AD 650-1200) Chandeta kingdom was founded by Yashovarma of Chandel in the region of Bhajeka Bhutika (later came After Harshavardhana. the Rajputs emerged as a to beknown as Bundelkhan). Their capital was powerful force in western and central India and Mahoba. Their Prominent kings were Dhanga and dominated the Indian political scene fo nearly 500 Kirthiverma. The last ruler from the dynasty merged years from the seventh century. They emerged from with Prithviraj Chauhan in AD 1182. the political chaos that surfaced after the death of Kirthiverma the Chandela ruler defeated the Harshavardhana. Out of the political disarray prevalent Chedi ruler in the eleventh century. Later, in North India, the Rajputs chalked out the small Lakshamanaraja emerged as a powerful Chedi Rajput kingdoms of Gujarat and Malwa. From the eighth to ruler. His kingdom was located between the Godavari twelfth century they struggled to keep themselves and the Narmada and his capital was Tripura (near independent. But as they grew bigger the infighting Jabalpur). made them brittle, theyfell prey to the rising Like Kanauj, Malwa was the symbol of the domination of the Muslim invaders. Among them the Rajputana power. Krishnaraja (also called King Gujara of Pratihara, the Gahadwals of Kanauj, the Upendra) founded this kingdom. Their capital was Kalachuris of Chedi, the Chauhans of Ajmer, the Dhar (Madhya Pradesh). The prominent kings from Solankis of Gujarat and the Guhtlotas of Mewar are this dynasty were Vakpatiraju- Munjana II. Bhoja I, important. Bhoja II. In Malwa, the Parmars ruled and the most The first Gujara-Pratihara ruler was famous of them was King Bhoja. -

July -2016.Xlsx

GCS Medical College, Ahmedabad 1st Year Result (July-2016) Sr. No Roll no Seat No. Name Result 1 601 246 AAROHI ATULBHAI GANDHI Pass 2 602 594 AASHVI MEHUL PATEL Pass 3 603 263 ADITYA BHAGIRATH GAUDANI Pass 4 604 598 AKASH SUNILKUMAR PATEL Pass 5 605 8 AKSHADHA EASWAR Pass 6 606 599 AKSHAY NAGINBHAI PATEL Pass 7 607 50 ANAND NILESH BHATT Pass 8 608 925 ANAND SURESHKUMAR SOLANKI Pass 9 609 948 ANIKET DALSUKHBHAI TAVIYAD Pass 10 610 862 ANISHA DHIRENKUMAR SHAH Pass 11 611 1035 ANKIT DINESHBHAI ZALA Pass 12 612 109 ANKUR GANESHBHAI CHAUDHARY Pass 13 613 765 ASHNA TUSHAR PATWA Pass 14 614 1028 AYUSHI HIMANSHUBHAI VYAS Pass 15 615 606 AYUSHIBEN BHARATBHAI PATEL Pass 16 616 18 BANSARI ASHOKBHAI BALDANIYA Pass 17 617 343 BHAVIK SURESHBHAI JINJA Pass 18 618 424 CHINTAN MEHULKUMAR LAKHANI Pass 19 619 205 DARSHANKUMAR BABUBHAI DODIA Pass 20 620 51 DEEP ASHUTOSH BHATT Pass 21 621 619 DEEP KAMLESHKUMAR PATEL Pass 22 622 392 DEVANSH JITENDRA KHANDOL Pass 23 623 178 DEVDARSHAN MAHADEVBHAI DESAI Fail 24 624 304 DHRUV ANILKUMAR GUPTA Pass 25 625 30 DHRUV HARIBHAI BARAD Fail 26 626 129 DHRUVA SUNIL CHAUHAN Pass 27 627 1041 DHRUVIN MANISHKUMAR ZAVERI Pass 28 628 631 DISHA JITENDRAKUMAR PATEL Pass 29 629 547 DIVYABEN RAJUBHAI PANCHAL Pass 30 630 868 DRASHTI BABUBHAI SHAH Pass 31 631 633 DRASHTI MOHAN PATEL Pass 32 632 202 GAUTAM MAHIPATBHAI DOBARIYA Pass 33 633 1015 HADIYABANU RAISAEHMAD VHORA Pass 34 634 1016 HANNA MAHEBOOB VHORA Pass 35 635 320 HARIPRIYA RAMAKRISHNAN IYER Pass 36 636 932 HARSHALKUMAR RAJESHBHAI SONAGARA Pass 37 637 639 HEENA VIMAL PATEL Pass Sr. -

Patiala District, Punjab

GLOS3AHY OF CAS'rE NAIVllid RE'fURNED AT TH~ CEI'4SUS O}t' 1951 IN THE DISrRICTS OF PEPSU -_FOREWORD----_ .... ---- ..... __.... At the Oensus of 1951 there was a limited enumeration and tabulation of castes. Under the limited enumeration caste was recorded as returned by the respondent. Several complications arose out of this procedure. Many persons who returned their caste by generic or synonymous Scheduled Caste or tribe names not found in the prescribed lists were left out of the count of Scheduled Castes and Tribes and are-count had to be later ordered in some states. The Backward Classes Commission could not be provided with the 1951 population of individual castes and tribes or their individua~ educational and economic characteristics. 2. If a complete enumeration of castes is ordered at the next census much preliminary study will have to be carried out in order to ensure correct and rational enumeration and tabulation. For that purpose and, in fact, for any systematic enumeration of castes, a glossary of caste names as returned at the 1951 Census would be invaluable. This explains the prepara~ion of t~is glossary. 3. The Glossary has been prepared by running through all the male slips relating to the non-backward classes and the five per cent sample male slips of Backward Classes and sh~uld, therefore, be a complete list of caste names. All caste names as found in the slips have been deliberately included in the Glossary without any attempt at rationalisation. Many of these names are synonymous; some relate to sub-castes or gotras; and some are only generic names. -

VIIA-OBC-1R.Pdf

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI FIRST REPORT COMMITTEE ON WELFARE OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES (2020-21) (SEVENTH ASSEMBLY) SUBJECT: EXAMINING THE ISSUE OF CERTAIN ENTRIES OF THE CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs PERTAINING TO NCT OF DELHI (PRESENTED ON 10.03.2021) ADOPTED BY THE HOUSE ON 11.03.2021 COMMITTEE ON WELFARE OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES Legislative Assembly, Old Secretariat, Delhi – 110054 INDEX Subject Page No. Composition of the Committee (2020-21) iii Preface iv Chapter I Introduction 1 Chapter II Observations and Recommendations of the Committee 5 Chapter III Summary of Recommendations 23 Annexures 26 ii DELHI LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON WELFARE OF OBCs (2020-21) COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE 1. Shri Sahi Ram Chairperson 2. Shri Ajay Kumar Mahawar Member 3. Shri Ajesh Yadav Member 4. Shri Dinesh Mohaniya Member 5. Shri Kartar Singh Tanwar Member 6. Shri Madan Lal Member 7. Shri Mahinder Yadav Member 8. Shri Naresh Yadav Member 9. Smt. Preeti Jitender Tomar Member ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT 1. Shri C. Velmurugan Secretary 2. Shri Sadanand Sah Deputy Secretary 3. Shri Subhash Ranjan Section Officer iii PREFACE 1. I, the Chairperson, Committee on Welfare of Other Backward Classes (2020-21) having been authorised by the Committee to present the Report on their behalf, do present this First Report of the Committee on ‘Examining the issue of certain entries of the Central List of OBCs pertaining to NCT of Delhi’. 2. The Report was considered and adopted by the Committee at their sitting held on 14.01.2021 and presented to the Hon’ble Speaker, Delhi Legislative Assembly on 15.01.2021. -

Scheduled Caste (SC) 81.75 Scheduled Tribe (ST) 70.75 Other Backward Classes (OBC) 81.50 Accordingly, the Following Candidates Are Shortlisted

PHYSICAL MEASUREMENT TESTS & PHYSICAL FITNESS TESTS FOR THE POST OF SECURITY ASSISTANT GRADE-II It has been decided to shortlist candidates, who have secured marks equal or above cut-off marks as shown below in the Combined Preliminary Examination held on 13th April, 2013 for appearing in the Physical Measurement Tests & Physical Fitness Tests for the post of Security Assistant Grade-II. Scheduled Caste (SC) 81.75 Scheduled Tribe (ST) 70.75 Other Backward Classes (OBC) 81.50 Accordingly, the following candidates are shortlisted. SC CANDIDATES S.No Roll No Name Father's Name 1 407583 ANIL KUMAR RAJAN 2 403115 SIDDHARTHA CHHOTEY LAL 3 406046 RAVIKANT BHARATIYA RAMDHAN BHARATIYA 4 405748 PARDEEP KUMAR ABHAY RAM 5 401302 NITIN KUMAR SONKER T N SONKER 6 402713 M GAYATRI SHRI RAMKISHAN 7 405470 VINEET KUMAR DEVANAND 8 403131 SANJAY KUMAR DHANPAT SINGH 9 409692 HEMANT KISHOR NAND KISHOR 10 409957 JOGENDER SINGH RAMPRASAD 11 403448 SUNIL KUMAR AMAR NATH 12 401564 GULSHAN PURAN CHAND 13 405355 ANKIT SAWARIYA HARISH SAWARIYA 14 401621 PRATIBHA MAURYA RAGHUBIR SINGH 15 403337 KIRAN BALA VED PRAKASH 16 402956 VINAY SHER SINGH 17 402805 ANUJ MADHU SUDAN 18 400320 KUMAR GAURAV SONKER SATISH CHANDRA SONKER 19 402054 PRATEEK SAGAR RADHEY SHYAM 20 409137 BHARAT BHUSHAN DHIR SINGH 21 401676 RAJ KUMAR SINGH GHUREY SINGH 22 408765 JITENDER KUMAR VINOD KUMAR 23 408921 DEEPAK RAM PRASAD 24 400659 SHIV MOHAN MAHENDRA KUMAR 25 407287 SONIA BIRAM PRAKASH 26 403577 MAHENDRA KUMAR VERMA DHANI RAM VERMA 27 400460 UPENDRA BHARTI VIJAY SINGH 28 407501 ROHIT VIMAL -

2015-16 Admitted Students

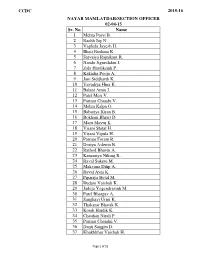

CCDC 2015-16 NAYAB MAMLATDAR/SECTION OFFICER 02-04-15 Sr. No. Name 1 Mehta Porvi B. 2 Rachh Jay N. 3 Vaghela Jayesh H. 4 Bhatt Rushina K. 5 Sarvaiya Rajnikant R. 6 Nandu Jigneshdan J. 7 Zala Hardiksinh P. 8 Kakadia Pooja A. 9 Jani Siddharth K. 10 Vavadiya Hina K. 11 Balani Amin J. 12 Patel Meri V. 13 Parmar Chandu V. 14 Mehta Kalpa O. 15 Babariya Kiran B. 16 Bokhani Bhrart D. 17 Maru Mayur K. 18 Visani Shital H. 19 Visani Vipula H. 20 Parmar Foram R. 21 Doriya Ashwin B. 22 Rathod Bhavin A. 23 Kanzariya Nikunj R. 24 Raval Suketu M. 25 Makvana Dilip A. 26 Raval Avni K. 27 Pipariya Hetal M. 28 Rudani Vaishali K. 29 Jadeja Yogendrasinh M. 30 Patel Bhargav A. 31 Sanghavi Urmi K. 32 Thakarar Bhavik K. 33 Kotak Hardik K. 34 Chauhan Nirali P. 35 Parmar Chandni V. 36 Danti Sangita D. 37 Khakhkhar Vaishali H. Page 1 of 52 CCDC 2015-16 38 Gujarati Krishna R. 39 Madhavi Dharmesh K. 40 Davera Gautam M. 41 Makwana Nirali D. 42 Chotaliya Malay B. 43 Dabhi Manish V 44 Panara Nisha M. 45 Visavadiya Deepak D. 46 Padmani Kaushal M. 47 Vaghasiya Piyush H. 48 Jadeja Shaktisinh S. 49 Gohil Chatur M. 50 Suvagiya Dipali D. 51 Joshi Amit N. 52 Prajapati Nikeeta H. 53 Gohil Renuka R. 54 Variya Nirali A. 55 Vadoliya Nisha G. 56 Joshi Hardik B. 57 Vegda Parth 58 Dervaliya Ashish A. 59 Parmar Niketa M. 60 Vithalapara Moti R. 61 Kunapara Kamlesh K. -

Shri M. P. Shah Commerce College, Jamnagar B

SHRI M. P. SHAH COMMERCE COLLEGE, JAMNAGAR B. COM. Semester : 5 Roll Number Year : 2020-2021 ROLL REG DIV NAME ELECT NO NO 1 A AAYADI BHAVANABEN NATHUBHAI AC S180303 2 A AJUDIA BHAKTI JAGDISHCHANDRA AC S190476 3 A AJUDIYA BANSIBEN SANJAYBHAI AC S180398 4 A AMETHIYA SHIVANI JENTIBHAI AC S180460 5 A ANADKAT MOSAMI DHARMENDRABHAI AC S180030 6 A ANDANI GRISHMA KAMLESHBHAI AC S180138 7 A ARANDIYA AURANGZEB BASIRBHAI AC S180118 7 A ASVALA NENSI SUBHASHBHAI AC S180188 9 A BARAD MIHIR KETAN AC S180499 10 A BATHVAR DIVYABEN JIVRAJBHAI AC S180300 11 A BATHVAR HARDIKBHAI HAJABHAI AC S180363 12 A BERA BHAVIN DHARNANTBHAI AC S180248 13 A BETAI SOHAGI RASHIK AC S180447 14 A BHADRA DIVYA BHARATBHAI AC S180073 15 A BHADRA MAITRI AJAYBHAI AC S180037 16 A BHAKTANI MAHEK SATYAPAL AC S180020 17 A BHANDERI POOJA ANILBHAI AC S180060 18 A BHARMAL SAKINA JUZERBHAI AC S180017 19 A BHARVADIYA JITENDRA MALDEBHAI AC S180141 20 A BHATIYA GOVIND VEJANANDBHAI AC S180250 21 A BHATT NIYATI JAYESHBHAI AC S180487 22 A BHATT RAJ HARISHBHAI AC S180035 23 A BHATT RIDDHIBEN MUKESHBHAI AC S180006 24 A BHATTI RISHI NILESH AC S180496 25 A BHAYANI KRISHA HARESH AC S180062 26 A BHIMBHA RUSHITA JAGABHAI AC S180115 27 A BLOCH MAHEK SAJIDBHAI AC S180100 28 A BORICHA BHAGIRATH UMEDBHAI AC S180176 29 A BORICHA KINJAL JITENDRABHAI AC S180244 30 A BUHECHA DHRUTIBEN DINESHBHAI AC S180153 31 A BUHECHA HINAL RASIKBHAI AC S180114 32 A BUSA JANKI ARVINDBHAI AC S180080 33 A CHACHAPARA MIRAL DHIRUBHAI AC S180130 34 A CHAIRABHUJ JANVIBEN RAMESHBHAI AC S180218 35 A CHAKKA RUKAIYA ALIHUSSAIN AC S180039 36 A CHANDARIYA ISHA PUNILBHAI AC S180376 37 A CHANDRAVADIYA LAKHAMAN VARAVABHAI AC S180413 38 A CHANDRESHA BHAKTI ANILBHAI AC S180215 39 A CHAUDHARI CHIRAG SURESHBHAI AC S180359 Page : 1 of 12 SHRI M. -

Cc-5:History of India(Ce 750-1206) I

CC-5:HISTORY OF INDIA(CE 750-1206) I. STUDYING EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIA RISE OF RAJPUTS AND THE NATURE OF THE STATE Where and how the Rajputs originated remains a doubt. The four (Agni- kula) clans established their power in western India and over parts of central India and Rajasthan. The period from1000-1200 CE saw rapid changes both in west and central Asia and in North India. With the break up of the Pratihara kingdom a number of Rajput states came into existence in northern India. There are many theories regarding the origin of the Rajput. The bards of the 14th century mentions ‘Rajput’ as a tribe comprising thirty-six clans of which the Pratiharas, Paramaras, the Chauhans, the Solankis, the Gahadavalas, the Tomaras etc played an important role in the history of the period. The Rajputs claimed to be the real descendants of the Kshatriyas of the Vedic times. Their king traced their ancestry either to the Sun family(Suryavansha), or the Moon family(Chandravanshi).But the Pratiharas, Paramaras, the Chauhans, the Solankis traced their pedigree from the Fire family(Agni- kula).The Pratihara clan had further two branches.One branch ruled in the Jodhpuar state and was known as the Gurjaras. while the other branch founded a kingdom in Malwa. The four (Agni-kula) clans established their power in western India and over parts of central India and Rajasthan. Gahadavalas of Kanauj-Following the fall of the Pratiharas,the Gahadavalas were able to establish themselves in the throne of Kanauj in the third quater of the 11th century CE. -

Chapter: Iii Origin, History and Introduction of the Rajputs (Kshatriyas)

CHAPTER: III ORIGIN, HISTORY AND INTRODUCTION OF THE RAJPUTS (KSHATRIYAS) Sr.No. Details Page No. 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Origin and History of the Rajputs (Kshatriyas) 3.3 The Origin and History of Karadiya Rajputs 3.4 Peculiarities of Karadiya Rajputs 3.5 Folk life of Karadiya Rajputs 3.6 Conclusion References 210 CHAPTER: III ORIGIN, HISTORY AND INTRODUCTION OF THE RAJPUTS (KSHATRIYAS) Sr.No. Details PageNo. 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Origin and History of the Rajputs (Kshatriyas) 3.2.1 Preface 3.2.2 The Aryan Culture 3.2.3 The Rise of Rajputs (Kshatriyas) 3.2.4 Varna system and Rajputs 3.2.5 A historical view 3.2.6 The Rajput period 3.2.7 Meaning of the term ‘Rajput’ 3.2.8 The origin of the alternative terms of ‘Kshatriya’ 3.2.8.1 Rajput 3.2.8.2 Thakur 3.2.8.3 Darbar 3.2.8.4 Garasiya 3.2.9 Different Rajput family lines in Gujarat 3.2.10 Rajput Ruling family lines 3.2.11 Mythological origins 3.2.12 The Chandravanshi (born from the Moon) and the Suryavanshi (born from the Sun) 3.2.13 Family lines born of fire 3.2.14 Famous Rajput family lines 3.2.15 Famous royal family lines 3.2.16 Rajput states in the British Rule 3.2.17 The family line from Narayan (Lord Vishnu) to Ramchandra as mentioned in the Purana 3.2.18 The family lines from Shri Ramchandra to Supit and Kanaksen 211 3.2.19 Table showing a list of Rajput family lines 3.2.20 36 royal families and the Rajput family trees 3.2.20.1 Names of 36 royal family trees 3.2.20.2 36 Royal family lines 3.2.20.3 36 Rajput family lines 3.2.20.4 36 Branches of the Rajputs as described by Poet Chand 3.2.20.5